On the road year-round, he brought clean-cut entertainment and small-town spectacle to burgs up and down the Lone Star State

On a balmy day in 1928 in a remote Texas town—Muleshoe, maybe, or Sweetwater or Spur or Dickens, perhaps Big Springs, Junction, Eldorado, or Matador, the big state has so many such places—folks from near and far jam either side of Main Street, drawn to the opening fanfare of what promises to be a thrilling week. Along comes a slickly uniformed marching band led by an exuberant fellow whacking a big bass drum, often off the beat, as he smiles and greets onlookers. “Hi Butch, how’s the family? How Ya’ doin’, Mitch?” Harley Sadler calls out. “Mornin’ Millie! George out of college yet?”

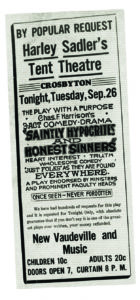

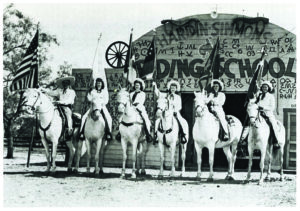

Behind the musicians, brilliantly costumed performers smile and wave to fans. When the procession reaches the town square or the central park, Sadler sets aside his drum and starts his “ballyhoo,” as he calls it, describing the show that will occur at dusk that evening—a panoply of dramatic and comedic sketches, musical interludes, dance troupes, raffles—something for everyone, conveniently staged at the edge of town, and priced at only a quarter for adults and 15 cents for kids. The band plays a few rousing songs. Sadler takes up his drum and leads the ensemble to the big tent. Grownups head for the ticket booth. As always, boys follow, volunteering to set up folding chairs in exchange for admission.

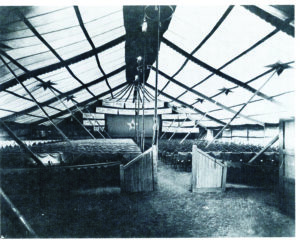

Roustabouts have unpacked and put up the big tent, a huge rectangular canvas affair; above the entry hangs a sign: “The Harley Sadler Show.” Stagehands are making last-minute adjustments as customers queue for a three- or four-act play punctuated by announcements, candy hawkers, and “specialty acts.” The script might be new or a long-time favorite, but always it’s an engaging melodrama leavened by humor and populated by characters familiar to rural audiences. The script is tailored to each locale, mentioning places and events the crowd knows. The specialty acts include child dancers or singers, jugglers, magicians, trained dog acts, and vaudeville comics. More than one customer will be back for more than one performance during the week-long residency.

Sadler is on the road from March to December. When the operation reaches San Angelo, Sadler pauses to throw a Christmas banquet, then proceeds to Sweetwater, his home base, to stow most of the costumes, props, and gear, dusted with black pepper to repel roaches and rats, for the winter. A scaled-down edition of the production plays theaters in Waco and other towns until spring, when the circuit calls again, resuming the two-year schedule of bookings that brings most of West Texas and eastern New Mexico a heaping dose of spangles and glamour and show-business excitement.

The tent show helped forge the character and content of American theater. Immensely popular from the 1850s through the 1920s, the phenomenon survives today as a phrase in a classic-rock oldie, but in its heyday no amusement held Americans in a tighter grip. Beneath the rubric of the traveling tent show gather circuses, medicine shows, Chautauqua gatherings, and such, but one subspecies was traveling tent theater, or “rag opries.” In 1927 The New York Times counted 400-some tent-theater troupes nationwide, annually reaching audiences of 76 million at a time when mainstream playhouses were drawing 48 million theatergoers a year.

A typical tent show worked towns of 10,000 or fewer, setting up for a week or two to the delight of residents who otherwise had scant access to big-bore entertainment. The two-to-three-hour program of skits, playlets, and comic sketches took place under canvas, sometimes before 2,000 or more spectators on chairs or bleachers. Tent theater had its zenith in the years preceding Black Tuesday—October 29, 1929, when Wall Street crashed, triggered a depression that, along with radio, talking pictures, and increased personal mobility, doomed the traveling show. While the good times lasted, though, Harley Sadler was America’s tent show king.

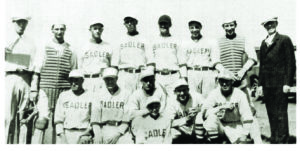

Born in 1892 in Pleasant Plains, Arkansas, Harley Sadler arrived after brothers Luther, Edgar, and Leonard. Junius E. and Lula T. Sadler soon moved their boys to Texas, where they tried and failed to farm at several locations. In 1905, Junius quit the harrow and the plow to open a general store in Stamford, near Abilene. By that time, there were two more Sadler children, daughter Fanny and Ferdinand, called Ferd. As a youth Harley worked for his dad and held other part-time jobs. At school, he played trombone, acted, and made the baseball team. In 1909, intent on a life in show business, he ran away from home to join the Houston-based Parker Brothers Carnival as a trombonist but wound up hawking candy and popcorn. He soon returned home, recruiting two pals into a vaudeville act that made it as far as Kansas City before the other fellows dropped out.

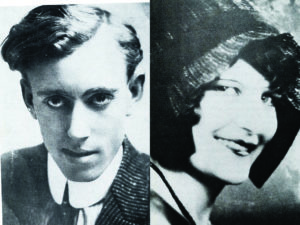

Harley remained on the road, taking show-related jobs like posting promotional flyers, sometimes for traveling shows like Roy E. Fox’s Popular Players. His folks moved to Avoca, Texas, and opened another store. Illness brought Harley home. He opened a tailor shop and tried studying law on the side, but a traveling show caught his attention. He hired on with the troupe, hopscotching the region acting, singing, and telling jokes. Laughs became his stock in trade. In late 1914, Roy E. Fox hired him, and Harley Sadler settled into professional show business life, progressing to second and then first banana on an appearance in Avoca, wowing the crowd but prompting his mother to ask when he was going to get a job. A few days later, in Cameron, Texas, Sadler met and eloped with Willie Louise “Billie” Massengale. Harley won over his shocked in-laws and hopped from Fox to the Glen Brunk Company as its principal comedian and stage manager, making a better salary while acquiring more managerial experience—especially when, in 1917, Brunk was drafted to serve in the American Expeditionary Forces fighting in Europe. Onstage Sadler delighted audiences; backstage he kept the operation profitable. By the time Brunk mustered out, Sadler had decided to go out on his own. In an amicable split, he left Brunk’s employ and at the end of December 1921 began organizing “Harley Sadler’s Own Show” as he and Billie prepared for the birth of a child. Gloria Sadler, named for actress Gloria Swanson, arrived at home in Cameron, Texas, on March 10. Harley and troupe began performing that month, with Billie, babe in arms, soon joining the outfit.

Traveling by rail through the 1920s, the show had its own gaily painted promotional baggage and coach cars. The entourage timed arrivals for Monday mornings, met by local draymen who moved the show’s components to the lot it would occupy. “From the baggage car spilled forth heavy bundles of canvas, poles, coiled ropes, stakes, marquee, lights, wardrobe, bleachers, chairs, scenery, ticket booth, stage platforming, curtains,” Sadler biographers Clifford Ashby and Suzanne DePauw May wrote in Trouping Through Texas. The tent could seat about 2000. The raised stage spanned 30 feet, with dressing rooms at either side and an orchestra platform for holding 12 to 15 bandsmen.

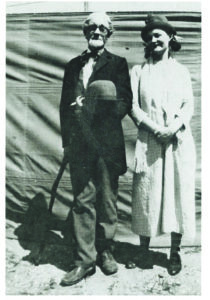

As in most tent shows, Sadler brought his entire family in on the action. Billie acted in skits, sold tickets, helped with costuming, and filled in as needed.

As in most tent shows, Sadler brought his entire family in on the action. Billie acted in skits, sold tickets, helped with costuming, and filled in as needed.

Her brother, Burnie Massengale, was a “canvas man,” overseeing tent work. Mother Louise “Mama Lou” Massengale served as a dresser and seamstress while minding Little Gloria—who also took to show business, as a toddler dancing and singing in specialty acts. Ferd Sadler handled promotion; his wife Gladys sold tickets; their daughters Marie and Toby stayed home during the school year but spent summers with the show as a vaudeville act. Nephews and nieces might be on the payroll. The 50-to-60-member company often included married couples and small family groups, a factor in the stability of crew and cast.

Sadler the entertainer became Sadler the showman, a model impresario adept at memorizing and recalling names and faces, a skill enhanced by a generous, sincere manner. He made sure to support local enterprises and organizations like Rotary clubs. Making a point of attending local church services and civic events, he cultivated friendships at every stop and insisted employees do the same. At all times show staff were to dress neatly and display courtliness—no cursing, no quarreling, no drinking on or off the clock. Shows reflected the values of the folks who filled the stands for entertainment Sadler kept clean and family-oriented.

Working through 60-some stops every two years, Sadler and team developed a rhythm. About three days before the troupe was to hit a town, advance man Ferd Sadler arrived to connect with the local sponsor—an American Legion post, volunteer fire department, the Lions’ Club—which in exchange for 10 percent of ticket sales arranged a tent site. Ferd called on retailers, distributing passes in exchange for displaying posters. Here getting a shave, there patronizing a café, glad-handing the newspaper editor, Ferd left a trail of goodwill and free and paid advertising.

Ferd’s checklist included churches, civic organizations, the mayor’s and sheriff’s offices, fire and police department, and so on, distributing passes and offering free performances by troupe members, including Harley Sadler himself. A team of performers might play the local baseball nine. If the town had a furniture store, Ferd paid a visit, asking to borrow props, usually provided gladly, and items to be awarded to raffle winners. As Ferd was finishing his way-straightening, the train pulled in, crews jumped out, and up went the tent, dressing rooms, stage, and bleachers. Show folks donned their glad rags and stepped out in Harley Sadler’s enthusiastic wake to whet the locals’ appetite for an evening of razzle-dazzle.

In most towns, performers and staff roomed at hotels or boarding houses, though as a last resort the dressing rooms could serve as shelter. Sadler’s strict controls on troupe member behavior—violations were generally a firing offense—limited trouble with host towns.

In most towns, performers and staff roomed at hotels or boarding houses, though as a last resort the dressing rooms could serve as shelter. Sadler’s strict controls on troupe member behavior—violations were generally a firing offense—limited trouble with host towns.

Sadler’s library of scripts—in a weeklong residency the troupe staged several—mixed down-home humor and moralizing. The usual performance included a play of three or four acts written by Sadler or a stock tent-show warhorse. One example was Ten Nights in a Barroom, an adaptation of a popular 1854 temperance novel about the evils of drink and a sot’s redemption by his angelic daughter’s deathbed plea. Another Sadler favorite was Honest Sinners and Saintly Hypocrites, a play by Charles Harrison that pitted rural virtue against urban corruption. Sadler adapted scripts and characters to a given crowd and location as well as to his performing style. Audiences most loved his pet character Toby, a genial hayseed, naïve and gullible but in the end usually victorious as an unwitting hero. Toby wore a loud shirt, patched overalls, and broken-heeled, curly-toed boots, all topped by a red wig and a flimsy hat. Besides his footlight turns in the company’s plays, Toby appeared at intermissions to tell stories and hawk candy, drawing wild applause with self-deprecating tales like one about a Wednesday night in Dallas that he and his pa registered at a fancy hotel. The accommodations featured a second room outfitted with a big porcelain tub, fluffy towels, and cold and hot running water. “And me and Paw just stood there looking at it all, wishing it was Saturday night,” Toby said wistfully.

Between acts and during scenery and costume changes, the stage filled with tap or ballet dancers, ballad singers, ventriloquists, magicians, jugglers, harmonica players, or cowboy singers. From age four, Gloria Sadler tap-danced. An actor might step offstage and pick up a band instrument, tootling away in costume. Vendors, including the head Sadler himself, hawked “bally candy,” salt-water taffy rolled and packaged in small boxes. In some boxes were tickets good for prizes ranging from stuffed animals to diamond rings. At the boss’s signal a curtain flew back to reveal the loot, augmented by rocking chairs, radios, cookware, and other items from local merchants. Winners claimed their booty onstage to cheers and applause.

In 1923, Sadler leased the Lyric Theater, a cinema in Sweetwater, to store gear and rehearse; when he went on the road, the Lyric resumed showing movies. In 1927, he bought a lot on James Street and built a tile-roofed brick residence for his extended family. When Gloria began school, she, grandmother Mama Lou, and housekeeper Elnora held the fort while her parents were on the road. Summers through high school Gloria traveled with the show.

The show was an expensive proposition but also a moneymaker, regularly bringing $3500 a week in revenue. By 1929 Sadler was grossing perhaps $150,000 annually. Besides his home and company, he owned farms in three counties and lots he had bought in cities on his tour schedule to guarantee a suitable place for the show to go on. Never careful about money, Sadler was quick with a loan for a friend in need, a trait that often put him in financial trouble. He not only “lent” friends and family money, but strangers telling tales of hardship; busted farmers and townsmen got handshake loans.

By 1930, according to his treasurer, Charles Meyers, Sadler was holding more than $80,000 in unsecured debt owed by parties all over West Texas and Eastern New Mexico. Playing San Antonio one winter, cast members saw a line of jobless actors outside the theater, waiting for Sadler. He sent each one on with cash and a pat on the shoulder as he turned to hear the next hard-luck story. The impresario’s lackadaisical approach to money tripped him up as the Depression deepened and ticket sales withered. Losses began to show in 1929, but for three years Sadler met his $70,000 annual payroll before he had to cut wages. For a while the box office accepted eggs, produce, and chickens as payment. Despite the downward spiral, in 1931 Sadler bought a new 100×180-foot tent, new scenery, and better seating.

That year’s stand in Austin drew 2,500 ticket buyers, but the bigger top, costly to handle, was too large for small towns. To compensate, Sadler started playing Waco, Galveston, Dallas, San Antonio, and other burgs, staying a month at each. However, city folk were less easily entertained, and downtowns had movie houses, nightclubs, and other attractions absent in the hinterland’s hamlets.

Sadler’s sprawling operation began to bleed red. Fires and windstorms damaged his equipment and his business. And he still was giving away money. By 1935, revenues were nearly invisible and debt a dark, looming mountain. That summer Sadler hired on with a friend’s circus as ringmaster, a desperation move he abandoned after three months. Hoping to capitalize on the Lone Star State’s 1936 centennial, he wrote a play, The Siege of the Alamo, but Texas cities all had their own centennial programs, and Sadler’s script was a clunker.

At the end of 1935, Harley and Billie returned to Sweetwater. They sold their home and show equipment and mortgaged their other real estate, but even so still owed $25,000. In a rented cottage, the couple set about getting out from under.

Harley wrote to 100-odd creditors, asking for time and promising payment in full. Going on the road with a reduced company of players and a small dilapidated tent leased for $1 per day, he worked the Lower Rio Grande Valley. Audiences there still loved the old format, but their enthusiasm did not translate into his former revenues.

Ashamed to bring his tatterdemalion troupe onto stomping grounds where he had strutted proudly, Sadler, through frugal living and strict repayment scheduling, retired his debt. He regained solvency in 1938 and resumed touring West Texas by truck, boasting on his letterhead that he was “completely motorized using Chevrolet Trucks exclusively.” He shrank bookings to a day or two, in 42 weeks playing 112 towns.

In the late 1930s, Sadler bought several oil wells. His wildcatting went spottily, sometimes hitting big and sometimes running dry, never generating steady income. In 1941, he ran for the Texas House of Representatives, winning the seat representing the three counties around Sweetwater. Gloria died in childbirth, along with the daughter she was carrying, devastating Harley and Billie. He stopped touring, sold his show gear, and took refuge in politics, serving on legislative committees overseeing the petroleum industry, teachers’ pay, and prison reform. He was always in the office early and always attentive to constituents. A 1947 attempt at a show business comeback proved his last onstage hurrah. Voters returned him to office twice more. In 1950, he and Billie moved to Abilene, where he ran again for the House and won. Two years later, running unopposed, he was elected that district’s state senator.

Harley Sadler’s health began to decline, in step with finances eroded by a lifetime of generosity. Big Spring Herald reporter Joe Pickle observed that Sadler, though broke, insisted on paying when they met for lunch. In October 1953, emceeing a Boy Scouts benefit in Avoca, Sadler had a heart attack. He died two days later. His memorial service, in Abilene, drew hundreds, including Governor Allan Shivers. But mostly the crowd watching the funeral procession consisted of fans of the Harley Sadler Show, who remembered the fellow in the hearse at the front of the cortege leading a happier parade down some back-country Main Street.