‘What has not been examined impartially has not been well examined. Skepticism is therefore the first step toward truth.’ -Dennis Diderot, philosopher (1713-1784)

Old myths die hard. For example: the Wright brothers were co-equals in aviation innovation, right? Wrong. Author John Evangelist Walsh ably proved in his biography of the Wrights, One Day at Kittyhawk (1975), that Wilbur was the leader, Orville the follower-Wilbur the genius, his younger brother the junior assistant.

How did the notion that they were ‘coequals’ emerge as fact? Wilbur died in 1912. Orville, by controlling the Wright archives, influenced history. In the official biography, authorized by Orville 30 years after Wilbur’s death, the brothers came out as coequals, with Orville more often than not playing the larger role.

Another question: Who made the world’s first powered airplane flight? The Wright brothers, of course, on December 17, 1903. Or perhaps not. Some historians believe that on August 14, 1901, at Fairfield, Conn., Gustave Whitehead achieved powered flight-two years and four months before the Wrights’ first flight.

Which leads to a further question: Who was Gustave Whitehead? Many voice the view that Whitehead’s work as an aviation pioneer has yet to receive a full and objective study.

A longtime leader of the efforts to learn the truth about Gustave Whitehead is Major William J. O’Dwyer, U.S. Air Force Reserve (ret.), of Fairfield, Conn. He was a World War II flight instructor and later a ferry pilot with the Air Transport Command. In postwar years, O’Dwyer became a building contractor in Fairfield, a job that, in 1963, led to his involvement in the Whitehead saga. In the attic of a house owned by the mother of Lt. Col. Thomas Armitage, a fellow member of the 9315th Air Force Reserve Squadron, of Stratford, Conn., O’Dwyer ran across photographs of Whitehead’s 1908-1910 aerial experiments. The photos were in family albums of Armitage’s late uncle, Arthur K.L. Watson, who had helped finance Whitehead’s work in those years. The pictures bore the title ‘Whitehead’s effort’ and nothing more.

‘As pilots,’ said O’Dwyer recently, ‘we sensed that the pictures had historical significance and should be in a museum. So we took them to Harvey Lippincott, founder, and at the time president, of the Connecticut Aeronautical Historical Association (CAHA) in Hartford. Soon we learned that Whitehead’s claimed flights of 1901 and 1902 had allegedly taken place in our hometowns of Fairfield, Bridgeport and Stratford. We’d stumbled on a mystery from which we couldn’t walk away.’

Today, 30 years later and having spent a’small fortune’ on his detective work, O’Dwyer is convinced that those historians who have labeled Whitehead an empty dreamer or an outright charlatan are way off base. ‘It’s strange,’ he said, ‘that those opinions evolved without extensive research, official inquiry or probe.’

Research showed that Whitehead’s 1901 airplane-a high-wing monoplane with an enclosed fuselage and two propellers up front-was closer to today’s lightplane configurations than any built by his contemporaries. His U.S. aviation ‘firsts’ numbered more than 20. They included, to name but a few, aluminum in engines and propellers, wheels for takeoff and landing, ground-adjustable propeller pitch, individual control of propellers (to aid in directional control), folding wings for towing on roads (resulting in what was possibly the world’s first roadable airplane), silk for wing covering, and concrete for a runway. He built more than 30 aircraft engines and sold them to customers as far west as California. An earlier student of Whitehead’s life and career was the late Stella Randolph of Garrett Park, Md., author of two books, Lost Flights of Gustave Whitehead (1937) and Before the Wrights Flew (1966). Despite details, documentation and photos of Whitehead’s airplanes, gliders and engines, the books were denounced by leading aeronautic agencies, including the Smithsonian Institution and the American Institute of Aeronautics. They described Randolph as ‘unqualified’ and her books as ‘unreliable.’

In late 1963, O’Dwyer assumed duties as head of a research committee jointly sponsored by the CAHA and the 9315th Air Force Rescue Squadron. He began with eight pages of leads compiled by Harold Dolan, a Sikorsky Aircraft engineer and vice president/secretary of the CAHA. The Whitehead/Wright/Smithsonian evidence amassed by O’Dwyer now fills 20 file drawers in his home near Fairfield Center, with an orderly overflow of bulging cardboard boxes reaching from his small office into adjacent rooms. The CAHA information on Whitehead is filed at the New England Air Museum at Bradley International Airport, Windsor Locks, Conn., under the stewardship of archivist Harvey Lippincott.

To date, the total evidence, based on three decades of research, has convinced O’Dwyer and others that history has indeed been ‘tampered with.’

In addition, the record was spelled out in O’Dwyer’s book History by Contract, published in Germany in 1978, with Stella Randolph as coauthor. The book accused the national Air and Space Museum (NASM) of an apparent conspiracy of silence interspersed with behind-the-scenes demeaning of Whitehead’s efforts. The net result, O’Dwyer and Randolph alleged, made Whitehead a virtual nonentity in aviation annals.

Gustave Whitehead was born Gustave Alvin Weisskopf on January 1, 1874, in Leuterhausen, Bavaria, Germany. Growing up in the era of Otto Lilienthal, the German glider pioneer, young Weisskopf became obsessed with the idea of flying. Later, he met and corresponded with Lilienthal, learning something of the rudiments of flight.

Orphaned at age 12, Weisskopf worked his way to Brazil as a seaman a few years later. During his four years at sea, he showed aptitude for the many mechanical skills needed aboard ship. Still dreaming of flying, he studied the flight of sea birds. He also survived four shipwrecks, the last of which put him ashore in 1894 on the Gulf Coast near the Florida Panhandle.

Weisskopf wandered northward, surviving on whatever work he could find. He reached Boston in 1897 after learning that the Boston Aeronautical Society had a job opening for’someone with kite and glider experience.’ He was hired mainly because of his work with Lilienthal. Financed by the society, he built a biplane/ornithopter, a man-powered craft with flapping midwings. Not surprisingly, it failed to fly.

Weisskopf’s travels next took him to New York City, where he demonstrated kites for the Horseman Toy Company and met his future wife, Louise Tuba, a Hungarian emigr. The couple’s next stop was Buffalo, where they were married; then Baltimore, where their name was Anglicized to Whitehead. They then went to Pittsburgh, where Gustave began his efforts at powered flight.

In the spring of 1899, after finding work as a coal miner, he built a two-man aircraft powered by a steam engine. The project ended when the craft, with Whitehead as pilot and Louis Darvarich aboard as a stoker, crashed into a three-story building. Darvarich suffered lifelong scarring from steam burns and spent three weeks in a hospital. Whitehead, up front at the controls, escaped injury. It remains unclear as to whether or not the machine was airborne when it struck the building.

Whitehead, who had become unpopular with his neighbors and the police because of noisy nighttime tests of his steam boilers, which occasionally blew up with a roar, soon left town by bicycle with Darvarich. They sold their bikes in New York and continued by train to Bridgeport, Conn., where Darvarich had friends. Whitehead took a temporary job in a coal yard, then found more permanent work as a factory machinist. When his wife and daughter Rose arrived in Connecticut in 1900, the family moved into a house in Bridgeport’s West End.

Whitehead resumed his efforts at flight, working nights in his basement. Later, he used $300 donated by an enthusiastic Bridgeport resident to buy materials to build a shedlike shop in the yard of his house. Neighborhood teenagers, captivated by Whitehead and his work, became his unpaid helpers. His efforts ranged from studying tethered seagulls to reading scientific journals and Octave Chanute’s two books on aeronautics.

Whitehead gained knowledge step by step and evolved a series of gliders and airplanes, each one a modification of its predecessor. In the spring of 1901, he completed ‘Airplane No. 21’ with which, on August 14, he claimed to have made his first successful powered flight in Fairfield, then a farming and residential town just west of Bridgeport. The flight, according to Whitehead, subsequent testimony from co-workers and an article in the August 18, 1901, Bridgeport Sunday Herald, covered a half mile and included a change of direction to avoid a stand of chestnut trees, plus a safe landing without damage to the aircraft.

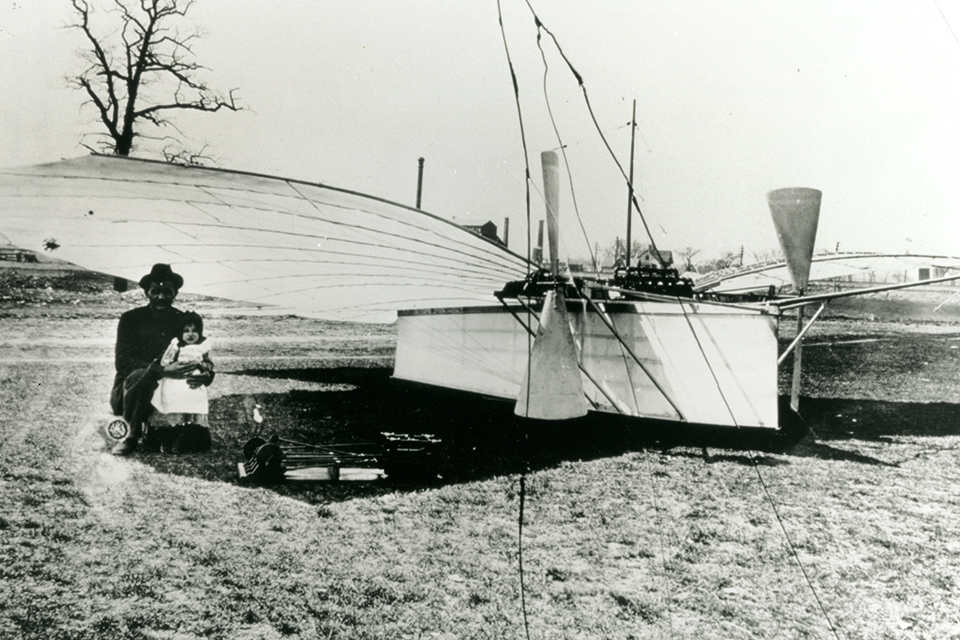

A variety of evidence, including photographs taken in 1901, shows Airplane No. 21 as an aerodynamically correct monoplane with such wing features as dihedral angle, camber and angle of incidence. The wings had no spars, but instead employed load and flight wires rigged in the manner long used in early airplanes. They provided ample support for the slow-flying craft. A ‘bowsprit’ and ‘mast’ reflected Whitehead’s nautical background, as did the boat-shaped fuselage in which the pilot could stand or sit at the control stick.

A movable horizontal tail provided up and down pitch control. For banks and turns, Whitehead shifted his weight. There also is evidence that wires may have been used to warp the wings for banking and turning. Alternating the power to the tractor propellers gave additional directional control.

Each wing had nine bamboo ribs attached to bamboo leading and trailing edges. Japanese-silk surfaces were attached on the underside of the wing structure, an arrangement that allowed the silk to billow up firmly around the ribs, thus reducing, but probably not eliminating, rib interference on the airflow over the wing. Tethered tow tests of a replica in 1986 showed the worst interferences occurred at the wingtips, where negative lift was encountered as liftoff approached. A slight change in rigging corrected the problem in the modern re-creation of the craft.

The craft had two engines-a ground engine and a flying engine. Both were fueled by the same calcium carbide (acetylene) generator. The ground engine was used for traveling on the plane’s four wheels to test sites and during the takeoff roll. At liftoff, fuel to the ground engine was valved off, with all power then going to the main, or flight, engine. The engines were’steam type,’ except that Whitehead used the expansion forces of acetylene instead of the much heavier steam system he had used in Pittsburgh. O’Dwyer cited Whitehead’s use of wheels in 1901, rather than skids, as enhancing his ‘first in flight’ claim. The Wright Flyer of 1903, with its skids, relied on a catapult and rail system to achieve flying speed.

Whitehead continued to build aircraft and lightweight engines in the ensuing decade. Having abandoned steam, he moved to acetylene, kerosene and gasoline for fuel. He advertised and sold his engines to aircraft builders nationally. A notable customer was Charles R. Wittemann of Long Island and New Jersey. Wittemann was one of the earliest (1906) designers and manufacturers of airplanes and gliders in the United States, and a builder in 1923 of the Army’s huge triplane, the six-engine Barling bomber. Whitehead appears to have reached the peak of his airframe success with the birdlike monoplanes of 1901 and 1902. Aircraft Nos. 20 through 23 were similar in design, but aluminum replaced bamboo for wing structures after No. 21. Later, seeking greater wing area to provide added lift for heavier engines, he changed to biplanes and even one triplane.

Meanwhile, the Wrights had achieved their own successful flight-and had begun taking steps to guard its place in the history books. From 1925 to 1948, the Wright Flyer was on display at London’s South Kensington Science Museum. Orville had sent it to England rather than to the Smithsonian because of his outrage at the Smithsonian’s display of Samuel P. Langley’s Aerodrome as the first man-carrying airplane ‘capable of sustained free flight,’ even though Langley’s craft had not actually flown. Langley had formerly served as secretary of the Smithsonian (see ‘Enduring Heritage’ in the January 1996 Aviation History).

In 1914, after a bitter court battle between the Wrights and Glenn H. Curtiss over which of them should be recognized as ‘pioneers in the practical art of flying with heavier-than-air machines’-which the Wrights won-the Curtiss company was permitted to take Langley’s original 1903 machine from the Smithsonian to the Curtiss test site at Hammondsport, N.Y. The intent was to make tests to justify the Smithsonian’s long-standing recognition of the Langley aircraft, thereby invalidating the Wrights’ newly won title of pioneers. The Smithsonian paid Curtiss $2,000 toward the expenses of the tests.

In the March 1928 issue of U.S. Air Services magazine, Orville Wright wrote: ‘It [the Smithsonian] published false and misleading reports of Curtiss’ tests of the machine at Hammondsport, leading people to believe that the original Langley machine, which had failed to fly in 1903, had been flown successfully at Hammondsport in 1914, without material change. These reports were published in spite of the fact that many changes, several of fundamental importance, had been made at Hammondsport.’ Twenty years later, in 1948, the Wright Flyer was returned to its homeland where it has been an extremely popular exhibit ever since. And Kill Devil Hill, N.C. (a state whose automobile license plates assert ‘First in Flight’), has become a mecca for millions of tourists and aviation buffs.

Despite rumors of an agreement between the Smithsonian and the Wright estate, an actual contract remained elusive. O’Dwyer noted that during a 1969 conversation with Paul Garber, then the NASM’s curator of early aircraft, Garber denied that any such agreement existed, adding that he ‘could never agree to such a thing.’

Then came, as O’Dwyer expressed it, ‘a whole new ball game.’ On June 29, 1975, at an annual dinner meeting of international museum directors at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio, CAHA officers overheard a loud argument between Louis Casey, then a NASM curator, and Harold S. Miller, an executor of the Wright estate. During the argument, Miller used the word ‘contract’ three times. Casey had mentioned that the wording of the label on the Wright Flyer was to undergo a change. Miller heatedly insisted it could not be changed ‘by contract.’ Miller won.

Learning of the public mention of a contract from CAHA veteran Harvey Lippincott, O’Dwyer renewed his efforts to obtain a copy of the agreement, which he had long suspected might be a key to NASM’s reticence about Whitehead. Letters and visits between O’Dwyer and Senator Lowell Weicker, Jr., of Connecticut, plus senatorial clout and the Freedom of Information Act, were required to extract a copy of the contract from the Smithsonian. The agreement was dated November 23, 1948. One of two signers for the Wright estate was Harold S. Miller and, ‘for the United States of America,’ A. Wetmore, secretary of the Smithsonian Institution.

The clause insisted upon by Orville reads: ‘Neither the Smithsonian Institution nor its successors nor any museum or other agency, bureau or facilities administered by the United States of America, by the Smithsonian Institution or its successors, shall publish or permit to be displayed a statement or label in connection with or in respect of any aircraft model or design of earlier date than the Wright Aeroplane of 1903, claiming in effect that such aircraft was capable of carrying a man under its own power in controlled flight.’ Thus did the Wrights nail down their place in history. Commenting on the contract, O’Dwyer observed recently: ‘The Smithsonian has no authority to represent the people of the United States in any contract if it compromises history. They overstep and abuse their power, especially when they engage in political engineering of this sort.’

Even before the public mention of a contract at the June 1975 dinner meeting, the CAHA was unearthing new facts related to the Whitehead controversy. In a letter to Donald Lopez, assistant director for aeronautics of the NASM, dated January 28, 1974, Harvey Lippincott, president emeritus of the CAHA, stated: ‘I have attached a copy of a letter I have written to Paul Garber regarding our discovery of a new witness to the flights of Gustave Whitehead….Owing to the advanced age (94) of the witness, expediency is urged….The new witness lived next door to Whitehead in 1901–1903, and described a public flight before many neighbors…prior to 1903, from all indications. We urgently request your presence on Saturday, February 2, at 10 a.m., for a recorded interview with this witness.’

Subsequently, a memo by Lippincott dated February 1, noted, ‘Lopez phoned today that he and Garber will be unable to attend the February 2 interview.’

Later, on February 15, Lippincott recorded: ‘On February 2, 1974, at Trumbull, Conn., Mrs. Elizabeth Koteles described a flight of a monoplane by Gustave Whitehead near the baseball diamond at Gypsy Springs, Fairfield. She said the airplane took off from, and landed undamaged, on level ground. The plane was about four feet in the air and flew maybe 100-150 feet….From photos displayed, she picked out Airplane No. 21 of 1901 as the plane she saw. I was much impressed by her effort to recollect, and her sincerity and truthfulness. If she did not know something she said so.’

Whitehead’s claimed flight of August 14, 1901, was described by writer Richard Howell in the August 18 issue of the Bridgeport Sunday Herald as covering a half mile at heights of up to 50 feet. Howell, an artist before he became a reporter, illustrated his article with an accurate drawing of airplane No. 21 in flight above an open field at Fairfield. Howell was erroneously referred to as editor of the Herald in later publicity. Whitehead’s detractors, already debunking Howell’s story as ‘only imagination,’ used that error as further ammunition. Why, they asked, would an editor hold such an important story for four days instead of giving it front page headlines on August 14? Not only did they overlook the fact that the Herald, a weekly, was published only on Sunday, but they also failed to recognize that in 1901 Howell was not the Herald’s editor, but its sports editor. As such, he had placed his article on page one of his sports section.

O’Dwyer, curious about Howell, spent hours in the Bridgeport Library studying virtually everything Howell wrote. ‘Howell was always a very serious writer,’ O’Dwyer said. ‘He always used sketches rather than photographs with his features on inventions. He was highly regarded by his peers on other local newspapers. He used the florid style of the day, but was not one to exaggerate. Howell later became the Herald’s editor.’

Howell’s story in the Sunday Herald said that Whitehead and two helpers (James Dickie and Andrew Cellie), along with the reporter, had traveled through the pre-dawn darkness from Bridgeport to Fairfield on August 14, 1901. Whitehead and Cellie rode in the aircraft, which rolled over the road on four wooden wheels. Dickie and Howell followed on bicycles. At Fairfield, Howell said, the airplane, with 220 pounds of sand ballast aboard, made a brief tethered hop; he then described the manned flight.

‘By the time the light was good,’ Howell wrote, ‘the bags of sand were taken out of the machine….An early morning milkman stopped in the road to see what was going on. His horse nearly ran away when the big white wings flapped [as the engines were started]….The nervous tension was growing and no one showed it more than Whitehead who still whispered at times, but as the light grew stronger he began to speak in his normal tone of voice. He stationed his two assistants behind the machine with instructions to hold onto the ropes and not let the machine get away. Then he took his position in the great bird. He opened the throttle of the ground propeller and [the craft] shot along the green sod at a rapid rate. ‘The two assistants held on as best they could, but the ship shot up into the air like a kite. It was an exciting moment. ‘We can’t hold her,’ shrieked one of the rope men. ‘Let her go then,’ shouted Whitehead back. They let go, and…the machine darted up through the air like a bird released from a cage. Whitehead was greatly excited and his hands flew from one part of the machine to another.

‘The newspaperman and the two assistants stood still for a moment watching the air ship in amazement. Then they rushed down the slightly sloping grade after the air ship. She was flying now about fifty feet above the ground and made a noise like the ‘chung, chung, chung’ of an elevator going down a shaft.

‘Whitehead had grown calmer now and seemed to be enjoying the exhilaration of the novelty. He was headed straight for a clump of chestnut sprouts that grew on a high knoll. He was now about forty feet in the air and would have been high enough to escape the sprouts had they not been on a high ridge. He saw the danger ahead and when within two hundred yards of the sprouts made several attempts to manipulate the machinery so he could steer around [the trees], but the ship kept steadily on her course, head-on for the trees.

‘Here it was that Whitehead showed how to utilize a common sense principle which he noticed the birds make use of when he was studying them in their flight. He simply shifted his weight to one side more than the other. This careened the ship to one side. She turned her nose away from the clump of sprouts when within fifty yards of them and took her course around them as prettily as a yacht on the sea avoids a bar. The ability to control the air ship in this manner appeared to give Whitehead confidence, for he was seen to take time to look at the landscape about him.’

Howell’s account continued: ‘He had soared through the air for fully half a mile and as the field ended a short distance ahead, the aeronaut shut off the power and prepared to alight. He appeared to be a little fearful that the machine would dip ahead or tip back when the power was shut off, but there was no sign of any such move on the part of the big bird. She settled down after the propellers stopped and lighted on the ground on her four wooden wheels so lightly that Whitehead was not jarred in the least.’

In the 1930s, author Stella Randolph questioned James Dickie-named as one of Whitehead’s helpers by Howell-about his part in the claimed flight of August 14, 1901. Dickie denied he had been present and also said that he never knew anybody named Andrew Cellie. The Smithsonian and other Whitehead detractors later used the apparent discrepancy to cast doubts on the credibility of Howell’s Herald article.

‘In 1963,’ O’Dwyer said, ‘when I read of Dickie’s denial, I wondered if he was the same Jim Dickie I’d known ever since I was a youngster. I phoned him, and although he was much older than I, he remembered me well and we kidded each other about the old days. But his mood changed to anger when I asked him about Gustave Whitehead.

‘He flatly refused to talk about Whitehead, and when I asked him why, he said: ‘That SOB never paid me what he owed me. My father had a hauling business and I often hitched up the horses and helped Whitehead take his airplane to where he wanted to go. I will never give Whitehead credit for anything. I did a lot of work for him and he never paid me a dime.’ I noticed, though, that Dickie did not tell me he was not with Whitehead on August 14, 1901, saying simply, ‘I don’t want to talk about it.’ Also, he did not say he never knew anyone named Andrew Cellie-not surprising since Cellie was Dickie’s next-door neighbor on Tunis Hill in Fairfield, and they both hung around Whitehead’s shop.’

O’Dwyer, searching through old Bridgeport city directories in the 1970s, found that Andrew Cellie, a Swiss or German immigrant also known as Zulli and Suelli, had moved to the Pittsburgh area in 1902. Meanwhile, Cellie’s former neighbors in Fairfield assured O’Dwyer that Cellie had ‘always claimed he was present when Whitehead flew in 1901.’

Orville Wright wrote an article for U.S. Air Services magazine in 1945 under the headline, ‘The Mythical Whitehead Flight.’ An excerpt follows: ‘In May, 1901, Stanley Y. Beach visited Whitehead at Bridgeport and wrote an illustrated article about Whitehead’s machine which was published in the Scientific American on June 8, 1901….Although Beach saw Whitehead frequently in the years 1901–1910, Whitehead never told him he had flown. Beach has said that he does not believe that any of Whitehead’s machines ever left the ground under their own power.’

Stanley Yale Beach was the aeronautical editor of Scientific American. A resident of Stratford, he helped finance Whitehead for some time. Beach also designed a Whitehead-built biplane that suffered from a major flaw: its wings were flat, with no curvature, or ‘camber.’ It never flew despite Whitehead’s effort to alleviate Beach’s error by installing a cambered monoplane wing behind the flat surfaces. A few excerpts from Beach’s reports in Scientific American in 1906 and 1908 contradict Orville’s version of Beach’s beliefs about Whitehead.

Beach’s reports referred to powered flights in 1901 by Whitehead in the issues of January 27, November 24 and December 15, 1906, and January 25, 1908. Included were these phrases: ‘Whitehead in 1901 and Wright brothers in 1903 have already flown for short distances with motor-powered aeroplanes,’ ‘Whitehead’s former bat-like machine with which he made a number of flights in 1901,’ ‘A single blurred photograph of a large bird-like machine constructed by Whitehead in 1901 was the only photo of a motor-driven aeroplane in flight.’

The last quote is from a long article by Beach on the first annual exhibit held by the newly formed Aero Club of America at the 69th Regiment Armory in New York City. The report appeared in Scientific American, January 27, 1906. In that issue Beach also wrote, ‘It would seem that aeroplane inventors would show photographs of their machines in flight to at least partially substantiate their claims.’ That barb, according to O’Dwyer, was clearly aimed at the Wrights, who had been invited to show photographic evidence of their December 17, 1903, flight but refused even to attend the exhibit. ‘That famous photo,’ O’Dwyer added, ‘did not surface until 1908.’

Beach’s January 27, 1906, report also noted that’such secrecy [the Wrights’] was in sharp contrast to the ‘free manner’ with which glider pioneer Lilienthal ‘gave the results of his experiments to the world.”

Almost a year later, in his report on the second annual exhibit of the Aero Club of America (Scientific American, December 15, 1906), Beach wrote: ‘The body framework of Gustave Whitehead’s latest bat-like aeroplane was shown mounted on pneumatic tired, ball-bearing wire wheels….Whitehead also exhibited the 2-cylinder steam engine which revolved the road wheels of his former bat machine, with which he made a number of short flights in 1901.’

Why did Beach, an enthusiastic supporter of Whitehead who liberally credited Whitehead’s powered flight successes of 1901, later become a Wright devotee? O’Dwyer offered some intriguing answers, all reflected by his research files, which state that in 1910 Whitehead refused to work any longer on Beach’s flat-winged biplane. Angered, Beach broke with Whitehead and sent a mechanic to Whitehead’s shop in Fairfield to disassemble the plane and take it to Beach’s barn in Stratford. In later years (in O’Dwyer’s words), ‘Beach became a politician, rarely missing an opportunity to mingle with the Wright tide that had turned against Whitehead, notably after Whitehead’s death in 1927.

‘The significance of the foregoing can be appreciated by the fact that Beach’s 1939 statement denouncing Whitehead (almost totally at odds with his earlier writings) was quoted by Orville Wright (as shown earlier). Far more important, however, was the Smithsonian’s use of the Beach statement as a standard and oft-quoted source for answering queries about aviation’s beginnings-because it said that Gustave Whitehead did not fly.’

O’Dwyer also focused his recent reflections on the missing photograph of Whitehead’s Airplane No. 21 in apparent flight in 1901-the blurred picture referred to by Stanley Beach in Scientific American, January 27, 1906.

William J. Hammer, Thomas A. Edison’s chief electrical engineer, was also a renowned aeronautical photographer and a founding member of the Aero Club of America. ‘Hammer,’ O’Dwyer said, ‘reserved an entire wall to show some of his own photographs from a collection (cited by Alexander Graham Bell as ‘the largest collection of aeronautical photos in the world’). It was Hammer’s exclusive wall, with one exception: six Whitehead photos, including four static views of Whitehead’s 1901 monoplane, one of his 1903 engines and the all-important sixth picture-the ‘blurred photograph of a large bird-like machine constructed by Whitehead in 1901…of a motor-driven aeroplane in flight,’ as described by Beach in Scientific American.’

‘After a long and fruitless search,’ O’Dwyer continued, ‘one of our members stumbled on a book, Dreams of Wings, in which were reproduced the missing photos as they had appeared on the 1906 exhibit wall. The photo, by the exhibit cameraman, was shot from at least 40 feet away and at an angle to include a large part of the wall. The blurred picture was visible tucked partly under the top right corner of a frame surrounding the four static views of Airplane No. 21. Ironically, the book’s author was Thomas B. Crouch, then the Smithsonian’s curator of early aircraft [who later directed the aeronautical department], and the photos were credited to the Smithsonian.’

O’Dwyer admits that it is impossible to identify the blurred object as an aircraft from a long-range shot of the wall-despite the research committee’s use of blow-up and modern computer studies of the picture. But, he emphasized, Stanley Beach saw the picture close up, examined it and fully described what was discernible-Whitehead in successful motor-driven flight.

The investigating committee’s more recent research has established for the first time the location of the claimed flight of August 14, 1901. The route taken by Whitehead and his helpers to reach the flight site from Bridgeport (as described in Howell’s Herald story on August 18), the testimony of at least two witnesses and the illustration drawn by Howell all combine to place the site at Turney’s Farm, about a half mile north of the Long Island Sound.

‘From all indications,’ said O’Dwyer, ‘Whitehead made his takeoff run diagonally across the farm, corner to corner, heading southwest into the prevailing wind. This gave him a potential flight course of at least a mile before reaching Fairfield Beach. Howell’s drawing depicts Whitehead aloft in Airplane No. 21, a line of elms and chestnut trees atop a knoll in the distance, and two stone walls intersecting near the trees. Today, the walls are still there, easily found and identifiable as those that Howell sketched almost a century ago!’

Members of the CAHA and the 9315th Squadron went door-to-door in Bridgeport, Fairfield, Stratford, and Milford to track down Whitehead’s long-ago neighbors and helpers. They also traced some who had moved to other parts of Connecticut and the United States. Of an estimated 30 persons interviewed for affidavits or on tape, 20 said they had seen flights, eight indicated they had heard of the flights, and two felt that Whitehead did not fly.

‘Look, I never knew Whitehead personally or anything about his aircraft. All I did was watch him fly.’ So spoke Frank Lanye, 92, on June 15, 1968, at his home in Waterbury, Conn. He was describing an autumn flight near Fairfield Beach in 1901, a year he remembered because it was a year after his 1900 discharge from the Navy. Present at the taped interview were the Smithsonian’s Garber, the CAHA’s Lippincott, O’Dwyer, and Don Richardson, the latter a Sikorsky Aircraft engineer.

John Ciglar, a Pine Street neighbor of Whitehead in 1901, told a Bridgeport Sunday Post reporter in 1940: ‘I was nine years old when I and a group of other boys saw Whitehead fly in July or August 1901. I vividly recall the flight in a vacant lot at the corner of Cherry Street and Hancock Avenue in the West End of Bridgeport….Whitehead put every nickel he earned into flying machines, but as far as patents and recognition were concerned he didn’t seem to care.’

Ironically, several flight experimenters who later dismissed Whitehead as a fraud showed a strange curiosity about his work. Testimony exists, for example, that the Wright brothers visited Whitehead’s Bridgeport shop in 1901 and 1902 and had discussions with him. Among the witnesses were Anton Pruckner, Whitehead’s young machinist and engine assistant, and Cecil Steeves, another of Whitehead’s young neighbor helpers. Asked in later years how he knew the two men were the Wright brothers, Pruckner replied, ‘They had to introduce themselves.’ He said the pair visited ‘more than one time.’ Steeves, in a recorded interview in 1937, said he remembered a visit by the Wrights. ‘They came from Ohio,’ he said, ‘and under the guise of offering to help finance Whitehead’s inventions, actually received inside information about his work…. After they had gone away, Mr. Whitehead turned to me and said, ‘Now that I have given them the secrets of my invention they will probably never do anything in the way of financing me’-a good prophesy, as it turned out.’

Charles M. Manley, a mechanic for Samuel P. Langley, opted for amateur espionage rather than a shop visit. In late 1901, Whitehead was exhibiting his Airplane No. 21 in Atlantic City, and Manley assigned a clerk to visit the display and obtain technical data. The engine date he wanted included explosions per minute in the cylinders, method of cooling cylinders, propeller rpm at full power, and method of transmitting power to propellers via bevel gears. Regarding the airframe, Manley wanted to know how the brace rods were joined to the body of the craft, plus the wing, tail and propeller dimensions.

In a 1940 interview with reporter Michael D’Andrea of the Bridgeport Sunday Post, Louise Whitehead said her husband was always busy with motors and planes when he wasn’t working in coal yards or factories to earn money for his aeronautical efforts. ‘I hated to see him put so much time and money into that work,’ she said.

Mrs. Whitehead said her husband’s first words upon returning home from Fairfield on August 14, 1901, were an excited, ‘Mama, we went up!’ Mrs. Whitehead, however, said she never saw any of her husband’s flights.

Whitehead’s efforts to solve the problems of flight took their toll on the family budget. Louise Whitehead had to work to help meet expenses. But the couple was able to buy land on Tunis Hill, where, with the help of their son Charles, Whitehead built two homes, in 1903 and in 1912. The two houses still stand. He also planted a large orchard from which he sold fruit, and kept a cow and chickens to help with the family’s food supply.

Junius Harworth, who, with Anton Pruckner, was one of Whitehead’s more important helpers, said in later years that Whitehead could have made a good living building engines alone. Rose Whitehead Rennison, the eldest of the couple’s three daughters, recalled that her father received so many orders and advance payments for engines that he simply returned them. ‘He was more interested in airplanes,’ she said, ‘and sold only enough engines to provide more money to further his efforts to fly.’

Whitehead lost an eye when struck by a chip of steel in a Bridgeport factory. He also suffered a severe blow to the chest when hit by a piece of factory equipment, an injury believed to have contributed to his increasing attacks of angina. These setbacks brought slowdowns in his activities, although he exhibited an aircraft at Hempstead, N.Y., as late as 1915. Whitehead continued to work and invent. He designed a braking safety device, trying for a prize offered by a railroad. He demonstrated it as a scale model but failed to win the award. He constructed an ‘automatic’ concrete-laying machine, which he used to help build a road in Long Hill, just north of Bridgeport. He profited no more from those inventions than he did from his airplanes and engines.

On October 10, 1927, in his 54th year, Gustave Whitehead died of a heart attack, leaving his family with their home and $8. His grave in Lakeview Cemetery, Bridgeport, was marked only by a bronze spike bearing the cemetery number 42. His pioneering work has been largely denied or forgotten for 37 years.

Thanks to members of the CAHA and the 9315th Reserve Squadron, a headstone replaced spike 42 at commemorative graveside ceremonies on August 15, 1964. The granite stone bore a likeness of Airplane No. 21 and the inscription, ‘Gustave Whitehead, January 1, 1874–October 10, 1927. Father of Connecticut Aviation.’ Present were aviation pioneers Charles Wittemann and Clarence Chamberlin. Whitehead’s then surviving daughters-Rose Rennison, Lilian Baker and Nellie Kusterer-were present, as were Anton Pruckner and representatives of all U.S. Armed Forces, the CAHA, the 9315th Squadron, and state and local governments. A statement from Connecticut Governor John Dempsey proclaimed August 15 as ‘Gustave Whitehead Day,’ as did statements from Bridgeport and Fairfield officials.

Meanwhile, the long-suffering ghost of Gustave Whitehead still stands in the wings awaiting its summons on stage.

This article was originally published in the March 1996 issue of Aviation History and written by Frank Delear, a native of Boston and a retired public relations director of Sikorsky Aircraft, Stratford, Conn. He is the author of five books and many newspaper and magazine articles, including a feature on Harriet Quimby that appeared in Aviation History, January 1991. For further reading: History by Contract, by William J. O’Dwyer; and Before The Wrights Flew, by Stella Randolph.

For more great articles subscribe to Aviation History magazine today!