If there is one repetition you can count on in the United States other than paying taxes, it is that another recession will follow the one we’ve just endured. The only question is how long we’ll skate by until the next one arrives. There have been 47 recessions in the U.S. since 1790, statistically one every 4.6 years. The good news in this unnerving cycle is that the duration of recessions is diminishing. A typical recession in America’s first hundred years lasted an average of two years. Since 1945, recessions have averaged 10 months. Most people seem shocked when another recession comes along, but economists long ago accepted them as inevitable. “We have cycles,” says Eugene White, a professor of economics at Rutgers University. “Sometimes we get a little too wild. We over expand and we have a recession.” Nonetheless, there are recessions, and there are recessions. Although the downturn of 2008-09 is often said to be the worst since the Great Depression, the perspective of history shows that the nation has experienced far worse times far more often than one might guess. On the pages that follow are accounts of nine historic busts that tested the optimism and resilience of Americans who lived through them.

Great Land Bust of 1819

A prolonged economic boom following the War of 1812 culminated in America’s first major recession. Easy lending practices by banks fueled land speculation as settlers poured into the West. But the bubble burst in 1819 when the Second Bank of the United States nearly went bankrupt and began calling in all its loans. In the panic that ensued, land values fell by half, and tens of thousands of settlers lost property to foreclosure. Bankruptcy sales took place almost daily in Cincinnati, then the largest city in the Northwest. In some parts of the frontier, whiskey and grain replaced cash. Shops, apothecaries and taverns in Northern cities went out of business. For the first time in the history of the young republic, large numbers of people in cities were out of work: 50,000 in New York, Philadelphia and Baltimore. Meanwhile, thousands of people were sent to debtors’ prisons. In his autobiography, newspaper mogul Horace Greeley recalled a surprise sunrise visit to his family’s small New Hampshire farm by local authorities in August 1820. “The sheriff and sundry other officials, with two or three of our principal creditors, appeared, and— first formally demanding payment of their claims—proceeded to levy on farm, stock, implements, household stuff, and nearly all our worldly possessions but the clothes we stood in,” wrote Greeley, whose father hid to avoid imprisonment. At age 10, Horace went to work as a day laborer to help support the family following the loss of their farm.

Cotton Crash of 1837

Recommended for you

The rush to build canals and railroads in the 1830s also led to widespread land speculation. One Chicago lot worth $33 in 1829 was offered for $100,000 in 1836, following the news that a canal would be built linking the small village to the Mississippi River. President Andrew Jackson attempted to end the speculation by issuing an executive order requiring public land to be paid for in silver or gold rather than cash. Meanwhile, officials at the Bank of England raised interest rates out of fear that British investors were overexposed to America’s economic bubble. The move dampened British demand for cotton, America’s chief export, driving down prices. The cotton market in New Orleans collapsed in March 1837 and brought New York creditors down with it. Banks besieged by panicked speculators stopped converting paper money into gold or silver. Forty percent of the 850 banks in the United States soon closed. Ninety percent of the factories in Eastern cities shut down, and unemployed workers seeking refuge in poorhouses were turned away for lack of space. One of the unemployed was young Herman Melville, whose family’s fur and cap business in Albany, N.Y., failed. A long, futile search for work eventually prompted Melville, then 21, to sign up to work on a whaling ship, which inspired his novel Moby Dick.

Railroad Meltdown of 1857

Panic derailed the nation’s railroads and banks on the eve of the Civil War. An extended period of prosperity in the wake of the California Gold Rush ended abruptly when the Ohio Life and Insurance Trust Company, which had invested $3 million of its total assets of $4.8 million in railroads, declared bankruptcy in August 1857. Financiers panicked, firms suddenly found it impossible to get credit, and bank depositors started withdrawing gold. The sense of panic grew in early September when a steamer carrying California gold and 400 passengers to New York was lost at sea in a hurricane. Hundreds of banks and half of New York City’s brokerage houses, which were heavily involved in railroads, failed. Continued bank runs finally forced New York banks to suspend operations in October, and banks across the country followed suit. Thousands of businesses failed, including threefourths of all railroads. Illinois Central was saved from bankruptcy by its able attorney, Abraham Lincoln, who won two state Supreme Court cases over back taxes that would have pushed the company into insolvency. Lincoln continued to represent Illinois Central up until his nomination for president in 1860 and later named its chief engineer, George McClellan, commander of the U.S. Army. He also eventually made his final trip home from Washington, D.C., to Springfield on a flag-draped Illinois Central funeral train.

Bank Collapse of 1873

A flurry of railroad construction following the Civil War came to a grinding halt in September 1873 when Jay Cooke and Company, which had accumulated huge debts to finance the Northern Pacific Railroad, went bankrupt. The news caused panic selling on Wall Street, prompting the New York Stock Exchange to close for 10 days for the first time in its history. A wave of bank failures followed. Unemployment approached an estimated 14 percent, and the word “tramps” was coined to describe the hordes of men wandering the country looking for work. In Pittsburgh, Andrew Carnegie was forced to temporarily halt construction on a huge steel plant because his customers couldn’t pay their bills. But the enterprising 37-year-old sold other holdings in order to complete his state-of-the-art factory. Once it opened, he kept the production line going nonstop and took all orders no matter how low the price. He recouped his entire investment within two years. The age of steel began, and Carnegie went on to become the richest man in the world.

Gold Run of 1893

The failure of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad in February 1893, combined with a run on gold by foreign and domestic investors, helped lead to a stock market and banking collapse. Uneasiness turned to panic after the National Cordage Company, which had attempted to corner the market on imported hemp, declared bankruptcy. Unprecedented bank runs soon followed. Unemployment peaked at an estimated 17 percent a year later and remained above 10 percent for half a decade. The recession triggered violent strikes, including one by railway workers against the Pullman Palace Car Company that shut down much of the nation’s transportation system in July 1894. Farmers were hardest hit by the chaos. Rose Wilder Lane, daughter of writer Laura Ingalls Wilder, was 7 years old when her family left South Dakota in 1894 after losing their farm. “The whole Middle West was shaken loose and moving,” Lane wrote in the 1930s. “We joined wagon trains moving south; we met hundreds of wagons going north; the roads east and west were crawling lines of families traveling under canvas, looking for work, for another foothold somewhere….The country was ruined, the whole world was ruined; nothing like this had ever happened before. There was no hope, but everyone felt the courage of despair.”

Bank Rescue of 1907

A nationwide financial panic erupted in October 1907 when the Knickerbocker Trust Company in New York went bust. Rumors that its president was linked to a scheme to corner the copper market had prompted a run by depositors. J.P. Morgan, the nation’s most powerful financier, averted a collapse of the banking system when he organized an ad hoc consortium that anted up $35 million to help rescue several of the nation’s largest trust companies, the New York Stock Exchange, the city of New York and a major brokerage house. The federal government added $35 million to the pot. At the time the U.S. did not have a central bank to control the national money supply. The panic of 1907 led to the creation of the Federal Reserve six years later.

Price Tailspin of 1920

The shift to peacetime production after World War I, as well as the Federal Reserve Board’s decision to raise interest rates to record high levels in an effort to curb postwar inflation, resulted in the most precipitous price decline in U.S. history and a severe recession. The biggest drop was in farm prices. Meanwhile, overall business activity decreased by nearly one third and an estimated 4 million people lost their jobs. The Kansas City haberdashery that Harry Truman owned with his army buddy Edward Jacobson was among the businesses that went bankrupt. Another door opened for 37-yearold Truman when the local Democratic boss asked him to run for county judge. Truman won the election. It took him 15 years to pay off his business debt, and the experience made him a fiscal conservative. Indeed, the U.S. would run budget surpluses in four of Truman’s eight years as president.

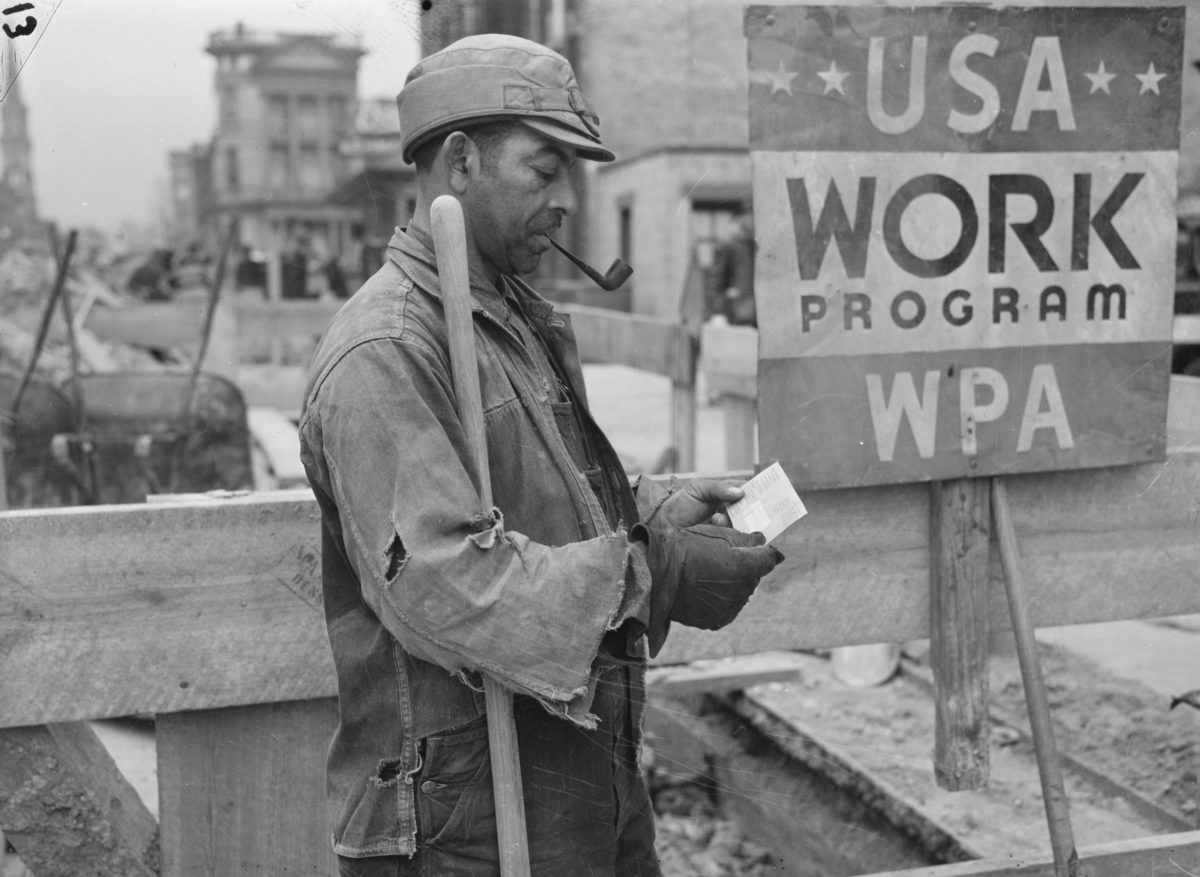

Stock Market Crash of 1929

When the value of stocks plummeted in 1929, public officials and the press insisted that nothing was wrong and that people should have more faith in the economy. The stock market regained more than half its losses by April 1930, but a general economic downturn subsequently forced hundreds of thousands of farmers into bankruptcy, causing a series of bank failures in the South and Midwest that fall. People rushed to banks to convert their deposits into hard currency. By the time President Franklin D. Roosevelt took office in March 1933, some 4,000 banks had shut down, onethird of the nation’s farms had changed hands, and more than 12 million people —23.6 percent of the population—were unemployed. The psychic damage was immeasurable. In his memoir, Growing Up, Russell Baker, recalled a visit to a relief depot in Baltimore to pick up surplus food. His mother covered the food with her coat to hide the telltale packaging. “Being on relief was a shameful thing,” Baker wrote. “People who accepted the government’s handouts were scorned by everyone I knew as idle no-accounts without enough self-respect to pay their own way in the world. I’d often heard my mother say the same thing of families in the neighborhood suspected of being on relief. These, I’d been taught to believe, were people beyond hope.”

Fed Rate Hikes of 1980

A sharp increase in the price of oil in the wake of the 1979 Iranian Revolution capped a decade of stagflation —simultaneous economic stagnation and inflation—and resulted in a national energy crisis. A $1 billion government bailout of Chrysler Corporation in January 1980 became emblematic of the economic malaise. Meanwhile, in an effort to combat double digit inflation, Federal Reserve Board Chairman Paul Volcker pushed interest rates higher until the prime hit a record 21.5 percent in December 1980, sending car sales and homebuilding into a tailspin. In the summer of 1982, business bankruptcies and bank failures reached Depression-era levels. Auto dealers sent Volcker car keys urging him to “unlock the economy.” Farmers circled the Federal Reserve headquarters on their tractors. Unemployment peaked at 10.8 percent in late 1982. Costly unionized manufacturing workers found themselves displaced as hundreds of Northern factories closed and later relocated to non-union states in the South or overseas. And former union members faced a new reality. “We put three guys in a little machine shop making $9.18 an hour to start, which isn’t bad, and in three days they were talking union,” Nancy Nagle, head of a federal job program in Michigan, told the New York Times. “So, naturally, they were right back out on the street. We get people used to making the big bucks, working fairly close to home, with a union and good benefits, but things have changed now. It’s an employer’s market, and that discourages a lot of guys.”

Susan Mandel is a freelance journalist who has written for the Washington Post Magazine, the National Law Journal and People.