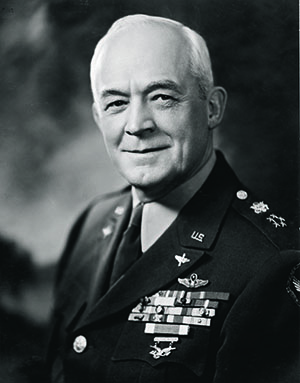

In November 1938 Charles Lindbergh wrote urgently to Major General Henry Harley “Hap” Arnold, the new chief of the Army Air Corps. Touring Germany, the aviation hero had witnessed the surging Luftwaffe firsthand.

“Germany is undoubtedly the most powerful nation in the world in military aviation and her margin of leadership is increasing with each month that passes,” Lindbergh wrote. “In a number of fields the Germans are already ahead of us and they are rapidly cutting down whatever lead we now hold in many others.”

Arnold, on the job little more than a month, took Lindy’s warning to heart. He summoned to the National Academy of Sciences a group of researchers and university administrators, including MIT president Vannevar Bush and California Institute of Technology physicists Robert Millikan and Theodore von Kármán. Some military men thought Arnold was wasting time talking to “longhairs.” Invited by his old friend to lunch with the scientists, General George C. Marshall balked. “What on earth are you doing with people like that?” Marshall asked.

“Using their brains to help us develop gadgets and devices for our airplanes that are far too difficult for the air force engineers to develop themselves,” Arnold replied.

Doctrinaire officers might not have thought to look on campus for help winning wars, but for Arnold the leap was logical. As one of the world’s first licensed pilots, trained at the Wright brothers’ own flying school and mindful that might requires science, technology, and solid design and planning, Arnold conceived a vision of America as an air power and, simultaneously balancing immediate needs with the necessity of peering into the future, nurtured a tiny, feeble armed service into an aerial armada capable of winning a world war.

Hap Arnold’s career began with disappointment. A surgeon’s son who fulfilled his father’s dream by graduating from West Point in 1907, Arnold loved the cavalry, drawn by its prestige and his love of riding. At graduation he proudly ordered a new uniform with trouser stripes of “glorious Cavalry Yellow.”

When Arnold received his commission, however, he found that middling grades and a history of pranks had relegated him to the unglamorous peacetime infantry. Devastated but determined, he volunteered to go to the Philippines on a map-making expedition, the most exotic option available. Arnold so impressed his supervisor that in 1911 the captain rescued the young Pennsylvanian, now twiddling his thumbs at Governors Island in New York Harbor, from barracks-bound boredom.

Congress had just spent $25,000 to buy three Wright biplanes and two made by Glenn Curtiss, and soldiers were going to learn to fly them at the Wright brothers’ facility in Dayton, Ohio. Arnold’s former captain, assigned to pick two of America’s first military airmen, thought Arnold had the right stuff.

At Dayton, Arnold absorbed lectures by the Wrights, completed 28 lessons, and logged 228 minutes of flying time before his training was judged done. Transferring to College Park, Maryland, near Washington, D.C., he set up a Signal Corps flight school with the army’s only other aviator. The two wrote manuals, standardized methods, and taught soldiers to fly. In 1912 Arnold won the first Mackay Trophy for military flight when, in a prescient display of aerial technique, he observed and reported troop movements near the capital.

A near-crash over Kansas put Arnold off planes; he knew too many Army aviators who had augered in. He returned to Washington as aide to the chief of the Signal Corps, meeting many future military aviation stars, such as Captain William D. “Billy” Mitchell, at that point not yet flight-qualified. In September 1913 Arnold married Eleanor “Bee” Pool. The next year, another Philippines posting landed the Arnolds at Fort McKinley, Luzon, where Arnold forged strong bonds with his next-door neighbor, Lieutenant George Marshall. After a stint in upstate New York Arnold was ordered to Rockwell Field, nearly San Diego, California. Pressed by Mitchell, and drawn by an immediate promotion to captain plus a newly instituted pay increase of 50 percent for hazardous duty, Arnold resumed flying.

The ambition and stubbornness that enabled Arnold to return to the cockpit could rankle superiors. At Rockwell Field, California, his commander correctly asserted that Arnold had disobeyed orders when he and others searched for two lost airmen. In fact the commander had dithered, so Arnold had done what he thought best in a crisis. Army authorities reprimanded Arnold’s boss; the next efficiency report he wrote about Arnold might have sunk other men but Arnold’s otherwise stellar record overrode it.

As the United States entered the Great War, Arnold yearned for action but spent the duration managing aircraft production for the newly fledged Army Air Service. The war was nearly over before Arnold reached Europe with a party demonstrating the Kettering Bug, an unmanned papier-mâché and cardboard “aerial torpedo” that weapons inventor Charles Kettering had cooked up with a team of scientists that included physicist Robert Millikan, whom Arnold got to know on the trip. Americans were bad at building fighting planes, Arnold thought. “The failure of aircraft production in 1917–18 remained uppermost in my mind,” he later wrote.

After the war, control of the Army Air Service fell to ground-pounders who saw fliers as handmaidens to the infantry and artillery. As Air Service ranks shrank from 190,000 to 27,000, Arnold found common cause with likeminded aviators Lieutenant Colonels Billy Mitchell and James Doolittle, Major Carl Spaatz, and Lieutenant Ira Eaker—all of them arguing for what they saw as America’s military future.

Personal and professional setbacks—his toddler son’s death, a plane crash, a bout with ulcers—rocked Arnold, but he pressed on. Another Washington posting inserted him into the debate over which weapon would predominate: aircraft or dreadnought. His pal Mitchell so fiercely criticized army reluctance to embrace aviation that he was court-martialed, and so almost was Arnold—for touting air power to Congress and the media. Given 24 hours to decide if he wanted to resign or face a tribunal, Arnold stood firm. His critics backed down, but as penalty for his audacity exiled him to Fort Riley, Kansas, to teach flying. It was a toss into the brambles, but one that had him training the men who would fly the nation’s warplanes and enabled him to advance aviation as a combat arm.

In Kansas, Arnold, now a major, hit the 20-year mark. He thought of retiring; he had been offered the presidency of Pan American Airways. But he chose to stay in uniform. Success at Fort Riley led to the Command and General Staff College, a prestige appointment whose infantry-besotted curriculum irked Arnold. “Well, we fought the battle of Gettysburg again today, and guess who won?” an exasperated Arnold asked Bee one evening. “Meade did it again, but think what Lee could have done with just one Wright airplane.”

On graduation day, he had Bee wait with the children in the car with the motor running by the field house so he could see Fort Leavenworth disappear in the rearview mirror as fast as possible.

In November 1931, Lieutenant Colonel Arnold took command of the air base at March Field, California. He looked up Bob Millikan, who in 1923 had won the Nobel Prize in physics and now ran nearby California Institute of Technology. The bond begun with the Kettering Bug paid off. Millikan got planes for research; Arnold got access to Caltech’s scientific resources, including wind tunnels and aerodynamics lab, managed by Theodore von Kármán, a brilliant Hungarian.

This came at a time when the Air Corps, as it was now called, was looking to buff its image with flying shows and record-setting flights. Arnold garnered coverage for the service in another way when an earthquake slammed Long Beach in 1933. He organized and dispatched emergency supply convoys with an alacrity that first nettled 9th Corps Commander General Malin Craig because Arnold had run roughshod over command protocol. However, once Craig understood the gravity of the situation, he voiced admiration for his energetic subordinate. In 1934, Arnold again made aerial news when he led 10 Martin B-10s, the country’s first all-metal monoplane bombers, from Washington, D.C., to Alaska and back.

In Fairbanks, Arnold had an odd visitor. A man claiming to be a defecting German spy warned him that the Nazis had planes better than the B-10. Arnold dismissed the fellow as “a damned liar,” but reported the encounter to War Department intelligence officers and recommended an inquiry into what turned out to foreshadow Charles Lindbergh’s warnings.

Later that year, Congress summoned Arnold to testify on the Air Corps. Asked if, given the chance, he could “straighten out” the corps, Arnold said he was sure he could. He had hoped the Alaska flight would bump him to brigadier, but that had to wait until Craig became army chief of staff and General Oscar Westover, a year ahead of Arnold at West Point, took over the Air Corps.

In January 1936, Arnold got his promotion and was named Westover’s assistant. Boeing was developing a four-engine successor to the B-10 intended to realize Billy Mitchell’s vision of a global bomber fleet. The Corps saw its future in the B-17 Flying Fortress, which Arnold later called “a turning point in the course of air power.” But even before the first Fortress went into operational testing in March 1937, political opposition and interservice rivalry threatened to ground it. Critics said the B-17 was too new, too big, too experimental, too untested. Why buy heavy long-range bombers? Arnold and Westover fought back, in their 1938 budget requesting 50 more B-17s. Congress cut them. Production picked up in 1941 but not until after the U.S. entered the war did the floodgates open.

On September 21, 1938, Westover was over Burbank, California, testing a plane when its engine stalled. The crash killed him and his crew chief. Arnold assumed Westover’s duties in an acting capacity. A week later, as British and French officials huddled in Munich, Germany, preparing to give Hitler the Sudetenland, President Roosevelt called in his cabinet and military leaders, including the acting air chief.

Only airpower would faze Hitler, Roosevelt declared. He said he wanted planes—now—and many more than the 178 stipulated in the 1940 budget. Of the nation’s 5,000 military aircraft, only half were built for combat. Shocking nearly all present save Arnold, FDR demanded a production goal of 10,000 planes a year, with capacity for 20,000 going all-out. Roosevelt said he felt alarm not only about American airpower, but Allied readiness. He asked Arnold for numbers.

Arnold gave the news straight. England, he estimated, had 1,500 to 2,200 combat-ready craft; France, perhaps 600. Germany had at least 6,000 combat-ready frontline warplanes, with 2,000 more in reserve. But airpower meant more than fleet size, Arnold cautioned: exacting standards for production and pilot training were paramount, as was base construction.

That convinced Roosevelt, who said he wanted immediate action, and more heavy bombers. Arnold left the White House feeling that the Air Corps had “finally achieved its Magna Carta.” The next day, with FDR’s approval, Arnold became chief of the Air Corps and was promoted to major general. He had gotten his chance to “straighten out the Air Corps.”

Arnold’s “longhairs” conclave two months later kicked off multiple projects. Not every seedling he planted bore fruit, but he spread the fertilizer of research and development funding far and wide. MIT, already working on radar, would keep to that task and take on windshield and wing deicing. Kármán’s shop would work on jet-assist takeoff systems for heavy aircraft.

Always driven, Arnold drove himself harder. “His idea of a good time was to work all day at the office,” his personal pilot, Eugene Beebe, said. “Then we’d rush out to Bolling Field, jump in a plane, and fly all night to L.A…, arrive in the morning, visit five aircraft factories, and then go to someone’s house for dinner that night.”

Arnold constantly preached more and better airpower and technology. “America owes its present prestige and standing in the air world in large measure to the money, time, and effort expended in aeronautical experimentation and research,” he told a January 1939 meeting of the Society of Automotive Engineers in Detroit. “Our future supremacy in the air depends on the brains and efforts of our engineers.” But brains and effort had to compete with practical tasks. Arnold shied away from what some called Buck Rogers stuff, like jet-powered planes. He agreed on the need for aircraft capable of 500 miles an hour, but cautioned in Detroit that “it will be many years before…rocket or jet propulsion can be expected on a large scale.”

Pounding industry, government, and the military for more planes and more pilots got Arnold in hot water. He bristled at moves to sell American-made planes to France and England, pitting him against Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau and even the president. Roosevelt was so irked at Arnold’s barking that the general spent months in the White House doghouse. After Arnold testified to Congress on the death of a French pilot killed testing an American plane, FDR told his air chief he had places, such as Guam, to which he could assign officers who didn’t “play ball.”

Eventually seeing how Allied deals were hobbling the Air Corps, Roosevelt came around. To make amends, he invited Arnold to dinner, with a private chat beforehand. FDR offered to make him an Old Fashioned. “Thanks, Mr. President,” Arnold replied. “I haven’t had one for about 20 years but I assure you I’ll enjoy this one with you tremendously.” Amity restored, the two worked together smoothly.

The day Germany invaded Poland, Roosevelt named Arnold’s long-ago Luzon neighbor George Marshall as army chief of staff. The trust in which the generals held one another lasted to the end of their lives. Arnold saw in the Blitzkrieg confirmation that “our worry about the German Luftwaffe had been well founded.” The Air Corps had to get the most planes with the greatest capabilities flying as quickly as possible. Scientists and engineers were to improve and perfect the B-17, an even bigger heavy bomber—the B-29, long-range fighters, and other aerial weapons also in the pipeline.

The Air Corps got a nominal promotion in 1941 to the Army Air Forces as Arnold continued his 12-hour-plus days, traveling to factories, fields, training facilities, wherever necessary. Lend-Lease business put him face to face with the future. On a trip to the United Kingdom, Arnold visited Power Jets, a company at work on a revolutionary power plant engineer Frank Whittle had conceived in the 1920s. The sight of a plane rolling down a runway with no propellers flabbergasted Arnold—and dismayed him, because the first jet-powered aircraft had come not out of an American workshop. “As far as I knew, no such device had yet advanced beyond the drawing-board stage here in America,” he recalled. “I saw this propellerless plane taxiing around the air field and making short flights. I knew then and there I must get the plans and specifications of that jet plane back to the United States.” His shock went beyond jealousy. “If the British had jets in production,” he reasoned, “the chances were good that the Germans did also.”

The British agreed to collaborate. Arnold talked with Bell Aircraft and General Electric about Bell building a plane and GE an engine. GE wasn’t ready. No problem: Arnold borrowed a Whittle as a model, and work began on the XP-59 Airacomet, shrouded in secrecy, right down to a dummy propeller for disguise. “My God, General, how do you keep the Empire State Building a secret?” Arnold’s military liaison asked. “You keep it a secret,” Arnold snapped. On September 30, 1942, the XP-59 debuted at Muroc Army Air Field, California, but remained under wraps until January 1944, when newspapers ballyhooed a new “rocket plane.” The jet had no functional range and never saw action, but, with its German cousins, it was to usher in a new era of aviation.

The XP-59 episode embodied Arnold’s flexibility. Adamant in 1939 about not pursuing jet aircraft, he saw the Whittle engine two years later and instantly pivoted, pushing jets with all he had. He knew the first one would never fight, but also that the United States had to get a jet aloft.

In another advance, Arnold had noted how the British and Germans made effective use of incendiaries. The U.S. had nothing comparable. He corralled ordnance and chemical warfare experts, along with MIT’s Vannevar Bush, who mentioned a mixture of soap and gasoline that stuck to and burned whatever it touched. The incendiary, called napalm, became a horrifically effective weapon in both theaters. Jet-assisted takeoff proved a worse bet. Kármán showed how to make it work, but Boeing’s speed at getting out the B-29 left the rocket-assist program in the dust.

Arnold’s hard-driving habits began to catch up with him. In February 1943, after a hair-raising night flight over the Himalayas to China and the rigors of the Casablanca conference, he had a heart attack, the first cardiac event serious enough to put him in the hospital. Army regulations dictated retirement, but Roosevelt waived the rules, provided he got monthly reports on Arnold’s health. A month later Arnold’s heart went into distress again; against Marshall’s advice he left Walter Reed Hospital to address the West Point class of 1943, whose ranks included his son Bruce.

Arnold felt flak and fighters were costing the Allies too many crews over Europe. To win a war, he observed, one must “try and kill as many men and destroy as much property as you can. If you can get mechanical machines to do this, then you are saving lives at the outset.” He leaned on his scientists to improve remote guidance and piloting systems.

Angling to make innovation practical, Arnold remembered his World War I project with Charles Kettering, and set the Kettering Bug’s inventor to work on a “glide bomb”—a cheap, unmanned craft that bombers could launch from hundreds of miles away. Controlled by radio and a new technology called television, glide bombs had success, but proved inaccurate and were sidelined. Another Arnold concept, Project Aphrodite, repurposed 24 worn-out B-17s and B-24s as guided and sometimes unguided weapons crammed with explosive and steered toward enemy territory. Pilots bailed out, sending planes on autopilot or remote control toward their destinations. Of more than 20 Aphrodite missions, all but one failed.

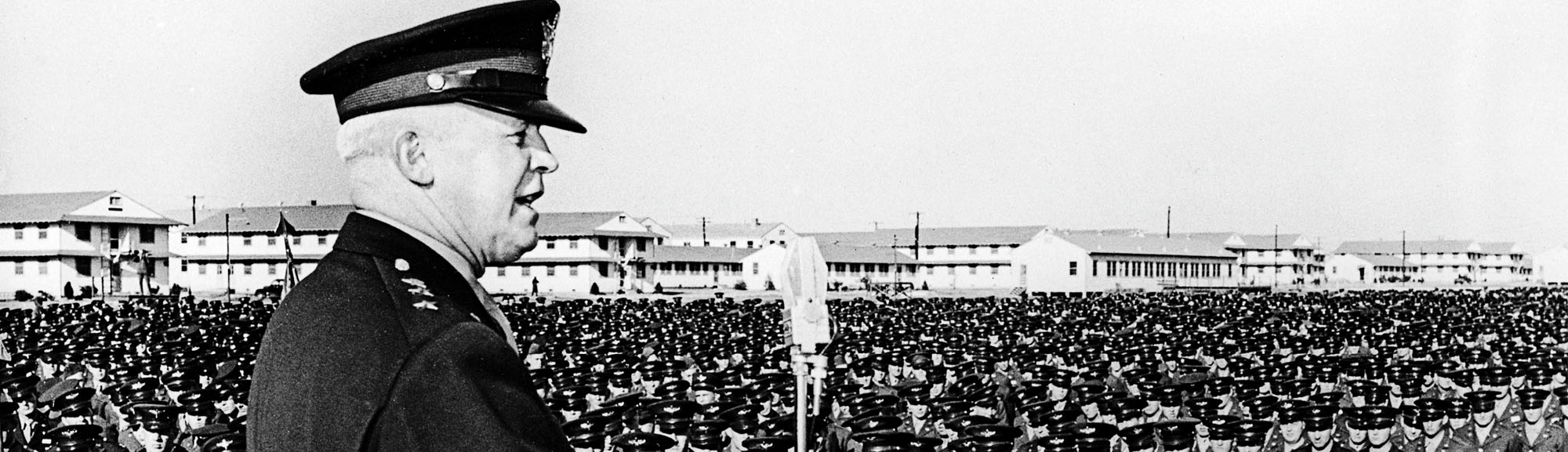

In the Pacific, Allied conquests were close to putting the new B-29 Superfortress within range of Japan. But as of January 1944, Boeing’s Wichita plant had put only 16 Superfortresses into the air. The bottleneck drew a vexed Arnold to Wichita in March. “I was appalled,” he said. “There were shortages in all kinds and classes of equipment. The engines were not fitted with the latest gadgets; the planes were not ready to go.” Arnold ordered Major General Bennett E. Meyers to Wichita, authorized to act as needed to get B-29s flying. Work stopped on everything else. Technicians and parts streamed from everywhere. Shifts went around the clock despite blizzards. Certain that the big plane needed its own unit, Arnold created the Twentieth Air Force, with himself as commander and subordinates in the field maintaining operational control.

A month after the first B-29s headed for the Pacific, Arnold had another heart attack. He rested a month before traveling that summer to Europe. Seeing that the Allies enjoyed near-total air superiority there, he again began looking ahead.

On a windswept fall day in New York, he and Kármán met in an army staff car parked out on a runway at LaGuardia Field. This war was ending, Arnold said. What about the next one? What would airplanes be like in 10, 20, 30 years? How would radar, jet propulsion, atomic power, guided missiles figure? He invited Kármán to the Pentagon to draw a blueprint for air force research. The Caltech wizard hesitated, but went on to lead a study group that wrote Toward New Horizons, a report influential not only on the air force but aeronautical science in general. It was typical Arnold: address the practical and immediate without forgetting the big picture. Once he had the present more or less under control, he resumed anticipating new problems and prospects in science and technology.

As 1944 was ending, Marshall and Roosevelt, who had awarded Arnold a fifth star, were pressing him for a firebombing campaign against the Japanese home islands. Twentieth Air Force field commander Haywood S. Hansell Jr. balked at dropping incendiaries, which he saw as immoral. A furious Arnold replaced Hansell with General Curtis LeMay, who was itching to burn Japan. Less than two weeks later Arnold’s worst heart attack yet laid him low. He turned the Twentieth Air Force over to LeMay and spent the war’s final months making inspection tours in both theaters.

Arnold retired in 1946 as America’s only five-star air force general, a distinction he still holds. In January 1950 he died at 63 of a fifth heart attack, leaving a unique legacy as the man who won the air war in World War II, the architect of the technological air force, and a visionary who guided American military airpower from its earliest days into the atomic age and beyond.