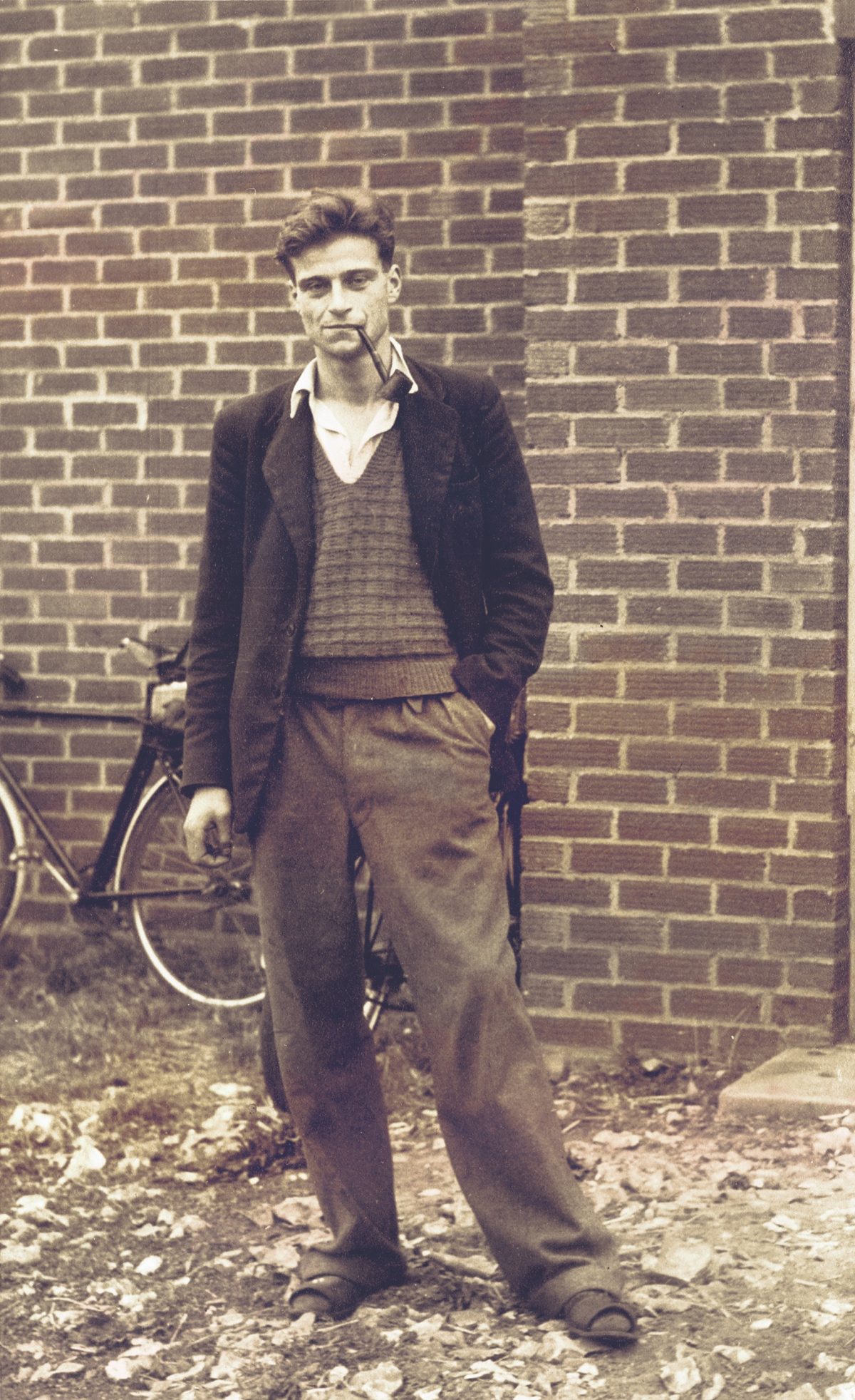

Born in Manchester, England, in 1914, Harry Rée was the son of an industrial chemist from a Jewish family and an American-born heiress to the du Pont chemical fortune. As a student at Cambridge University in the 1930s, he signed the Peace Pledge, but after visiting his Jewish cousins in Germany he became preoccupied with Adolf Hitler and the menace of Nazism. In June 1940, following the fall of France, he gave up a promising teaching career to enlist in the British Army. A year later he was recruited into the F (for France) Section of the Special Operations Executive, and in April 1943, after intensive training, he parachuted into France. There, using the code name César, he guided various resistance groups in a series of dramatic sabotage operations against railways, canals, warehouses, power stations, and factories. At one point he got into a hand-to-hand fight with an armed officer of the German military police, but he somehow managed to escape despite having been shot four times. After returning to England in 1944, Rée received the Distinguished Service Order, among other British and French honors, as well as the French Médaille de Résistance Française and Croix de Guerre. Three years later he starred in Now It Can Be Told, a government-produced film based on his activities as an SOE agent in France.

After the war Rée resumed his career as an educator. He occasionally appeared on Brains Trust, a BBC program in which a panel of five experts tried to answer questions submitted by audience members. He died in 1991 at age 76.

The following narrative is adapted from A Schoolmaster’s War: Harry Rée, British Agent in the French Resistance (Yale University Press, 2020), a collection of Rée’s war writings edited by his son, Jonathan Rée, a freelance historian and philosopher.

It was a beautiful morning for a murder—a fine, sunny morning in July 1943, and I looked out of my bedroom window in the hotel over the green plateau, where the cow-bells were jangling; the sound drifted across the fields with the breeze. It was more than a breeze, really. At that time in the morning it was a cold wind, carrying with it still the memories of the snow-covered peaks of the Alps. What a ridiculous position I had got myself into. Here was I, a British officer, tying my tie in the upper bedroom of a French hotel, all prepared to kill a man after breakfast. In my bag was a revolver and a piece of rubber hosepipe stuffed with thick wire—a home-made “life-preserver” (incongruous word). I hoped to be able to hit him over the head with it first so that I could then kill him at my leisure, quietly.

You see, he was a traitor, this man, Pierre Martin, whom I was going to kill, and he was very dangerous. I had met him for the first time three months before. He had been introduced to me as a man who would be useful for transporting arms and explosives from our dumps in the countryside into the town of Dijon. He had a delivery van and he proved to be extremely effective. And at our very first meeting I took a liking to him. He had done six months in Dijon prison—arrested in 1941, suspected of helping British airmen to escape from occupied to unoccupied France. He was a big, cheerful man, with a kind smile. I got on very well with him. We both wanted to get on with the job, and we both liked good food and good wine. But if it were a question of one or the other—we would leave the food and the wine and get on with what had to be done.

I remember the first job I did with him. We worked all night, climbing up to a cave in the side of a mountain to collect a dozen metal bins of arms and explosives. Shortly after midnight we parked the van just off the road and climbed for half an hour to this cave. Once inside the cave we were able to light torches, and we went clattering down the wet, black, flinty tunnels to the dump. We could only carry one bin at a time and it was a tricky business. The path down the mountain led through woods and across streams. It was steep and slippery. We had to make three journeys. By three in the morning we had finished and, as we did not want to set off for Dijon until it got light, I suggested we go into a nearby barn for some sleep. Pierre agreed and collected a bag from the van. We went into the barn: lovely smell of old hay. We lay down and good old Pierre opened his bag and brought out a long, crisp loaf and a hunk of local cheese and a bottle of wine. We shared the meal and topped it off with some brandy from his flask. Then we made ourselves comfortable in the hay and went to sleep till morning. By next evening the arms were stored away in a cellar in Dijon.

Then I began to hear stories about Pierre from other Frenchmen who were working with me: stories that did not reflect too well on his character. He had been in the motor trade before the war and evidently had a reputation as a swindler. He had a wife and four children, but he was not living at home and he neglected them. He would be quite prepared to spend a thousand francs on a meal for himself, but he begrudged sending five hundred francs to his wife to pay the rent. But we knew we should not believe all the stories we heard about other people and Pierre continued to work very satisfactorily. Then one day in the middle of July he went out of Dijon in a taxi with another British officer, John Starr (“Bob”). They were going to look for a suitable reception ground—a well concealed field where aeroplanes from England could come and drop arms by parachute. Just before they left, Pierre said he had a telephone call to make. He went away and came back five minutes later. Five miles out of Dijon the taxi was stopped by the Germans. Pierre and Bob were arrested and taken to the Gestapo prison. Pierre was released the same afternoon, but Bob was kept in prison. I heard about it two days later in a note I got from Pierre himself: “Dear Henri, Can’t understand how they got me and Bob, nor why they released me and not Bob. Are you being followed? Take great care. Meet me Friday afternoon in the waiting room of Dijon station. Yours, Pierre.”

To cut the story short, I did not, of course, go to the waiting room. [A] boy in the cafe told me that all the Dijon group were against Pierre now. They realised he was a member of the Gestapo and they planned to kill him that Sunday, as Pierre was still pretending to be working with them. But that plan failed and within a week ten of them had been arrested. Then other people known to Pierre in other towns were arrested. One young man, a very dashing French officer called André Jeanney, said he’d get him. They met in a little village and talked about the future, because Pierre, as I said, still pretended to be working with us in the Resistance. André wanted to shoot him there and then but there were too many people about. So he hit on this plan. He told Pierre that I was losing my nerve with all these arrests going on, that I had retired to a little farm on the French side of the Swiss frontier, so as to be ready to run into Switzerland at the first sign of danger, and that I was proposing to hand over my organization to Pierre. So André suggested that Pierre should come up to a little town near the frontier called Maîche, and André would meet him there, and guide him to my hideout. There we would discuss the details of handing over the organisation. Pierre agreed.

I must say when I heard it I didn’t think much of the plan. But I couldn’t possibly back out: you see, I couldn’t afford to lose face, and anyhow I didn’t want to miss an opportunity of getting rid of Pierre. It was my duty to see that he was put out of the way.

The details of the plan were as follows: André and I would go up to Maîche the day before the rendezvous. We would stay the night in an hotel, like ordinary holidaymakers, and the following morning we would set off for a little clearing in the woods which André had known since he was a boy. He would leave me there, go and fetch Pierre at the rendezvous, and explain to him on the way that I had come halfway to meet them, and that we would have our confab in the woods. He would bring Pierre to me, then in the middle of the confab I was to hit the unsuspecting Pierre over the head with our homemade cosh. If that worked we would muffle the pistol and shoot him, and carry his body to a disused well in the woods and throw him down. If it didn’t work, we would just have to shoot it out. Two against one, with surprise on our side—we ought to be pretty safe. And once down that well, the body would never be found.

There I was, then, tying my tie in the hotel bedroom in Maîche. André was still asleep. After stuffing my pistol and cosh in my trouser pockets, I woke him up and went down to have some breakfast on the terrace in the sun.

I looked round at the French holidaymakers having their breakfast. There was a mother and father and three young children planning a picnic. I wonder if all murderers look around at people in restaurants or trams and say to themselves: what would these people say if they knew? I dare say they do. I have heard people who were doing secret jobs in the war confessing that they used to chortle to themselves in trains to think that they knew the date of D-Day, or the destination of that night’s bombing raid, and no one else in the carriage did. I suppose it’s just a harmless way of inflating one’s self-esteem. Anyhow, I know that I indulged in it that morning. My self-esteem needed some inflating. I didn’t at all like the idea of doing this killing. André joined me at breakfast, and we chatted about the weather, and the possibilities of coming to the hotel in winter for a season of skiing. After breakfast we paid our bills. I wonder why we paid our bills? We had no intention of ever returning to that hotel. It had not occurred to me that murderers might be honest men. Anyway, we paid and set off out of the town on our bicycles.

The road went down, through woods, from the high plateau. Ten minutes cycling, and André cut off to the right, up a lane. It got too rutty so we got off and pushed our bicycles. Then we turned off again, up a grassy path. After two hundred yards the path opened out into a little glade. There was a tumbledown woodman’s cottage on the right—deserted, and with no roof. Just outside the cottage door was a well.

We stopped there and made our final plans. We decided that when André came back with Pierre, he would warn me by whistling the first two phrases of a French song—you probably know it—called “je tire ma révérence.” If all was well, and Pierre was unsuspecting, he would whistle these two phrases. If something had gone wrong, he would just whistle the first phrase.

André then left to go back to Maîche; he was meeting Pierre in a cafe there at ten o’clock. When he had gone I began to wander about. I explored the deserted cottage and looked down the well. I dropped a brick down and timed its fall with my watch. It took between two and three seconds. I tried to work out how many feet that was, but I had forgotten the formula. It was no good—nothing would stop me thinking about what I was about to commit. What right had I, a living creature, to take the life of another living creature? I, an Englishman, to take the life of a Frenchman? Logically, of course, it was war. I was doing it in self-defence. If I did not kill him, he would get me arrested by the Gestapo, tortured, then probably shot. Yes, I was doing it in self-defence, but it was not at all the sort of situation a soldier finds himself in when he shoots an enemy soldier who is trying to shoot him. This was cool and calculated…there is that word coming at me again—this was cool and calculated murder. Why should I be frightened of a word? I had to persuade myself that the deed I was going to do should be called by some other name.

I thought up all the arguments I could against Pierre. He was a swindler and a cheat, and he would be of no value to France or society after the war—but who was I to judge him? What would the Lord Chief Justice say to that kind of argument? What would the Manchester Guardian say, for instance? I began thinking about C. E. Montague’s novel Rough Justice (1926) about the last war. Revenge is a kind of “rough justice.” This act I was going to commit was revenge—revenge for Bob (John Starr) and for the dozens of French people Pierre had betrayed in the past few weeks; and what I was going to do was rough justice. Having reached that stage in the argument with myself, I was able to lie back in the dewy grass and watch the sunlight filtering through the trees and even listen calmly to the birds.

And then I heard a crackle of twigs—footsteps approaching. I was behind the cottage. I could not see the glade. I listened. Something was wrong. André whistled the first phrase but not the second. I came out cautiously, and there was André—alone. He had gone down to the cafe. It was empty, so he sat down and ordered a coffee. Two men had come in, looked at him hard, and sat down at another table. He waited five minutes. A car drew up, a closed car. He recognised the two men who got out of the front seat—they were Gestapo men from Dijon. He got up. He did not pay his bill this time. He left the cafe by a side door, got on his bicycle, and as he swung past the closed car, he recognized Pierre sitting in the back, reading a newspaper.

So our plan had not worked. Pierre had given up playing a double game, he was all out to get us now; in particular, of course, he wanted me. Well, I was lucky. He did not get me. My friend Claude would get him eventually…but that is another story. MHQ

This article appears in the Summer 2020 issue (Vol. 32, No. 4) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Experience | ‘Traitors Must Die.’