This story, from MHQ’s Summer 2011 issue, won the Army Historical Foundation’s Distinguished Writing Award, announced June 4, 2012.

THE AMBUSH HAD BEEN LAID with practiced precision by a large band of Kiowa warriors led by Satanta, Big Tree, Satank, and Eagle Heart. Hidden in a thicket of scrub oak on Texas’s Salt Creek Prairie, they observed the slow approach of several wagons accompanied by 17 Buffalo Soldiers, the black troopers of the 10th U.S. Cavalry Regiment (Colored). Relatively easy pickings, but no one moved.

Sherman assured Sheridan he

would not allow cruelty

to tie his hands

The previous night, a shaman had prophesied that this small party would be followed by a larger one with more plunder for the taking. The braves were rewarded three hours later when 10 mule-drawn wagons filled with army corn and fodder trundled into view. The Kiowa attacked and quickly overwhelmed this convoy. Seven muleskinners were killed, while five managed to escape. The warriors lost three of their own, but left with 41 mules heavily laden with supplies. It was well after dark before the white survivors reached nearby Fort Richardson and told their harrowing tale to the very officer whose party had passed unharmed under the Kiowa guns: the U.S. Army’s general in chief, William Tecumseh Sherman.

When that raid occurred in May 1871, Sherman was the most prominent of the scores of active army officers who had honed their military skills on Civil War battlefields and were now expected to parlay that expertise into success against the Indians. They brought with them a set of deadly tactics forged in the final two years of the conflict, when gentlemen’s rules had been replaced by no-holds-barred “hard war.”

At war’s end, more than a million officers and men were serving in the Union ranks. With the military tab topping a million dollars a day and a national aversion to large standing armies, Congress hastily whittled this number down, to slightly more than 54,000 by mid-1866. Thanks to low pay and many administrative postings, the core fighting force was less than 25,000 men, and the morale of that inadequately housed army, often working with worn-out equipment, was poor. Still, their officers had far more combat experience than those who led the Indian fighters before the Civil War.

The top national priority became the completion of the transcontinental railroad, a project directly threatened by the Indians of the Southern Plains—the Comanche, Kiowa, Kiowa-Apache, Southern Cheyenne, and Arapaho—led by such smart, fierce chiefs as Satank, Satanta, Big Mouth, and Kicking Bird. Abused by white settlers and resisting efforts to corral them onto reservations, the tribes were raiding homesteads and convoys with impunity, and slowing the railroad’s expansion.

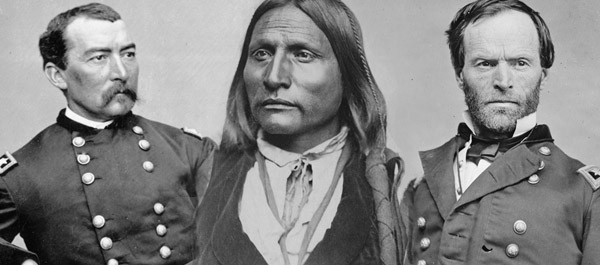

In response, Lieutenant Generals Sherman and Philip Sheridan, two of the Civil War’s most feared Union commanders, developed a strategy that blurred the lines between combatants and noncombatants, bringing hard war to the West.

Had the Southern Plains Indians, ranging virtually unfettered for nearly two centuries, finally met their match?

IN THE ADMINISTRATIVE MUSICAL CHAIRS that accompanied the army’s downsizing, Sherman became the point man for military operations against the free-ranging Indians on the Great Plains. In June 1865 he was put in charge of what became the Military Division of the Missouri, bordering Canada to the north and stretching west from the Mississippi Valley as far as the modern states of New Mexico, Utah, Colorado, and Montana. Sherman began with just three green cavalry regiments led by an officer corps that included 66 former Civil War generals, most of whom had been brevetted to their high station and then reverted to their lower regular army rank at war’s end. In a nod to his adversaries’ skill and tenacity, Sherman later grumbled that to carry out all the tasks required of him, he would need 100,000 men to combat what the general estimated as “a few thousand savages.”

He fervently believed in the destiny and righteousness of the United States. America, he avowed, was intended for a “glorious career in the interest of all mankind,” unless disruptive elements intervened. In the last year of the Civil War, those elements were the Southern leadership class, whose efforts to split the United States represented a mortal sin to Sherman. “We must Kill those three hundred thousand I have told you of so often,” he wrote to his wife to explain why he began to wage hard war.

With the fighting over and the nation at peace, Indians became the focus of his ire. Following the bloody destruction of an 80-man cavalry column in December 1866, Sherman (using the Sioux as stand-ins for all resisting Indians) told then-general in chief Ulysses S. Grant, “We must act with vindictive earnestness against the Sioux, even to their extermination, men, women and children.”

In his orders to Sherman, Grant emphasized that he was to “give the best protection to the overland lines of travel, and frontier and mountain settlements.” For the moment this tied Sherman down to maintaining a series of small forts and outposts along the most heavily used trails, but he could foresee the day when the great technology of the age would alter the landscape. “The completion of the transcontinental railroad,” he declared, would be “as great a victory as any in the war.”

At the beginning of Sherman’s term, the Union Pacific Railroad was 100 miles west of Omaha and extending daily. Its most imminent threat came from the Southern Plains tribes, particularly the Cheyenne and the Kiowa. But Sherman’s planning was hamstrung: The army shared oversight of the natives with the Department of the Interior, whose Indian Bureau operated reservations established to limit tribal movements. Hoping to buy time while a national policy was hammered out in Washington, Sherman turned to another war hero to restore order.

Major General Winfield Scott Hancock had won laurels during the Seven Days’ Campaign, as well as at Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville. Wounded at Gettysburg, he returned for Grant’s Overland Campaign, where his hard-hitting II Corps led the way in some of the war’s fiercest battles. Sherman tapped him to command the Department of the Missouri, effective in the late summer of 1866, authorizing Hancock to notify the Indians “that if they want war they can have it now; but if they decline the offer, then impress on them that they must stop their insolence and threats.”

By the time he arrived at Fort Riley—about 100 miles west of department headquarters at Fort Leavenworth—on March 25, 1867, Hancock had gathered precious little information regarding his foe and knew even less of recent Indian-white history. He marched forth hoping that a simple show of strength would intimidate the tribes he encountered and discourage them from raiding. The expedition would come to epitomize the kind of blind, arrogant soldiering that would so frequently fail against the Indians.

Hancock took into the field a force of 1,400 men, consisting of cavalry, infantry, and artillery. Most of the mounted arm came from the newly organized 7th U.S. Cavalry Regiment, led by its second in command, Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer. Leaving Fort Harker in central Kansas on April 3, 1867, Hancock’s long column marched for two days to Fort Zarah on the Arkansas River, where the general learned that a council of braves awaited him upstream at Fort Larned. When the appointed meeting time came and went with no sign of the chiefs, Hancock was fed a succession of excuses that kept him cooling his heels until April 12. As he was preparing to move out the next day, 15 mounted warriors arrived to talk. It proved a fruitless exercise, and on April 13 Hancock’s force departed Fort Larned on a course toward a Cheyenne village near the Pawnee Fork. There followed more pointless encounters with small Indian parties—until it dawned on Hancock that the Indians were stalling.

On April 14 soldiers encountered a hostile line of some 300 armed warriors. Hancock deployed his troops for action before sending an Indian Bureau agent forward. The agent returned with a dozen mounted warriors, including the Cheyenne chief Roman Nose, who told the general: “We don’t want war; if we did we would not come so close to your big guns.” It soon became evident that these representatives were also stalling, and when his troops finally reached the Pawnee Fork village, all its inhabitants had fled. Unaware of the 1864 Sand Creek massacre in the nearby Colorado Territory—in which a militia force had attacked an encampment of nonbelligerent Arapahos and Cheyennes, killing some 150, nearly two-thirds of them women and children—the general assumed that the villagers had dispersed because they were guilty of something, not that they feared for their lives. After sending Custer to pursue the fugitives, Hancock occupied the abandoned village, uncertain of his next move.

On April 14 soldiers encountered a hostile line of some 300 armed warriors. Hancock deployed his troops for action before sending an Indian Bureau agent forward. The agent returned with a dozen mounted warriors, including the Cheyenne chief Roman Nose, who told the general: “We don’t want war; if we did we would not come so close to your big guns.” It soon became evident that these representatives were also stalling, and when his troops finally reached the Pawnee Fork village, all its inhabitants had fled. Unaware of the 1864 Sand Creek massacre in the nearby Colorado Territory—in which a militia force had attacked an encampment of nonbelligerent Arapahos and Cheyennes, killing some 150, nearly two-thirds of them women and children—the general assumed that the villagers had dispersed because they were guilty of something, not that they feared for their lives. After sending Custer to pursue the fugitives, Hancock occupied the abandoned village, uncertain of his next move.

From Custer came dispatches reporting that several stagecoach relay stations to the north had been burned, with men killed and stock run off. Although he had no evidence, Custer immediately blamed the Pawnee Fork Cheyennes. He then exhausted his supplies and dropped out of the campaign, actions for which Hancock would later bring charges in a court-martial (though Custer claimed he was being made a scapegoat for Hancock’s failed campaign). In retaliation for the raids Custer had reported, and overriding the warning of the Indian Bureau agent that his action would result in an “outbreak of the most serious nature,” Hancock ordered everything in the Pawnee Fork camp destroyed and then marched south to Fort Dodge.

There he found the Kiowa chiefs Kicking Bird and Stumbling Bear, soon joined by several others, including Satanta. During a long conversation on May 1, Satanta’s fervent professions of his peaceful intent so impressed Hancock that he gave the warrior a major general’s coat and a yellow sash. Eight days later Hancock’s expedition terminated at Fort Leavenworth.

THANKS TO HANCOCK’S SACKING of the Cheyenne village, furious Indians ratcheted up their raids on troops and settlers. By the end of the summer, according to one historian, “hostile Indians seemed everywhere, property damage was running into the hundreds of thousands of dollars, and the scalping knife was working overtime.” Telegrams from railroad officials flooded Sherman’s office, demanding protection for their workers. Struggling to counter hit-and-run warrior tactics, the general griped that defending his “old line of 300 miles to Atlanta against [Nathan Bedford] Forrest and the [guerrillas] was easy as compared with this.”

It was not the first time, nor would it be the last, that officers trained in what Sherman termed “high-toned warfare” failed to grasp the complexities of Indian culture, and underrated the natives’ skills at psychological and irregular operations—now commonly referred to as “asymmetric warfare.” Sherman, unhappy with Hancock’s somewhat moderate approach, now sought an officer to lead the Department of the Missouri who was more in line with his thinking. The opportunity to change things up came at the end of 1867 when President Andrew Johnson relieved Philip H. Sheridan of his Louisiana Reconstruction duties and replaced him with Hancock, who was more attuned to the administration’s policies.

Sherman then tapped the fiery and determined Sheridan, whose wartime devastation of Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley had made his name anathema throughout the South, to pacify the Southern Plains tribes.

Sherman had understood since he took the job out West that the pioneers were part of the problem. The “people should not spread out so much,” he said, and he complained that expecting the understrength army to protect settlers was to imagine that “we can catch all the pickpockets and thieves in our cities.” There were other distractions as well, for even as he was directing operations against the Indians, Sherman was fighting administrative battles to determine if civilians or the professional military controlled the army. He looked with great skepticism on the activities of the Indian Bureau, which he disparaged as an “organized system of fraud & rascality.”

He also worried as the Indian policy debate began to emphasize a course of pacification through negotiation. He was certain that force was needed. “I know Indians well enough to believe that they must be made to feel the power of the United States, before they cease their murders & robbery,” Sherman wrote his son in 1871.

The man Sherman now asked to make the Indians feel this power shared his outlook, though without much of the intellectual framework. As Phil Sheridan saw it, the Indians had “only one profession, that of arms, and…they never can resist the natural desire to join in a fight if it happens to be in their vicinity.” The only answer to their resistance was to force them onto reservations and eliminate those who would not comply.

Sheridan respected the Indian warriors as a soldier respected his foe. Once they chose the way of war, he believed, they necessarily involved all members of their communities. If “a village is attacked and women and children killed,” he argued, “the responsibility is not with the soldiers but with the people whose crimes necessitated the attack. During the [Civil War] did any one…cease to throw shells into Vicksburg or Atlanta because women and children were there?”

He actively encouraged destruction of the great southern buffalo herd, recognizing its critical importance to the nomadic Plains communities. And he understood some aspects of this fight were unlike the Civil War, where certain rules applied when battle was joined. Captured U.S. soldiers could expect little mercy, and Indians who resisted could expect no quarter from Phil Sheridan. During an 1869 tour of his outposts, he was introduced to a Comanche leader self-described as a “good Injun.” Sheridan smiled and said, “The only good Indians I ever saw were dead.” (It was a phrase that would echo through American culture as “The only good Indian is a dead Indian.”)

Sheridan took charge of the Department of the Missouri in March 1868 and quickly put his Civil War experience to use. To gather intelligence on the native camps, he hired several white scouts—with ties to both Indians and whites—who regularly briefed him on Indian plans and movements. Recalling how Rebel irregulars in the Shenandoah Valley were countered by mobile bands of Union rangers, Sheridan turned to his capable and ambitious assistant inspector general, Major George A. Forsyth, to “employ fifty first-class hardy frontiersmen to be used as scouts against the hostile Indians.” The immediate result was one of the most dramatic encounters in all the Indian Wars.

CHEYENNE, KIOWA, AND COMANCHE bands had rung in 1868 with a succession of bloody raids into northern Texas, northwestern Kansas, and eastern Colorado, killing or kidnapping isolated settlers and rustling their stock. Sheridan, who was planning a major operation for late in the year, tried to keep a lid on things with small-unit strikes. Major Forsyth, his second in command Lieutenant Frederick H. Beecher, and 48 scouts left Fort Hays in central Kansas in late August, well mounted and armed with Spencer repeating rifles and Colt revolvers. Chasing rumors and trailing raiders, Forsyth’s band reached the Arikaree Fork of the Republican River just across the Colorado line where, early on September 17, they were surprised by a large force of Cheyennes, Sioux, and Arapahos.

The scouts scrambled to find the best defensive ground—in this case, an island in the Arikaree some 40 feet wide and 200 feet long. The moat was just a few inches deep, but it provided a clear field of fire for the riflemen, who frantically burrowed behind slight cover even as they abandoned most of their rations and all of their medical supplies in their hasty retreat. Several mass rushes by the Indians were beaten back with the help of the seven-shot Spencers, though at a steep cost. By the end of the day Lieutenant Beecher was dead, along with three others; Forsyth had been shot through both legs and all the horses had been killed. During the first night, two of the scouts slipped away for help, which was 85 miles distant. The Indians attempted no more large assaults, but the sniping was constant.

When a relief force arrived a week later, Forsyth counted 6 dead and 15 wounded. He reported he had faced some 750 hostiles and killed 32, though modern estimates have lowered the Indian dead to nine, among them the Cheyenne leader Roman Nose. This affair, now referred to as the Battle of Beecher Island, ended Sheridan’s experiment with independent mobile ranger detachments (other than as complements to conventional forces), but confirmed for him the absolute necessity of mounting a major offensive against the Southern Plains Indians.

Sherman and Sheridan decided to fight a winter war, when warriors were most vulnerable and had to remain close to their villages. As Sherman put it, “an Indian with a fat pony is very different from him with a starved one.” Sheridan put together a plan for a sustained, six-month operation. “I made up my mind,” he later wrote, “to confine operations during the grazing and hunting season to protecting the people of the new settlements and on the overland routes, and then, when winter came, to fall upon the savages relentlessly, for in that season their ponies would be thin, and weak from lack of food, and in the cold and snow, without strong ponies to transport their villages and plunder, their movements would be so much impeded that the troops could overtake them.”

Taking full advantage of the railroads to move troops and provisions, Sheridan ensured that large caches of supplies were secreted at strategic points. He and his officers carefully examined maps and questioned grizzled trappers about local weather conditions. A rigorous training regimen hardened the men for the campaign. Sherman also crafted wide-open rules of engagement, assuring Sheridan that he would “say nothing and do nothing to restrain our troops from doing what they deem proper on the spot, and will allow no mere vague general charge of cruelty or inhumanity to tie their hands.”

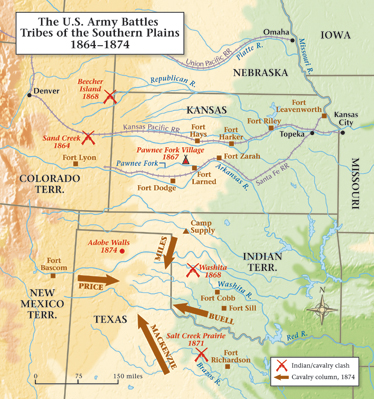

Intelligence put the resisting tribes near the North Fork of the Red River. It was here that the army tried out the tactic that would be used time and again to help win the Indian Wars, one entailing the convergence of two or more heavily armed columns on one or more tribes.

Three independent columns would converge near the North Fork, forcing the Indians to fight, surrender, or flee into Texas. One would be staged from Fort Bascom in eastern New Mexico, where Colonel George W. Getty commanded. In 1864, Getty had campaigned under Sheridan in the Shenandoah Valley. Departing from Fort Lyon in southeastern Colorado and angling into the region from the northwest was a second column under Major Eugene A. Carr, who received the Medal of Honor for gallantry at the 1862 Battle of Pea Ridge. The third column, which Sheridan anticipated bearing the brunt of the fighting, would drive south from Fort Dodge and was to be led by Lieutenant Colonel Alfred Sully, who had previously served in the east under Major Generals George McClellan, Ambrose Burnside, and Joseph Hooker. Once a highly regarded Indian fighter, Sully had in Sheridan’s opinion lost his edge, so he sprang Custer from Hancock’s court-martial and handed him command of the 7th. Sheridan would accompany this column.

Sheridan left his field headquarters at Fort Hays early on November 15, 1868, and after pressing south for two days through a cold and windy rainstorm, connected with his escort force at Fort Dodge. On November 21, Sheridan and his party reached an advance food and munitions dump dubbed (as all were) Camp Supply. There he found Sully and Custer feuding over seniority, a problem he resolved by sending the former packing to district headquarters.

A snowstorm whirled in on the evening of November 22 and continued through the next day. Undaunted, Custer had the 7th saddled and ready to go, though visibility was near zero at times. Sheridan had his doubts, but Custer was adamant that his men could move while the Indians could not. Sheridan’s orders were blunt and direct: Custer was to proceed to whatever Indian encampments he encountered and, since tribes not on reservations were presumed hostile, “destroy their villages and ponies, kill or hang all warriors, and bring back all women and children.” According to newspaperman B. Randolph Keim, Custer’s “command moved out with cheers and the highest anticipations of inaugurating the campaign by striking a decisive blow.” With his usual theatricality, Custer had the regimental band play “The Girl I Left Behind Me” as the column, some 700 riders, dissolved into the snowy haze.

Sheridan had arranged to augment his regular army strike force with a militia cavalry regiment from Kansas, but it failed to appear on time, so Custer departed without the extra guns. It wasn’t until November 28 that the leading elements of the Kansas reinforcements arrived, exhausted and hungry, requiring another week before they could be employed in active operations.

ON THE MORNING OF NOVEMBER 27 a colorful white scout known as “California Joe” entered camp bearing Custer dispatches. The 7th had located a Cheyenne village on the Washita River after four days of hard marching through the snow. Custer had promptly attacked, and following several hours of fighting reported killing 103 hostiles while capturing 53 women and children. (The numbers remain in dispute.) Among the slain was Chief Black Kettle, who, ironically, favored accommodation with the whites. Only after the engagement was under way did Custer learn of other nearby villages, forcing him to withdraw before the more numerous hostiles could organize a counterattack. Sheridan saw this all as good news. He sent a congratulatory message to Custer and a note to Sherman promising that “if we can get one or two more good blows there will be no more Indian troubles in my Department.”

Custer’s victorious legion returned to Camp Supply on December 2 and, never one to miss an opportunity, the 7th’s commander had his men pass in review before their pleased general. Directly behind the command party came the spoils of victory, the Cheyenne women and children captured in the attack. “They were,” remembered the reporter Keim, “mounted on their own ponies, seating themselves astride the animals, their persons wrapped in skins and blankets, even their heads and faces being covered, leaving nothing visible but the eyes.” Only later did Sheridan realize that his protégé had failed to ascertain the fate of a small party of troopers led by the 7th’s second in command, Major Joel Elliott, which had become separated from the main body during the melee. He deemed this “the only drawback to the very successful operation.”

In Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, Sheridan had learned the value of vigorously pressing a defeated enemy. Once the battered 7th was sufficiently rested and reequipped, he intended to go after the other rebellious Indian villages. On December 6, after an overnight snowfall of eight inches, the now 1,700-man column marched toward the Washita, with Sheridan along to observe and Custer in command. Even before he departed from Camp Supply, Sheridan’s brutish strategy was paying dividends. Surprised and shocked by the winter offensive, the affected tribes gathered in one grand encampment. There were several Kiowa bands under Satanta, Satank, Woman’s Heart, and Big Bow as well as some Comanche factions and large groups of Cheyennes and Arapahos. But the house was divided. Some wanted to fight, others to submit by seeking sanctuary at Fort Cobb in central Indian Territory. Even as Sheridan’s fighting column was on the move, the Indians too were in motion, with only the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and a few Kiowa bands continuing the struggle.

If Sheridan was hoping to test his concept of winter operations, Mother Nature obliged. Just a day out from Camp Supply, sleet, snow, and bone-chilling winds pummeled his men and animals; at times they could barely eke out one mile an hour. But Sheridan never flinched. Finally, on December 10, they made camp near the site of Custer’s Washita fight. Letting his men rest in their tents for a day, Sheridan insisted on a guided tour of the battlefield. Before long he cut the trail of the unfortunate Major Elliott’s party, discovering the human detritus that marked their last stand.

“The poor fellows were all lying within a circle not more than 15 or 20 paces in diameter,” Sheridan recalled, “and the little piles of empty cartridge shells near each body showed plainly that every man had made a brave fight. None were scalped, but most of them were otherwise horribly mutilated.” Sheridan was both repelled and fascinated by the Indian treatment of enemy captured and slain. He could never acknowledge any cultural imperatives for such barbarity, seeing it as further confirmation that the Indians were a “wild and savage people.”

The march resumed on December 12, bringing the column through hastily abandoned Arapaho and Kiowa villages. The bodies of a white woman and her child were found, captives whom Sheridan had hoped to liberate. For the next five days the soldiers labored mightily to carve a passage across icy ravines, frozen streams, and through heavy snowdrifts. Sheridan eventually made it to Fort Cobb, where he began the arduous negotiations for the resettlement of hundreds of Plains Indians who—fleeing before his three converging columns—had finally wearied of war.

“Of course,” he afterward remarked, “the usual delays of Indian diplomacy ensued,” and it wasn’t until February that the last of the nonmilitant resisters were moved onto reservations. Once these defeated Indians had been transferred, Sheridan turned to the task of hunting down the remaining rebellious warriors.

FOR THIS FINAL PUSH, he and Sherman had to reckon with growing negative public opinion in the East and evolving government policy. For the most part, the Union generals during the Civil War had enjoyed popular support. Congress had largely kept its hands off army policy. But in Indian matters, the American people—especially in the more populous East where newspapers often highlighted broken government promises and mistreatment of reservation tribes—were divided over whether the enemy were culprits or victims. Much to Sherman’s surprise, his good friend U.S. Grant, who became president in March 1869, wanted to resolve the issues with minimal bloodshed. That emboldened members of Congress still uncomfortable with the size of the army. By an act passed in early 1869, it was pared down even more. Not coincidentally, Kiowa and Comanche raids into Texas below the Red River increased dramatically that year and the next. Prominent among the raiders were Kicking Bird and Satanta, who was occasionally sighted clad in the uniform Hancock had given him.

Grant’s election as president in 1868 cleared the army’s two top slots, which were quickly filled by the nation’s premier Indian fighters: Sherman became the army’s sole full general, and Sheridan its only lieutenant general. Each fiercely opposed the public clamor for a kinder and gentler Indian policy. Sherman allowed that while they did live in a “free country,” the facts had been misrepresented and the public “humbugged” into believing that Chief Black Kettle’s Cheyennes were innocent when Custer ravaged their camp.

SHERMAN’S APPOINTMENT meant he had to move to Washington while Sheridan, given his pick of assignments, chose to head the Department of the Missouri. National policy continued to divide responsibility for oversight of the Indians; the Indian Bureau kept control as long as the natives remained on the reservations, while the army policed and pursued rebels outside the boundaries. With the power of the great tribes of the Southern Plains seriously diminished by Sheridan’s winter campaign of 1868–1869, the conflict devolved to hit-and-run raids, often with the native warriors operating from the relative sanctuary of the reservations. Several “graduates” of the Civil War became just as well known for their effective pursuit of the raiders. Among them were Colonel Benjamin H. Grierson, Brigadier General George Crook, and Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie.

This phase of the Indian’s offensive on the Southern Plains wiped out many isolated family homesteads, but caused little property damage and few casualties. However, the outcry from western officials, politicians, citizens, and newspapers was shrill, and Sherman was not deaf to their entreaties. Even though he believed that many of their claims were wildly exaggerated, he was always eager to engage in some “wild roving about,” and to personally take his war to the Indians. It was one such tour of his western outposts in 1871 that led him across the Salt Creek Prairie to the close call with the Kiowas who destroyed the mule train that followed his party.

Several days after the incident the general in chief met some warrior notables—Satanta, Satank, Kicking Bird, and Big Tree among them—who had come to draw rations at Fort Sill. After Satanta boasted of a recent Texas raid, Sherman ordered several of the chiefs arrested and sent to the Lone Star State for trial. An escort provided by Colonel Mackenzie took the prisoners south, but less than a day out Satank staged a suicidal escape attempt and was gunned down and killed. Satanta would be found guilty, sentenced to hang, then pardoned after a public outcry in the East. Upon his return he resumed raiding, was later imprisoned again, and eventually killed himself.

Conflict roiled the Southern Plains for the next three years, culminating in the spring of 1874 in what became known as the Red River War. Blame all the usual reasons: the government’s failure to deliver promised rations to the reservations, unpunished white raids on their property, frustration over dwindling buffalo herds, and a cultural preference for martial action. The vengeful Indian raiding groups grew in size until several hundred Comanches and Cheyennes attacked a base camp for buffalo hunters at a place called Adobe Walls, in the Texas Panhandle. The attack was beaten off with few casualties, but Sheridan saw an opportunity to finish the work he had begun in 1868. He planned to repeat his winning convergence tactic with more forces, this time not bothering to wait for winter, and he obtained permission to enter the hitherto off-limits reservations while in hot pursuit. Now, Sheridan promised Sherman, he would “settle the Indian matter in the Southwest forever.” His intelligence sources pinpointed the remaining Indian concentrations in northern Texas, west of the Indian Territory.

Pushing south out of southwestern Kansas was a force led by Colonel Nelson Miles, while from west-central Texas the reliable Colonel Mackenzie would thrust north. Pressing in from the west was a column under Major William R. Price, while another under Lieutenant Colonel George P. Buell marched in from the east. With temperatures rising to record levels in the summer of 1874, the Indians found their mobility limited by dried up water holes and sun-baked grass.

Still, because the warriors avoided significant confrontations, months of steady and costly operations failed to produce a headline victory, though more and more Indians surrendered. Ultimately it was troops under Miles and Mackenzie who wrecked the last major Indian encampments (especially horses and supplies) as winter was approaching. Watching the ragged survivors stumble onto reservations, one Indian Bureau agent observed that “for the first time the Cheyennes seemed to realize the power of the Government, and their own inability to cope successfully therewith.”

With that, Sherman’s eight-year war in the Southern Plains drew to a close. There would still be localized outbreaks of resistance to U.S. authority, but the once active nomadic communities were a thing of the past. The army’s main theater of action shifted to the Northern Plains, where tribes led by the powerful Sioux under such famed chiefs as Sitting Bull, Gall, and Crazy Horse would confront the full force of the U.S. Army. Once again, operating in an arena where space allowed for extended maneuver, the army would rely on sustained harassment to destroy native sustenance and send converging columns forth against warrior concentrations to break the back of resistance.

Restoring order to the Southern Plains permitted the railroads to branch outward from the main east–west line (completed in 1869), greatly aiding settlers. For Sherman it was progress triumphant as the Indians who had contested the great flood of civilization had been “substantially eliminated from the problem of the Army.” Sheridan too was pleased, proud that his strategy succeeded and that the officers and men of the U.S. Army overcame everything nature and natives could muster. “This campaign was not only very comprehensive,” he declared in 1875, “but was the most successful of any Indian campaign in this country since its settlement by the whites.”

Contributing editor Noah Andre Trudeau is the author of Bloody Roads South, The Last Citadel, Out of the Storm, and Like Men of War. He is currently researching Abraham Lincoln’s time at the front near Petersburg in the spring of 1865. In addition to winning the Army Historical Foundation’s 2011 Distinguished Writing Award for this piece, he has received the distinguised Fletcher Pratt Award and the Jerry Coffey Memorial Book Prize. Formerly an executive producer at National Public Radio, he lives in Washington, D.C.