At the signing of the 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie—in what four decades later would become the state of Wyoming—U.S. commissioners arbitrarily appointed Conquering Bear, a 50-something Brulé Lakota, first chief of all the Sioux. But three years later Conquering Bear was shot in the back, possibly by mistake, as he stalked away from a negotiation with U.S. Army Lieutenant John Grattan over reparations for a cow killed by a visiting young warrior from the Minneconjou tribe. In the short, sharp fight that followed, the Lakota warriors riddled Grattan, his half-blood interpreter and 29 soldiers with dozens of arrows. In addition to the mortally wounded Conquering Bear, the soldiers had wounded a Lakota warrior and two women. Trader James Bordeau, who watched the fight from his post, and a mortally wounded soldier affirmed the troops had fired first and for no good reason. The Brulés carried the first chief of all the Sioux far from the hated fort to die on the prairie, while the furious younger warriors looted Bordeau’s trading post before making their escape.

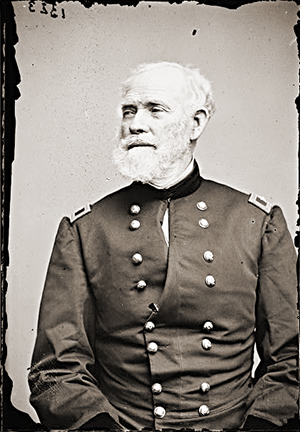

Secretary of War Jefferson Davis promptly recalled Colonel William S. Harney, a hardened veteran of the Seminole and Mexican wars, from leave in Paris to lead a punitive expedition. After exhaustive preparations and numerous delays, Harney’s expedition finally set out from Fort Leavenworth on Aug. 4, 1855. In early September, en route to Fort Laramie, the column caught up to Chief Little Thunder’s Brulé encampment at Ash Hollow along the North Platte River. Harney surrounded the village and ordered Little Thunder to surrender the men who had participated in the Grattan incident. In a brief parley on September 3 Little Thunder refused the demand, and Harney unleashed his attack the minute deliberations were over. Riddled with long-range fire from Sharps rifles and then ridden down by cavalrymen, the Brulés took an awful beating. When the firing finally ceased, 86 Indians and four soldiers lay dead or dying. Those unable to escape—some 70 women and children—surrendered to the soldiers.

At the end of his campaign Harney, thereafter known to the Indians as “Mad Bear,” called for another treaty council, at Fort Pierre in early March 1856, during which he would appoint another first chief of all the Sioux. While 6-foot-6 Little Thunder was in his prime—in his mid-30s, strong and respected among his people—he overtly hated Harney. The chief Harney and the Bureau of Indian Affairs ultimately found acceptable was Bear Ribs.

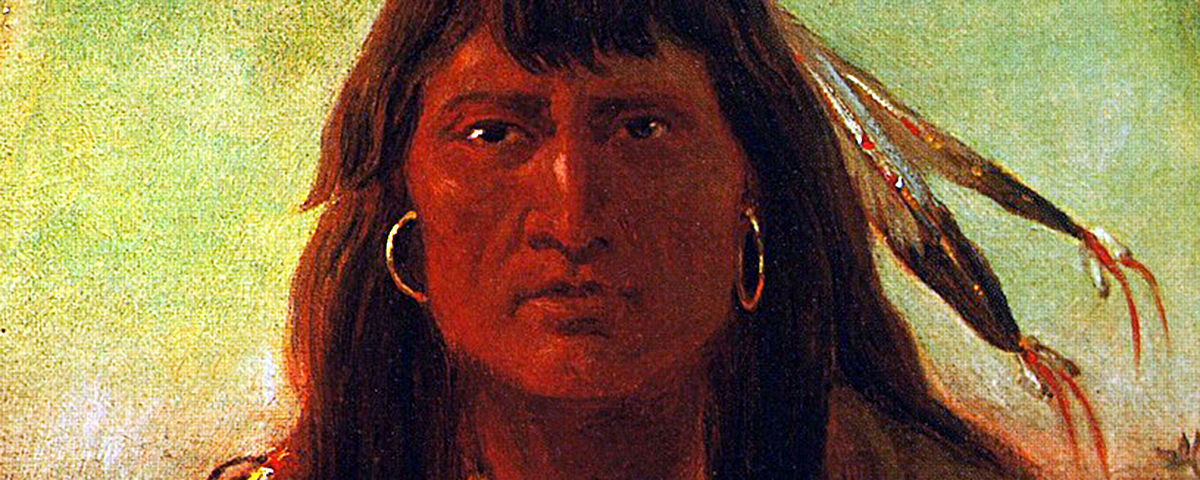

Bear Ribs (also recorded as Bear’s Rib), a Hunkpapa from the Missouri River region, was born circa 1812. As captured by German-born painter Karl Wimar shortly after Harney’s 1856 appointment, the chief was a sturdy middle-aged man with a square jaw, an aquiline nose and an intelligent but honest gaze. Bear Ribs was essentially committed to peace. He and his band had actually taken up farming in a small way. He had two wives—sisters who were daughters of Chief Many Eagles of the Yankton Sioux, historic protectors of the pipestone quarry (in present-day Minnesota) who had also embraced farming. Bear Ribs spoke often with Jesuit missionary Father Pierre-Jean De Smet, and some sources report the chief was a convert to Catholicism. At very least he respected the white missionaries and Quakers. But over the next half-dozen years Bear Ribs would lose the respect of many of his own kinsmen, and in June 1862 the first chief of all the Sioux would die at their hands.

Lieutenant Gouverneur Kemble Warren of the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers first encountered Bear Ribs in fall 1857 as Warren and four other scientists surveyed, mapped and sketched the largely unknown Black Hills region with Lieutenant James McMillan and an escort of 30 soldiers. The Hunkpapas arranged a hostile though nonviolent reception for the party east of Fort Laramie, at which they informed the white men the Indians were engaged in a buffalo hunt and did not want the bison disturbed. “I consented,” Warren recalled in his survey notes, “to wait three days without advancing, in order to meet their great warrior, Bear’s Rib, appointed first chief by General Harney’s treaty, merely changing our position to one offering greater facilities for defense.” When Bear Ribs failed to show, the survey moved east toward Inyan Kara Mountain, marking it down as a landmark. Warren recorded:

We were overtaken by Bear’s Rib and one other Indian who accompanied him. He reiterated all that had been said by the other chiefs and added that he could do nothing to prevent our being destroyed if we attempted to proceed further. I then told him that I believed he was our friend, but that if he could do nothing for us, he had better return to his people and leave us to take care of ourselves, as I was determined to proceed as far as Bear Butte. After a whole day spent in deliberation, he concluded to accompany us a part of the way, and he said he would then return to his people and use his influence to have us not molested. In return for this he wished me to say to the president and to the white people that they could not be allowed to come into that country; that if the presents sent were to purchase such a right, they did not want them. All they asked of the white people was to be left to themselves and let alone; that if the presents were sent to induce them not to go to war with the Crows and their other enemies, they did not wish them. War with them was not only necessity but a pastime. He said General Harney had told them not to go to war, and yet he was all the time going to war himself. (Bear’s Rib knew that when General Harney left the Sioux country, he had gone to the war in Florida and was at that time in command of the army sent against the Mormons.) He said, moreover, that the annuities scarcely paid for going after them; and that if they were not distributed to them while they were on their visit to the trading posts on the Missouri to dispose of their robes, they did not want them. (It is a fact that for several years, owing to this cause, these Indians have not come in for their goods at all.)

He said that he heard that the Ihanktonwans [Yanktons] were going to sell their lands to the whites. If they did so, he wished them informed that they could not come on his people’s lands. They must stay with the whites. Every day the Ihanktonwans were coming there but were always turned back.

Whatever may have been Bear’s Rib’s actions after leaving us, it is certain we saw no more Indians in the Black Hills.

Warren had helped patch up wounded Lakota women and children after Harney’s September 1855 attack at Ash Hollow (aka Blue Water Creek), and Bear Ribs may have known that, or perhaps he simply admired the lieutenant’s palpable intelligence. Regardless, the chief’s primary goal was to keep the peace. He knew the Lakota were outmatched.

Bear Ribs’ main opposition, however, rose from within his own ranks. The Hunkpapas were intensely cautious. They had come to accept French fur traders. But those of his tribe who were not “Laramie loafers” bluntly told their nominal first chief and other leaders to turn away any other whites bearing gifts.

Bear Ribs’ blunt talk had a way of making enemies—on either side of the divide

The tipping point came in the spring of 1862 when Judge Samuel N. Latta, the appointed agent for the Lakota bands, pressed the Hunkpapas to accept their annuities at Fort Pierre. John Mason Brown, a young Kentuckian, was a witness to the proceedings:

May 28 – Wednesday.…The chiefs of five bands refused the annuities, and ‘Bear Rib,’ grand chief of all, demanded that the Arricara [Arikara] annuities should be give up, the Sioux being at war with that tribe. I have never seen a more humiliating sight than the terror of Latta when the chiefs declared they would detain us and the boat until the Arricara goods were given up. He turned pale and shook with fear, as if an ague were on him. A fight seemed imminent. [Indian trader Pierre] Chouteau requested me to take care of the defense of the boat.…[We] had posted 20 picked men and loaded all arms so well as to feel certain of getting the best of the fight, when the agent [Latta] ignominiously acceded to the demand and surrendered the Ree annuities. He came on board and retreated to his stateroom. The boat was cast loose at 5 p.m. amid the curses of the passengers & the huzzas of the Sioux.

“At the Unkpapa [sic] agency on the upper Missouri,” a period history of the region affirms, “some trouble was experienced in getting the Indians to accept the goods sent out by the U.S. government. The agent, Samuel N. Latta, finally prevailed on one of the chiefs, named Bear’s Rib, to accept the portion due his band. Bear’s Rib reluctantly consented, telling the agent at the time that he feared his people would kill him for accepting the goods.”

“Bear Ribs was the spokesman,” wrote historian Josephine Waggoner, who had interviewed many of the chief’s contemporaries. “He told Mr. Latta that he had been a lifelong friend of the white man and the government, that he had always been obedient to their wishes, and that to show his friendship he would accept the annuities this time, as long as they were brought and unloaded, although the act endangered their lives. But Bear Ribs warned Mr. Latta not to bring anymore goods unless they brought soldiers along to guard them and to keep them from being destroyed.”

The elders Waggoner interviewed said Bear Ribs gave away most of the annuities to “hostile” Sioux bands, including Sitting Bull and his followers, who had not wanted to accept handouts directly from the whites, thus ameliorating their anger, albeit temporarily. The elders further claimed that Bear Ribs offered to act as a middleman, trading buffalo robes and furs to the Fort Pierre traders for hardware and dry goods—but that the ongoing Civil War had delayed all deliveries along the various rivers.

Bear Ribs was not the only Lakota advocating peace. Some months earlier Kills Game and Comes Back, a young Sans Arc Lakota warrior, had dreamed of 10 black stags, the lead of which told him, “Do good for the people.” Already known as a generous people, the Sans Arcs (“Without Bows”) got their name for using unmarked arrows in buffalo hunts so that anyone who had missed his mark could claim any buffalo he found without embarrassment. In the wake of his vision Kills Game had gathered with friend Charger and three other young warriors for a feast, at which they asked a medicine man named Charging Dog for insight. “We may be brave in battle,” Charging Dog said, “but as everybody knows, we do not live long, and to do each other harm in our camp is very bad. I have seen a lot of it during my life. I believe the hardest thing for anybody to do is to do good to others, but it makes their hearts rejoice.”

Inspired by the medicine man’s words, the five young Sans Arcs had organized a warrior society for peace. Less placable Lakotas branded them the “Fool Soldiers,” as they pledged to lay down their own lives if it would prevent Indians from killing Indians.

Days after the traders landed the annuities at Fort Pierre under Bear Ribs’ grudging acceptance—and after the chief’s reported failure to barter robes and furs for trade goods—the chief visited the fort to meet with U.S. representatives. Though his father-in-law and wives were Yankton and presumably amenable to selling their lands to whites, Bear Ribs voiced his opposition any further such sales. He also objected to the cession of any more Hunkpapa land to the Yanktons. “We lent them what they had to grow corn on it,” the chief complained. “We gave them a thousand horses to keep that land for us, but I never told them to steal it and go and sell it.…If those men, who did it secretly, had asked me to make a treaty for its sale, I should not have consented.”

Bear Ribs painted agent Latta and the less scrupulous Yanktons as liars: “[Latta] takes my words and puts them into the water and makes other reports of what words I send to my great father. I believe there are poor people below [the Yanktons] who put other words in the place of what I say.”

The irate first chief also said the agreement the Lakotas had made with Harney, under duress, was not being enforced. Wagon trains were traveling through and “landing in” their country despite the government’s promises. Bear Ribs’ blunt talk had a way of making enemies—on either side of the divide.

Word soon reached Charger and the other Fool Soldiers that someone had threatened to kill Bear Ribs for again conferring with the treacherous whites. To safeguard the first chief, the Fool Soldiers had him stay in their own tepee just outside the Fort Pierre gates. On the morning of June 6 someone came to the flap of the tepee and on some pretense asked in Lakota to speak with Bear Ribs. When the first chief stepped outside, his callers shot him and ran for it. (A 20th century account that he was shot in a mass gunfight is not widely believed.)

In the wake of the shooting, factions from either side converged for battle, the Hunkpapas to avenge Bear Ribs—though some had resented his very willingness to meet with the whites—and the Yanktons to assert their rights to a reservation Bear Ribs had opposed. Charger and his Fool Soldiers stood in their midst and somehow managed to arrange another feast, assigning women of each tribe to prepare their own specialty. Amid threats and glowering looks, Charger addressed the throng. “It is a disgrace to fight among ourselves,” he began. “We are all related. I call the son of Chief Bear Ribs forward, so I may give him a horse in his sorrow.” The expiation horse and appeal to brotherhood worked—though perhaps in part because no one was sure who had actually killed Bear Ribs. The Sioux Nation averted its own civil war as the factions either scattered or returned to peaceful trading at Fort Pierre.

‘He had no ears,’ wrote the Hunkpapa chiefs of Bear Ribs, ‘and we gave him ears by killing him’

At the time of the shooting Bear Ribs’ death was a murder with many suspects. The Yanktons had good reason to dislike him, as did the Arikaras. But seven weeks later agent Latta received the following letter from the Hunkpapas:

We have this day requested Mr. [Pierre] Garreau [a trader and interpreter] to deliver to you this, our message. It is our wish that you stop the boat belonging to Mr. [Charles] Galpin at this place and send her back, as we don’t want the whites to travel through our country. We claim both sides of the river, and boats going above must of necessity pass through it.

We do not want the whites to undertake to travel on our lands. The Indians have given permission to travel by water, but not by land; and boats carrying passengers we will not allow. If you pay no attention to what we now say to you, you may rely on seeing the tracks of our horses on the warpath.

We beg of you for the last time not to bring us any more presents, as we will not accept them. As yet we have never accepted of your goods since you have been bringing them to us. A few of our people have been in the habit of receiving and receipting for them, but not with the consent of the nation or the chief soldiers and headmen of our camp.

We notified the Bear’s Rib yearly not to receive your goods; he had no ears, and we gave him ears by killing him. We now say to you, bring us no more goods; if any of our people receive any more from you, we will give them ears as we did the Bear’s Rib. We acknowledge no agent, and we notify you for the last time to bring us no more goods. We have told all the agents the same thing, but they have paid no attention to what we have said. If you have no ears, we will give you ears, and then your Father very likely will not send us any more goods or agent.

We also say to you that we wish you to stop the whites from traveling through our country, and if you do not stop them, we will. If your whites have no ears, we will give them ears.

The whites in this country have been threatening us with soldiers. All we ask of you is to bring men and not women dressed in soldiers’ clothes. We do not ask for soldiers to fight, without you refuse to comply with what we ask.

We have sent you several messages, and we think you have not received them; otherwise we would have heard something from you. We are not certain that you will ever hear what we now say. You may get this and you may tear it up and tell your Father that we are all quiet and receive your presents, and by this means keep your place and fill your pockets with money, while our Great Father knows nothing of what is going on but is like a blind old woman that cannot see. We beg of you for once to tell our Great Father what we say, and tell him the truth.

The remarkable letter bore the marks of nine Hunkpapa chiefs—Feather Tied to His Hair, Bald Eagle, Red Hair, The One That Shouts, Little Bear, Crow That Looks, Bear Heart, Little Knife and White at Both Ends. Their blunt sentiments encapsulated Sitting Bull’s later policy—leave us alone.

Bear Ribs’ death was truly tragic. By trying to avoid a war he knew could not be won, without betraying the trust of either side, he won the enmity of both sides. The bullet that killed him was fired by another Indian. But in the end he was a victim of his own integrity. Bear Ribs was the last man ever to accept the U.S. appointment as first chief of all the Sioux. But his son and namesake also became a chief, and the family remains prominent on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, firmly straddling the border between North and South Dakota. WW

Wild West special contributor John Koster is the author of Custer Survivor. Suggested for further reading: Witness, by Josephine Waggoner, and Exploring the Black Hills, 1855–1875: Reports of the Government Expeditions.