[dropcap]A[/dropcap] lonely block of mountain dominates the road to Heart Mountain Relocation Center in northwestern Wyoming, one of 10 camps that held interned Japanese Americans during World War II. The Crow Indians, who saw in its peak a resemblance to a buffalo heart, named the unusual formation. A geological enigma, Heart Mountain’s limestone summit is 300 million years older than the rock basin below.

In a cruel twist of fate, the upside-down mountain would reflect a topsy-turvy time of contemporary history, when eventually more than 110,000 unfortunate souls—60 percent of them American citizens—found themselves caught in a vise grip of paranoia and hysteria brought on by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. At the Heart Mountain camp, 14 miles northeast of Cody, enough Japanese Americans were imprisoned behind barbed wire during the war—nearly 14,000 in total—to make it the third-largest “city” in Wyoming at the time.

On February 19, 1942, 10 weeks after the Pearl Harbor attack, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. It authorized the immediate removal of all persons of Japanese ancestry living in areas U.S. military authorities had declared “Exclusion Zones”—all on the West Coast, where the country’s Asian population was densest—and moving them into remote, heavily guarded “relocation centers” further inland. The displaced were allowed to take only what they could carry. In the process, they left behind their homes, businesses, careers, and friends to face a future and fate unknown.

Roosevelt’s decision rested in good part on pressure from many West Coast politicians and on the rationale of Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt, who was responsible for West Coast security as chief of Western Defense Command. “The Japanese race is an enemy race,” DeWitt argued in a February 1942 report, “and while many second- and third-

generation Japanese born on United States soil, possessed of United States citizenship, have become ‘Americanized,’ the racial strains are undiluted.”

Construction at Heart Mountain began in June 1942; on August 11 it received its first residents. So many came from California—the majority from Los Angeles County—that the then-governor of Wyoming called Heart Mountain “California’s dumping ground.”

I first saw the camp on August 20, 2011, when I attended the dedication of its new museum, the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center. I met Norman Mineta, former U.S. Secretary of Commerce and U.S. Secretary of Transportation, who spent several years as a boy interned at Heart Mountain with his family, and spoke of the importance of being “vigilant in our protection of our constitutional rights” to ensure that our past mistakes are not repeated. The keynote speaker, Hawaii Senator Daniel Inouye, was living on Honolulu at age 17 when the Japanese attacked. The son of a Japanese immigrant, Inouye recalled spotting the Japanese Rising Sun on the wings of aircraft careering overhead and thinking, “At that moment I knew my life had changed.” In short order, it did, with Inouye and other loyal Americans being treated as “Enemy Aliens.”

Although eager to prove their loyalty, Japanese Americans were initially barred from fighting in the war. Restrictions finally lifted in February 1943, and more than 800 men and women from Heart Mountain served in the U.S. armed forces, with many of the men fighting in Europe. The Japanese American 442nd Regimental Combat Team became the United States’ most decorated military unit for its size and length of service. Twenty-one of the regiment’s warriors received the Medal of Honor; one of them was Daniel Inouye.

Today, Heart Mountain Interpretive Center is a testament to the illogicality of war. Bland and lackluster from the outside, the Center is a barracks-style building designed to evoke the original barracks and the bleakness of camp life. As I stand before it, the mid-morning summer sun blazes down on my skin. It is a dry, intense heat that saps your energy. There are no trees or shade around me, only the sun’s blistering rays. Out front, an American flag gently flaps in the slight breeze.

Inside, a docent hands me a rectangular paper tag, similar to the numbered tags the government used to identify internees and their luggage, and ushers me into the theater for an introductory film. In All We Could Carry, by Academy Award-winning filmmaker Steven Okazaki, whose father was interned at Heart Mountain, 12 former residents talk about life behind the barbed wire. “You can’t always be worrying about what you lost. You have to just keep on going,” one says.

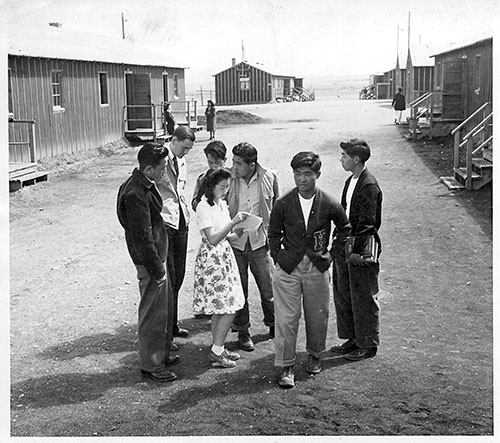

Afterward I tour exhibits depicting a timeline of the roundup of West Coast Japanese, and stories of how the FBI knocked on doors in 1942, issuing ID tags to each Japanese occupant. Throughout, museum displays are artfully and effectively built around life-size photo cutouts of residents, taken from historical images. The progression shows families packing their entire lives in their bags, with suitcases and clothing from the time bringing the point home. People with quizzical expressions board buses and trains to Heart Mountain, transporting them to an unknown future.

Most poignant is the display of two adjoining rooms in a typical barracks. A disturbing reminder of what greeted evacuees once they arrived, the first is a crude wooden shanty with uninsulated walls, a bare window, and military cots. The adjacent room shows what the same room looked like once occupied, and with touches added—a quilt, a toy—to make the space feel more like home. Privacy was nonexistent, save for the occasional improvised bed sheet hung from the ceiling. Residents shared bathroom and laundry facilities and ate their meals in communal mess halls.

The museum’s main room is dedicated to camp life. While armed military police guarded the 46,000-acre facility from nine towers, internees tried to create normalcy inside. They built and worked in camp schools, movie theaters, and hospitals—where they delivered more than 550 babies conceived in confinement—and created photography clubs, sports teams, writing, woodcarving, sewing and knitting classes, and Boy and Girl Scout groups. I thought back to the Center’s inaugural opening, and Norman Mineta’s story of how, as a 12-year old, he had befriended 12-year-old Alan K. Simpson, a future Wyoming Senator. They met at a Boy Scout jamboree, somehow cutting across barbed wire and barriers to forge a lasting friendship.

To improve nutrition and vary their diet, inmates dug an irrigation canal and cleared the land of sagebrush. Gardening was a struggle, but hard work transformed once-barren earth into fields of food. Sweet peas, tomatoes, squash, cucumbers, and daikon radishes supplemented their diet while helping the facility become more self-sufficient. In August 1944, the camp newspaper, the Heart Mountain Sentinel, reported “an all-time high in harvesting,” describing the abundance of produce grown that year from the gardens. Today, a victory garden replicates crops grown by Heart Mountain’s internees.

My last stop is the Reflection Room, where visitors inscribe thoughts on their ID tags and hang them on barbed wire lining a wall. Large windows frame Heart Mountain in the distance. “We must never forget the lessons of Heart Mountain, even as the ‘face of evil’ changes,” one reads. “We had no idea about this camp or that there were so many of them,” says another. “Thank you for teaching us about this truly tragic time. May we never repeat it.”

It was a time when America lost its heart.✯