A pre-invasion recon mission at Iwo Jima exploded into a vicious firefight

[dropcap]F[/dropcap]EBRUARY 17, 1945, HAD DAWNED CLEAR AND BRIGHT OFF IWO JIMA. At 10:45 that morning, Lieutenant (junior grade) Rufus G. Herring, aboard LCI(G)-449, peered through binoculars at the tiny island, still some distance away. Iwo’s rocky coastline, deep gorges, and high ridges no doubt bristled with Japanese machine guns and rocket launchers, with masses of soldiers dug in at field pieces. The Marines had their work cut out for them. But before they could get to work, Herring’s flotilla of gunboats had a job to do.

Herring worried most about Suribachi. The dark gray mountain towered 550 feet, heavy artillery and menace engineered into the natural fortress of a long-dormant volcano on Iwo’s southern tip. He found the sight of it breathtaking, like one of famous Japanese artist Hiroshige’s woodblock prints. He knew that from the crest the Japanese had just as detailed a view of his force, and, beyond the gunboats, the waiting fleet of American battleships, destroyers, and cruisers. Only a line of U.S. Navy destroyers was nearer the shore.

Herring’s little command was Flotilla Three, Group Eight—12 skinny vessels proceeding slowly in the direction of Suribachi, near enough the shore to be in deep trouble if enemy gunners were to open fire.

But there could be no turning back. Flotilla Three had a critical mission, supporting U.S. Navy commandos on reconnaissance. In two days, the fleet behind them would assault Iwo Jima. Right now Herring and his ships—Landing Craft Infantry repurposed into gunboats—were to hug the target’s shore and provide cover for Underwater Demolition Teams of special operations frogmen assigned to disable enemy mines, then scout beaches adjoining Suribachi to make sure tanks and other heavy equipment could traverse the sandy, black volcanic cinders.

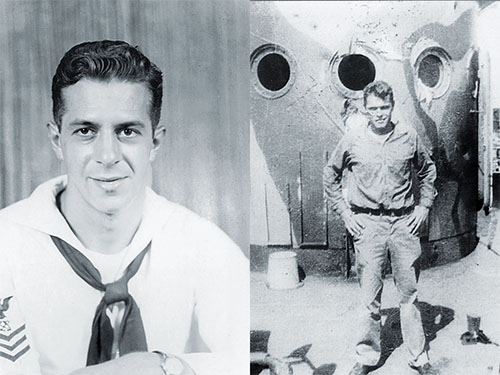

So far everything seemed fine, but Herring and crew were uneasy; surely somebody ashore had spotted them. Herring had fought in the brutal campaigns to take the Marshall and Mariana islands; this was his first combat mission as captain. He knew to take nothing for granted and, when under fire, to lead by example. Stay calm, he told himself. His men had assumed battle stations, crouching at their guns, some strapped right to their weapons, eyes on Suribachi. Herring was thinking maybe they would get in and out without casualties when he felt shaking underfoot. Something shivered. Metal moaned. Water sprayed Herring in the face, and fear came blasting out of nowhere.

IWO JIMA WAS A BARREN NUB OF VOLCANIC ROCK—and, thanks to its location, an unavoidable stop on the bloody slog to Japan. The island, with two airfields from which Japanese fighter pilots sallied against American bombers, sits 670 miles south of Tokyo. In early 1945, that made Iwo a perfect landing zone for B-29 long-range bomber aircrews in trouble—that is, if the Allies could capture it, which they meant to do, starting in two days.

For Herring, the grim little island was another chance for LCI gunboats to prove their mettle. His boat and its companion vessels might lack the cachet enjoyed by battleships and aircraft carriers and destroyers and PT boats, but gunboats were critical to island hopping, and island hopping was critical to victory in the Pacific.

The 449 and cohort had started out configured as Landing Craft Infantry (Large). These 158-foot ships, powered by eight diesel engines, were outfitted to carry 200 troops at sea and deliver those passengers to landing beaches via ramps at either side or through bow doors. Narrow and flat-bottomed, LCIs were bouncy and tended to roll.

Besides having four well decks in which to stow troops, LCIs had four or five 20mm automatic cannons in shielded tubs arrayed around the vessel’s bridge and at its bow. As the island war progressed, the navy saw a need for shallow-draft, heavily armed craft to protect troops landing on beaches and to hunt infiltrating enemy barges. The LCI fit the bill; all it needed was more firepower. In late 1943, the navy began customizing dozens of LCIs by adding 20mm cannons and 40mm Bofors guns, as well as launchers for 4.5-inch rockets. In combat, the rocket pods rode on outboard ramps along the vessel’s side that landing troops once used. The 449 could field 60 rockets on each side, each projectile with a payload of 6.5 pounds of high explosive.

Stairs and ladders connected the vessel’s three levels. The lowest was the first platform, home to the crew’s quarters and engine room. Above was the main deck, from which protruded a deckhouse, containing the wardroom, galley, and radio shack and an infirmary. The highest level was the gun deck, with two single 40mms forward of a 10-foot conning tower and two 20mms aft. In the conning tower was the pilothouse, from which crewmen steered the ship. Atop the conning tower was the bridge, where officers stood during battles, communicating with the crew by a telephone intercom. That December, LCI(G)-449, now studded with weapons, sailed into some of the most dangerous places in the Pacific with Herring as a junior officer.

In September 1944, the 449’s captain got a promotion. Herring, 23, took command. Through the autumn, the 449 made milk runs, shuttling mail and sailors between Saipan and Tinian. Crewmen alternated between swimming and souvenir hunting on Saipan, and scraping and repainting the ship—a quiet interlude that ended in early 1945 with orders that directed the gunboat toward Iwo Jima.

COMING PARALLEL TO THE ISLAND’S EASTERN beaches at 10:20 a.m. the gunboats turned 90 degrees to port, aiming their bows at the shore. All they had to do was advance 3,500 yards past those destroyers, and they would run straight into the beach below Suribachi. Up and down the line, fast boats carrying the navy frogmen idled 100 yards behind the gunboats waiting for the signal to advance to their assigned beaches.

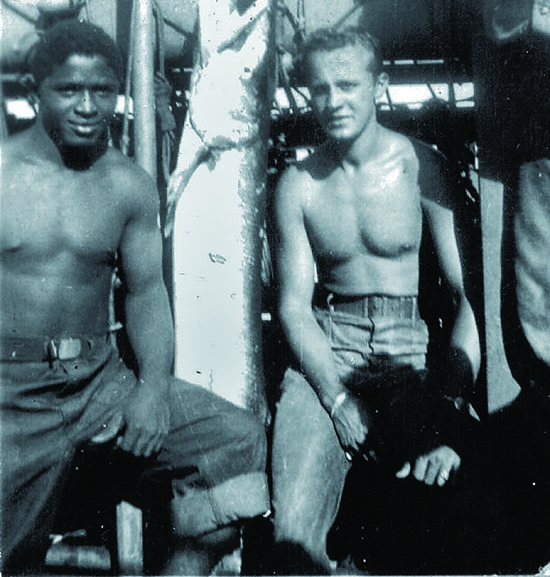

As the 449 closed on the shore, crewmen were going over the battle drill, whose first order was to look out for each other. “When you’re fighting side by side, you’re just as close as you can get,” recalled Charles Hightower, of Russellville, Arkansas, at the time 18 years old. “You’d just die for them.”

Down in the well deck, Steward’s Mate Ralphal Johnson, 449’s only African American, was checking his 20mm before loading it. Oerlikon gunners had to be strapped to their guns. He asked his best friend, Junior Hollowell, 18, of Tulsa, Oklahoma, to harness him. On the ship’s fantail, Pharmacist’s Mate Henry Beuckman and Ensign Leo Bedell were taking the stand-by brigade—a dozen men assigned to deal with problems as they arose—through last-minute instructions should the ship come under fire.

The gunboats jolted through the line of destroyers toward the beach. The demolition teams’ boats zipped along either side of the 449, quickly passing the slower vessel. In the gunboat’s bow, Gunner’s Mate Third Class Chuck Banko could see nothing between him and Iwo except water. Feeling the wind in his face, he watched the shore get closer: 1,900 yards, 1,800 yards, 1,700 yards.

Banko heard what sounded like a car crash. Over to port water geysered, soaking him and spraying the deck. Wiping his eyes, Banko spun left, toward the racket. An enemy round had hit a nearby gunboat, 441, whose hull was belching smoke. The stink of cordite made his nose prickle. That had to be Japanese artillery. Banko scrambled back to his 40mm, shouting to the rest of the gun’s crew, “Get ready!”

“Open fire!” Herring ordered.

The LCI gun crews came alive, throwing metal at the shore as shells of every size rained onto them and exploded. A shell blew up on the 449’s bow, followed by a wall of flame—a mortar round had connected near the 40mm ammunition locker. It was 10:55.

On the bridge, Herring felt a blast of heat. A shock wave nearly knocked him to the deck. He tried to assess the damage at the bow but thick black smoke obscured his view.

AT THE STARBOARD 20MM, HOLLOWELL CAME TO face down. The last thing he remembered was reloading as Johnson fired nonstop. Feeling like he had been punched in the gut, Hollowell stood, stunned. Bodies were strewn like dolls around the well deck. He heard Johnson’s voice from down on the deck. A shell had blown Johnson out of his harness, slashing his right cheek, exposing tissue and shattered teeth. The gunner’s right arm was open to the bone. Hollowell could see tendons. He knelt by Johnson. “You’re going to be okay,” he said. “I promise.”

“I’m dying, Junior,” Johnson said. With each word, he spewed blood onto Hollowell’s face and life jacket. Hollowell ran for the deckhouse. He had to find Beuckman, the medic.

AS LEO BEDELL STEPPED through the door of the deckhouse onto the well deck, a coppery odor of blood and death hit him. Bodies sprawled under roiling smoke. He wondered where to start.

“Leo, get the fire under control,” Beuckman said. “I’ll start taking care of the wounded.”

Bedell nodded. The standby brigade had followed him. He told them to grab the fire hoses off the bulkheads and attack the fires in the bow. As the sailors fanned out, the soles of their shoes bogged down in bloody muck that made a horrible sucking sound.

The Japanese artillery was fast, furious, and beautifully camouflaged. The radio traffic said other gunboats were taking hits. The 449 pressed ahead, now less than a thousand yards from the beach—well within reach of the big guns emplaced on shore.

Beuckman was about to splint Johnson’s arm when a blast overhead slammed the medic to the deck: another mortar round, this time between the two 40mms below the bridge.

It was 10:57.

Two hits in two minutes. The bow and the gun deck were burning. Everywhere men scrambled they came upon bodies, twitching in pain and moaning or silent and motionless.

ON THE WELL DECK, Beckman got to his feet. Both hits had been bad. He ordered Hollowell to start bringing wounded to the mess deck, then climbed a ladder to the gun deck, afraid of what he would find.

It was worse than that. All around him, dying men were screaming. All he could do was keep going and hope he had enough bandages, sulfa, and morphine.

FROM THE BRIDGE RUFUS HERRING could see casualties scattered on the decks. Men were rushing about, risking their lives to carry other sailors to safety and treat the wounded. Then something exploded on the bridge. With a roar and a shockwave, Herring’s field of vision went white. The starboard side of the tower blew apart, hurling him aloft. The ship’s mast tumbled overboard, taking the flag. The 449 shuddered and slowed, then sat motionless.

It was 10:59.

The first mortar round had destroyed the bow 40mm and set the ship afire. The second had knocked out the remaining 40mm gun. The third was simply catastrophic. Bedell was on the fantail. As chunks of steel flew overhead, a body fell 10 feet from the bridge to the gun deck. Bedell ran to the man. It was Herring, unconscious but breathing, left shoulder ripped open, jagged bone ends poking from the wound. Around them other men were getting up.

“Find Beuckman!” Bedell barked.

Defenders at coastal guns ashore had the 449 in their crosshairs; even machine gunners on Iwo were bringing fire to bear on the gunboat, which was not alone in its torment. A large-bore round had hit the 438. The 450, 474, 441, and 457 had taken multiple artillery strikes. Bedell could see smoke and flames pouring from the other LCIs, though they were maintaining position. The 449 could not withstand a hit from another enemy shell.

BEDELL NOTICED SOMETHING. THE SHIP WAS NOT moving. He headed for the pilothouse. From forward, so did Boatswain’s Mate Second Class Frank Blow. The two reached their destination at the same time.

“Do you know why we’re not moving?” Blow asked.

“I have no idea,” Bedell said. “I’m going to find out.”

He swung open the door. Silver spears of light streamed through holes in the bulkhead, illuminating a shattered space enough to reveal horrors. To Bedell’s left, in a chair by the 449’s communications center, was Radioman Lawrence Paglia, or what was left of Paglia. His arms hung limply, blood dripping from the fingers. His head was gone. Two sailors, maimed but alive, lay on the floor. Bedell had the urge to slam the door and vomit, then realized someone was at the helm. Lieutenant (junior grade) Robert Duvall was standing there staring blankly, clearly in shock. Blood was soaking his trousers and streaming to the deck. Duvall’s hands shook as he grasped the controls, trying and failing to get his body and his ship to respond.

Bedell could not sail the 449, but Blow could. Duvall was their superior; shoving him aside could be good for a court martial. “Duvall,” Bedell said. “Get out of there and let Blow in.”

Duvall stood trembling and silent. Blow stepped gently to the young officer and peeled his fingers from the steering mechanism. He shepherded Duvall out of the pilothouse, where he found several sailors to take him in hand. When they had gone, Bedell returned to the ruins. He opened the portholes. “Get us out of here,” he said to Blow.

The boatswain’s mate gave a thumbs-up. Blocking out everything around him, he scanned the gauges and cracked his knuckles. He let out a low whistle as he reached over to grasp the handles of the engine order telegraph, moved them to “ahead full,” and was delighted to hear the bell that meant the men in the engine room had received his order. In seconds the ship shuddered beneath him.

The engines roared. The 449 began moving again.

Blow slowly steered the gunboat until Iwo Jima was at its stern. They had solved one problem. There were others.

They needed a hospital ship, and soon. But the only friendly vessels in the vicinity were the destroyers and other fire-support ships, which were blasting the shore to protect the demolition teams. Blow put his head down and felt the 449 reaching a maximum speed of 12 knots—not fast, but better than standing still.

OF THE 449’s SEVEN OFFICERS, BEDELL WAS THE only able-bodied man. He checked on the wounded in the mess deck, then bolted to the pilothouse where Blow stood, eyes straight ahead, hands at the helm. With no radio, they could not find a vessel able to take some or all of the gunboat’s dozens of casualties. Scanning the horizon, Bedell tapped Blow’s shoulder. “Frank,” he said, pointing east. “Do you see that ship?”

Blow squinted.

“Yeah,” he said.

“Take us to her,” Bedell said. He did not know which ship it was, only that it was out of danger and large.

Now Bedell had to communicate with other vessels. The mast had carried off the antenna. Gunfire had smashed the signal light. They had one hope: semaphore. The 449’s crew included three signalmen. Bedell checked with Beuckman, who said one was dead, another unconscious and near death.

“How’s Arthur Lewis?” Bedell asked.

Beuckman shook his head. “Listen, Leo, his legs are shredded,” he said. “His abdomen is really tore up.”

Beuckman said if Lewis was conscious, they could ask him to help, but he wasn’t going to force him. Bedell agreed. Lewis sprawled on a mess deck table, reeling with pain from many wounds. Beuckman had done what he could for the signalman’s lesser injuries and put tourniquets on both his legs, but they were still bleeding.

With men hovering nearby, Bedell told Lewis the radio was shot. They needed…

Before Bedell could finish, Lewis responded: “I’ll do it.”

“Find me something Lewis can use as a flag,” Bedell said. Men turned up a fistful of dishrags. Lewis glanced at the mass of cloths. They would work.

His shipmates carefully lifted the signalman by the arms and carried him out, up two ladders, and over slippery decks to the bridge. Another gunboat, the 346, had come within a few hundred feet; Bedell decided to take a chance.

The men hoisted Lewis to their shoulders. He began waving the rags, using a visual alphabet 150 years old: “Urgent … Multiple casualties … Immediate medical help needed …” He squinted for the other LCI’s response, watched raptly, then glanced down at Bedell. “Sir, they state they will get help for us,” he said.

The 449 needed help now.

“We’re going to keep going,” Bedell shouted.

THE BATTERED GUNBOAT, angled from ship to ship, encountering none with medical personnel and space enough. The minesweeper USS Terror, though, looked like pay dirt with its huge crane and forest of communications antennas that indicated manpower and resources; plus, a pennant declared the Terror was a command vessel. Blow was edging the 449 into parallel to the other ship, intending to raft up, when men along the minesweeper’s rail frantically began waving him off. Someone had noticed the gunboat’s ramp and its five dozen high-explosive rockets, armed for firing and about to be sandwiched between the ships.

Despite the urgency, Bedell knew he had to take the safe path. He had Blow withdraw the 449 so crewmen could empty the launchers and, one by one, loop lines around each rocket and gingerly lower the projectile to the seabed. When the last rocket was stowed safely, the battered gunboat pulled alongside the Terror.

Nearly 90 minutes after the first mortar round struck, the 449 was safe.

IN ITS 36 DAYS, THE BATTLE FOR IWO JIMA CLAIMED 26,000 American casualties, including 6,800 dead, and 22,000 Japanese, all but 216 of whom died. Joe Rosenthal’s Associated Press photograph of U.S. Marines and a U.S. Navy corpsman atop Mount Suribachi immortalized the struggle, and in the decades since, historians, filmmakers, and scholars have analyzed and celebrated aspects of that monumental conflict.

Events two days before the invasion are a footnote, nearly forgotten. But without the reconnaissance mission, the death toll would have been much higher. The Japanese attack on the gunboats boomeranged on the enemy by revealing their gun emplacement locations; a day later, U.S. Navy battleships pounded those positions.

“Without this error by the Japanese, it is probable that many threatening coast defense weapons would have remained to take a very heavy toll of men and supplies from the outset of the ship-to-shore movement,” Jeter A. Isley and Philip A. Crowl wrote in The U.S. Marines and Amphibious War, Its Theory and Practice in the Pacific.

The U.S. Congress awarded 27 Medals of Honor for valor during the Iwo Jima campaign, more than any other single operation of the war.

The first of those medals went to Lieutenant (junior grade) Rufus Geddie Herring.

In addition, the navy presented Silver or Bronze Stars to seven other 449 crewmen, including Ensign Leo Bedell, Signalman Arthur Lewis, Pharmacist’s Mate Henry Beuckman, and Boatswain’s Mate Frank Blow. And LCI(G) Group Eight received the Presidential Unit Citation, one of the highest military awards, for “extraordinary heroism” on February 17, 1945, in support of the Underwater Demolition Teams.

“Only when the beach reconnaissance had been accomplished, did LCI(G) Group Eight retire after absorbing…devastating punishment,” the award said. All told, 43 men in Group Eight died; 152 were wounded. The 449 was the hardest hit—20 killed, 21 wounded—nearly two-thirds of its crew.

Survivors kept the battle before the battle to themselves, trying to put it behind them. Many couldn’t, and spent their lives haunted by what that day’s duty brought them.

“When you live with something like that, it stays with you forever,” Bedell said. ✯

This story was written by Mitch Weiss, and was originally published in the May/June 2016 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.