‘This classic gun duel high in the Sierra Madre of Chihuahua, Mexico, would be the bloodiest exploit of Paul’s long career as a lawman’

Bob Paul spurred his jaded horse toward the sprawling adobe hacienda, its front patio shaded by a ramada of brush and tree branches. Behind him rode a fellow railroad detective and six Mexican cavalrymen. Inside the adobe three ragged American desperadoes tensed, fingers gripping their six-shooters. They were members of the Larry Sheehan band, which had robbed a train at Stein’s Pass in New Mexico Territory the previous month. The long manhunt, which had taken the famous lawman deep into Mexico, was about to explode in gunfire in mid-March 1888. This classic gun duel high in the Sierra Madre of Chihuahua would be the bloodiest exploit of Paul’s long career as a lawman.

Although he rates as one of the great peace officers of the Old West, Paul is remembered today principally for his friendship with Wyatt Earp and the stirring events both before and after the October 26, 1881, gunfight near the O.K. Corral in Tombstone, Arizona Territory. But Paul had been a veteran lawman in Gold Rush California while the Earp brothers were still wearing knee pants. For nearly 50 years he enforced the law without fear or favor on two of the wildest frontiers of the Old West. From his disbanding of the notorious Tom Bell gang in the California goldfields in 1856 to his desperate gun duel with the Sheehan band of train robbers in Chihuahua in 1888, Paul played a prominent role in some of the frontier’s most dramatic events.

Paul battled lynch mobs and tracked down horse thieves, cattle rustlers, murderers and stage robbers. He fought in several memorable gun battles of the Southwest, sending five dangerous outlaws to their graves. His shootout with the notorious Cowboys while riding shotgun on the Tombstone stage sparked Arizona Territory’s infamous Earp-Clanton feud and its resulting showdown in a vacant lot adjacent to the O.K. Corral. His bloody gun duels with the Rancheria killers of the California Gold Rush and the Red Jack gang in Arizona Territory almost 20 years later were as exciting as anything filmmakers could conjure. More compelling still—filmmakers, please take note—was his well-planned pursuit of the Sheehan gang, capped by the gripping gunfight of the Sierra Madre.

Robert Havlin Paul’s life of high adventure began in Massachusetts on June 12, 1830, and at age 12 he went to sea on a whaler. He sailed the South Pacific and landed in California soon after gold was discovered, serving as a constable, deputy sheriff and sheriff of wild and woolly Calaveras County in the 1850s and ’60s. Later he served Wells Fargo as a shotgun messenger and detective. Wells Fargo sent him to Arizona Territory in 1878, and he quickly became the most experienced lawman in the territory. His powerful stature—6-foot-4, 240 pounds—coupled with his ability and popularity won him the office of sheriff of Pima County, a post he held from 1881 to 1886. During those years he became the best-known sheriff in the Southwest.

A year after Paul left office, outlaws pulled off two daring train robberies east of Tucson. Authorities quickly arrested Larry Sheehan and Dick Johnson, a pair of loudmouthed, deadly cattle rustlers, but soon released them for lack of evidence. As the two left the Pima County Courthouse, Sheehan remarked sarcastically to Tucson lawmen, “We have never robbed any trains yet, but as long as we have been accused, we are going to get busy and rob one for luck.”

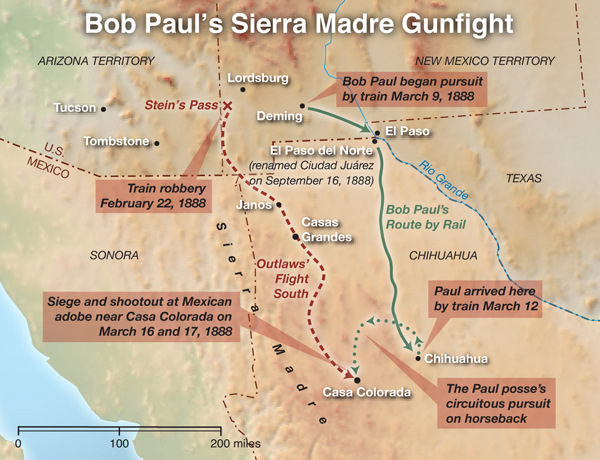

He wasn’t fooling. With saddle partner Dick Hart they rode 225 miles south from El Paso, Texas, to Chihuahua, Mexico, looking for a ranch to buy. Then they started back to the United States to raise a stake. On the way north through the Sierra Madre (a horseshoe of three mountain ranges that encloses the great central Mexican Plateau), Sheehan accidentally shot himself in the leg, so Johnson and Hart continued on without him. On the night of February 22, 1888, Johnson and Hart boarded a Southern Pacific train at Stein’s Pass, New Mexico Territory, near the Arizona Territory line. The bandits ordered the engineer to stop at a place they thought was in Arizona, just beyond the New Mexico line. A year earlier New Mexico’s territorial government had enacted a law making train robbery a capital offense; for that reason Johnson and Hart wanted to stop the train on the Arizona side. But in the darkness they had stopped the train early and were actually still in New Mexico. The robbers took $2,000 plus a shipment of jewelry and fled back into Mexico.

A hastily organized, ill-equipped posse led by Arizona Territory U.S. Marshal William K. Meade started in pursuit. Meade, a bitter personal and political enemy of Paul, was eager to collect the generous reward. But in his haste he had neglected to obtain permission to cross the border, and Mexican authorities in Janos jailed Meade and his men. For more than a week no one in Arizona knew the posse’s whereabouts; the public simply assumed the men were on the bandits’ trail, deep in Mexico. Finally on March 9 an American arrived in Lordsburg from Janos and reported the posse’s arrest. The story hit the wires immediately, making national news and creating a diplomatic incident.

Meanwhile Paul had been conducting his own investigation for the Southern Pacific into the Stein’s Pass train robbery. He later explained that the day after the holdup, “General Superintendent J.A. Fillmore telegraphed from San Francisco to [Scott] Noble to send me after the train robbers.” Paul immediately boarded a train for Stein’s, arriving late the same day, after Meade’s posse had left for Mexico. Then, after dutifully obtaining permission to enter Mexico, Paul spent a week south of the border trying to intercept the robbers. He returned to the United States on March 6 and went to Deming, New Mexico Territory, a railroad town, perhaps hoping to pick up leads on the fugitives. There Paul learned that the Southern Pacific had appointed him detective for Arizona and New Mexico territories.

Paul was still in Deming on March 9 when news of Meade’s arrest came over the telegraph wires. The old manhunter didn’t waste a moment. He boarded the next train for El Paso, where he met with J.E. Lindberg, superintendent of the Galveston, Harrisburg & San Antonio Railroad. Crossing the border to El Paso del Norte (present-day Ciudad Juárez), Paul and Lindberg met with the American consul and asked him to make every effort to have Meade and his posse released. Hearing that Chihuahua Governor Lauro Carrillo happened to be in town, Paul called on him. “I went to the governor,” he explained, “and he was very nice and very courteous. He told me I might have all the horses and men needed to pursue the robbers, and I went back to my hotel to fix my plans.”

Carrillo instructed Paul to meet with Acting Governor Juan Zabrian in the capital city, so the lawman boarded the Mexican Central Railway for Chihuahua, 230 miles to the south. Arriving on the morning of March 12, he immediately sought an audience with Zabrian. Paul recalled that Zabrian “was quite sharp and short with me” and had declared: “You Americans come down here and want everything. How do I know that you are what you say you are?”

The veteran lawman was stunned when the Mexican bureaucrat refused to help. Zabrian complained that American detectives had “imposed upon” him during a recent train robbery investigation south of the border. Undaunted, Paul first consulted with Nicholas F. Pierce, detective for the American-controlled Mexican Central Railway, then sent a telegram to Governor Carrillo, asking him to overrule Zabrian. Carrillo replied the next day, ordering Zabrian to cooperate with the American detectives. Said Paul of the chastened official: “He sent for me and was very nice. He offered me all the men and horses I wanted.” Zabrian assigned an orderly sergeant, a second sergeant and four privates to assist in the manhunt, putting them under Paul’s direct supervision. They were provided with good horses and provisions, and on the morning of March 14 Paul, Pierce and the six soldiers rode out of Chihuahua.

Paul’s 30 years of manhunting experience was soon abundantly evident. He suspected the outlaws might turn up in the Sierra Madre west of Chihuahua, as that was the route they had taken on their ride north. Paul decided to follow their old trail north, anticipating they would return south by the same route. He astutely recognized that the Sheehan bunch were strangers to Mexico and would probably follow the trail they knew best. Paul and his posse rode 21 miles north to Rancho El Fortín, where they camped for the night. Here the soldiers made inquires and found that Sheehan, Hart and Johnson had indeed passed through a month earlier on their northward ride. This was a hopeful sign, and in the morning they pressed on, riding all day and 57 miles in a circuitous route to Carretas. The next day, March 16, the trail took them south 58 miles to Casa Colorada, high in the Sierra Madre and just west of present-day Cuauhtémoc. A mile and a half shy of Casa Colorada they passed a large L-shaped adobe with a big stone corral. Unknown to Paul, Larry Sheehan, Dick Hart and Dick Johnson were inside, lodging for the night with a Mexican family. Just as Paul suspected, they had backtracked toward Chihuahua. The outlaws watched Paul’s posse ride by, but they suspected nothing.

At Casa Colorada the soldiers made their usual inquiries and were gratified to learn that three heavily armed gringos, matching the fugitives’ descriptions, were still at the big adobe. The Americans were bearded and ragged from their long flight southward. Night was falling, and Paul decided not to wait until daylight but to try to capture them immediately. He recruited six volunteers from Casa Colorada and started for the big adobe. En route three of the locals got cold feet and disappeared, but Paul and Pierce, with the six soldiers and three remaining volunteers, quietly took up positions in the brush a short ride from the house. It was a typical thatched-roof Mexican adobe with four large rooms that housed an extended family of about two dozen men, women and children. As the family grew, its men had added on the windowless adobe rooms. There were no doorways between each room; rather, the front door of each opened onto an outdoor patio in the L-shaped angle formed by the structures. A ramada of brush and tree branches provided shade.

One of the Mexican volunteers lived in the adobe, and Paul told him to scout the house. He soon returned and told Paul the robbers were eating dinner in the kitchen, at the right, or north, end of the adobe. He also said the fugitives had left their rifles in the bedroom at the opposite end. Paul asked if the volunteer would try to get their rifles, and the man agreed. He silently entered the room, found two Winchesters, ducked back out and brought them to Paul. Then the man returned to find the third rifle. After some searching, he found it resting on a shelf. But as he picked it up, Sheehan, Johnson and Hart, having finished their supper, suddenly stepped inside. The trio angrily demanded to know what he was doing with the rifle. The startled man made an excuse and quickly set down the weapon, but the outlaws suspected trouble and refused to let him leave.

After a long delay Paul suspected the volunteer might have met with foul play. He and his posse mounted up and rode quickly to the adobe, positioning themselves across from the angled patio to guard its four doors. The outlaws slammed shut the door to their room and frantically searched for their Winchesters. They demanded the Mexican man turn over their rifles, but he denied any knowledge of them. Paul, Pierce and the troops remained on horseback, facing the patio. Then Paul and Pierce dismounted and yelled for the outlaws to surrender. There was no reply. The Mexican second sergeant grew impatient. Leaping from his horse, he ordered one of his men to follow him as he charged the door of the room. As he smashed it open with the butt of his rifle, the outlaws unleashed a volley of fire. The sergeant dropped dead with a bullet in his heart. “It was a foolish thing to do,” Paul recalled. “There must have been 20 shots gone over our heads, and some of them through the soldier. That ended him.”

From the doorway the three bandits sent a blistering fire with their six-shooters, and the soldier who had followed the sergeant fled in a hail of lead. In the kitchen and adjacent room, which formed the right angle of the adobe, the 21 resident women and children began screaming hysterically. Some ran outside and then back into the center room, beside the kitchen. Paul had the soldiers order the residents to flee the adobe. Several tried, but the outlaws fired at them from the doorway, and they rushed back inside. Paul yelled at his men to hold their fire so as not to endanger the innocents. The outlaws then dragged the sergeant’s body inside, barred the door and settled in for a siege.

Bob Paul recognized an impending disaster and decided to seek help. He sent one of the Mexican volunteers on horseback to the nearest town, Cusihuiriachi, 15 miles to the south. Cusihuiriachi, now virtually deserted, was then a prosperous silver mining town of 3,000 and large enough to have an alcalde, a combination mayor and judge. Later that night the alcalde arrived with a half-dozen armed reinforcements. Paul now had a force large enough to surround the adobe and stone corral. After stationing men at 10-foot intervals, he and Pierce took up positions atop the structure to prevent the bandits from escaping through the roof.

In the meantime the alcalde ordered several of his men to dig a hole through the back wall of the kitchen, the room farthest from that held by the bandits. The women and children within, half crazed from fright, scrambled through the hole to safety. The rescuers then entered and began carving another hole through to the adjacent room to free the remaining women and children. The outlaws, hearing the digging, ordered their Mexican hostage to help them carve a hole in the bedroom wall. From there they crawled into the first middle room and dug another hole through the opposite wall. Sheehan and Hart scrambled through it into the kitchen just in time to see the last of their hostages escaping though the hole in the back wall. They opened fire at close range at the fleeing women and children. Their muzzle flashes set one girl’s dress on fire. “One discharge grazed across the back of that girl,” Paul recalled, “and of all the screaming and yelling you ever heard, she did it.” She ran toward her rescuers, who seized her and smothered the flames. “She was not much hurt,” said Paul.

The standoff continued, and the posse maintained its watch all night. Every 10 minutes Paul would call out, “Are you awake?” Each time he received the same answer down the line of sentries: “Despierto, señor” (“I am awake, sir”).

At first light on March 17 Paul again demanded the outlaws surrender. They refused, shouting they would never be taken alive. Johnson was in the bedroom at far left, giving him command of the patio. Sheehan and Hart remained in the kitchen at the opposite end, one watching the patio while the other guarded the hole in the back wall. Paul decided to blast them out and instructed one of the Mexican volunteers to ride to Cusihuiriachi and get a supply of giant powder from the mines. By late morning the man had not returned, so Paul climbed onto the kitchen roof to explore other options. He found that beneath the adobe bricks was a patchwork of brush supported by wooden beams. Scraping away the adobe, he set a match to the brush patchwork. After several attempts he managed to get a fire started and jumped down from the roof. The flames quickly spread, smoke poured out the doors and the fire began to roar like a furnace. Sheehan and Hart struggled to douse the flames. Finally, almost overcome by the smoke and heat, they drew their pistols for a last stand. In a scene out of a Hollywood film they burst out the door, six-shooters belching lead.

“They came out calling us sons of bitches and shooting, a gun in each hand,” recalled Paul. “We let them have it in return.” Paul and the men flanking the patio opened up with a terrific volley of rifle and pistol fire. Dick Hart reeled, sieved by bullets that killed him instantly. Larry Sheehan, desperately wounded, staggered back into the room, collapsed upright on an adobe bench and died. Soon the inferno spread to the opposite bedroom. When Dick Johnson could stand the smoke and heat no longer, he too charged headlong at the posse, clutching a six-gun in each fist and firing as fast as he could thumb the hammers. He made it 10 feet before the guns of Paul and his posse knocked him face down. Johnson struggled once more to his knees, fired both pistols, then fell forward dead, riddled with bullets.

Paul stepped forward and searched Johnson’s body. In the outlaw’s pockets he found $595 in cash, a pair of diamond earrings and 21 opals, all stolen in the train robbery. He then turned to Hart’s body and searched it. “[I] found poor picking,” Paul later admitted. “The soldiers had got there first.” Paul thought it “just as well to say nothing about it, as the loot obtained by the troops would encourage them to give willing and efficient aid [in future].” When the fire died down, Paul had Sheehan’s body brought outside. The flames had severely burned the gang leader’s body, singeing off his hair and beard and disfiguring his face.

Paul and railroad detective Pierce accompanied the alcalde to Cusihuiriachi, from which Paul sent a wire to the Southern Pacific superintendent: “Our posse found the Stein’s Pass robbers, Sheehan, Hart and Johnson, about 120 miles west of Chihuahua on the night of the 16th. We called on them to surrender, and they took refuge in an adobe house, where they were attacked by us. They killed one man; [we] burnt them out after 18 hours fight. All three men were killed fighting. The bodies were brought here, and we recovered about $600 and jewelry. Cannot say when I can leave here. The inquest will be held today. Will advise you later. R.H. Paul.”

Mexican authorities buried the dead sergeant in Cusihuiriachi with military honors. Paul had a local photographer take postmortem images of the three outlaws before having them unceremoniously buried in the local cemetery. Armed with these photographs as proof of his successful manhunt, Paul made the long trip back to the United States, arriving home in Tucson on March 23. By that time newspapers nationwide had published accounts of his manhunt. The San Francisco Examiner then issued a lengthy report based on information from Deputy U.S. Marshal H.J. Burns, a friend of Paul’s from that city who had gone to Arizona Territory to participate in the manhunt. The Examiner’s account, picked up by wire services and reprinted nationwide, bore the graphic headline ROBBERS ROASTED OUT: HOW SHERIFF PAUL COOKED THE THREE OUTLAWS OF STEIN’S PASS. It pilloried Meade and praised Paul: “While the U.S. marshal of Arizona and his deputies were getting themselves locked up in a Sonora jail for crossing the frontier without permission, [former] Sheriff Paul took the precaution of applying to the governor of Chihuahua for extradition papers and permission to hunt the robbers on Mexican territory.” The Examiner gave Paul full credit for tracking down the bandits and organizing the siege.

Paul’s success was the culmination of three decades of law enforcement experience. He used every skill he had acquired in his long career: his ability to speak Spanish and his good relations with the Mexican government, coupled with his ability to track like an Indian, outthink his quarry, organize his men, and outshoot and defeat a desperate foe. Paul’s trek into Chihuahua cemented his reputation as one of the greatest manhunters on the Western frontier. For William K. Meade, his ill-fated expedition was among the most humiliating events of his life. He had been bested by a bitter enemy.

In the end Sheehan, Johnson and Hart believed they had no choice but to fight to the death. Had they surrendered and returned to New Mexico Territory, they would have faced the death penalty for train robbery. And once they had killed the Mexican sergeant, they surely would have faced a firing squad in Chihuahua. Still, the editor of Tucson’s Arizona Daily Citizen could not help but admire the outlaws’ courage, and he provided their only epitaph: “However bad their calling or desperate their cause, they died like brave men, with their boots on—a manner that befitted their lives.”

In 1890 President Benjamin Harrison appointed Bob Paul U.S. marshal of Arizona Territory. It was the pinnacle of his law enforcement career. Paul held the post for three years, but when Grover Cleveland was elected president, Meade tasted some revenge with his reappointment to the marshal’s post. Paul spent the next few years mining, then in 1899 became undersheriff of Pima County, serving until January 1901. The lawman had always been robust and healthy, but a few weeks after leaving that post, Paul suddenly took ill. On March 26, 1901, he died in his humble Tucson adobe in the company of his wife, children, grandchildren and friends. He was 70, and no pioneer had lived a life more adventurous.

Today Bob Paul is largely forgotten, his memory as eroded as the crumbling walls of Tucson’s ancient adobes and the played-out placers of old Calaveras. He left behind no memoir, no diary, no dime-novel biography. There is no monument to Paul in Arizona or California, and even his grave is long lost. Yet his story cannot be erased, for his daring deeds etched it indelibly into the history of the American West.

California author John Boessenecker, a frequent contributor to Wild West, has written many well-received Western books. This article was adapted from When Law Was in the Holster: The Frontier Life of Bob Paul (University of Oklahoma Press, 2012).