On April 26, 1902, U.S. Army Captain John J. Pershing sat in his office at the old Spanish garrison in Iligan on the north coast of the Philippine island of Mindanao, reflecting on the brewing Moro Rebellion, months of wasted diplomatic outreach and the catalyst of much of the trouble—his immediate superior, Colonel Frank Baldwin.

Ten weeks earlier Pershing had journeyed unarmed with an interpreter and three native scouts into the heart of hostile Moro country around Lake Lanao. He’d managed to gain the respect of the Muslim datus (chiefs) and establish cordial relations with Manabilang, the most influential datu on the north shore. Pershing had returned triumphant to Iligan only to find he no longer reported to Brig. Gen. George W. Davis (commanding the 7th Separate Brigade), but to Davis’ newly arrived deputy, Baldwin, a veteran of the Civil, Indian and Spanish-American wars and a two-time recipient of the Medal of Honor. “Few doubted Frank Baldwin’s courage or pugnacity,” historian Robert A. Fulton notes, “but while a fighting man’s fighting man, at age 60 he was known to be somewhat to the right of the Sherman-Sheridan doctrine of ‘the only good Indian is a dead one.’” Within weeks the Lake Lanao Moros (aka Maranaos) had ambushed and killed two soldiers. To Pershing’s dismay Baldwin began organizing a punitive expedition to Lanao, a potential trigger for a full-scale Maranao revolt.

Maj. Gen. Adna Chaffee, the military governor of the Philippines, had his hands full with the ongoing insurrection in the north but reluctantly approved Baldwin’s expedition. However, he told Davis, “I prefer lots of talking to shooting,” and Davis in turn urged Baldwin to fight only if fired on first. Baldwin then sent an ultimatum to the Maranao datus, demanding they hand over those who had killed the soldiers. After receiving their scornful reply on April 9, he telegraphed for 1,000 men to assemble at Malabang in preparation for the march on Lanao. The move stunned Pershing and surprised Chaffee and Davis, who had heard nothing from Baldwin about the expedition since March 18. Without consultation the colonel had grabbed half the Mindanao garrison for the expedition against the enemy.

But who were the enemy? Baldwin knew the names of individuals who had ambushed the soldiers, and he had identified hostile Maranao rancherias (tribal settlements) along the Lanao shore, such as Bacolod, Bayang, Butig, Masiu and Taraca. But the rancherias were independent fiefdoms, and Baldwin did not know the extent of each rancheria’s responsibility for the attacks. Davis and Chaffee, concerned the situation might deteriorate into a general conflict between the 2,000 U.S. Army troops on Mindanao and the 100,000-strong Maranaos, journeyed down the Ganassi trail to meet with the Maranao datus. The Moros expressed their fear and anger over the forming expedition, and in response Chaffee issued another proclamation, disclaiming any intent to conquer the Maranaos but giving them a deadline of April 27 to surrender the killers.

Baldwin decided to force the issue. On April 18, after Davis and Chaffee had left and without their approval, the colonel marched his expeditionary force from Malabang some miles up the trail, ostensibly to open the road to Ganassi. The advance sparked two minor skirmishes with the Maranaos, increasing the likelihood of full-scale conflict with the Moros.

Only after the fact did Baldwin wire Davis at Zamboanga with a report of his impetuous, insubordinate actions, word of which reverberated through the highest corridors of power in Washington. Considering the state of ongoing insurrection on other Philippine islands, no one in President Theodore Roosevelt’s administration wanted a war with the Moros. Secretary of War Elihu Root himself angrily ordered Baldwin back to the coast, an order seconded by Chaffee. Davis, however, backed Baldwin, insisting a withdrawal would weaken tenuous U.S. authority on the island. Accepting Davis’ advice, Chaffee directed him to accompany Baldwin.

Back at Iligan on the north coast of Mindanao, Pershing realized Baldwin’s thrust north from Malabang had riled the previously neutral northern Maranaos. Would Mindanao flare into rebellion due to Baldwin’s prodding? It seemed probable. To reassure the Muslim tribesmen that conquest was not the intended purpose of the U.S. expedition into the heart of their territory, Pershing realized he must venture a second time into Lanao country, again unarmed. It could help prevent a general war.

Or it could mean his death.

The doughboys had arrived in the Philippines four years earlier during the Spanish-American War. When the United States assumed what was essentially colonial rule over the islands, an insurrection broke out, centered in the north. However, Moroland—comprising Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago in the south—had remained quiet. In 1899 U.S. Army Maj. Gen. John C. Bates had negotiated an agreement with the sultan of Sulu, who had nominal authority over the fractious Moros. The sultan acknowledged U.S. sovereignty and pledged neutrality, while Washington promised to keep largely out of Moro affairs.

For some six centuries the Muslim Moros of Mindanao had farmed, fished and fought—battling Christian Filipinos, the Spanish and each other with equal fervor. An insular cultural and religious minority disliked and mistrusted by the majority Christian populace, they lived within the hundreds of independent rancherias ruled by the datus. In his posthumously published memoir Kris and Krag: Adventures Among the Moros of the Southern Philippine Islands Colonel Horace Potts Hobbs offered this general description:

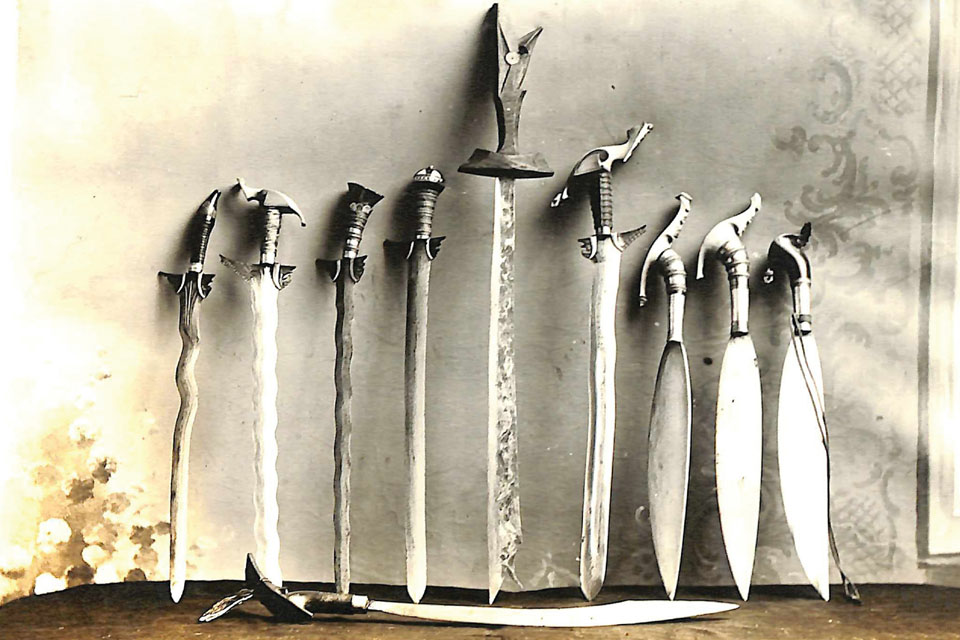

The individual Moro is, on the average, from 5 to 5 feet 7 inches tall, solidly built, erect of carriage, with red-brown complexion, straight black hair, front teeth ground concave and polished black from chewing buyo, or betel nuts.…The Moro dress is colorful and picturesque: bright colored turbans, embroidered jackets leaving the broad and often scarred chest bare, tight-fitting trousers and yards of colored sash around the waist in which is carried the brass buyo box and the razor-sharp kris, or barong.…Don’t try to bluff him or push him around, or that kris will cut you down in a flash. I have seen it done.

A year after U.S. representatives signed the Bates agreement, infantry units stationed on Mindanao violated its terms. Taking sides in a long-standing rivalry between Rio Grande Moros and the dominant Maranaos, the Americans engaged in several sharp skirmishes with the latter. The Maranaos remained hostile to the troops until Pershing’s September 1901 arrival at Iligan and subsequent diplomatic outreach. Pershing’s efforts had shown promise by early 1902, but when Baldwin landed on Mindanao in March with the newly formed 27th U.S. Infantry, he had orders to explore and improve roads into the interior—setting the stage for conflict.

On April 27 Pershing again left Iligan on the road to Marahui (present-day Marawi) rancheria, having arranged a meeting with Manabilang attended by hundreds of other Maranaos—including such diehard datus from the southern shores of Lanao as the sultan of Bayang. The warriors could have killed Pershing on the spot. Instead, they heard out the captain as he spoke through an interpreter of the Army’s intentions to find the killers, explore the lake and open the roads for commerce. Although Pershing left the conference alive and cautiously optimistic, the sultan of Bayang and others declared they would fight any U.S. troops who dared enter their rancherias.

Meanwhile, the deadline to surrender the killers came and went. Intelligence indicated the hostile Maranaos were massing at Binadayan and Pandatapan, adjacent cottas (forts) within Bayang rancheria. On April 28 Baldwin duly marched his troops north from camp on the Ganassi trail. The colonel dispersed about half of the soldiers at waypoints along his supply line, and by the time the expedition reached the open highlands at Lake Lanao, he only had 600 available fighting men, a number further reduced by malaria and other maladies.

Regardless, shortly after noon on May 2 Baldwin sent 1st Lt. Thomas Vicars’ Company F and Captain Samuel Lyon’s Company H to assault Binadayan at bayonet point. Wearing their trademark felt campaign hats and blue shirts and carrying modern Krag-Jorgensen bolt-action repeating rifles, the men scrambled across defensive ditches—and stopped, stymied by the cotta’s high, thick walls. Under point-blank fire from Maranao flintlocks and the odd Remington or Mauser rifle captured from the Spanish, the Americans hoisted one another over the walls and took the position at the cost of a single wounded man. Meanwhile, the surviving Maranaos fled across the shallow valley toward Pandatapan, the stronger cotta, ringed by trenches and foxholes.

After fortifying Binadayan hill with artillery and the 1st Battalion, 27th Infantry, Baldwin sent the four companies of 2nd Battalion to assault Pandatapan. From its parapet blood-red battle flags flapped in the breeze coming off Lake Lanao, while inside Maranaos beat gongs and shouted their defiance. As the Americans closed within a few hundred yards, the cotta erupted with the sharp crack of rifles and the roar of lantakas—forged bronze swivel cannons firing rocks, lead balls and anything else that could rend flesh. Nearing its walls, many of the soldiers stumbled into deep pits dug by the Maranaos.

As sharpshooters kept the defenders’ heads down, other soldiers maneuvered to enfilade or directly assault the enemy positions. However, the Moros were adept at close combat and charged the Americans with the double-edged kalis sword, thick, leaf-shaped barong or long, single-edged kampilan. “They fought our officers and enlisted men on the edge of the trenches, in the trenches and everywhere,” a dispatch from the front reported of the fierce fight. “It was shoot, cut, bite, throw rocks and yell for fully 30 minutes. By that time the Moros in the trenches were all dead, but our loss was heavy.”

Around dusk Sergeant William Kelleher of Company G became the first American to reach Pandatapan’s 12-foot-high south wall, soon joined by 1st Lt. Hugh Drum. Unable to scale the wall, Kelleher and Drum stood shoulder to shoulder, forming a platform for Corporal John Ward, who spent the next half-hour shooting down into the cotta at anything that moved as other soldiers handed up freshly loaded rifles. Meanwhile, Company F assaulted the main gate on the north wall, where close-range lantaka fire gruesomely decapitated Lieutenant Vicars, stopping the attack cold. Others tried scaling the wall, but the task proved impossible, and the Americans withdrew a short distance.

At nightfall a heavy rain set in. Baldwin rallied his dispirited men, ordering them to maintain a cordon around the wall and build scaling ladders for a final assault in the morning. He vowed to be the first man over the parapet. That night the Moros attempted a desperate sortie, seeking to escape. Drum later recalled the resulting “bitter hand-to-hand fights, the bayonet contesting with the kampilan, knife, sword.”

Early on the morning of May 3 the Maranao holdouts cut away the bamboo screen covering the parapet, and the Americans braced for a final suicidal rush. Instead, the Moros dropped their red battle flags and raised four white flags. As the beaten defenders emerged from the gate, two knife-wielding Moros made a slashing bid for freedom and were cut down. The diehards turned out to be the sultan of Bayang and his brother. The Battle of Bayang was over. In a sanguinary postscript that afternoon American guards killed 35 of the 83 prisoners as the Moros attempted a mass breakout. Thirty-nine got away, while soldiers recaptured nine. In all the Americans had killed perhaps 400 Maranaos and obliterated the Bayang rancheria, while U.S. casualties amounted to 10 killed and 40 wounded of some 300 men directly engaged. The next day Baldwin established Camp Vicars—named for the fallen lieutenant—as a permanent U.S. military cantonment at Lanao, a half-mile south of Pandatapan.

Chaffee thought the affair had been botched and believed Pershing had saved the Army from disaster by persuading the northern Maranaos to remain neutral. Within days of the battle Chaffee visited Pandatapan, but when Baldwin began describing the clash, Chaffee coldly cut him off, saying, “Baldwin, you have solved the problem.” But what had the fighting colonel really accomplished?

Although the Roosevelt administration and Chaffee sang Baldwin’s praises in public, it soon became clear the campaign had solved nothing. The violent incursion and high casualties had only inflamed the Moros of Mindanao, stiffening their resistance against the Americans. Bayang became a rallying cry. Chaffee needed a commander at Lanao who could handle the Moros with diplomacy and not the sword, a man with a proven track record.

He needed Pershing.

Pershing arrived at Camp Vicars in mid-May. Nominally Baldwin’s intelligence officer, in fact he was the outpost’s acting commandant and reported directly to Chaffee—a rebuke to both Davis and Baldwin. “No move will be made,” Chaffee had assured Pershing, “without your approval.” To his credit Baldwin reluctantly accepted the extraordinary arrangement, which violated every Old Army principle of rank, seniority and chain of command. Pershing, for his part, respected the old colonel, recalling him as “a fine soldier with a long experience in handling Indians, but he was inclined to be impetuous.”

The hostile Maranaos waylaid patrols sent out from Camp Vicars and even fired directly on the outpost. Casualties mounted from ambushes and increasingly accurate sniper fire. Baldwin boiled with rage, itching to march immediately on the nearby rancherias of Masiu and Bacolod. Pershing disagreed. “To move against those who are so-called enemies,” he insisted, “would force the hand of many who would like to be friends and cause them to take sides against us.”

In his own way Baldwin was much like a Moro chieftain—a proud, proven warrior, suspicious of others and quick to pull the trigger. The colonel regarded the Army’s mission on Mindanao as another Indian campaign, a challenge to U.S. authority to be suppressed with absolute force. His superiors, on the other hand, viewed the mission as the slow and peaceful establishment of a government for Moroland, with force withheld as a last resort.

The divided command could only last so long, and in June Chaffee kicked Baldwin upstairs, promoting him to brigadier general and shipping him off to the relatively peaceful island of Panay.

Once he’d taken command at Camp Vicars, Pershing sought to regain the trust of the Maranaos by holding formal conferences, developing a rapport with individual datus and establishing economic relationships. The fighting continued, however, as some rancherias proved implacably hostile, and during his 1902–03 tenure Pershing led expeditions to reduce the cottas at Butig, Masiu, Taraca and Bacolod. Unlike Baldwin, however, he sought to minimize casualties. Rather than cordoning off and frontally assaulting hostile cottas, for example, Pershing bombarded them at long range for an extended period, prompting defenders to flee and only sending in troops if necessary. In the Masiu expedition of September–October 1902 U.S. troops destroyed 10 cottas with little loss of life on either side. Pershing followed up by inviting the hostile Maranaos to Camp Vicars to talk peace. By early May 1903 the area had been pacified to the extent Pershing was able to mount an expedition along the lake to an enthusiastic welcome from most Maranaos, with hardly a shot fired in anger.

Pershing, a 40-year-old captain with dim career prospects in 1901, had by 1903 fought a successful counterinsurgency around Lake Lanao, firmly established U.S. sovereignty and won over most of the Maranao datus. Recognizing his accomplishments, in the summer of 1906 the Army took the unusual step of promoting Pershing from captain directly to brigadier general. He went on to command the American Expeditionary Forces in Europe during World War I and in 1919 was promoted by special act of Congress to the rank of general of the armies, the highest rank in the U.S. armed forces.

Pershing’s local successes did not wholly pacify Moroland. By 1903 the United States had abrogated the Bates agreement and placed the region under direct American civil jurisdiction and governance. Moro risings flared up through the first three decades of the 20th century, while Washington gradually transferred responsibility for garrisoning Moroland from the U.S. Army to the Moro constabulary, a paramilitary colonial force that recruited Moros to fight and police themselves.

Even after the Philippines won recognition as an independent republic in 1946, the Moros remained a thorny issue for its majority Christian populace. The lingering tensions ignited in the 1960s with the formation of the militant Moro Islamic Liberation Front. In 2002, at the invitation of the Philippine government, the United States again deployed troops to Mindanao, this time to help the Filipinos fight Moro groups aligned with al-Qaida.

In 2014 government officials and the Moro insurgents signed a peace agreement. The government established the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao—which includes the Lake Lanao region—granting Moros budgetary discretion, a separate police force and enforcement of sharia law for Muslims only. In return the Moros acknowledged government control of national security, foreign policy and other national-level administrative tasks.

In 2015 the United States withdrew a task force of some 500 special operations troops from Mindanao. A handful of American advisers remain. Though the troops serve in a noncombat role, their presence is an echo of an earlier chapter in America’s long and convoluted relationship with the Philippines. MH

Paul Maggioni is a first-time contributor to Military History. For further reading he recommends Moroland: The History of Uncle Sam and the Moros, 1899–1920, by Robert A. Fulton, and My Life Before the World War, 1860–1917, by John J. Pershing.