For many Southern civilians, Union occupation was sheer cruelty

“We had not slept long when our old faithful watchdog Carlo awakened us by jumping against the door.” That was how Bettie Blackmore recounted in her diary the terrifying night of February 11, 1863, when Yankee troops in occupied Murfreesboro, Tenn., had set fire to and destroyed Bromfield Lewis Ridley’s majestic plantation home, Fairmont. Ridley, a chancellor of the court in Murfreesboro and one of Middle Tennessee’s wealthiest slave owners, had built Fairmont on 3,000 prime acres along the Stones River, in the nearby town of Jefferson. When the Federals established a military government in the region in early 1863, he was removed from office—along with just about every other local public official—and fled to Georgia with one of his daughters to avoid being jailed.

Four of Ridley’s sons had enlisted in the Confederate Army. Left behind at Fairmont were his wife, Rebecca; his daughter, Mary Elizabeth “Bettie” Ridley Blackmore, whose husband William was serving in the 20th Tennessee Infantry; three female house guests; and at least 25 slaves. In her diary Bettie described herself as “helpless,” too ill to travel because of tuberculosis. She would write that after being awakened by their faithful dog, she heard her mother scream, “Great God! The house is on fire.” Rebecca and their guests ran for their lives; Henry, one of their slaves, carried Bettie to safety.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]We had not slept long when our old faithful watchdog Carlo awakened us by jumping against the door.”[/quote]

The Ridleys had been brought to their knees by the Yankees that night, but they were not alone. Civilians had lived in terror since April 1862, when the Union 23rd Brigade, Army of the Ohio, under Colonel William W. Duffield, occupied Murfreesboro—a key railroad town 35 miles southeast of Nashville, with strategic command of roads and rails to Knoxville and Chattanooga.

During the occupation, the beautiful Fairmont became a safe haven for Southern troops, and probably for spies as well. It was even prominently marked on a captured map that had belonged to Confederate commander John Pegram, so the place had been watched by Union troops for months, and marauding Yankees had stripped it of most things of value even before it was torched that February night.

In March 1862, Union officials removed Tennessee Governor Isham Harris, who had declared secession for his state, and replaced him with Unionist Andrew Johnson as military governor. Federal forces moved steadily across the state, instituting martial law, which often proved to heighten the threat to civilians. Several communities in other Southern states—notably Kentucky, Missouri, and the Boston Mountains of Arkansas—faced a similar fate.

A Nashville reporter for The New York Freeman’s Journal wrote of “indiscriminate plundering” in Middle Tennessee “with the full knowledge of military authorities.” Bettie penned in her journal: “Crowds of insolent Yankees came daily to our house for forage, chickens, horses, meat, and everything else.” The day after burning Fairmont they came back, taking the last of the family’s mules and food. As much as Bettie and her mother suffered, 25 frightened slaves were also still on the place with little to eat and nowhere to go.

Troops took over prime plantations, such as Oaklands, home of Lewis Maney, where Duffield made his headquarters with the 9th Michigan Infantry. For two months, the 7th Pennsylvania Cavalry conducted daily patrols of every road leading from Murfreesboro. Hatred and fear grew as the undisciplined soldiers spewed threats that turned from idle talk to brutal attacks, and insisted that the locals feed them and their mounts. Still, civilian resistance continued. Troops were harassed and even attacked by guerrillas. Families of Confederate soldiers supplied them with warm socks and blankets.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Confederate-loyal civilians were placed in confinement under heavy guard with threats of hasty execution[/quote]

Local resident William H. King later wrote in Confederate Veteran magazine that Harris, even in exile, continued to consider himself the state’s duly elected governor and commissioned James H. Bond of Wilson County, north of Murfreesboro, to go within the Federal lines and raise a company for the Confederate 7th Tennessee Infantry. By July 7, 1862, he had about 20 men eager to rid the neighborhood of the Union patrols. They waited on the Woodbury Road to capture a seven-man patrol at a river crossing. When Bond commanded the Yankees to surrender, they drew their pistols and fired wildly, so the Confederate recruits returned accurate fire, killing five and wounding the other two.

“By noon,” King wrote, “a thousand [Union] men, fully armed, were on the warpath. With no idea who made the attack, federal troops made mass arrests of Confederate-loyal civilians, some suspected spies, some with sons in Southern service, and some believed to have furnished supplies to the south.” King said they were “placed in confinement under heavy guard and with threats of hasty execution, which reached the ears of loved ones.”

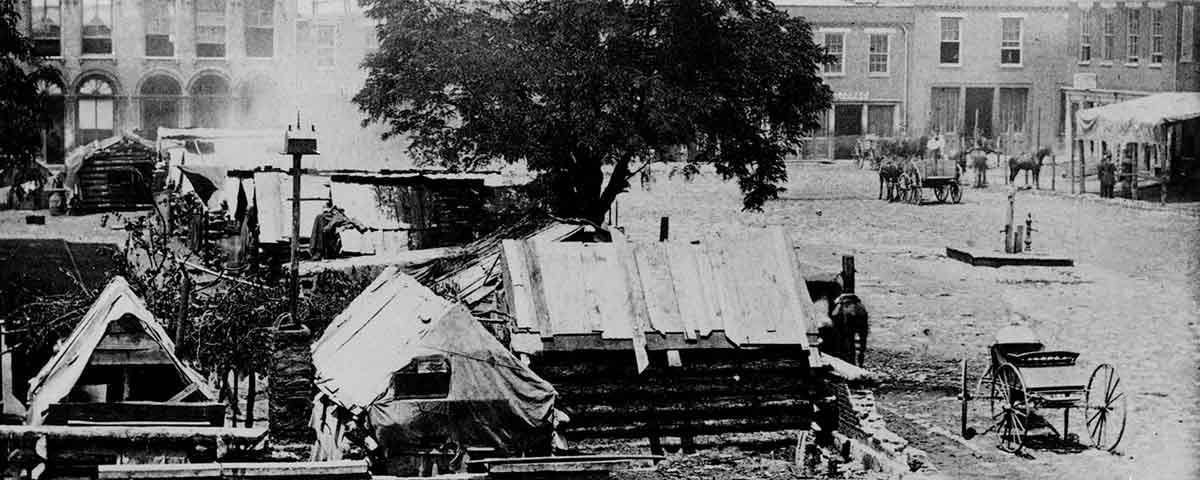

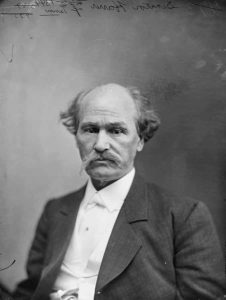

Coincidentally, the day of the arrests, Thomas Turpin Crittenden, a lawyer who had been a brigadier general since April, arrived to command the Federal garrison. He was furious about the July 7 attack, and announced that six civilian prisoners would be executed the following Monday, then ordered that for every soldier shot and killed from that point on, he would execute 100 citizens. That night he retired to the Spence Hotel, trusting in his troops camped outside in the town square. At least 150 civilians were being held on the upper floor of the courthouse and in the local jail, with some reports putting the total at 300. They included physician Lunsford Black, W.R. Owen, a Primitive Baptist preacher, and Bettie’s 17-year-old brother Charley, charged as a guerrilla.

Fortunately for the condemned, Confederate Brig. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest was approaching from Chattanooga to capture the Yankee stronghold at Murfreesboro. Arriving at Woodbury, 19 miles to the east, he was surrounded in the street by terrified women telling him that the Federals had arrested their men, were allowing no visitors, and planned to hang some of them on Monday morning, July 14.

Forrest moved quickly to surprise the occupying army before dawn on July 13. His cavalrymen rode near the Union pickets, called out that they were from the 7th Pennsylvania Cavalry, arriving for duty, then took all 15 pickets prisoner. Next, they took the inner lines of pickets, also without a shot being fired. About the same time, other Confederates captured a Union hospital and the 9th Pennsylvania Cavalry in its camp.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Milroy forbade civilians from living within 800 yards of the tracks. Anyone caught doing so was to be shot on sight[/quote]

Known for his cowardly tendencies, Crittenden heard commotion in the streets and sent the hotel clerk out with his sword to tender his surrender. Rebels found the hated provost marshal, Captain Oliver Rounds, hiding between two mattresses. Most of the Southern sympathizers were being held under heavy guard, upstairs in the two-story courthouse, so Forrest’s men battered down the doors and rescued the prisoners. Then they moved across the street to the jail, where more civilians were being held. The Federal guards, realizing they would be overwhelmed, tried to shoot their prisoners, who pressed themselves against the front wall of their cell to evade the bullets. The guards then set fire to the jail, but the Confederates broke in and pried apart the steel bars enough to pull each prisoner out. By nightfall Forrest’s men had captured or killed virtually every Federal soldier (890 out of 900), and Southern loyalists breathed a welcome sigh of relief.

The Rebels held the town from July 13, 1862, until the Battle of Stones River (Second Murfreesboro), fought from December 31, 1862, to January 2, 1863. Lewis Maney and his family watched that clash from an upstairs window at Oaklands; Bettie Blackmore and her mother from a balcony at Fairmont. “The flash, smoke, and deafening noise of the artillery, the click of small arms, deploying troops in an open field, the shouts and curses of the infuriated soldiers created a memorable scene,” Bettie wrote in her journal. “At last the bloody struggle ended. Bragg withdrew…and we were surrounded by a desperate but victorious foe.”

The relative peace under Confederate protection was suddenly a distant dream, and the nightmare of armed Union oppression had returned. The Federals again tormented Southern-sympathizing families, commandeering supplies, cutting down virtually every tree, and ripping boards from houses, churches, and barns to build Fort Rosecrans and feed their fires. Confederate soldier Calvin Lowe was bedridden at his farm, still recovering from wounds he had suffered at Shiloh, when a Federal patrol stopped and helped themselves to all the food they could find. Mrs. Lowe was pregnant, but she resisted, and a soldier stabbed her in the stomach, killing her and her baby.

The relative peace under Confederate protection was suddenly a distant dream, and the nightmare of armed Union oppression had returned. The Federals again tormented Southern-sympathizing families, commandeering supplies, cutting down virtually every tree, and ripping boards from houses, churches, and barns to build Fort Rosecrans and feed their fires. Confederate soldier Calvin Lowe was bedridden at his farm, still recovering from wounds he had suffered at Shiloh, when a Federal patrol stopped and helped themselves to all the food they could find. Mrs. Lowe was pregnant, but she resisted, and a soldier stabbed her in the stomach, killing her and her baby.

Even in those dark days, Bettie dreamed of opening a school. Like many children of wealthy families she had been educated by tutors; public schools were just starting in Middle Tennessee. Though dying of tuberculosis, she finally gained enough strength to rent a house where she opened Blackmore School, which grew to 35 students by 1864.

There were other highlights of civility around Murfreesboro, like the marriage of Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan to Mattie Ready at the home of her parents, former U.S. Representative Charles Ready and his wife, Martha. But when news of the wedding reached the new Union provost, Maj. Gen. Robert Milroy, he moved his headquarters to the home and burned Ready’s cotton gin. He ordered the burning of at least a dozen other homes and seven mills, all within seven miles of Bettie’s beloved Fairmont. Troops ripped wood from the Methodist church for their fires, and destroyed the Presbyterian church, taking the bricks to build ovens in their camps. After the Emancipation Proclamation, many slaves remained with the familiarity of their plantations, though they were hungry and hopeless. One of the Ridley slaves was hired by a neighbor at $3 a month, which was typical of the new bondage in which they found themselves.

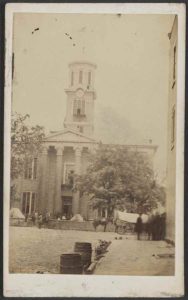

in Murfreesboro. It is one of the state’s six antebellum courthouses still operating. (Library of Congress)

Milroy issued orders for patrols to continue burning homes and hang some 500 named civilians, declaring in an 1864 letter to his wife, “Blood and fire are the methods I use.” To protect Union supply trains from guerrilla raids, he forbade civilians from living within 800 yards of the tracks, and anyone caught there was to be shot on sight. Though his troops ran roughshod, Union commander Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans was intent mainly on wiping out the area’s Southern spies, notably the Coleman Scouts—a fearless and highly secretive spy unit that moved in and out of Union lines, even in the streets of Nashville. One of them was 21-year-old Sam Davis, a friend of the Ridley family. When he was captured and hanged, Bettie wrote that he was a “blessed martyr.” Some months later, another scout, Dewitt Jobe, was tortured to death by a Federal patrol. Still, Southern-sympathizing families plotted and moved in secrecy, doing anything they could for the war effort, while their Unionist neighbors watched and reported what they saw to the authorities. After Fairmont was destroyed, Bettie and her mother took refuge in a tiny rented house. A neighbor reported to the Federals that Bettie’s husband and brother had visited there, so they burned that house just as they had burned Fairmont.

That was the world in which people like Bettie Blackmore tried to live with courage and grace amid the hardest of circumstances. Bettie painstakingly rewrote her wartime journal, which had been lost in the 1863 house fire, detailing her struggles as a teacher, wife, and daughter. Exhausted, but never disheartened, she succumbed to tuberculosis in November 1864, at the age of 32.

Joe Johnston, a regular America’s Civil War contributor, is the author of It Ends Here: Missouri’s Last Vigilante. A former Nashville resident, he now writes from Tulsa, Okla.