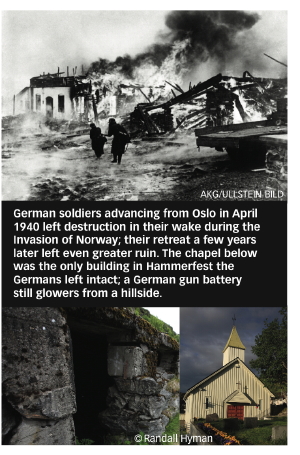

Nazi Germany invaded Norway on April 9, 1940, attacking by sea and air from Oslo in the south to Narvik some 700 miles to the north. Two months later Norway surrendered and from then on was occupied by almost 300,000 Wehrmacht troops until the war’s end. The resulting losses were devastating—especially in Finnmark, Norway’s northernmost and largest county, situated some 1,200 miles from Oslo.

The occupying German troops forcibly evacuated the population of Finnmark in the autumn of 1944, and on October 28 Hitler ordered a scorched earth policy that would leave the area devoid of shelter and supplies for the advancing Soviet forces. That winter, Finnmark, an area larger than the country of Denmark, was burned to the ground.

One of the cities that ceased to exist was Hammerfest, the oldest in northern Norway. The small fishing village, chartered in 1789, was no stranger to adversity: Hammerfest was attacked by Britain in 1809, razed by a hurricane in 1856, and then flattened by fire in 1890. But nothing could have prepared its people for the five years of Nazi occupation that culminated in the city’s destruction.

After a two-hour flight from Oslo to Tromsø this July, I was on a 45-minute hop on a Dash 8 turboprop from Tromsø to Hammerfest, and I was anxious. It had been 65 years since the ash was swept away and people had long since rebuilt their colorful homes and their lives. As the small plane flew over the snow-streaked mountains then slowly descended over Hammerfest’s 9,200 residents, I wondered which of them would be willing to open up to me about so dark a past.

I didn’t have to wonder long; Knut Arne Iversen, general manager of the tourist office, knew I had traveled to his hometown—some 300 miles within the Arctic Circle—to learn about the war. “It is in our culture to take care of guests coming so far,” he told me, putting me in the hands of his 70-year-old father, Knut Audun Iversen.

To understand Hammerfest’s past and present, the Museum of Reconstruction is the place to start. I was worried about bringing up painful memories with the senior Iversen—who was five years old when his family returned to Hammerfest in 1945 after fleeing to a town to the south—but his openness when we met at the museum was disarming. He sat me down at a table in its café and read a list of the war statistics for Finnmark.

In 1944 there were 11,000 houses, 4,700 cow sheds, 106 schools, 27 churches, and 21 hospitals burned. The list went on. “There were 22,000 communications lines destroyed, roads were blown up, boats destroyed, animals killed, and 1,000 children separated from momma and poppa,” he told me. When it was over, more than 70,000 people—the county’s entire population—were left homeless.

This tally of casualties, the first detailed account I’d had of Finnmark’s destruction, fueled my desire to grasp what Hammerfest had endured. As we got up to enter the museum, Iversen pointed out the window to what he called a “12-meter style” home, designed to house three families because of the housing shortage during the reconstruction period.

“Refugees from Somalia, Sierra Leone, and Ghana, where they always have war, are the ones living there now,” he said.

At the exhibit entrance we stopped at a piano that belonged to Ole Olsen, a renowned 19th-century Norwegian composer and poet from Hammerfest. Iversen opened the top to show me its Nazi serial number, then put his clipboard on the bench and softly played a few notes.

Throughout the occupation, Hammerfest was used as a central supply base for German U-boats attacking Allied supply convoys to Russia. The Germans enforced their stranglehold on the town with some 4,000 mines and numerous antiaircraft guns, while throwing locals out of their homes to accommodate the 400 to 500 Wehrmacht troops in search of living quarters.

In the autumn of 1944, a Red Army offensive aimed at driving the Germans out of the Arctic forced them from Finland and back into Norway. This marked the beginning of the long German retreat—and the forced evacuation of the citizens of Finnmark. On October 25, the Red Army occupied Kirkenes, a small mining town bordering Russia; shortly after that, Hitler ordered Finnmark’s destruction. On February 10, 1945, the destruction of Hammerfest was complete and the Germans pulled out. Only the graveyard chapel was left intact.

In the autumn of 1944, a Red Army offensive aimed at driving the Germans out of the Arctic forced them from Finland and back into Norway. This marked the beginning of the long German retreat—and the forced evacuation of the citizens of Finnmark. On October 25, the Red Army occupied Kirkenes, a small mining town bordering Russia; shortly after that, Hitler ordered Finnmark’s destruction. On February 10, 1945, the destruction of Hammerfest was complete and the Germans pulled out. Only the graveyard chapel was left intact.

Despite threats of death, some 25,000 people throughout Finnmark avoided evacuation by hiding in caves and mountain huts during the winter of 1944–45. After the war ended, the government imposed a temporary ban on returning because of the risk of landmines, but the people didn’t wait, and in the summer of 1945 evacuees began going home, to nothing—or next to it.

Many people had tried to save belongings by burying them in the ground before they left. Two red silk upholstered armchairs, recovered after the war and later donated to the museum, were one such lucky find. Another exhibit there shows a child’s christening gown decorated with lace swastikas, worn by a child born to a Norwegian woman and a German soldier.

The elder Iversen told me of a treasure he’d found at his home: a crystal bowl. A few days before I left Hammerfest I took him up on his offer to show it to me. As we sat in his apartment and enjoyed open-faced gravlax and scrambled eggs sandwiches, a Norwegian favorite, he told me its story.

“After we came back in 1945 we eventually built my childhood home up again, which is when I found the crystal that momma and poppa got as a wedding present,” he said. “I was five and I was helping my poppa sweep when I found it and he said to take it easy.”

As Iversen kneeled down to open the door of a wooden cabinet, pulled the small, flare-edged bowl out, and held it upward by its stem, I, too, wanted to tell him to take it easy as I marveled at the survival of something so fragile.

Another remarkable survivor stood opposite the museum: the graveyard chapel. As the museum’s curator, Kristian Skancke, explained while we talked in front of it, “The Germans usually left buildings within the boundaries of graveyards. Maybe it was respect for the dead or fear for the dead, though nothing of this is confirmed. These were the only four walls in Hammerfest after the war.”

Besides the cemetery, only two official plaques recall Hammerfest’s war dead: one inside the post office and another outside the town hall. Otherwise there are no World War II monuments in Hammerfest, but German gun batteries and bunkers remain in the mountains overlooking the city.

My only clues as to their whereabouts came from sketchy descriptions I’d gathered on the Internet, so Skancke’s offer to show me one was welcome. He guided me along a worn dirt path up a short mountain stretch to a protrusion of concrete and rock built into the hillside: a gun battery. After 70 years, this vestige of the war, which Skancke said was built for the Germans by Russian and Serb prisoners, still exuded a malignant presence.

My only clues as to their whereabouts came from sketchy descriptions I’d gathered on the Internet, so Skancke’s offer to show me one was welcome. He guided me along a worn dirt path up a short mountain stretch to a protrusion of concrete and rock built into the hillside: a gun battery. After 70 years, this vestige of the war, which Skancke said was built for the Germans by Russian and Serb prisoners, still exuded a malignant presence.

As I grew acclimated to Hammerfest’s barren landscape, so typical of Arctic geography, it became clear there was still something extraordinary about this far northern town that rose from the ashes of war like a phoenix. It isn’t the eclectic mix of rustic charm, trendy cafés, and contemporary buildings on the scene. It goes beyond the town’s homogeneous look from the reconstruction period. Those modern buildings belie Hammerfest’s true age and the source of its power: the town’s centuries-old “family tree.”

“It’s far away from the rest of the world. People live here for the roots,” the younger Iversen had said to me when I first arrived. After several days digging up the past I’d glimpsed roots that ran far deeper than any fire could ever reach. Hitler’s scorched earth policy was no match for the people of Finnmark’s love for their land.

There were no fireworks on July 4th during my visit, just the midnight sun that glowed over this little town at 70 degrees north. The rise of Hammerfest was celebration enough for me.

Susan Zimmerman is a freelance writer who lives in St. Louis, Missouri. Zimmerman has a keen interest in Norway, and has written about Svalbard, the Lofoten Islands, and Bergen; those stories drew her to the country’s northernmost region of Finnmark to recount the dramatic story of a town’s survival after the Germans reduced it to ashes.

Color photos by Randall Hyman.

When You Go:

Hammerfest, located on Kvaløya Island, is the northernmost city in the world. Fly into Gardermoen International Airport in Norway’s capital city of Oslo, take a morning flight to Tromsø, and then a connection to Hammerfest on Widerøe Airlines (wideroe.no).

Where to Stay and Eat

The Rica Hotel has great harbor views and is a convenient five-minute walk from the Museum of Reconstruction and the graveyard chapel. The Rica’s restaurant, Skansen Mat og Vinstue (which serves reindeer fillet and whale steaks), is highly recommended. Nearby Qa, a cozy café at the harbor, has great lattes and atmosphere.

What Else to See

Hammerfest has plenty to keep visitors busy day and night, especially from mid-May to mid-July during the midnight sun: there’s the Meridian Column (erected in 1854 in memory of the first international measurement of the Earth’s circumference, it was taken to Trondheim during the war and brought back in 1949); the Skansen open air museum (a defense fortification built during the Napoleonic Wars in 1810, it has a cannon and two old buildings); Sørøya Island (a short boat ride away, where some 1,000 locals hid in caves during the war); and Forsøl fishing village (a picturesque spot about five miles from Hammerfest with Stone Age sites and rows of fish drying racks almost a football-field long). And there’s a chance you might see a reindeer; some always wander through town as thousands migrate to the coast in summer.