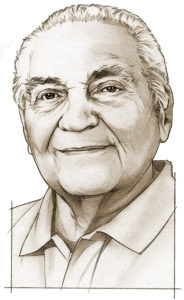

Eight decades ago Guy Prestia helped battle fascist Italy and Germany in World War II. Today the 98-year-old veteran visits schools near his hometown of Ellwood City, Pa., some 35 miles northwest of Pittsburgh, to detail his experiences as a soldier in the U.S. Army’s 45th Infantry Division. Prestia served as a sergeant in Company E of the 157th Regiment under Capt. Felix L. Sparks, subject of The Liberator, an Alex Kershaw book and adapted Netflix series. Prestia and his “Thunderbird Division” comrades fought in Italy and from southern France across Europe to the dreaded Dachau concentration camp. Though COVID-19 has curbed his schedule, Prestia remains on a mission to relate the sacrifices the Greatest Generation made to preserve liberty.

What prompted you to share your wartime experiences?

I began in 2001 when my granddaughter Chelsea was in the sixth grade. Her teacher said something about the war, and she said, “My grandpa was in World War II! He even has an Iron Cross from a German soldier.” A few days later the teacher called me and asked if I would speak to the children. Once I did that, somebody put my name in the newspaper, and I got calls from different schools.

I always save time for the kids to ask questions. I learned a lesson early on, though. There was a little girl who asked me, “How did you feel the first time you killed an enemy soldier?” That hit me real hard. I just said, “It made me sick. Next question.” From then on I would have the kids write their questions down on a piece of paper so I could screen them. There are things that are just too graphic. You can’t blame the children. They are just curious.

I have a lot of artifacts I bring: medals, photographs and my uniform, even though I can’t wear it anymore. I lay them out for the kids to see. I show them the Iron Cross and the Presidential Unit Citation my unit got at Anzio. I also have letters and cards from my company commander, Felix Sparks. I even show them my French Legion of Honor, which I got last year.

‘Dachau was a bad place. We were not prepared for anything like that. We liberated the camp on April 29, 1945. We found these railroad cars. I think there were 39 of them. From a distance they looked like they were filled with logs, but as we got closer, we saw they were emaciated bodies. There were more than 2,000 dead. It was horrible’

Where did the war take you?

My outfit was in combat for 511 days. The 45th Division was a Western unit that started in the National Guard with men from Oklahoma, Colorado, Arizona and New Mexico. As they moved east during training, they started adding others to the division. I joined in May 1943 before shipping overseas. We landed in Sicily during Operation Husky. I carried a Browning automatic rifle. It was heavy, weighing 21 pounds, and when you put your finger on the trigger, you got rid of those 20 rounds in 2½ seconds.

What do you remember about your time in Sicily?

We were in bivouac outside of Palermo, and we could see down into the town. There was this street with one big building—a hotel. A Stuka dive bomber attacked the hotel, but he was too quick when he released the bomb. It went into the road and made a big crater. Well, the next morning we found out that in that hotel were Bob Hope and his troupe, including singer Frances Langford and guitar player Tony Romano. They were there to put on a USO show for us, which we saw a few days later. They didn’t have to be there. They came over to entertain us. I remember seeing actor George Raft, comedian Joe E. Brown and former heavyweight boxing champ Primo Carnera, who put on an exhibition.

How did the landings on mainland Italy differ?

At Anzio we had a 30-mile beachhead. We tried to dig foxholes in the ground, and it was all water, so we had to work up to the railroads and bridges. Then we were in the caves near Anzio, where a lot of our battles were fought. We [were shelled by] German artillery and took heavy casualties. Roy Zuber was my assistant gunner. He got shot by a sniper and lost an eye. The artillery shelling was so severe, we couldn’t get him to a field hospital for three days. I got to see Roy later at a rest camp. I laughed because he had one brown eye and one blue eye. They didn’t have the right size in brown, so they gave him a blue one. They did fix it when he got back to the States.

What do you recall about the Thunderbird Division?

Felix Sparks became our company commander at Salerno in Italy. He was good, and he cared for his men. He wasn’t with us very long before he got wounded. He took shrapnel in his liver and went to the hospital but came back in a few weeks. Then he got wounded a second time but came back again. We thought, “Boy, this guy is like a cat with nine lives. You can’t knock him out!”

There were a lot of Indians and Mexican-Americans in the 45th Division. One of my best friends was Jesús Valles. He couldn’t read or write English, so I had to read and write his letters for him. Some of our Indians were from the East. You’ve heard of Van Barfoot, who won the Medal of Honor? I wasn’t far from him that day! He was a Choctaw from Mississippi. I kept in contact with him long after the war.

What was it like to liberate Dachau?

Dachau was a bad place. We were not prepared for anything like that. We liberated the camp on April 29, 1945. We found these railroad cars. I think there were 39 of them. From a distance they looked like they were filled with logs, but as we got closer, we saw they were emaciated bodies. There were more than 2,000 dead. It was horrible.

How has COVID affected your school visits?

I follow the guidelines of the experts in the medical profession. I’m held pretty tight to that, because my daughter worked at a hospital, so she’s pretty strict with that stuff. They have a vaccine now, so I’m hopeful I can get back soon. I’ve also spoken at other places, like the Rotary Club and Slippery Rock University. Lately, because of the virus, I’ve been speaking online. I even did one with Crestwood Preparatory College in Canada.

What’s your primary message to students?

We were overseas for a long time. We wondered, Why are we here? We finally determined, after liberating Dachau, we were there to set people free. I also tell them about how war changes your compassion. At the beginning you only think about yourself. That changes pretty quickly. Once you get into battle, and you see people getting hurt and killed, you get compassion. You treat them the way you want to be treated. That’s probably the biggest change in a person because of war.

You never forget the things you went through. But I was never at the point where it bothered me. I heard about others who would wake up in the night and remember the bad things from the war. I never had those experiences. I did dream about what happened, but it didn’t upset me. Some people lived that the rest of their lives. MH