If the book (and 1943 movie) title “Guadalcanal Diary” rings a bell, odds are that you have heard of the journalist Richard Tregaskis, who wrote the book. In that bestseller, Tregaskis told the story of the World War II battle as a war correspondent who was in the thick of the action with U.S. Marines during the first few weeks of August and September 1942. The New York Times called the book “one of the literary events of its time.”

Odds also are that you didn’t know Tregaskis covered the wars in Korea and Vietnam and in 1963 published the award-winning Vietnam Diary, a personal account offering a slice of a very different war.

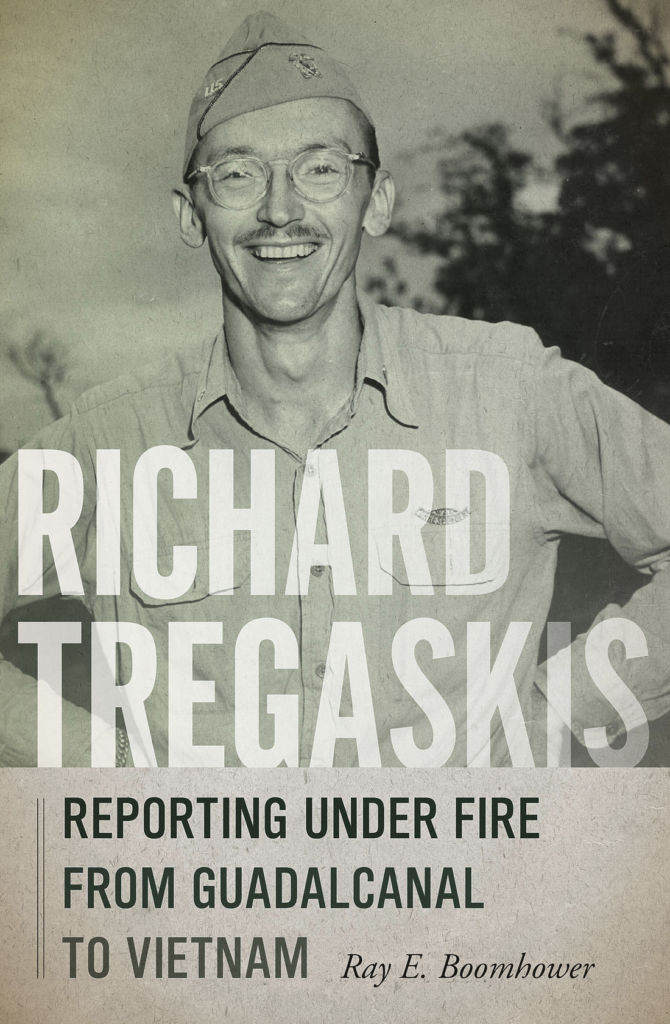

In Richard Tregaskis: Reporting Under Fire from Guadalcanal to Vietnam, biographer Ray E. Boomhower provides a revealing, in-depth picture of his subject’s life. Boomhower takes the reader into the trenches with Tregaskis as he chronicles the journalist’s courageous, award-winning coverage for the International News Service in both the Pacific and European theaters of World War II. Boomhower, a senior editor at the Indiana Historical Society Press, also includes a detailed account of Tregaskis’ lesser-known experiences covering the Vietnam War.

The gangly, bespectacled, 6-foot-5-inch Harvard-educated reporter grew up during the Depression in Elizabeth, New Jersey. Tregaskis developed his brand of personalized journalism as a newly minted war correspondent, relying heavily on the daily dairies he kept as he enmeshed himself into the lives of the Marines on Guadalcanal. He went on to spend countless hours with American troops in Europe, where he suffered a serious head wound near Cassino, Italy, and later in Korea and Vietnam.

Tregaskis continued to practice his form of personal journalism when he arrived in Vietnam in October 1962 during the rapidly expanding U.S. advisory effort. For the next three months he again put himself in danger, attached to Marine, Army and Special Forces units because—as he put it—the “most dramatic and exciting stories in war are found where the action is.”

He held the then widely accepted view in America that it was necessary for the U.S. to help stop communism in Southeast Asia before it spread throughout the world. Tregaskis also believed his reporting should support U.S. policy and shine a positive light on the troops doing the fighting.

That put him at odds with the younger generation of war correspondents in Vietnam in the early 1960s, primarily David Halberstam of The New York Times, Malcolm Browne of The Associated Press and Neil Sheehan of United Press International. Like Tregaskis, they came to Vietnam believing the U.S. had an obligation to stop communism there and certainly supported American troops. (Browne and Sheehan were both U.S. Army veterans.) Yet they also believed, in Boomhower’s words, that it was their job “and the responsibility of other journalists in Vietnam to report on the news, positive or negative” and that “pointing out errors in how the war was being run was helping the troops in the field.”

Tregaskis never wavered from his hawkishness and belief that negative reporting on the war was a disservice to military personnel in harm’s way. Tregaskis held that view to his dying day, Aug. 15, 1973, when he suffered a heart attack and drowned near his home in the waters just off Ala Moana Beach in Oahu, Hawaii. He was 56 years old.

Richard Tregaskis

Reporting Under Fire from Guadalcanal to Vietnam

by Ray Boomhower, High Road Books, 2021

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.