Operation Abilene, launched on Easter Sunday, April 10, 1966, was one of the U.S. Army’s first large combat operations during the Vietnam War. That day, Sgt. James W. “Jim” Robinson Jr.’s Company C, 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division, began hacking its way through dense jungle near Xa Cam My in the coastal regions of Phuoc Tuy province east of Saigon.

While most units of the 1st Division saw only limited engagements in their search-and-destroy missions during Operation Abilene, Company C was “hung out there as a tempting target,” as troops in Vietnam would say, patrolling near a 400-man Viet Cong battalion. On the next day, the “bait” prompted a response. Over the next 24 hours the company suffered 80 percent casualties.

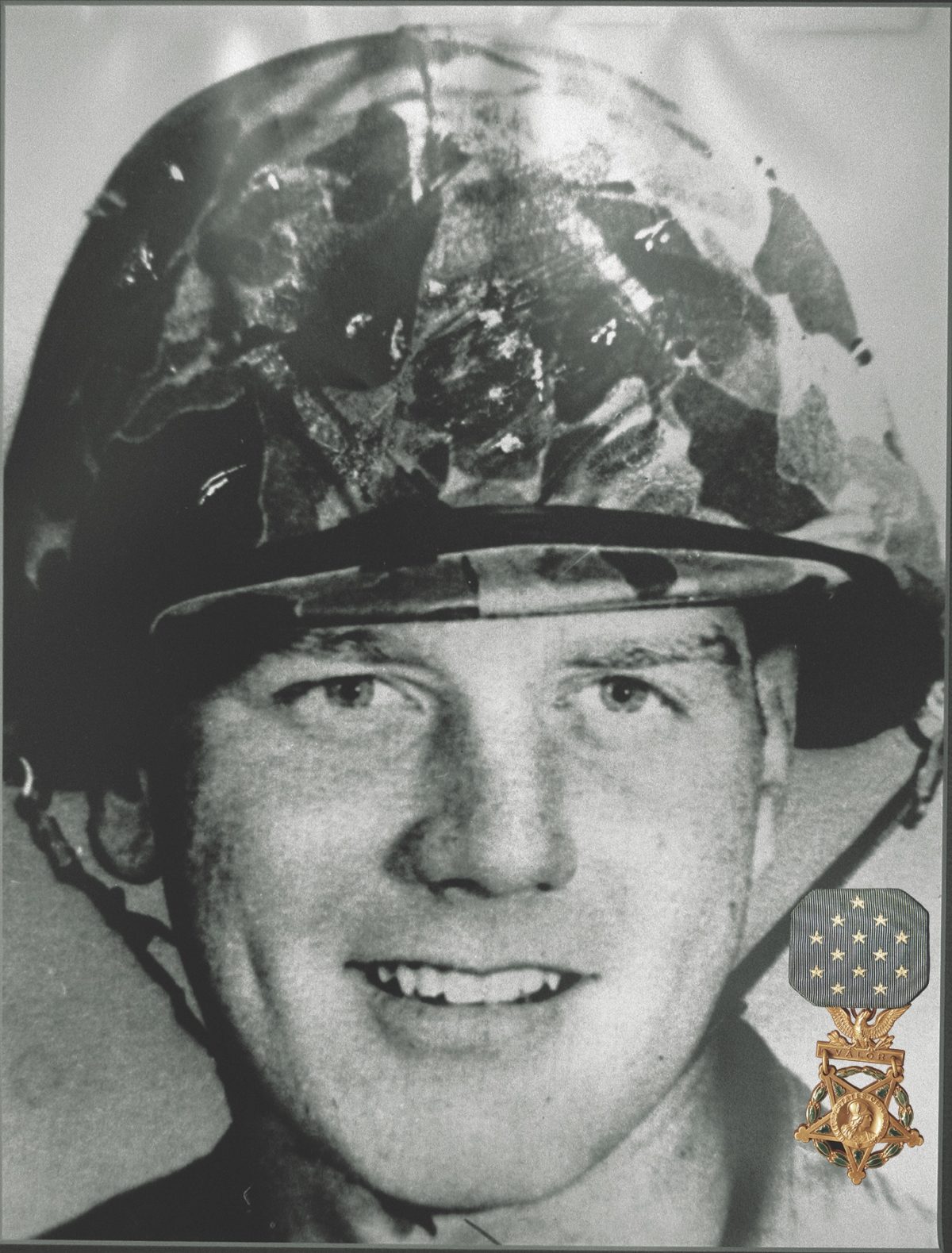

Robinson, born in the Hinsdale suburb of Chicago, on Aug. 30, 1940, enlisted in the Marine Corps in 1958 after graduating from Morton High School in Cicero, Illinois. He was discharged in 1961 and settled in Northern Virginia, where he watched the growing communist invasion of South Vietnam with concern. “There’s a world on fire and we should do something about it,” he wrote in a letter to his father. On Dec. 9, 1963, Robinson enlisted in the Army, hoping to become an adviser to Vietnamese troops.

Ordered instead to Panama as a military policeman, Robinson began a yearlong letter-writing campaign seeking transfer to Vietnam. Finally, in August 1965 he was assigned to the 1st Infantry Division and got his wish.

Shortly after noon on April 11, 1966, Company C’s 3rd Platoon broke into a hidden Viet Cong base camp and was hit with sniper fire. American artillery responded to support the operation, but one round fell short and detonated in the jungle canopy, killing two men and wounding 10.

Robinson, a 1st Platoon fire team leader, ordered his men to clear a landing zone so medevac helicopters could extract the wounded. However, the men were unaware that they were working within yards of their primary objective—the Viet Cong battalion’s command post. Almost immediately, 10 enemy machine guns blanketed the area, while a torrent of sniper fire rained from the trees, and mortars added to the devastation.

Amid the pandemonium, the American soldiers clambered for any semblance of cover. Their cool-headed sergeant organized defensive fire and moved among them to bolster their confidence. Robinson used his M79 grenade launcher to silence a menacing sniper. When a medic was struck while bandaging an infantryman, he rushed into the open and dragged both men to safety.

After another American was hit, Robinson ran to him and soon felt enemy rounds slamming into a shoulder and leg but still managed to get the man to shelter. While administering first aid and treating his own serious wounds, he spotted a machine gunner inflicting heavy casualties on the platoon.

Out of rifle ammunition, Robinson armed himself with grenades to attack the machine gun. A Viet Cong tracer bullet—treated with a chemical that makes its trail glow—hit him in the leg and ignited his trousers. The sergeant ripped off part of the burning uniform and pressed on.

At 6 feet, 3 inches, Robinson was an inspiring sight—but also a large target. Two rounds pounded his chest but couldn’t stop him. Only after getting close enough to throw two grenades that destroyed the enemy position did he finally fall.

On July 16, 1967, Secretary of the Army Stanley A. Resor presented the Medal of Honor to Robinson’s family. Four years later James W. Robinson Secondary School opened in Northern Virginia’s Fairfax County. Robinson’s father donated the medal to the school, and it remains on display as an inspiration to students who recall the man who wrote in a letter to his father: “The price we pay for freedom is never cheap.”

—Doug Sterner, an Army veteran who served two tours in Vietnam, is curator of the Military Times Hall of Valor, the largest database of U.S. military valor awards.

This article appeared in Vietnam magazine’s December 2019 issue.