Private William H. Stanley, which was what he called himself then, marched forward in the hour before dawn on April 6, 1862, as part of the Dixie Grays, a volunteer company in the 6th Arkansas Infantry. He reached down to the ground to scoop up some violets and stuck them in his cap, the way his friend Henry Parker had done moments before. Parker told him that if the Yankees saw flowers in their caps, maybe they would not try to kill them. The unit was in Tennessee, near a church with a Biblical name: Shiloh.

As the sky brightened a bit, the officers shouted for the men to fix bayonets and move out on the double quick. Stanley and the others charged, yelling and shooting into a Union camp of tents and half-dressed men just waking up. Bullets flew and soldiers on both sides cried out in shock and pain. Stanley saw a bullet rip apart the face of the man beside him. On the other side he heard young Parker scream. “Oh, stop, please stop a bit. I have been hurt and can’t move.” The boy with the flowers in his cap was staring at his bloody, mangled foot.rivate William H. Stanley, which was what he called himself then, marched forward in the hour before dawn on April 6, 1862, as part of the Dixie Grays, a volunteer company in the 6th Arkansas Infantry. He reached down to the ground to scoop up some violets and stuck them in his cap, the way his friend Henry Parker had done moments before. Parker told him that if the Yankees saw flowers in their caps, maybe they would not try to kill them. The unit was in Tennessee, near a church with a Biblical name: Shiloh.

“I cannot forget that half-mile square of woodland, lighted brightly by the sun, and littered by the forms of about a thousand dead and wounded men, and by horses and military equipments…”

The Rebel troops ran forward, chasing the Yankees as they retreated. A stray shot hit the clasp of Stanley’s belt and knocked him down. He claimed to be too stunned to stay in the fight, but had enough presence of mind to crawl behind a tree. Settling down, he searched his haversack for something to eat.

After half an hour he roused himself and walked through the battlefield, surveying all the dead young men. “I cannot forget that half-mile square of woodland, lighted brightly by the sun, and littered by the forms of about a thousand dead and wounded men, and by horses and military equipments,” he later wrote. “It was the first Field of Glory that I had ever seen in my life and the first time that Glory sickened me with all its repulsive aspects, and made me suspect that it was all a glittering lie.”

As the Rebels made another attack the next morning, Stanley found himself confronting six Union soldiers with bayonets aimed at him: “I dropped my weapon incontinently. Two men sprang at my collar, and marched me, unresisting, into the ranks of the terrible Yankees.”

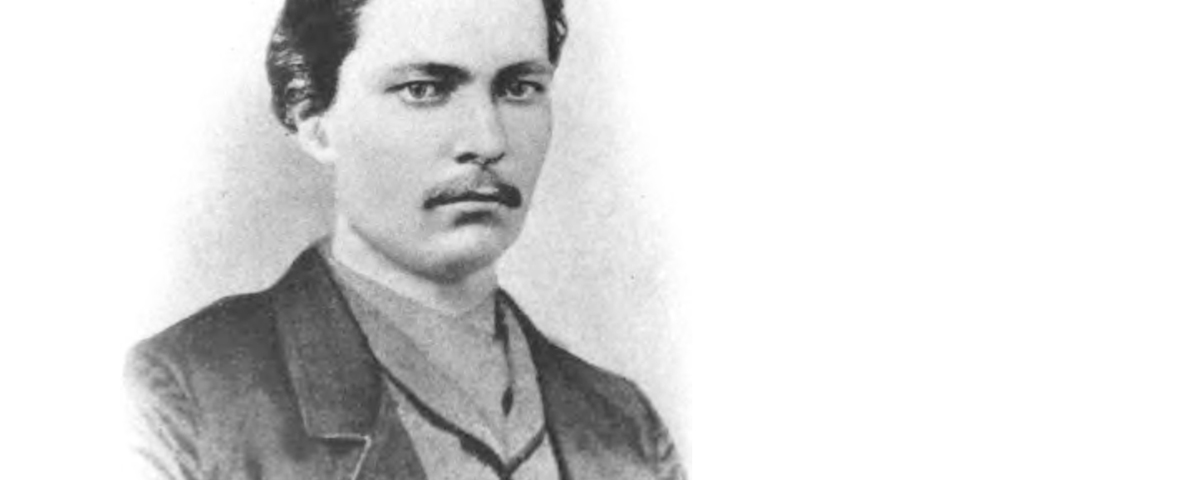

William Stanley became better known as Henry Morton Stanley, but that was not his real name, either. When he was born 20 years earlier in the town of Denbigh, Wales, church records listed him as “John Rowlands—Bastard.” His mother was a 19-year-old unmarried housemaid who later had three other children, each by a different father. John Rowlands’ father might have been the village drunk; neither he nor the boy’s mother showed any interest in John’s welfare.

Nor did anyone else. His aged grandfather gave him a home for a while but was physically abusive. When the old man died, other relatives paid an elderly couple to take him in. Eventually John ended up in a workhouse with 70 other destitute, abandoned children where, he said, he learned how unimportant tears were. Crying only led to more severe beatings. “Tyranny of the grossest kind lashed and scowled at us every waking hour,” he recalled later in life. “Day after day, little wretches would be flung down on the stone floor in writhing heaps or stood with blinking eyes and humped backs to receive the shock of the ebony ruler.” A childhood out of a Charles Dickens story, he thought.

John remained at the workhouse until age 15; he sought help from relatives but was always turned away. At 16, he made his way to the port city of Liverpool and signed on to join the crew of an American cargo ship that reached New Orleans seven weeks later. On his first night in the United States, he claimed, one of the other sailors took the boy to a brothel where, as he put it, the girls “proceeded to take liberties with my person.”

His situation quickly improved; he was hired as a clerk the following day. He showed that he was intelligent and quick, and he could read and write—advanced skills at that time. Through his work he claimed to have met Henry Hope Stanley, a wealthy cotton broker who took Rowlands into his business, taught him manners and etiquette and gave him time off to study the great literary classics. Stanley sent him off to Cypress Bend, Ark., to learn the retail trade by working in a country store. Some historians have suggested Stanley sent him away because he had become too dependent, trying too hard to ingratiate himself with Stanley’s family. And once again, the boy found himself rejected and on his own.

While at least one biographer has questioned this relationship, it is how Rowlands chose to tell his story. He adopted Stanley’s name as his own, adding “Morton” as his middle name sometime later.

By 1861, the Civil War was brewing and patriotism was running high, but not for a young man from Wales. It was not his war. His attention was focused on a young lady in town who seemed quite friendly to a mere store clerk. He had no interest in the Dixie Grays, the local militia then being formed. The men drilled regularly and boasted how they would beat the Yankees in no more than a week or two. In the eyes of the town, they were heroes.

Before long, Stanley was the only young man not in uniform, the only one not spouting patriotic slogans and eager to go off and fight. He would have been content to stay out of it had he not received a package containing a chemise and a petticoat, symbols of cowardice, perhaps sent by the young woman he was interested in. “I hastily hid it from view,” Stanley wrote, “and retired to the back room, that my burning cheeks might not betray me to some onlooker.” He joined up the next day; an act he later admitted was “a grave blunder.”

After their capture at Shiloh, Stanley and other Confederate prisoners were taken aboard a steamer to St. Louis and by train from there to a camp outside Chicago. Camp Douglas, a Union prisoner-of-war camp, was a 70-acre hellhole surrounded by a 12-foot wall of wooden planks. The property flooded in heavy rain and lacked adequate sanitary and medical facilities. It housed some 8,000 prisoners. The death rate was above 20 percent, with more than 200 dying every week from dysentery and typhoid. Bodies were rolled up in blankets and piled atop one another. Stanley concluded that they all were “simply doomed.”

He endured for six weeks until June 4, 1862, when he took advantage of the offer made to Confederate prisoners to swear allegiance to the Union Army and leave Camp Douglas. Some 5,600 men agreed to join the Federals, becoming what was called “Galvanized Yankees.” Thus, the private now known as Henry Stanley set out in his new blue uniform. But he got only as far as Harpers Ferry, Va., before he had to be hospitalized with dysentery and fever. His regiment departed a few days later, leaving him with orders to rejoin the outfit when he recovered. He later wrote that he was given a discharge for health reasons, but that was a lie. The regiment was stationed nearby and when he failed to report for duty, he was officially listed as a deserter on August 31, 1862.

By then, Stanley was several miles away from the hospital, having spent 12 days on the road. “My condition at this time was as low as it would be possible to reduce a human being to,” he remembered. “I had not a penny in my pocket. I knew not where to go; the seeds of disease were still in me and I could not walk three hundred yards without stopping to gasp for breath.”

But he reached Hagerstown, Md., where a farmer came to the rescue of the young man in a Union uniform. Stanley spent several days in bed, apparently in a coma, and when he woke up, he found that his body had been bathed and he was dressed in clean clothes. The farmer and his wife, Mr. and Mrs. Ezra Baker, nursed him back to health, and by July he felt strong enough to help them bring in their harvest. The Bakers paid for a train ticket to Baltimore, the nearest port. John Rowlands, alias Henry Morton Stanley, had decided to go home.

He signed on as a deckhand on a ship bound for Liverpool. He arrived in October 1863, looking like what he had become: a penniless, disheveled wanderer who had not known any success. He planned to visit his mother and the man she had married, but she was no more welcoming than ever. She was ashamed of her son and embarrassed by his appearance.

“With what pride I knocked at the door, buoyed up by the hope of being able to show what manliness I had acquired,” Stanley wrote. “I had arranged my story to please one who would at last, I hoped, prove an affectionate mother! But I found no affection, and I never again sought for, or expected, what I discovered had never existed. I was told that ‘I was a disgrace to them in the eye of their neighbors and they desired me to leave as speedily as possible.’” After having traveled 3,000 miles, the last 15 on foot, Stanley walked back to Liverpool and signed aboard another ship. He never returned to Wales.

Later that month he was in New York City, where he got a job as a clerk for a notary public. He kept that job for eight months until, for reasons never made clear, he joined the Union Navy. This time he used the name Henry Stanley again, but changed his date and birthplace on the enlistment form. He did not want to risk being identified as an Army deserter.

As a ship’s clerk aboard the steam frigate USS Minnesota, he worked closely with officers and kept the ship’s daily log as it sailed south. Stanley watched the action as Minnesota’s guns pounded Fort Fisher, off the port of Wilmington, N.C., a frequent destination for blockade runners bringing desperately needed supplies to the Confederacy.

It was tedious and dull duty, mostly anchored off the coast, leaving Stanley with considerable time to indulge in daydreams. He concocted stories in which he was a hero in battle. In one story he recorded, he imagined he swam 500 yards during an attack on Fort Fisher, tied a rope to a Rebel ship and presented it as a gift to the admiral, for which he was made an officer. He did not tell anyone about his fantasies. In fact, he said very little.

“Stanley hardly spoke to anybody,” said shipmate Lewis Noe. “He would sit by himself, reading whenever he had the chance. But when he did emerge from his book, he displayed a pleasing address and an air of confidence. He talked well, and although he was just a ship’s clerk, he adopted the manner of an officer.”

Writing the daily log was neither difficult nor time-consuming and Stanley took advantage of that by writing colorful and more than a bit exaggerated accounts of the bombardment of the Confederate fort. He sent them off to several newspapers that bought and published them. He was on his way to a new career as a paid journalist. He soon switched his focus from imagined adventures to the real-life experiences he could have and the exotic places he could visit and write about, starting with the American West. Then there was all of Europe and the dark, exotic continent of Africa, most of which was unexplored by any white man.

If he were free to undertake these trips, he could advance his career from cranking out stories about the war to writing books like his favorite author, explorer and travel writer Richard Francis Burton. These thoughts fueled his growing desire to become rich and famous, which would never happen as long as he was a sailor aboard the Minnesota, writing the ship’s daily logs.

He decided to leave the Navy and head out West. He talked Noe, 15, into joining him. While the ship docked on February 10, 1865, for repairs at the naval base in Portsmouth, N.H., Stanley and Noe disappeared. Armed with passes Stanley had forged granting them both leave, they took off their uniforms as soon as they were out of sight and left in the civilian clothes they wore underneath. Noe soon changed his mind, however, and, afraid of being found to be a deserter, he joined the Army under an assumed name.

Stanley went west on his own, to the gold fields of Colorado. But he did not find any gold. He roamed restlessly from place to place, finding temporary work as a freelance journalist, bookkeeper or day laborer. He finally found steady employment in 1867 as a reporter for the St. Louis Democrat, for $15 a week. His first assignment was to accompany an Army expedition led by Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock against Indians. The expedition was ultimately a failure; instead of pacifying the Indians and getting them to agree to new peace treaty terms, Hancock’s arrogant leadership only fomented greater Indian troubles. But that was good for Stanley, because he got more newspaper articles, which increased his visibility and reputation as a good journalist who produced solid reports. He also met many fascinating people, including Wild Bill Hickok and George Custer.

Among those who noticed his work was James Gordon Bennett, the influential editor of the New York Herald. In 1871, Bennett financed Stanley’s trip to Africa for a really big story: finding out what had happened to famous British missionary and explorer David Livingstone, who had not been heard from in two years.

After a grueling and dangerous eight-month trek through the jungles, Stanley finally found him on November 10, 1871, at a village on the shore of Lake Tanganyika. It was then, Stanley claimed, that he uttered the words that made him famous: “Dr. Livingstone, I presume.” o

Psychologist Duane Schultz has written more than a dozen military history books and articles. His latest book is Evans Carlson, Marine Raider: The Man Who Commanded America’s First Special Forces (Westholme, 2014). This article was originally published in the September 2015 issue of America’s Civil War.