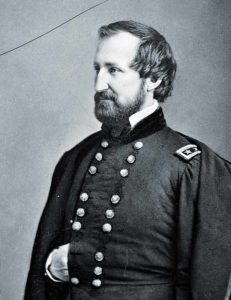

Union General William S. Rosecrans hoped to achieve peace through superior firepower

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]n February 14, 1863, while headquartered at Murfreesboro, Tenn., Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans, commander of the Union’s Army of the Cumberland, issued General Orders No. 19. It was an unusual directive with two purposes. The first few paragraphs directed that every echelon of the Army of the Cumberland—each regiment, brigade, division, and corps—create and maintain a “Roll of Honor;” publishing the names of “those officers and soldiers…who shall distinguish themselves by bravery in battle, by courage, enterprise, and soldierly conduct.” Selection was by ballot, for enlisted men, or by consensus, for officers. Each company was to nominate five privates, each regiment choosing 10 each of corporals and sergeants; each brigade four lieutenants, four captains, and two field-grade officers below the rank of colonel.

In a military era lacking almost any formal recognition for either bravery or martial skills—the Medal of Honor had only been created the previous July—Rosecrans’ roll had a distinctly Napoleonic feel. The French Emperor created the Legion of Honor in 1802 to reward both military and civilian excellence, establishing a nobility of merit rather than of breeding. Similarly, Napoleon used such distinctions to create his Imperial Guard, made up of the best and bravest, to create a combat formation second to none on any battlefield. Napoleon famously once remarked, quite cynically, that “it is with such baubles that men are led.” Rosecrans did not share Bonaparte’s cynicism, but he understood the value of recognizing merit to motivate men and inspire valor.

Rosecrans, however, was a very talented engineer as well as a soldier. As such, he devised elegant solutions to complex problems, excelling in using a single system to serve multiple needs simultaneously. The Roll of Honor applied that same principle to his army’s needs, for Rosecrans envisioned that the Roll was not just to be an administrative recognition of valor, but the source for “Elite Battalions”—a new combat formation.

Rosecrans had assumed command of the Army of the Cumberland in late October 1862, replacing Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell, who fell out of favor with the Lincoln administration. Two months later, Rosecrans fought the bloody Battle of Stones River, eking out the barest of Federal victories. That action revealed a significant shortcoming within Rosecrans’ new command. His mounted arm was both outnumbered and outfought by the Confederate cavalry he faced. At Stones River Rosecrans fielded about 5,000 mounted men. General Braxton Bragg’s Confederate Army of Tennessee deployed nearly twice as many troopers, and as spring approached, more grayclad horsemen were on the way. In response, Rosecrans thought it imperative to build up his own mounted force as much as possible.

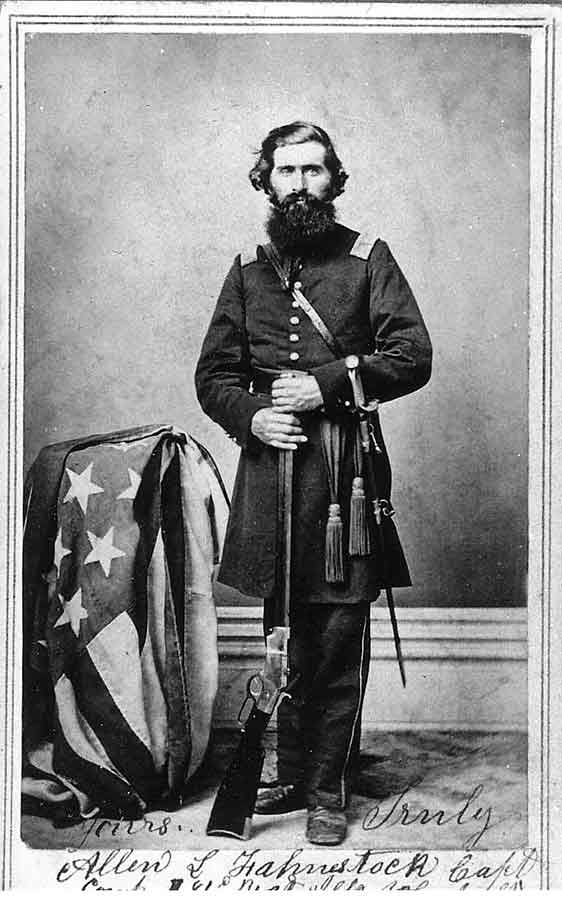

As early as November 1862, Rosecrans broached the idea of mounting some infantry regiments and to “arm them with revolving rifles, and make sharpshooters of them.” This idea was the genesis of Colonel John T. Wilder’s “Lightning Brigade” of the 17th and 72nd Indiana and the 92nd, 98th, and 123rd Illinois regiments. The image above is of Private John Munson of the 72nd Indiana carrying a Spencer repeating rifle that the members of the brigade used. Wilder’s unit has garnered plenty of attention over the years, and it is considered one of the elite Civil War field units. The 39th Indiana was also mounted in the spring of 1863 and equipped with Spencer rifles, eventually evolving into the 8th Indiana Cavalry, going so far as to adopt sabers, a weapon Wilder’s men disdained. –D.A.P.

But there were never enough Union mounted regiments, and other departments had urgent needs as well. As a stopgap, as early as the previous November Rosecrans first broached the idea of mounting some infantry regiments wholesale, and to “arm them with revolving rifles, and make sharpshooters of them.” Even though the authorities in Washington took a dim view of the idea, Rosecrans continued to pursue it.

But still more was needed. The second half of General Orders No. 19 directed that “each infantry and cavalry brigade shall immediately organize a light battalion, to be formed from the roll of honor, as follows: Three privates from each company, 1 commissioned officer, 2 sergeants and 3 corporals from each regiment, and 1 field officer from each brigade.” At strength, each battalion would number between 145 and 181 officers and men (some brigades had five regiments) all drawn from the bravest and most competent soldiers. Further, “this battalion would be provided with the best rifled arms, revolving arms, if possible, and will be mounted as soon as practicable.”

At the time Rosecrans issued this order, his army included 30 infantry brigades, which meant that by mounting their light battalions, Rosecrans intended to augment his mounted force by roughly 4,500 men who would then be available for the traditional scouting, screening, and skirmishing duties cavalry regularly preformed. They were not just meant to supplement the cavalry, however. Though not specified in the order, it is clear from subsequent events that Rosecrans intended these troops to also fight dismounted, either in line of battle or—more commonly—as brigade skirmishers.

The Confederate armies had already begun to use skilled troops as skirmishers. In April 1862, the Confederate Congress passed a law authorizing Rebel commanders to organize and recruit sharpshooter battalions, similarly hand-picked from the regiments in each brigade, and officered by men appointed by field commanders rather than state governors. The Confederate sharpshooter battalions would eventually gain much fame in the Army of Northern Virginia, and have long been associated with that army. But by the fall of 1862 there were a number of such units already serving in the ranks of the Army of Tennessee, organized over the previous summer. The most famous of these units was Major John E. “Ned” Austin’s Battalion, organized in August 1862 out of the 11th Louisiana Infantry. Austin’s command was not alone; by the Battle of Perryville the Rebel army fielded nine such battalions.

Though the Confederate sharpshooters were well-trained and eventually became tactically significant beyond their mere numbers, of necessity they remained conventionally armed, usually carrying standard issue muzzle-loading rifled muskets. Rosecrans, however, believed that Northern industry could equip his men with something better. As early as November 16, 1862—three weeks after assuming command and well before the Battle of Stones River—Rosecrans was already asking for improved weapons, informing Washington that he wished “to mount some infantry regiments, arm them with revolving rifles, and make sharpshooters of them.”

At the time, Rosecrans was much enamored of the Colt revolving rifle, designed much like the famous pistol, with a .56 caliber, 5-shot cylinder to increase rate of fire. The government supplied what it could, sending 2,500 arms of all types in November, and promising another 1,600 Colts in December; but as General-in-Chief Henry Halleck warned, there were limits: “Each army receives its proportion of each kind of arms as fast as they can be procured. This rule must be followed, for we ‘cannot rob Peter to pay Paul.’” While Rosecrans used all the Colts the War Department would send him, over time he began to favor newer, better weapons—which promised even more fire superiority.

At the end of January, still short of cavalry arms and contemplating the creation of these new formations, Rosecrans resumed his campaign for advanced weapons. On January 30 he revealed his thinking, and his impatience with what he saw as foolish government parsimony: “Revolving arms duplicate our strength. What is the use of raising and supporting a force and losing half its strength, for want of as many dollars’ expense for arms as would be lost by a day’s delay?”

This hectoring tone did not sit well with either General Halleck or Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, who knew full well that money wasn’t the problem; production was. Breechloading and repeating arms of all types were in high demand across every theater of war. There weren’t enough to meet every demand, and, snapped a clearly exasperated Halleck: “You already have more than your share of the best arms. Everything has been done, and is now being done, for you that is possible by the government….You cannot expect to have all the best arms.” That rebuke might have quelled a lesser man. Not Rosecrans.

In the meantime, Rosecrans proceeded with the organization of his battalions. On March 7, noted Lieutenant Samuel Platt of the 26th Ohio Infantry, three men of his company “were elected to the light brigade of mounted men today to have their name enrolled on a roll of honor.” Captain J.T. Patton of Company A, the 93rd Ohio, was selected to command the light company from his regiment. Years later, Patton recollected that “we bought Henry Rifles and devoted our time to special drill, being relieved from all duty except guard at Corps headquarters.”

The Henry rifle, along with the similarly designed Spencer rifle, represented the beginning of a revolution in small arms. Most existing military arms, even the Colt revolving rifles, fired paper cartridges. Such weapons were complicated and slow to load. By contrast, both the Henry and the Spencer fired premade metallic cartridges. Their design also included a tubular magazine and a lever action, allowing the firer to empty his rifle as quickly as he could work the action and pull the trigger. The .52 caliber Spencer held seven rounds; the .44 Henry, an eye-popping 15 shots. Both weapons were highly prized, and each would find a place in Rosecrans’ army. Eventually the somewhat more robust Spencer won out, garnering federal contracts to equip Union cavalry regiments and producing nearly 100,000 carbine versions. In 1863, however, both weapons were in limited supply.

The Henry apparently became the weapon of choice for the Elite Battalions, though how widespread remains unknown. Because soldiers privately purchased the repeaters, the Henrys do not show up on official ordnance returns for any Army of the Cumberland regiments. Yet Patton’s recollection is not the sole evidence of their use. Sergeant Gilbert Armstrong of Company E, 58th Indiana, also carried a Henry rifle. Labeling Armstrong “a famous sharpshooter,” the 58th’s regimental historians noted that “his rifle was a present from his fellow soldiers.” The caption accompanying Armstrong’s wartime photograph provides a bit more detail: “The gun shown…is the Henry rifle, presented to him by some of his friends in the regiment for bravery shown in the battle of Stones River.” Sergeant Armstrong’s details differ slightly from Patton’s recollections, but Armstrong was almost certainly named on the 58th’s Roll of Honor.

Prize of War

Henry rifles were also doled out to fortunate Union troops in the Eastern Theater, and the 1st District of Columbia Cavalry, raised in 1863, was one of the Federal units that received Henry rifles. An unidentified trooper of the regiment proudly poses with his Henry in the image at right. The D.C. boys put their Henrys to good use in numerous skirmishes and raids, but suffered ignominy in September 1864 when Maj. Gen. Wade Hampton’s Confederate troopers slipped behind Union lines on a raid during the Siege of Petersburg.

On September 16 Hampton’s men surprised members of the 1st D.C. who were guarding the Army of the Potomac’s large beef cattle herd at Coggin’s Point on the James River. The Henrys could not prevent the Union horsemen from staving off defeat, and Hampton’s men captured more than 2,000 head of cattle, along with 300 men of the regiment and their bright, shiny repeating rifles.

The victorious Confederates eagerly claimed the coveted weapons as trophies, and General Hampton himself took possession of a Henry rifle. He eventually gave it to his trusted adjutant, Major Henry B. McClellan, and the gun remained in the McClellan family until Skinner Auctions of Massachusetts auctioned off the trophy of the so-called “Beefsteak Raid.” –D.B.S.

An Indiana regiment took up a collection to buy Henrys for their sharpshooters, bought privately and presented to the deserving men. The 93rd Ohio served in the 2nd Division of the 20th Corps while the 26th Ohio and 58th Indiana both were part of the 1st Division of the 21st Corps; facts which suggest that by March 1863, the new formations were taking shape both rapidly and broadly throughout the army.

But the formations were against Halleck’s explicit orders, and a rebuke from him came swiftly. “The organization of light battalions,” Halleck wrote on February 19, “cannot be approved, because it is a violation of law. Volunteer troops must be organized in the manner prescribed by Congress.” Rosecrans appealed, sending wires to both Halleck and directly to Secretary Stanton on February 27. He argued that he was not raising new units, far from it: The men were only to be temporarily detailed from their regiments, a routine and regular happenstance. Men were customarily detailed for staff and logistics duties all the time. Indeed, the Army of the Cumberland’s Pioneer Corps—2,000 men organized into three battalions—had been created in exactly this fashion. No matter. In this, Rosecrans did not prevail.

It would be two more months before Rosecrans issued the necessary orders officially dissolving the light battalions. In a letter home, published in the May 5 edition of the Dayton Weekly Journal, Sergeant Troy Burkitt of the 93rd reported that “the men detailed for the ‘army elite’ will be sent back to their regiments for duty.”

But were the battalions disbanded, or did they merely revert to a more informal status? There is modest evidence that they remained in being. Also in early May, Captain George Ernst of the 15th Missouri Infantry returned to his regiment after recovering from a shoulder wound and an emergency furlough to care for his family. Instead of resuming command of Company B, however, Captain Ernst was ordered to “take command of the brigade’s battalion of sharpshooters.” Ernst’s regiment belonged to Brig. Gen. Philip Sheridan’s division of the 20th Corps, adding a third infantry division to the mix of commands that seemed to have formed light battalions.

Captain Patton of the 93rd recollected that “the War department countermanded the order and we returned to our respective commands,” but he then added, “the men of the ‘light battalions,’ with their Henry rifles did valiant service in every battle until the close of the war.” Patton’s memoir went on to describe the battalion’s service on the skirmish line in the Battle of Chickamauga in great detail; an action fought in September 1863, many months after the light battalions were supposedly dissolved. Similarly, Sergeant Armstrong of the 58th Indiana continued to wield his Henry until wounded on September 19, also at Chickamauga, whereupon the rifle passed into the hands of his lieutenant.

References to the light battalions are admittedly sparse. There is not enough evidence to determine how widespread the practice became, or how often the light battalions were used. The fact that the battalions’ lack of formal stature and that the Henrys were not government issue both mitigate against turning up evidence in the historical record. Nor did it help matters that Rosecrans was replaced soon after the Battle of Chickamauga; which in turn spelled the demise of several tactical innovations he fostered. It is this author’s belief, however, that several Army of the Cumberland brigades routinely continued to deploy their light infantry detachments as skirmishers, and that there were possibly as many as several hundred Henry rifles scattered through the ranks of that army for the rest of the war.

As for Rosecrans’ Elite Battalions, here’s hoping that more evidence emerges to document the army’s nearly forgotten light infantry.

Henry Rifles

.44, metal

cartridgeMAGAZINE

15 rounds,

magazine

under barrelWEIGHT

9 pounds,

4 ouncesCOST

$40PRODUCTION

RUN

10,000 plus

David A. Powell is nationally recognized for his tours of the Chickamauga battlefield and his five books on that engagement. His most recent work, Battle Above the Clouds, was published in June 2017. David, his wife Anne, and their blood-hounds live near Chicago.