[dropcap]T[/dropcap]hey did it. On April 18, 1943, 16 U.S. Army Air Forces fighter pilots from Guadalcanal flew more than 400 miles to ambush Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto as he flew to Balalae airfield in the Solomon Islands. They sent the Japanese Combined Fleet’s commander in chief to a fiery grave in the jungles of Bougainville. The United States had exacted revenge against the architect of the Pearl Harbor attack and one of the Imperial Navy’s highest-ranking officers—but at what cost?

Behind the scenes, President Franklin D. Roosevelt reacted with glee, writing a mock letter of condolence to Yamamoto’s widow that circulated around the White House but was never sent:

Dear Widow Yamamoto:

Time is a great leveler and somehow I never expected to see the old boy at the White House anyway. Sorry I can’t attend the funeral because I approve of it.

Hoping he is where we know he ain’t.

Very sincerely yours,

/s/ Franklin D. Roosevelt

Ironically, the success of the mission, aptly named Operation Vengeance, threatened to expose the most important secret of the Pacific War: the U.S. Navy’s ability to read the Japanese navy’s top-secret JN-25 operational code. If the Japanese suspected a broken code had led to Yamamoto’s death, they would drastically overhaul all their military codes and the United States would lose its priceless strategic advantage. As nervous commanders waited to see if there would be a day of reckoning, America’s own servicemen would prove to be the gravest threat to this crucial secret.

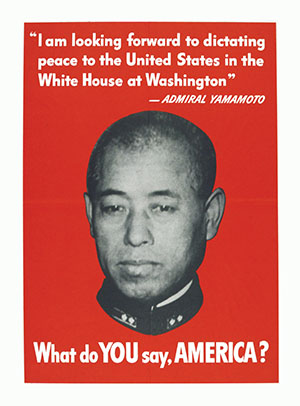

Yamamoto, then 59, was one of the most hated men in America. Not only had he planned the attack on Pearl Harbor; almost as galling, he had reportedly bragged that he was “looking forward to dictating peace to the United States in the White House.” In reality, he had never made this boast. It was a product of Japanese propaganda, but Americans took it as the gospel truth.

The Japanese navy, widely deployed throughout the Pacific, heavily relied on coded radio transmissions to send many of its most secret messages—and the U.S. Navy was listening. American cryptanalysts had broken the latest version of the JN-25 code just in time for the Battle of Midway in June 1942. With advance knowledge of Japanese plans, the outgunned U.S. Navy inflicted a stunning defeat on a superior enemy force.

The cryptanalysts were about to score again.

In early April 1943, Yamamoto planned a one-day inspection trip from Rabaul to bases around the southern tip of Bougainville. In preparation, his staff sent the itinerary to local commanders. Although the staff wanted Yamamoto’s schedule hand-delivered to Bougainville, Japan’s Eighth Fleet naval headquarters was so confident in the security of the JN-25 code that it sent the message by radio.

The Japanese had modified parts of their JN-25 code on April 1, as they periodically did, but for U.S. Navy code-breakers it was only a temporary setback—the basic code system remained unchanged. Therefore, American cryptanalysts could soon read large parts of new messages. On April 14, they intercepted and decoded Yamamoto’s travel schedule. It was a code-breaker’s dream. As he read it, Marine Lieutenant Colonel Alva Lasswell, one of the top cryptanalysts, exclaimed, “We’ve hit the jackpot.”

The decoded itinerary not only included the date and precise times for Yamamoto’s upcoming visits to the bases on Bougainville, but also revealed that he would be flying in a twin-engine bomber escorted by only six fighter planes. Ironically, his inspection tour was set for April 18, 1943, exactly one year after the Doolittle Raid on Tokyo.

Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, conferred with Commander Edwin T. Layton, his chief intelligence officer. They understood that this could be their only chance to get Yamamoto because it might be the closest he would ever venture to the front. They calculated that American P-38 Lightning fighters based on Guadalcanal could fly the more than 800-mile round trip distance to Balalae airfield and back.

Nimitz knew that if the Japanese thought Yamamoto had been ambushed, they could suspect their code had been broken and change it. He decided the risk was worth it, because the Japanese had no one of comparable stature to replace Yamamoto. To be safe, he and Layton concocted a cover story: that Australian coastwatchers hiding in the jungles of Rabaul had tipped them off.

Nimitz ordered Admiral William F. Halsey, commanding the area of operations that included Guadalcanal, to get Yamamoto. Like Nimitz, Halsey was concerned the mission would endanger their code-breaking secrets. Nimitz said he would assume responsibility for the risk and suggested that every effort “be made to make the operation appear fortuitous. Best of luck and good hunting.” Halsey’s headquarters transmitted the order: “Talleyho. Let’s get the bastard.”

On April 18 at 7:10 a.m., 18 P-38s took off from the Fighter II airstrip on Guadalcanal. Each twin-boom fighter was fitted with external fuel tanks to extend its range to over 1,000 miles for the mission—made longer by the need to take a circuitous route to avoid Japanese radar. A flat tire on takeoff and a mechanical failure reduced the flight to 16 planes.

Shortly before 10 a.m. near Empress Augusta Bay on Bougainville, the American pilots spotted two Japanese G4M Betty bombers and their escorting A6M Zero fighters. The P-38s’ bullets and cannon shells quickly downed both bombers, and the one carrying Yamamoto crashed into the jungles of Bougainville. One American pilot, Lieutenant Raymond K. Hine, was lost in the ensuing fight. The U.S. Army Air Forces later credited two other pilots—Lieutenant Rex T. Barber and Captain Thomas G. Lanphier Jr.—with the kill.

At every stage, planners had stressed the need for secrecy. But even before the P-38s had landed, security was compromised.

As the returning planes neared Guadalcanal, Lanphier radioed to the control tower: “That son of a bitch will not be dictating any peace terms in the White House.” Lanphier’s announcement was shocking to others on the mission. Air-to-ground messages were broadcast in the clear, and the Japanese monitored American aviation frequencies. Lanphier’s message left little to the imagination. Bystanders on Guadalcanal, including a young navy officer named John F. Kennedy, watched as Lanphier executed a victory roll over the field before landing. “I got him!” Lanphier announced to the crowd after climbing out of his cockpit. “I got that son of a bitch. I got Yamamoto.”

Halsey and Nimitz heard of the success from a secure message, which concluded with: “April 18 seems to be our day.” Halsey jokingly expressed regret, saying he had hoped to give Yamamoto a trip to the White House “up Pennsylvania Avenue in chains.” He passed along his congratulations to the “hunters,” saying it sounded as though “one of the ducks in their bag was a peacock.” When General Douglas MacArthur heard the news, he later wrote, “One could almost hear the rising crescendo of sound from the thousands of glistening white skeletons at the bottom of Pearl Harbor.”

Meanwhile, U.S. officials were trying to make it appear as if the attack on Yamamoto had been sheer happenstance. Over the next few weeks, they repeatedly sent P-38s to Balalae to give the impression that the long journey was a regular mission for American fighter patrols. Additionally, American officials made no public statements to suggest they knew that Yamamoto had been killed. Despite their best-laid plans, officials had forgotten to factor in human nature: people talk.

The secret spread quickly on Guadalcanal, a bustling base humming with activity. Servicemen openly discussed the mission’s details, which soon became common knowledge on the island. With men arriving and leaving every day, the truth was impossible to contain. Eventually, the story spread so widely that it became the subject of cocktail party gossip in Washington, leading at least one citizen, concerned at hearing the loose talk about sensitive operational details, to directly call U.S. Army chief of staff General George C. Marshall.

Chatty pilots became the most serious threat to the code-breaking secret. After the successful mission, the two fliers credited with downing Yamamoto—Lanphier and Barber—enjoyed 10 days of leave in New Zealand. The two were golfing with Brigadier General Dean Strother when an Associated Press correspondent, J. Norman Lodge, approached them. The reporter seemed to know a lot about the Yamamoto mission and, using an old reporter’s trick, asked the pilots to just clarify some details. Amazingly, Lanphier and Barber talked candidly and freely about the mission. Although Strother told Lodge to forget about a story because it would never clear the military censors, the reporter was not easily deterred.

On May 11, 1943, Lodge filed his story with the censors for transmission back home. Although he did not mention the breaking of Japanese codes, he wrote that American “intelligence had trailed Yamamoto for five days” and that American pilots had specifically targeted him. The story included Lanphier’s description of the mission and quoted Strother as saying that the U.S. military had known Yamamoto’s itinerary.

If Lodge’s story had seen the light of day, the JN-25 code might have quickly become a thing of the past. Not only did his story show that the United States knew of Yamamoto’s death, which Japan had not announced, but also that the Americans had known Yamamoto’s location. No Australian coastwatcher would have known his precise schedule; a compromised JN-25 code was the only explanation.

The censors could not believe what they read. They quickly passed the story up the chain of command. Nimitz immediately ordered Halsey to “secure and seal in safe” Lodge’s notes and story. He told Halsey to “initiate immediate corrective measures and take disciplinary action as warranted.”

Lanphier, Barber, and Strother returned from leave to find a summons to meet Halsey on his flagship. When they arrived, an irate Halsey refused to return their salutes and simply stared at them. When he finally erupted, the bombastic Halsey outdid himself. As Barber recalled:

He started in on a tirade of profanity the like of which I had never heard before. He accused us of everything he could think of from being traitors to our country to being so stupid that we had no right to wear the American uniform. He said we were horrible examples of pilots of the Army Air Force, that we should be court-martialed, reduced to privates, and jailed for talking to Lodge about the Yamamoto mission.

Halsey’s bark was worse than his bite; he simply reduced their Medal of Honor recommendations to the second-highest valor award, Navy Crosses.

On May 21, 1943, just over a month after the mission, Japan announced that Yamamoto had met a “gallant death on a war plane” while “engaged in combat with the enemy.” It was front-page news in the United States.

American officials kept up their façade about not knowing what had happened. The U.S. Office of War Information told reporters it thought Yamamoto had been killed in a passenger plane crash between Bangkok and Singapore on April 7, 1943. Other news accounts claimed he might have taken his own life because of recent Japanese setbacks. Reporters flocked to the White House, and the president’s reaction suggested the news was anything but a surprise. “Is he dead?” Roosevelt asked, “Gosh!” The president joined in the ensuing laughter, and all that was missing was a wink and a nod.

Then, two magazine articles poked holes in the American cover story.

The May 31, 1943, issue of Time magazine included a story on Yamamoto’s death. It ended with: “When the name of the man who killed Admiral Yamamoto is released, the U.S. will have a new hero.” That was incompatible with an accidental plane crash or suicide. In that same issue, another story described a mission in the South Pacific that mirrored Operation Vengeance. Although the story did not explicitly name Yamamoto, it described Lanphier shooting down a bomber and, on the way home, wondering if he “had nailed some Jap bigwig.” The implication was clear: the United States knew its fliers killed Yamamoto.

Loose talk about the mission continued and was so prevalent that General Marshall wanted to make an example of any officer caught talking about it. That officer happened to be Major General Alexander M. Patch, who had recently returned from Guadalcanal and subsequently discussed the mission at the Washington Press Club. Patch told Marshall that he “was unaware or unconscious that there was any further need for absolute secrecy regarding an enterprise which had occurred many weeks previously.” Marshall was amazed and angry that “a secret so dangerous to our interests should be publicly discussed.” Marshall was powerless, however, because disciplining an officer of Patch’s rank would have attracted more attention to the story and made matters worse.

The publicity endangered not only the code-breaking secret but also Lanphier’s family. In late August 1943, Lanphier’s younger brother, Charles, was captured when his F4U-1 Corsair went down near Bougainville. As Halsey later wrote, if the Japanese “learned who had shot down Yamamoto, what they might have done to the brother is something I prefer not to think about.” Charles Lanphier died in captivity—without the Japanese realizing what his brother had done.

Despite all these missteps and close calls, the United States’ code-breaking secret held until the end of the war, and decoded messages continued to supply targets for American submarines, planes, and ships. “Despite temporary setbacks as a result of the Japanese introducing new additives or code books,” wrote Commander Layton, Nimitz’s chief intelligence officer, “there was never a sustained period when we were not able to read communications in the principal JN-25 operational system.”

The story behind Operation Vengeance became public less than two weeks after Japan’s formal surrender. “Yamamoto Death In Air Ambush Result of Breaking Foe’s Code,” blared a headline in the New York Times on September 10, 1945. The story, written by an Associated Press reporter, credited fellow reporter Lodge as the source for stating that Yamamoto had “met flaming death…because this country broke a Japanese code.” American fliers, the Associated Press reported, “knew in advance the course his aerial convoy was to follow and ambushed him.” Two years after he initially filed his story with the censors, Lodge finally had his scoop.

Even though the war was over, the navy was still upset by the story. Its officers were debriefing a high-level Japanese intelligence officer who had provided them with valuable information. The naval officers planned to interview other captured officers, too, but feared the code-breaking revelation might shame the Japanese officer into drastic action. “[W]e do not want him or any of our other promising prospects to commit suicide until after next week when we expect to have milked them dry,” radioed a navy officer based in Yokohama.

An exasperated navy department sent back a memorable reply:

Your lineal position on the list of those who are embarrassed by the Yamamoto story is five thousand six hundred ninety two. All of the people over whose dead bodies the story was going to be published have been buried. All possible schemes to localize the damage have been considered but none appears workable. Suggest that only course for you is to deny knowledge of the story and say you do not understand how such a fantastic tale could have been invented. This might keep your friend happy until suicide time next week, which is about all that can be expected.

The question remains: why didn’t the Japanese follow the clues and realize that their JN-25 code had been compromised? In retrospect, it is incomprehensible. Otis Cary, an American navy officer who debriefed Japanese naval officers after the war, wrote that while the Japanese suspected Yamamoto had been ambushed, they “never seemed to have considered seriously that we might be breaking their secret codes.” It is almost impossible to believe that if the shoe was on the other foot, American or British intelligence would not have figured out what had happened. It remains one of the great and enduring puzzles of the

Pacific War.

Historian Donald A. Davis, author of Lightning Strike—an absorbing account of the Yamamoto mission—suggests the reason was hubris. The flaw, he wrote, was not in the code itself, “but in the arrogant and incredibly naïve Japanese belief that Western minds could not possibly understand the intricacies of their complex language, particularly when it was wrapped in dense codes. Despite all of the clues, hubris had overtaken them, and they were unwilling to accept the logical truth that their code was worthless.”

It was a flaw that cost Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto his life and hastened Japan’s defeat. ✯

To wartime America, Isoroku Yamamoto personified Japanese treachery and arrogance because of the attack on Pearl Harbor and his alleged boast that he would dictate peace terms at the White House. He was, however, a man of many dimensions. With his death, the United States lost an enemy who, had he lived, might have become a valuable ally in helping to bring the Pacific War to a quicker resolution.

Yamamoto knew the United States well. He had studied economics at Harvard and had served as a naval attaché in Washington, where he became an avid poker player and socialized with some of the U.S. Navy officers he would later fight against. He was fluent in English and an admirer of Abraham Lincoln. He had traveled in the United States more widely than most Americans. He appreciated America’s potential might, having seen Detroit’s automobile factories, Pittsburgh’s steel mills, the wheat fields of the Midwest, and the Texas oil fields. He had been outspoken in opposing war with the United States and Japan’s alliance with Germany and Italy, earning death threats and the enmity of Japanese nationalists, who called him a traitor and pro-American.

Above all, he was a realist who knew that Japan, with its limited resources, could not stand toe-to-toe with the United States in a prolonged war. Three months before Pearl Harbor, he predicted that if war came, “I will run wild, and I will show you an uninterrupted succession of victories” for the first six to 12 months. After that, he admitted, “I have no confidence in our ultimate victory.” Instead of war, he urged continued diplomatic negotiations with the United States.

Some American intelligence officials thought that killing Yamamoto was a serious blunder since the Japanese war cabinet would never admit that the war was lost. With his realistic outlook, his status as a national hero, and his high standing with Emperor Hirohito, they felt that Yamamoto might have been the one man who could have persuaded the emperor to end the war before it became the to-the-death struggle it eventually was. That would have saved the thousands of lives that were lost after Japan’s defeat had become a fait accompli, but any chance for achieving earlier peace died along with Yamamoto.

Yamamoto’s boast about dictating peace terms at the White House was in fact the work of Japanese propagandists seeking to rub salt in America’s wounds. In a letter to a friend, Yamamoto had written that a war against the United States would not be easy because that country would fight long and hard:

It is not enough that we should take Guam and the Philippines or even Hawaii and San Francisco. We would have to march into Washington and sign the treaty in the White House.

In the afterglow of the Pearl Harbor attack, the Japanese media broadcast an inaccurate and self-serving version:

…I shall not be content merely to capture Guam and the Philippines and occupy Hawaii and San Francisco. I am looking forward to dictating peace to the United States in the White House at Washington.

From that point on, news stories about Yamamoto seldom failed to mention this boast, and stories about his death mocked it. “The Jap who looked forward to dictating peace to the U.S. in the White House is dead,” Time magazine announced. And the New York Times called him the man who bragged of dictating peace terms “from a seat in the White House.”

As for Pearl Harbor, Yamamoto understood America’s capable strength and knew that Japan’s only chance of success was the military equivalent of a first-round knockout. He therefore planned a surprise attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor—immediately following a Japanese declaration of war—that would immobilize the U.S. Navy while Japan seized the territory and resources it desired. Then Yamamoto would lure the remnants of the Pacific Fleet into a decisive battle, which would force a defeated United States to the peace table.

The admiral was so convinced that his plan was correct that he threatened to resign if his superiors did not approve it.

Yamamoto saw the irony in an anti-war admiral planning the attack that would start the war. “I find my present position extremely odd,” he wrote, “obliged to make up my mind and pursue unswervingly a course that is precisely the opposite of my personal views.”

The Japanese government planned to break off all negotiations with the United States before—but only minutes before—the first bomb fell on Pearl Harbor. According to historian Gordon W. Prange, it was “strictly a formalistic bow toward the conventions.”

Ambassador Kichisaburo Nomura was told to deliver to Secretary of State Cordell Hull a message breaking off negotiations promptly at 1 p.m. on December 7, 1941 (8 a.m. Hawaiian time). Because of delays in decoding and typing the message, however, Nomura did not arrive at the State Department until 2:05 p.m. (9:05 a.m. Hawaiian time). By then, the Pearl Harbor attack was under way.

Even if delivered on time, Nomura’s message would not have given the United States fair notice of war. The message did not declare war or even break off diplomatic relations. It simply ended negotiations. Japan did not formally declare war until hours after the attack. The Japanese Foreign Ministry had prepared a clearly worded declaration of war before the attack but chose not to have it delivered to Secretary Hull.

The inescapable conclusion is gamesmanship. The Japanese government wanted to orchestrate the attack so that it could receive the tactical benefits of a sneak attack but still be able to later deny that it was, in fact, a sneak attack.

How much Yamamoto knew of this gamesmanship still remains an open question. Cary, the navy officer who debriefed high-level Japanese naval officers shortly after the war, believed that the Japanese government had kept Yamamoto and the Japanese navy in the dark:

It had never occurred to the men I talked with that the plan was laid around the fact that the attack was going to take place before war had been declared. Certainly Admiral Yamamoto had not conceived of it as that, although he had made the decision that Hawaii would have to be attacked.

Yamamoto’s actions support this viewpoint. The weak resistance to the Pearl Harbor attack led him to suspect that the attack had come before a declaration of war. He asked an aide to investigate because, he said, “there’d be trouble if someone slipped up and people said it was a sneak attack.”

Yamamoto knew how the United States would react, and he was right. It was a sneak attack, and it did lead to trouble—trouble that ended in his death in the skies over Bougainville.

—Joseph Connor

[hr]

This story was originally published in the January/February 2017 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.