In his new book, “Never Panic Early: An Apollo 13 Astronaut’s Journey” (Smithsonian Books, 2022), Fred Haise, known to the world for his role as the lunar module pilot in Apollo 13, writes about his career in aviation, including his time as a test pilot at Edwards Air Force Base. Aviation History magazine contributor Doug Adler talked to Haise about his book and his career. (To watch the interview, scroll to the bottom.)

you’re known around the world as an astronaut. But after reading your recent autobiography, one gets the impression that you view yourself really, first as a pilot and an astronaut second. would you agree with that?

Yeah, I think all of us at that time, we were primarily former military pilots. Most of us had been in the astronaut business, and with aircraft tasks and so from that, we joined the astronaut program. So, you know, our primary livelihood for years had been with airplanes. And it really, to me, people don’t realize, they think space is something extra special. But a spacecraft is just an airplane with a few different kinds of subsystems because it operates in a different environment. And it has rocket engines versus a jet engine. And so the practice you do—although I have to say Apollo was a huge program, with 400,000 people at peak, so it was bigger than most aircraft test programs I was involved with, as far as the number of players—but the principles involved were all the same. Obviously we had an endpoint with Apollo that was pretty exciting to think about—going to the moon. But other than that, I mean, people don’t understand it. But to me, it was just another exciting adventure.

the section about your initial flight training as a young man, your early naval flight assignments — it’s written with enthusiasm. was this the most enjoyable period of your time as a pilot?

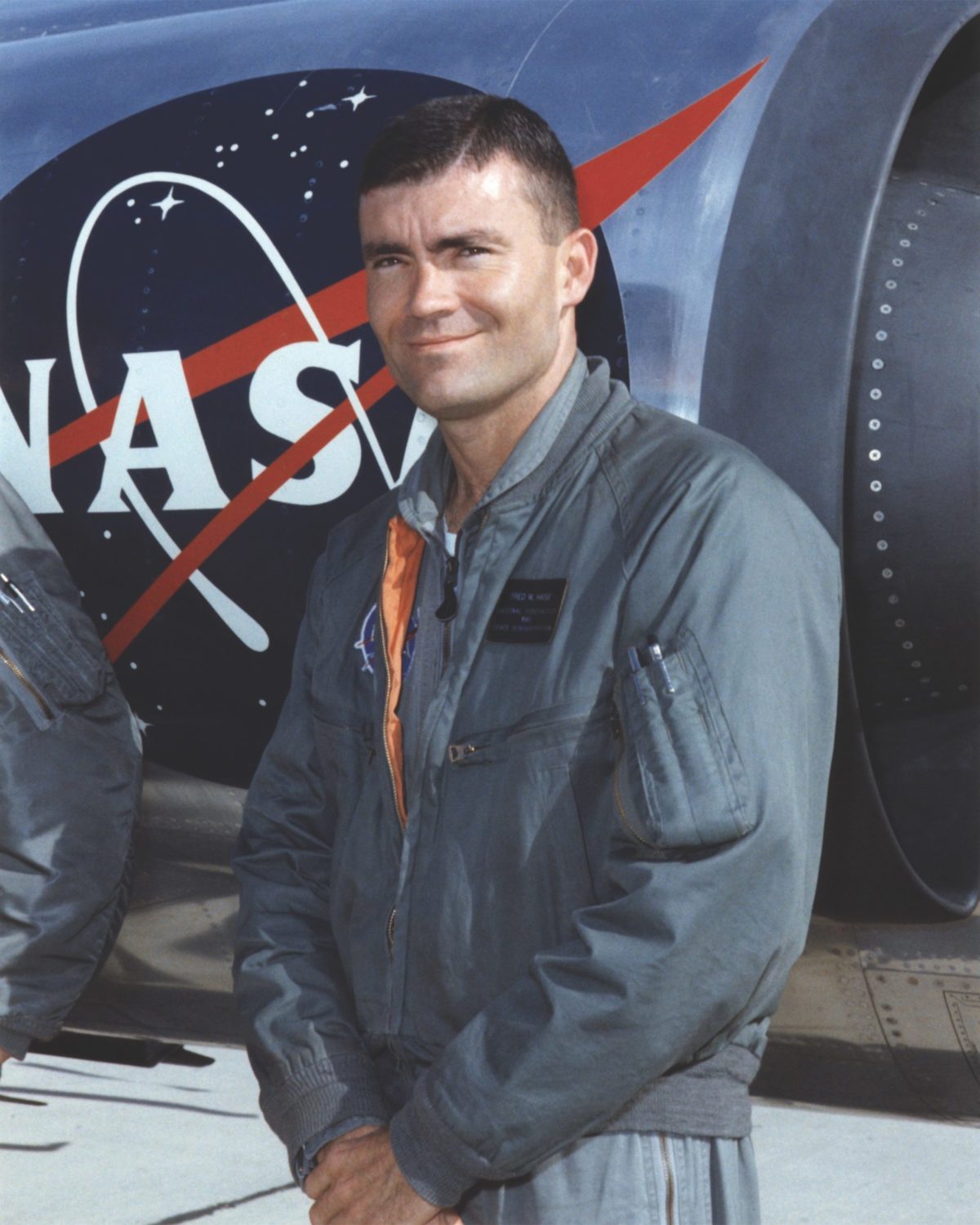

No, no, I’d have to say the most fun time of my career was when I was at NASA Flight Research Center, now named Armstrong, at Edwards, as a NASA test pilot. And because I was involved in so many different things. I probably was involved in three test programs at any given time, sometime only the prime pilot in one test program, I’d be one of the evaluation pilots for handling qualities or something like that on another test program were on, and then I did support flying a lot for the X-15 that was going on at that time, either be a chase, or do the morning weather checks, or go check the upper range the lake beds ahead of time to see if they were safe or if they had the drop in early and check telemetry stations up range at Bailey and Ely, that kind of thing. So probably flying, not every day, twice, but sometimes twice a day, but almost flying every day.

I imagine that flying at Edwards in that period, you must have felt like you’re at the absolute peak of the flying game.

Yeah, it was right at the end of what I call a golden era of aviation tests at Edwards.

You mentioned in the book that it was when you were at Edwards, you decided to apply to NASA to become an astronaut. Did you think it was a long shot?

No, I thought I thought I had a good chance. I had done — call it my servitude and getting the background experience. My resume I thought was solid. I had to think hard about the flying. I almost really thought several times whether I should do that and leave the good flying I was doing because Neil — Neil Armstrong — who was ahead of me about three years with NASA, he joined at Lewis Research Center ahead of me, and then he went to Flight Research Center, and then on into the astronaut program, came back and described his job as an astronaut as sitting in a lot of meetings, sitting in a simulator a lot — lots and lots of hours — and not much good flying. So that was Neil’s description of being an astronaut, which was pretty close to being right. And so I had to think hard about leaving all this good flying and joining the astronaut program. But the thought of getting to the moon was overpowering. So that’s why I did.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our Historynet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

In the book, I get the sense that you wish you’d had a chance to fly the X-15.

Yes, yeah, the X-15 is the last space vehicle that the pilot has manually controlled the flight from the time they released from the B-52. They got the engine going. But very quickly had to do a very critical and accurate pull up to a certain attitude that basically reflected the profile that we’re going to fly, just as the rocket has to get to the asset attitudes to go to orbit. And so all manual, there is no autopilot in the X-15, and then they had to change somewhat the flight controls, they went up high over the top because the aerodynamic controls were no longer active, so they had to use little gas rockets to control attitude. And then the setup for a very critical entry, to be set up with the right angle of attack and attitude for when they came back into the atmosphere. They were going fast enough there was heating to deal with and manually all the way through that and setting up and controlling through the entry, then to come out of that at the bottom and from a navigation standpoint to arrive back over Edwards and do a circular kind of approach overhead to affect the landing. All manual at Edwards, with an L over D of about a four and a half. About the same with the shuttle.

So, it’s a manual vehicle and apart from the rocket business, from Mercury on nobody has ever flown an ascent. Only all pilots, I should say astronauts, could do the aborts, but that was the sort of the extent of their capability. You just hope, we all hope, this rocket had been prepared right, and it was fully gassed and that would get us up there. But you are along for the ride. You monitored, of course, how it was doing on the way up should you have to abort. But there was no manual control at all. Through all the ascents.

many astronaut autobiographies have commented that Chuck Yeager was maybe less than enthusiastic about losing people from Edwards to NASA. What was your experience with him overall?

No, I never saw that in Chuck. He was obviously commandant at the test pilot school when I went through for a year and as you know from the book, I shouldn’t have gone through the second half of the school. I was the first civilian ever to go through the second half. Chuck arranged that, actually didn’t arrange it, he said let’s just come on and I’ll get into school and somewhere down the road he decided to tell the Pentagon people he’d had done that. And so I got to go through the whole year rather than the first six months. Which normally test pilots could do, just test pilots would do. And so he was very gracious that way. I flew with him. I described that in the book because I did a little showing off while I had Chuck beside me there in the airplane while we were chasing a lifting body.

Recommended for you

You told him you were worried about over stressing the engine a little bit so you shut it down. Correct?

Right. The batteries we had were the older acetate batteries rather the newer ones, so I just kiddingly said I didn’t want to stress the batteries.

The book is titled “Never Panic Early.” what does that phrase means to you?

I think it deals with everyday things for people, in their home if their child has all at once a problem, an accident or something, then they have to mentally go through a process of figuring out what’s the best thing to do. In some cases, do I call a 911 first or get an ambulance or call and ask for help from a neighbor? Or do I try to patch the child up in some way myself? So on occasions for people who have that same dilemma of trying to think through the situation and all the options they might have of what to do, and primarily, don’t do anything too quickly where you might do the wrong thing. Think first.

“Never panic early” has served you well in a variety of situations.

Absolutely. Yeah. I’ve experienced that in airplanes, where you have a system problem and rather than throw any switches or do anything, you normally will study the instrument panel. And think about your knowledge about the system. And what if it’s real or not, for sure, it’s not something false. And then next is the procedures, do you know the system, and then emergency procedures? Now function procedures on what steps you now should take.

Most astronaut biographies describe the astronaut office in Houston, to put it mildly, as an extremely competitive environment. Your book didn’t really do this. what was your experience like?

No, I didn’t find that at all, at least among the group, the original 19 that were chosen in 1966. Frankly, I wasn’t in the office that much. Initially, because after rookie training went on, supposed to go on, I think it was originally 12 months or 15 months. They cut it short at about nine months because we got support crew assignments, there was so much work to cover. And I got assigned to follow the lunar module in testing at Grumman, I and Ed Mitchell. And we were up there for a good part of a little more than a year. So I wasn’t back in the office to see people that much anyway, and I just off on a mission for Jim McDevitt that we were dispatched to make sure he had a good lunar module to fly when he flew Apollo 9, with LEM 3, although we tested I was in from LEM 2 through LEM 6. I was in those vehicles the first time we put power on and getting those ready to get ready to go to the Cape.

Perhaps the fact that you were up at Grumman for so long spared you some of the more tense experiences that other astronauts write about?

No, I never felt competition. I obviously didn’t know and hoped I’d be chosen early. But I had no idea. And none of us knew how exactly the process was going to be in selecting who would get what missions and when. We knew obviously Deke Slayton and Al Shepard, were at the front end of that. And as it turned out, later, we found out that whatever they did, which I guess was rubber stamp most of the time, was actually sent to headquarters before any announcement of that.

I’ve always been curious about life after the mission [apollo 13]. what was it like to return to the astronaut office after coming back from that mission?

Well, we of course, we had public affairs events. In fact, we made the first state department, well, that was sort of a quarter-world tour through Iceland, Ireland, Germany, Switzerland, and the first official group to go into Greece. That was after the colonel had overtaken the country and kicked the royalty out. And so, we were tied up with that, although within about a month or six weeks, Deke called me in and I had my next job assignment. I knew that we were going to be, I was going to be the backup commander for Apollo 16. So, for me, it was just back in crew training again as soon as they got rid of the public affairs business, with Jerry Carr and Bill Pope.

Never Panic Early: An Apollo 13 Astronaut’s Journey

by Fred Haise and Bill Moore, Smithsonian Books, April 5, 2022

If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.

And your backup position on Apollo 16 put you in a prime slot for Apollo 19, had it occurred.

Had it occurred, that’s right.

You write with a lot of excitement about the approach and landing tests [ALT], the captive and the free flights. These tests were absolutely vital to the success of the shuttle program. how does it feel looking back on the ALT test today as essentially the de facto first person to ever land a space shuttle?

I look back at it as really the highlight of my career. You see, before I got involved assigned as a crew, I had spent four years in the Orbiter Projects Office. So I was in management, in essence, and I was following the design and development of that orbiter that was in the Orbiter Projects Office. So, I was kind of a womb to the tomb experience because actually, I was on a group that evaluated the proposals for who submitted the cut companies as submitted those to pick even who would build the shuttle, which I didn’t advertise much later.

But anyway, so I was there from day one on space shuttle orbiter, at least involvement, and then get to fly it the the first time. It was a program also that was off to the side of the major program. We were given limited assets. Deke Slayton, who I greatly appreciated, actually left his position and became the test director. So really it was back to the aircraft flight test program at Edwards. And he had an accomplice, the number two guy, who had been at Edwards flight test before in his career. We had a good team that came out from Kennedy early, which they’ve never done before. They always sent a few people to the factory previously on vehicles and witness some tests, but they never had hands-on until the vehicle got to Kennedy. But I talked him into going early on this one to get some experience. And they did, we had the very best from Kennedy. And we had a top Rockwell team that was left over from Apollo days of test conductors and test engineers. So we had a Grade A team, but a very small nucleus set off while the rest of the world was worrying about how to go to orbit, in Columbia. So, it’s kind of a neat program in that sense. We’re off to ourselves.

We had two support crew members assigned, Bob Abopco and Overmyer, Bob Overmyer. And we actually had to borrow some talent, steal some talent, with others to help with the software job, which is the biggest job, most probably, to get it flying. Enterprise was also a big programmatic thing for NASA at the time. As we went into that program, NASA had had had to announce a several years’ slip in the orbital flight because of the tile problem. We also faced a new president having come in and it wasn’t his program. It was Nixon’s program. And President Carter had come in. And so, we worried about those aspects. We had no backup. We had a second Enterprise when we started the program. But quickly for cost — the program costs were cut early — we deleted it, so we had no backup vehicle. You don’t like that situation in a test program.

And, and there was obviously time pressure, because at the time there was potential hope of saving Skylab.

Right. Yeah. Skylab was pretty easy to avoid, actually, because it flew in 75. And first orbital flight at that time, early on was, I forget what it was predicted initially, I think ’79. And they had they acknowledged that slip to ’81.

You said something that I thought was really striking in the book. the space shuttle is carried aloft aboard a modified 747, And you said that the flight, for example, when the shuttle was released was actually more dangerous to the crew of the 747.

Absolutely, yeah. Yeah, we were on top of the 747, and had we gone out of control at release, had we damaged the 747, that crew could not have gotten out. They had no escape system, whereas myself and Gordo Fullerton, we were sitting in ejection seats. So we had a plan B that hopefully would have enabled us to survive. But Fitz Fulton and Tom McMurtry and Vic Horton and Skip Guidry would have all died had we seriously damaged that 747.

unfortunately, NASA’s Artemis program seems to be creeping forward at a pretty slow pace these days, whereas SpaceX, Virgin Galactic, Blue Origin and the other private space programs are making rapid progress. What are your thoughts on private spaceflight?

Well, private spaceflight, for the most part, at least, Space X is quite mature, particularly at this point. So, they’re almost able to live off the income earned, including what NASA pays them for the ride. And the rest of Artemis NASA has to deal with. Still as depending on the same old problem of getting the budgets cleared through the subcommittee and mainly the House has always been the bigger problem for NASA to deal with, because it’s such a big change out of people. Coming up is midterms and there’ll be a lot of new people that NASA has never dealt with before now entering those committees, to call it re-educate about what Artemis is all about and why it’s worthwhile. But truly, NASA has never had a program with the same, I’ll call it national-level impetus, administration and Congress combined, as Apollo had. There’s never been another program like that.

it’s been very impressive to see how quick they’ve moved, especially Space X. And Space X is very far along with their heavy lift booster. It will be very exciting to see where that goes, I think.

It’s incredible the number of launches they’ve done and then I like their re-use. One booster has flown that first stage has flown five or six times.

Extremely impressive. And it really shows you that I think a lot of people scoffed at private spaceflight. And I think now nobody can scoff at it.

Yeah. Well, way back when I know some of the astronauts went up and made a plea at Congress. They plea was misunderstood, though, and the press took it wrong. What happened was the initial funding that was done, which was needed, because SpaceX had problems early on, had a couple of failures. And they were about running out of worthwhile money to employ if that continued, and NASA gave him I forget how many, a billion plus, and Neil, I think, and [Eugene] Cernan, I think Lovell even went to testify. What they had done though was they gave that money to Space X, which was rightful, but they made NASA eat it, in other words they made NASA take it out of the rest of their budget. In other words, they didn’t give them a Delta in their budget to take care of that. And that’s what I think they were complaining about because it doesn’t just impact the manned space part, it also impacted some of the unmanned programs that had a program plan based on certain funding levels, annual funding levels, so it kind of set them back too.

And it caused a bit of a dust up, although I think Cernan walked back a lot of the comments.

Yeah. I don’t think they thought they’d be a failure, at least I don’t think. I think the main argument they had was they should have given NASA the Delta budget that they then could have given to SpaceX to get started. So going there.

I think we’ll all continue to watch it with great interest. Fred Haise, I want to thank you for taking the time to do this interview.

All right, thank you and fly safe.