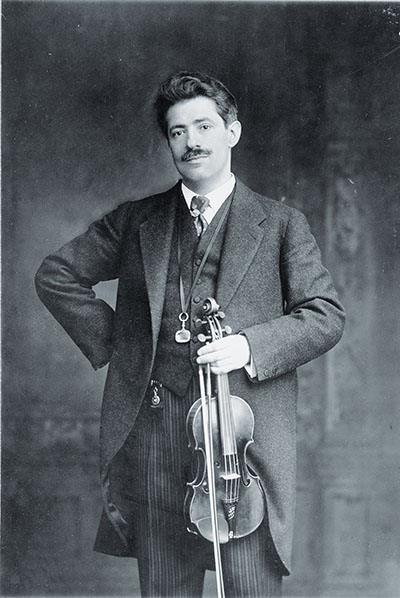

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]s Fritz Kreisler stepped onstage at Cornell University’s Bailey Hall the evening of Thursday, December 11, 1919, the Austrian-born violinist was on edge. Kreisler was making his first American tour since an armistice ended the Great War exactly 13 months before. A show at Carnegie Hall in Manhattan had gone smoothly, but now he was in the hinterlands, where hatred of all things German spurred by the war had led to mob violence and at least one lynching. Despite the return of peace, anti-German sentiment still reigned throughout much of the United States. “He stands for the principles of Prussianism and Kultur,” an Ithaca newspaper wrote in advance of the Viennese virtuoso’s Cornell concert.

Kreisler, 44, initially gained fame in America as a 12-year-old musical prodigy and toured the country successfully as a young performer. In 1902, he married American tobacco heiress Harriet Lies. A reserve officer in the Austro-Hungarian Army, he was wounded on the Russian front, decorated, and honorably discharged

in September 1914. He and Harriet left Europe for the

United States, where they would spend the duration. Kreisler eventually withdrew from public life because, after President Woodrow Wilson declared war on Germany in April 1917, many Americans declared war on their fellow citizens and residents of German descent.

Germans had been among the earliest and most enthusiastic immigrants. In 1683, Francis Daniel Pastorius founded Germantown on 15,000 acres of what would become Pennsylvania. So many German speakers and readers were living in that state as the Constitution was being ratified that of 3,000 copies printed for popular review, 1,000 were in German (see “Beware the Bruisers,” p. 16). In the 1800s, waves of Germans settled in locales as disparate as East Texas and the Upper East Side of Manhattan. German-Americans introduced their adoptive homeland to the accordion, the pickled cabbage dish called sauerkraut, the sausage on a bun that became known as the hot dog, and of course the German approach to brewing beer. Beer gardens, singing groups called Liederkranzen, and acrobatic teams called Turnvereine were features of heavily German neighborhoods like Over the Rhine in Cincinnati, Ohio, and Yorkville in New York City. Most German immigrants were farmers or skilled artisans. At times, envious nativist ire at the industrious newcomers boiled over into violence, such as mid-19th century anti-German rampages by mobs in Louisville, Kentucky.

In 1850, German was America’s second most popular language. President Abraham Lincoln’s first official act in the White House in 1861 was to hire a secretary fluent in the tongue to correspond with citizens and 80 German-American newspapers. About 178,000 Germans fought in the Civil War, more than any other foreign-born ethnic group; the Union Army had 18 German-speaking regiments. A survey of Western governors by the Harvard-based Immigration Restriction League showed Germans to be the least resented immigrants “because they all work.” By 1900, seven million Germans had immigrated to the United States. In the 1910 census, 2.3 million Americans were German-born and about 10 million claimed to be of German descent.

But none of that counted when America went to war against the kaiser, and even before that anti-German propaganda from Britain was priming the pump for resentment and worse. Anger intensified in 1915, when a German torpedo sank the British liner Lusitania, drowning 128 American passengers. Rumor blamed German agents for a gigantic munitions explosion on July 30, 1916. The blast was known as “Black Tom” for an island, linked by causeway to Jersey City, New Jersey, on which the armaments had been stored.

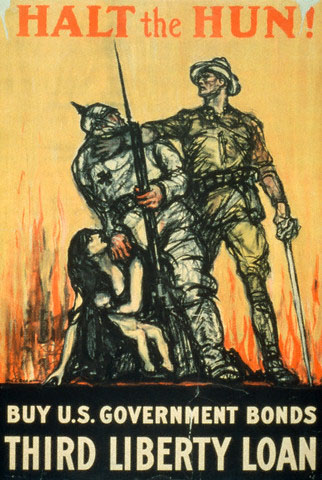

Wilson finally went to war over a German overture offering Mexico and Japan slices of the United States if the Central Powers won the conflict. Now at war with Germany, Americans furious about torpedoes and sabotage vowed to wipe the country free of every trace of German heritage. They renamed dachshunds “liberty pups” and sauerkraut “liberty cabbage.” Kaiser Wilhelm II, once an honored friend of Theodore Roosevelt, became “The Beast of Berlin” and “The Werewolf of Potsdam.” In Germantown, now a Philadelphia suburb, plans for a monument to Francis Daniel Pastorius were shelved. At Independence Day parades, men dressed as Wilhelm wore nooses for neckties. Rubella had been called “German measles” for a century or more because a German doctor first described the childhood disease in 1740. Now hearsay held that German scientists had concocted rubella and influenza to kill Allied soldiers and children. Official government propaganda posters casting the Germans as ravening beasts implicitly encouraged stateside scorn and for Americans of real or imagined German heritage.

In autumn 1917, American orchestras began opening concerts with “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Boston Symphony music director Karl Muck, born in Germany, had offered to resign when the United States entered the war in April, but management signed him to another five-year contract. The symphony was to perform at Infantry Hall in Providence, Rhode Island, on October 17, 1917. “Professor Muck is a man of notoriously pro-German sympathies,” John R. Rathom, editor and publisher of the Providence Journal, wrote in advance of the concert. “The programme as announced is almost entirely German in character.” When the performance did not include the national anthem, Rathom called out Muck as a spy and a hater of all things American. The American Defense Society, seconded by former President Theodore Roosevelt, demanded the government intern Muck. “Does the public think that the Symphony Orchestra is a military band or a ballroom orchestra?” Muck defiantly asked. But he began to add “The Star-Spangled Banner” to every show.

On March 25, 1918, federal agents arrested Muck at his home in Boston and, with Boston police officers, ransacked the place. They found musical scores annotated with what officers thought to be coded messages. Symphony founder and sponsor Henry Lee Higginson resigned in protest, taking with him much of the orchestra’s financial support. Federal officials deported Muck in August 1919.

“I am not a German, although they said I was,” Muck told reporters. “I considered myself an American.”

In areas where German surnames proliferated, rancor took more violent form, prompting citizens with obviously Teutonic monikers to make them less Old World–sounding; a name like “Drumpf,” for example, might become “Trump.” Propelling such gestures were episodes like one involving Robert Paul Prager, who had left Dresden, Germany, in 1905 for the United States. Prager was a drifter scraping by in St. Louis, Missouri, when the United States declared war on Germany. The U.S. Navy rejected him because he had a glass eye. The United Mine Workers Union refused to issue the immigrant a union card because he was a German, “unmarried, stubbornly argumentative, given to Socialist doctrines, blind in one eye and looked like a spy.”

On April 5, 1918, in nearby Collinsville, Illinois, police saw a mob parading Prager around waving a tiny American flag in each hand. An officer took the beleaguered man into protective custody. The mob stormed the jail, overpowered policemen, and marched Prager barefoot through the streets wrapped in an American flag. He begged for mercy and wrote a note in poor German: “Dear parents! I must today 4-4-18 die please pray for me my dear parents that is my last letter to show my love for you. Your loving son and brother Robt Paul.” After Prager had knelt and prayed, the mob of 200 to 400, which included more than one man with a Teutonic last name, lynched its captive from a telephone pole. “Well, I guess nobody can say we’re not loyal now,” a farmer said. “German Enemy of U.S. Hanged by Mob,” read a headline in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat. “This is the first killing for disloyalty in the United States, although many persons have been mobbed and tarred and feathered,” the paper reported in a story that included other outrages: “On March 22, four men, including a Polish Catholic priest, were tarred and feathered at Christopher Ill., a mining town eighty miles from St. Louis.” Authorities arrested 11 suspects, whose defense lawyer argued that the police had failed to protect the community. A jury exonerated the accused men.

Some state governments brought harsh pressure onto German-Americans. Minnesota legislators voted in April 1917 to set up a Commission of Public Safety, headed by Gov. A.A. Burnquist, to investigate and punish disloyalty. In June, that body went after New Ulm’s mayor and city attorney, both of German descent, for convening a meeting to discuss the draft’s legality. The mayor, a physician, lost his medical license. The committee also forced the resignation of Adolph Ackermann, president of Luther College, for questioning government motives for entering the war and pressured police to arrest newspaper editor Albert Steinhauser for criticizing the war in the New Ulm Post and New Ulm Review. Federal authorities in Minnesota jailed editor Frederick Bergmeier of the St. Paul–based German-language daily Tägliche Volkszeitung until after the November 11, 1918, armistice.

As American casualties mounted in Europe, violence struck in areas with large German populations. On June 19, 1918, John Meints, a German-American farmer in Luverne, Minnesota, was kidnapped by a mob from his house to Iowa, accused of not supporting war bond drives. The farmer reported the abduction to the U.S. Justice Department; officials told him it was safe to return home. On August 19, a mob found Meints living with one of his grown sons and dragged him across the border into South Dakota, where men beat,

whipped, tarred, and feathered him. His assailants threatened Meints with lynching if he returned to Minnesota, but he did go home and sued 32 individuals he could identify for false imprisonment, demanding $100,000 in damages. The U.S. District Court found against Meints, ruling that he was disloyal. Citizens of Luverne welcomed the members of the tar-and-feather mob with a brass band. Meints appealed the verdict and settled out of court for $6,000 in 1922.

Deeper American engagement in France had its parallel in abuse in America. On October 22, 1918, John Deml of Outagamie County, Wisconsin, heard his wife say that men on their porch wanted to see him. The seven carloads of visitors, including neighbors, pushed into the house and demanded that Deml buy more war bonds. He said he had signed up for $450 worth. The men claimed his share was $800, punched him, and put a rope around his neck.

“I will not sign up for any man after being abused like this,” Deml said. The men left when he agreed to buy more bonds.

Out of the instinct for self-preservation, some German-Americans reached beyond denaturing their family names to recasting themselves as Norwegian, Swedish, Swiss, or Dutch. Some gave children Anglo-Saxon names like Donald or Malcolm and dressed them in plaid. Liederkranz societies dwindled. Turnverein halls were rented out for high school reunions and other events. Classical music, so often associated with German composers, became less popular in America than in any other country. Even if they kept their names, German-Americans kept their heritages to themselves, assuming the role of American super-patriots.

“My mother and her sister used to talk over the telephone and they’d talk in German, and of course that would ire the English or the other people, they didn’t like it and they’d slam the receivers down. But they overcame it, after two or three years it all straightened out. And everybody was associating again” said Fred Brocke, an Idaho farmer and later a bank president. ”There was a lot of hatred against the Germans and if you were German, you were a little bit tainted, I guess. But, as I said, [if you] minded your own business, you didn’t go looking for trouble….We had no particular argument with anybody, and of course you got along.”

But going along to get along only went so far, and feelings ran hard and high until well after the Allies defeated the Central Powers. In 1917, Civil War veterans, the Daughters of 1812, and the Daughters of the American Revolution denounced Fritz Kreisler. Sophisticated audiences in New York and Philadelphia applauded his musicianship, but small-town bookings withered. Kreisler largely suspended his solo career to live with Harriet in Maine, playing in an ensemble and donating to war-related American charities.

Harsh attitudes to things German persisted into peacetime, gradually ebbing—first in cities, then in the countryside. In October 1919, the month the American Legion, a veterans group, denounced German and Austrian performers and German opera, Kreisler made his first stage appearance in years. He brought a capacity crowd at Carnegie Hall to its feet for a five-minute ovation. The same tour brought him to Ithaca on December 11, 1919, with burly young men filling the entire front row of Cornell’s Bailey Hall. Kreisler, playing with verve and his world-famous vibrato, offered up Liebesfreud (“Love’s Joy”), Liebesleid (“Love’s Sorrow”), and Schön Rösmarin (“Beautiful Rosemary”).

Someone suddenly cut the lights. About 80 American Legionnaires charged the stage to find that the front row was filled with Cornell football players who meant for Kreisler to perform. A brawl began, with the athletes joined by Cornell bandsmen and spectators from a basketball game. The legionnaires never reached the stage, and Kreisler concluded with Viotti’s “Concert in A Minor,” not missing a note despite playing in total darkness.✯

This story was originally published in the July/August 2016 issue of American History magazine. Subscribe here.