After a devastating Royal Navy loss, military authorities felt duty bound to keep a careful eye on a famed Scottish mystic.

The afternoon of November 25, 1941, had been relatively quiet for the 1,350 men aboard the battleship HMS Barham. Along with 12 other ships from the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean Fleet, Barham was sailing off the coast of Egypt, providing gun cover for cruisers on the hunt for Axis ships en route to North Africa. The fleet thought they were alone in the area’s waters.

Crewmember Douglas Ralphs went below for a cup of tea.

“I had just lifted the cup to my lips when the first ‘tin fish’ hit,” Ralphs recalled. “There was an enormous explosion, followed by a deathly silence, and an acrid smell of super-heated steam and the stench of cordite.”

A German U-boat torpedo had struck the battleship; two more quickly followed. The 643-foot Barham rolled to its port side. Crewmembers on the convoy’s other battleships, the Valiant and the Queen Elizabeth, watched as columns of smoke and water sprang from the ship’s wounds. They could do nothing to help.

Several of the boat’s four-inch magazines were on fire. The blaze spread, moving to the main 15-inch magazines. “There followed a big explosion amidships, from which belched black and brown smoke intermingled with flames,” Valiant’s commanding officer, Captain C. E. Morgan, later recalled. Wreckage peppered the water.

Four minutes and 35 seconds after the first torpedo struck the Barham, the battleship disappeared from sight. Though 488 men were saved, 862 others would never return home.

The day’s only saving grace: British intelligence knew that the German navy and high command were unaware of Barham’s fate. The British wanted to keep it that way. With German bombs raining down on England, including a raid earlier in 1941 on Portsmouth—home of His Majesty’s Naval Base—that killed 171, the British people were already reeling from loss. Worried that news of a major German victory over the Royal Navy would sink military and civilian morale even more, the Admiralty clamped down on reports about the Barham. The authorities delayed telling family members the grim news for several weeks, going to the length of mailing them Christmas and New Year’s messages, seemingly from Barham sailors, including those who had died. Once the Admiralty did notify the families, they asked them to keep the deaths of their loved ones a close secret. Official acknowledgment of the sinking would not be made public until January 27, 1942.

Despite the official secrecy, word of the disaster leaked out from a most unusual source: a famous medium named Helen Duncan spoke of the Barham’s end during a séance in Portsmouth. Duncan—a sturdy woman with bluntly cropped hair who wasn’t afraid to use salty language now and again—had already captured the attention of the military earlier in the year when she reported another loss, that of battleship HMS Hood. Eyes now again turned to Duncan, who seemed to be making a habit of knowing things she shouldn’t.

BORN IN CALLANDER, SCOTLAND, in 1897, Helen Duncan—then Victoria Helen McRae MacFarlane—was not your average child. The fourth of eight children, Helen claimed by age seven that spirits of the dead visited her. Clairvoyants were no strangers to Helen’s family; both of her parents had female relatives who professed similar powers. Though her parents didn’t discourage Helen from talking about her visions, they urged her not to discuss them outside the family, reasoning that there were people who would take advantage of such a child. But Helen was no pushover, and her independent streak could not be contained. Her family gave the strong-willed and boisterous child a nickname that would stick with her forever: “Hellish Nell.”

At 16, Helen’s life took a turn that would strip some of the fire from Hellish Nell. She became pregnant out of wedlock and her parents turned their backs on her. They sent her away, disgraced. Helen moved to Dundee, on the east coast of Scotland. After a stint in a sanatorium for tuberculosis, she took a job at the Dundee Royal Infirmary. In 1915, she had her first child, a girl.

The next year, Helen met and married Henry Duncan, a coworker’s brother. A local man, Henry had been dismissed from the army for rheumatic fever. That misfortune was one of many Henry suffered during his life—and that would continue through the early years of the Duncans’ marriage.

Illness dominated Helen and Henry’s lives, often forcing their hand when it came to taking or quitting jobs. Although she was often sick, Helen went on to have six children.

Money problems festered for the young, growing family. After a furniture company that Henry started had failed, Helen added a position at a bleach factory to an ever-growing list of hard physical jobs. Then Henry had a heart attack. His working days were done, and Helen became the sole breadwinner for the family of eight. But Henry, who also had spiritualist leanings—though only as an interest, not as a skill set—realized Helen’s visions could be a way out of their money problems. Still reporting to the bleach factory during the day, in 1926 Helen began the work that would make her both famous and infamous: holding séances.

EARLY 20th-CENTURY SPIRITUALISTS and their followers believed that spirits of the dead could be called forth to communicate with the living. Mediums like Helen offered people the comfort they needed, the messages they craved from loved ones. Helen’s popularity grew; through the interwar years she and Henry traveled throughout the country, hosting séances in spiritualist churches and private homes. By the 1940s, séances were a widespread practice—the Royal Navy approved of their practice aboard ships and in 1941 declared spiritualism an official religion. It’s estimated that over the course of World War II up to 50,000 séance circles took place throughout Britain.

Much of Helen’s fame came from the theatrical nature of her séances. Before each performance began, Henry would invite several female audience members to a back room. There, Helen stripped in front of the women, twirling on their demand, to prove she wasn’t hiding anything on her body.

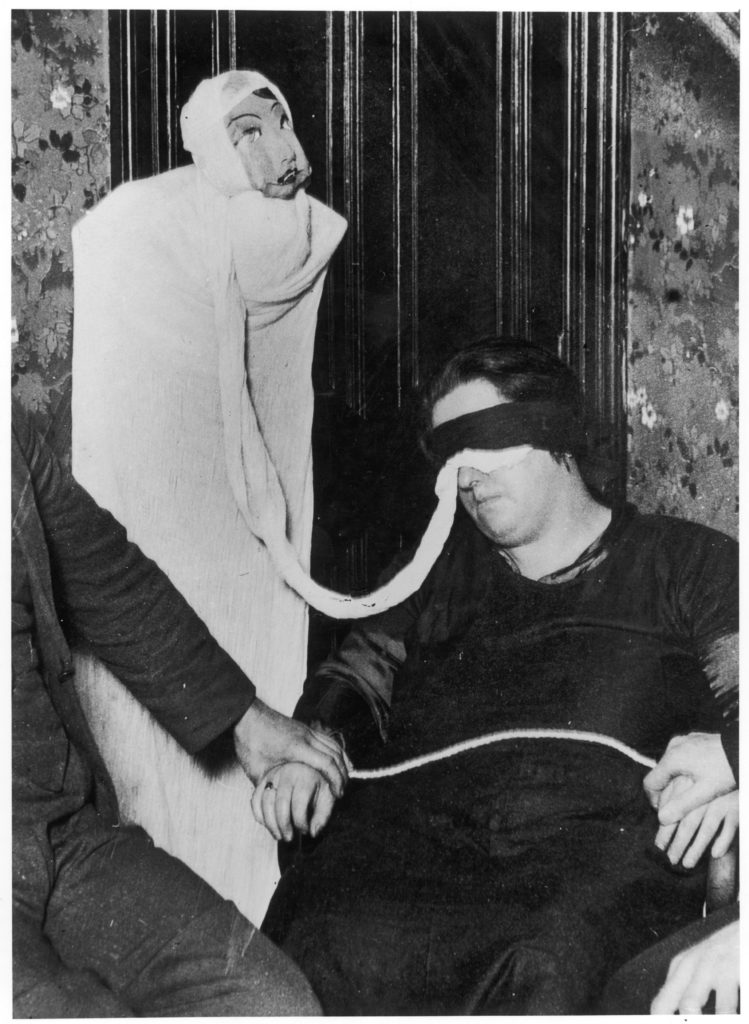

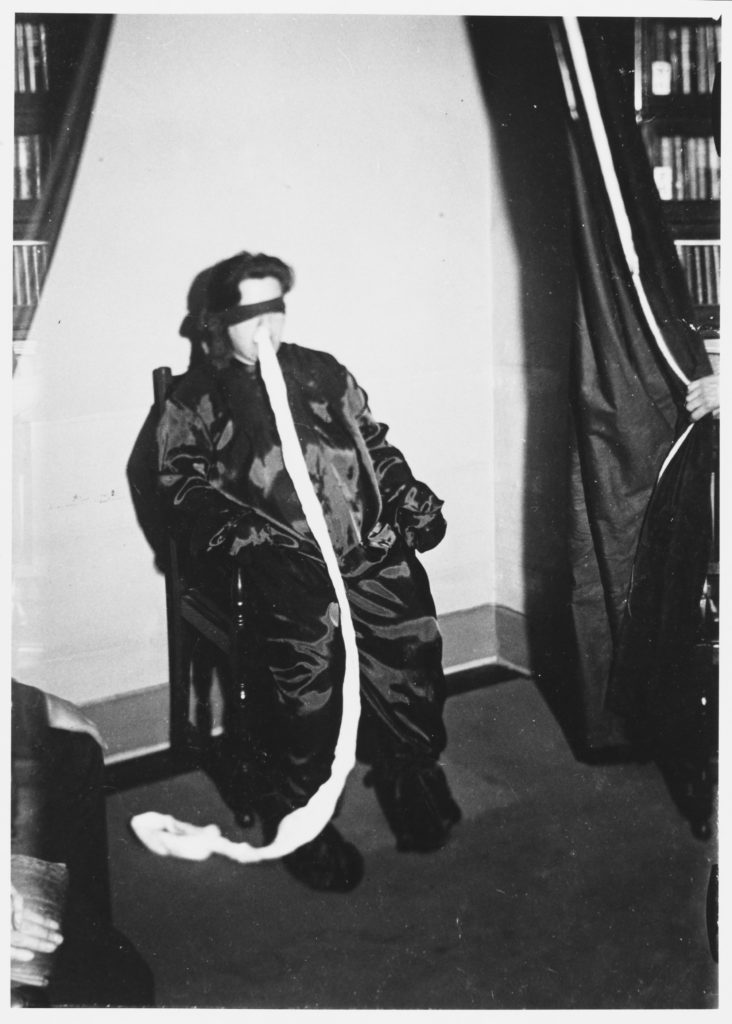

Then, dressed in black silk, she would sit in a wooden cabinet Henry had fashioned, which he claimed helped harness her power. With a red light casting a glow on her in the otherwise dim room, Helen would enter a trance state. Eventually, a gauzy white substance spilled from her mouth, announcing the arrival of a spirit, and an airy white figure would float into view and move around her. These were Helen’s “spirit guides,” who spoke through the medium and helped her summon forth the dearly departed. The voices of Helen’s spirit guides were softer, more approachable, and easier to understand than the medium’s natural, provincial, Callander-accented speech. One of the spirit guides was even a child.

In 1928, Helen agreed to let photographer Harvey Metcalfe use flash photography to catch the white substance—“ectoplasm”—as it emerged from her body. That must have given her pause, but she suspected that people’s need for her services would inoculate her against any inconvenient truths skeptics could find, and she was right. Though Metcalfe discovered her true skill was the ability to regurgitate muslin she had swallowed previously, her séances continued to fill up. Even after distrustful audience members grabbed at the floating spirits she claimed to summon and exposed them as nothing but papier-mâché heads with cloth bodies, she remained popular. In 1931, Helen even allowed the London Spiritualist Alliance to examine her ectoplasm, which showed that she’d added egg whites to the muslin to make it slimy. None of these revelations dimmed her star: her true believers, those who had found comfort in supposed visits from dead relatives, stuck by her and stood up for her publicly.

Helen’s séances probably would have remained nothing but a thorn to her skeptics and a comfort or curiosity to audience members had not her two 1941 demonstrations in Portsmouth focused military authorities’ attention on the mystic.

In late May of that year, a Brigadier Roy C. Firebrace attended one of Helen’s séances. Helen, speaking in the voice of “Albert,” one of her regular spirit guides, told those in attendance that a British battleship had just been sunk. The sinking was news to the brigadier. Later that evening he checked with members of the Royal Navy, but nobody had heard anything about a ship going down. The next morning Firebrace found out that HMS Hood had sunk the day before during the Battle of Denmark Strait.

Months later, at a séance just after the Barham had sunk but before it was public knowledge, Helen’s spirit guide told the audience he was in contact with a dead sailor. The sailor had a message for a woman in the audience: he was her son and he had died in a sinking. The grief-stricken woman, unaware that her son had been killed aboard the Barham, contacted the Admiralty. Rumors spread throughout Portsmouth, defying the navy’s attempt to control the story.

IT WASN’T UNTIL JANUARY 1944—more than two years later—that the authorities decided it was time to silence the medium. They had been keeping watch over Helen, at times planting police in the séance audiences. With planning for D-Day in full swing, there was no room for more rumors—not even from a spiritualist who worked in egg whites and muslin.

On January 19, 1944, the police raided Helen’s séance. They arrested and charged her under the Vagrancy Act of 1824, a catch-all, preemptive crime control measure. The medium was so famous by then that BBC Radio broke away from news of the Russian advance on the Eastern Front to report on her arrest.

The crime was just a misdemeanor, but it was clear the authorities wanted to keep Helen from working. After her arrest, the police went so far as to ask the court to have her remanded to jail, an unusual request considering the minor charge. The judge agreed. Helen spent four days in one of the most wretched jails in the Portsmouth area, but her real challenge was yet to come.

Worried that the Vagrancy Act wouldn’t do the job of putting her out of business, the authorities reached into the past for a charge that would lead to a trial. They turned to the Witchcraft Act of 1735, which made it illegal to claim to possess magical powers.

The raid on the séance hadn’t produced any of the physical evidence the authorities needed to prosecute Helen—fellow spiritualists most likely had whisked away the ectoplasm and other ghostly materials before the police could grab them. Without any damning material evidence against her to refute, Helen’s defense focused on demonstrating that her mystical talents were real. During the trial, the defense produced 49 witnesses, most of whom attested that Helen had indeed brought forth the spirits of family and friends.

Chief Constable Arthur West, prosecutor for the Crown, declared, “She attempted and succeeded in deluding confirmed believers in Spiritualism. She has tricked, defrauded, and preyed upon the minds of a certain credulous section of the public.” The prosecution put up only five witnesses, but they also introduced the photographs taken nearly two decades earlier that proved the ectoplasm was fake.

The judge, Sir Gerald Dodson, displayed clear amusement at various points in the trial. But West, who had long wanted to take Hellish Nell down, reminded the judge of the seriousness of the charge when he asserted, “In 1941, Mrs. Duncan transgressed the security laws,” adding that “she is an unmitigated humbug and pest.”

When the seven-day trial ended, the judge ruled that Helen had exploited those who had come to her for help. “The sentence of the Court upon her,” he said, “is that she be imprisoned for nine months” in a London prison. With that, Helen fainted.

Hellish Nell spent just six months in prison and promised to stop holding séances after her release. She was unable to keep that promise. Helen started up her work again and, in 1956, the police arrested her during another raid—but they were forced to immediately release her when their search again failed to recover any material evidence. It was the last bit of good news in Helen Duncan’s life. Just six weeks later, at the age of 59, Hellish Nell died a natural death.

TO THIS DAY, nobody is certain how Helen learned of the Barham’s sinking. Estimates show that between military personnel and the families of the sailors on board, plus the sailors who survived the sinking, up to 20,000 people may have had knowledge of the attack before the Royal Navy officially acknowledged it. In a military town like Portsmouth, keeping such a huge secret would be nearly impossible. In addition, there are several conflicting accounts of the infamous 1941 séance: Some in attendance said Helen had mentioned the Barham by name, while others present said she had not named any particular ship. Still others believed Helen coaxed the ship’s name from the unsuspecting mother.

No matter. Even today, Helen has supporters and grandchildren who are actively working to clear her name, claiming she was a true mystic who was wrongfully convicted. Hellish Nell’s spirit would be proud. ✯