ON AUGUST 3, 1944, AS WORLD WAR II STILL RAGED IN MAINLAND EUROPE, Royal Air Force Captain Geoff Wikner set out to deliver an Avro Lancaster from Strathaven, England, to the RAF Scampton air base in Lincolnshire. Wikner wanted to take advantage of the clear skies and good visibility that day and test his first engineer on the plane’s feathering routine: The engineer had to position two fingers under the feathering button and yank it out at just the right moment, preventing the bomber’s engines from overrunning their maximum revolutions.

The exercise went smoothly until the plane suddenly veered to port. The engines had cut out. Thinking fast, Wikner immediately maneuvered the Lancaster toward the nearby Skellingthorpe airfield. He came in too high and too fast, but he wrestled the Lancaster down safely for an emergency dead-stick landing. Then, just as he hit the runway, the bomber’s engines suddenly roared back to life.

Wikner was left to wonder what had caused the anomaly. Was it mechanical error? Or was it the handiwork of one of those devilish gremlins he had heard about from other aviators who had experienced similarly freakish incidents?

Mark Sheldon, one of Australia’s top fighter pilots, was among those who believed that gremlins weren’t just optical illusions or figments of the imagination. “The whole thing is, they more or less reflect your mood,” he once explained. “If you fly carefully and well, they treat you good; if you fly badly, they act badly by you.”

THE EARLIEST REFERENCE TO THE AERIAL MISCHIEF MAKERS THAT WOULD COME to be known as gremlins may have been in The Spectator, a British magazine, which noted just after World War I that “the old Royal Naval Air Service in 1917 and the newly constituted Royal Air Force in 1918 have detected the existence of a horde of mysterious and malicious spirits whose purpose in life was…to bring about as many as possible of the inexplicable mishaps which, in those days as now, trouble an airman’s life.”

In the 1920s, sporadic reports began filtering in from RAF pilots in Malta, the Middle East, and India of “gremlins” attempting to harm them and their flying machines. An entry on gremlins in The Standard Dictionary of Folklore, Mythology, and Legend notes that “it was not until 1922 that anyone dared mention their name.” A British pilot who crashed into the sea in 1923 specifically blamed gremlins for the accident, citing cockpit chaos and engine sabotage. In April 1929 the journal Aeroplane published a poem that called gremlins a flyer’s nemesis. In 1939 the word made its first appearance in Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, which cited as a reference incidents in India reported by RAF bomber crews.

It is one of the most storied of aviation legends: the idea that flying machines are sometimes infested with nefarious gremlins—“little people” who tinker wantonly with various aircraft components. Endlessly creative in their antics and completely devoid of scruples, their devilment seems to know no limits. Physical descriptions of gremlins vary widely, though oddly enough, few airmen have claimed to have actually seen one. Gremlins are usually said to be about a foot tall, with long noses and brightly colored skin, most often hues of green or blue. Especially large feet with suction grips allow for walking in and outside the plane. The gremlins’ overall features are cartoon-like. They wear parts of vintage flight gear and bug-eyed goggles, although, as with other cartoon characters, clothing can be optional. They invariably sport wild and devious expressions when on their appointed rounds. All have magical powers.

Fanciful tales of gremlin-like creatures abounded long before the aviation era, of course. European folklore is filled with stories of such mischievous imps as elves, fairies, and goblins, all of whom interfered with human life—sometimes playfully, sometimes maliciously.

The etymology of the word “gremlin” is murky. Some say it derives from the Old English greme or gremian, meaning to vex or annoy, which was then coupled with goblin. But there are other plausible explanations. In Irish Gaelic gruaimin can mean “ill-tempered little fellow.” The German gramlein can be rendered into something like “a small bit of grief.” Even Fremlins, a British brewery established in 1861, has found its way into the mix of theories. In the late 1930s, one story goes, an RAF bomber command unit in India coined the word by combining Grimm’s Fairy Tales with Fremlins beer, the only brand available there.

With the advent of the Industrial Revolution, gremlin ancestors began to acquire and hone skills as craftsmen, benevolently helping Robert Fulton perfect his steamboat, Benjamin Franklin in his kite-flying electrical experiments, and so forth. But with the dawn of the air age in the early 20th century, gremlins metamorphosed into something more sinister. When World War I broke out, inexplicable events began to occur in and around the new flying machines, a sure sign that this particular strain of medieval gnome had quite literally spread its wings and flown into the latest technology.

And once one or two of the aerial trolls were reported on the prowl in the ranks of the RAF, they multiplied like rabbits. Seemingly offended by the very existence of aircraft, gremlins approached their work on the widest possible front. Previously reliable engines failed to catch when a mechanic propped the propeller; storage batteries were unaccountably drained of juice; fuel that had been carefully filtered through chamois still clogged carburetors; nuts came loose on critical bolts even when mechanics swore they had been firmly tightened; and landing gear wouldn’t lock down, causing crashes.

The gremlins also vexed flight crews. Extra maps placed in kit bags somehow vanished in flight, particularly on occasions when a faulty compass forced a crew off a planned course; a mysterious wrench would be found next to the magnetic compass; and a perfectly good sextant would abruptly lose its bubble level midway across an ocean. When wireless radios were first installed in aircraft, gremlins clapped in glee; there was no end to the ways in which they could distort reception and fill frequencies with static.

THE GENERAL BREAKOUT OF THE GREMLIN LEGEND BEGAN IN THE EARLY YEARS OF WORLD WAR II. Leading up to and during the Battle of Britain in 1940, with dominion pilots from Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and South Africa taking part in defending the Home Isles, their various cultures jelled into a coherent fighting force that began to weave previous gremlin accounts from the various British air services, as passed down through the far-flung squadrons in the eastern empire, into the RAF’s newfound élan.

The mystique and mythology of the creatures steadily expanded. In April 1942 came an article in the Royal Air Force Journal, by Hubert Griffith, a former pilot in the Royal Flying Corps, titled “The Gremlin Question.” Griffith humorously related how he had recently found himself attached to an RAF wing in northern Russia. He had never heard of gremlins until his flying mates schooled him on the matter. “They operate in droves or swarms,” he recalled being advised. “One imagined them [as a] procession of rats led by the Pied Piper of Hamelin.”

Griffith was further told that there were “Mediterranean Gremlins as well as East Fifeshire Gremlins” and that pilots throughout the RAF “seem to be on nodding terms with them.” He was assured that the gremlins were not always malevolent, that they could be playful and have a sense of humor. “Who could actually draw the outline of a Gremlin?” Griffith asked rhetorically. “Is he a ‘presence’ rather than a personality, a spirit than an embodiment?”

Soon gremlins began hitching rides on American aircraft. In August 1942, a report in the Camden (New Jersey) Courier Post suggested that the creatures were “now at work on the U.S. Army Air Force.” What may have been the first appearance of a gremlin in an American aircraft was reported by Sergeant Z. E. White, a waist gunner aboard the B-17E Flying Fortress Big Punk, who said his gun had jammed just as he sighted down on a German fighter plane during a battle over the North Sea. After landing, White related the story to Pilot Officer Oscar Coen, one of the original three members of the RAF’s American Eagle Squadron, and “a noted Gremlinologist.” Coen nodded and simply said: “Gremlins.”

That same year, American journalists in England attached to the newly arrived U.S. Eighth Air Force—most notably Peter Edson and Gladwin Hill, members of “The Writing 69th”—filed a number of newspaper stories about gremlins, introducing them to the American public. (Also known as “The Flying Typewriters,” the journalists trained to fly and accompanied bomber missions over Germany.) According to Hill, gremlins were bat-eared, long-nosed, garishly costumed creatures who “live in nooks but are allergic to crannies…Habitat: Obscure, but a large colony is known to exist between Whitechurch and Newbury, probably in a rubbish dump.”

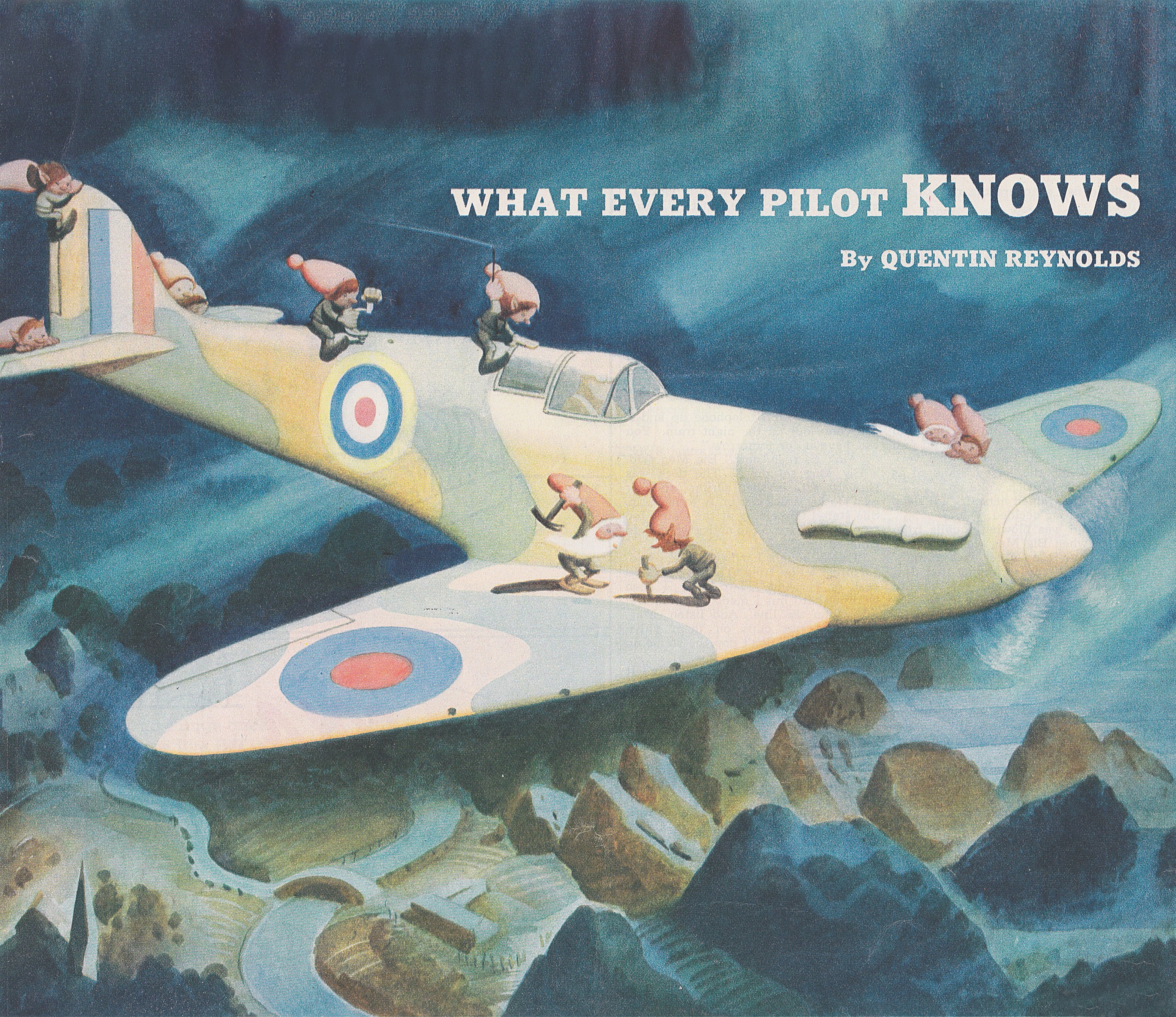

At about the same time, Quentin Reynolds, the celebrated American war correspondent, also took note. In an article for the October 1942 issue of Collier’s magazine titled “What Every Pilot Knows,” Reynolds revealed “the real reason for the [gremlins’] fiendish warfare.” It was, he wrote, because “the RAF lads made one mistake—they laughed at the Gremlins, and the fact is the Little People, above everything else, do not like to be laughed at.” He recounted one day hearing a mysterious soft voice—which may well have belonged to a gremlin—advising him that there was only one solution: “You’ll have to get the RAF to stop laughing.”

And before they became famous B-29 men, the three key airmen on the Enola Gay—Paul Tibbets, Tom Ferebee, and Dutch Van Kirk—played a role in expanding the mythos while serving aboard Flying Fortresses together in Europe. In 1942 Tibbets’s crew was debating a name for their new B-17F when their rather cerebral radio operator, Sergeant Orville Splitt, came across an RAF poem that enumerated the various domains of different colored gremlins. Because the poem made no mention of red gremlins, Splitt figured that they must be among the few “good gremlins.” The crew readily concurred, and thus one of World War II’s most famous B-17s acquired its name: the Red Gremlin.

Within the pilot community, it was probably the airmen of the high-flying Photographic Reconnaissance Units at England’s RAF Wick, RAF St. Eval, and RAF Benson that led the gremlin “publicity” charge. To bolster their own courage, or to somehow account for various malfunctions, or perhaps even to provide a bit of rear-end covering, these Spitfire pilots found it convenient to blame gremlins for nearly all their misfortunes. The most insidious of these gremlins were branded enemy agents. “There I was directly over the Abbeville airfield, the place filthy with Me-109s,” one of the pilots said, “when one of those bloody Hun gremlins jammed the camera toggle!”

THE MYTH BECAME WOVEN INTO THE FABRIC OF THE MILITARY AVIATION COMMUNITY. By the end of 1942, every airman in England—American or British—seemed to have his own gremlin story.

As stories spread among military units, the varieties of gremlins expanded exponentially. In a 1943 story in the Philadelphia Inquirer, journalist Chester R. Hope reviewed the variants as follows: “Jockeys” were able to sit cross-legged between the wings of a wayward seagull or pigeon and guide the bird into the windscreen of a fighter plane in flight. “Cavity types” had shovel-shaped noses that they used to dig runway holes in the paths of fighters or bombers coming in for landings, while “Incisors” chewed mercilessly on strut wires. “Puffs” used their big stomachs to suck air out from under wings, causing turbulence just as gunners took aim at their targets, spoiling their shots; similarly, “Optics” loved to hide in bomb sights, turning on the optic glow of their red or green eyes just as a bombardier was lining up his sights on a target. Above 10,000 feet, “Strato-gremlins” took over for the others. The members of this genus, Hope wrote, were “lined inside and out with fur in such a frosty blue tint that it creates virtual invisibility, and they carry oxygen tanks on their backs.”

Gladwin Hill wrote of bat-eared gremlins, or “duticulatus prangiferus,” that had sharp noses and elbow spurs for causing rips in wing fabrics and long teeth for gnawing fuel lines. Four-eyed gremlins, widely admired by RAF pilots, have two sets of eyes, one in front of their heads and one in back, allowing them to see in all directions at once.

Water gremlins, a genus that pilots would like to eradicate, specialized in disabling carburetors by spurting water into fuel lines. “Bombii” gremlins, the Associated Press reported in 1943, could “make a bomb turn handsprings and land far from the target.” Gremlin cousins called “Gablins,” according to another account, specialized in making “unthinking soldiers repeat vital military information to persons unauthorized to receive it.”

When the American Women’s Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs) was formed in 1943, the female flyers adopted the lady gremlin “Fifinella” as their mascot, complete with colorful insignia. Baby female Fifinellas were “Flippertygibbetts”; baby males were “Widgets.”

Young gremlins of both sexes had very high voices and chattered incessantly. Since they didn’t have suction boots like older gremlins, they typically stayed inside the aircraft and had fun knocking instrument gauges out of whack.

Gremlins, Hill playfully wrote, “weave their clothes out of pocket fuzz” and “live mainly off the stuffing out of the empty olives which are served in martini cocktails.” The top gremlin, the boss of all bosses, he said, was known as the “Grand Walloper.” Hope, just as playfully, wrote: “They live in little houses made of paper clips, which explains why paper clips, never known to wear out in use, must constantly be replenished.”

WHILE GREMLINS WERE AT FIRST MAINLY A MILITARY PHENOMENON, they established their first major beachhead in popular culture in 1942 when filmmaker Walt Disney penned a fanciful column that appeared in U.S. newspapers, accompanied by his own drawings, relating some of the tales circulating in the RAF. “Ever seen a real Gremlin?” Disney wrote. “No? Well, maybe it’s because you haven’t been up in a British Spitfire swapping bullets with a Messerschmitt, or dodging German flak in a bombing raid over Hamburg.”

The following year Roald Dahl, an RAF fighter ace and writer, put more wind beneath the gremlins’ wings. While serving as an assistant air attaché at the British Embassy in Washington, D.C., Dahl published his first children’s novel: The Gremlins, a fable of tiny creatures who flew on missions with Spitfire and Hurricane pilots. The book was a hit; so much so that Disney approached Dahl about turning it into a feature film.

With Dahl’s assistance, Disney Studios developed a series of gremlin characters and began preproduction on the film. During that time, Dahl recounted his own experiences with the creatures in a story that appeared in U.S. newspapers, featuring original drawings by Disney. But the film project stalled, partly because Dahl insisted that gremlins were exclusively an RAF icon and that he was their original creator. He insisted on final script and production approval, which prevented Disney from establishing formal rights to the gremlin story. Disney also felt that the involvement of the British Air Ministry, which had given Dahl permission to work in Hollywood and had a hand in the film contract, would prove unduly restrictive.

Walt Disney reluctantly abandoned the motion picture project but pursued his newfound fascination with gremlins in other ways. Issues 33–41 of Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories, published from June 1943 to February 1944, featured a nine-episode tale starring a character named Gremlin Gus, marking the first appearance of the creatures in comic book form.

Gremlins made other appearances in other pop-culture arenas during World War II. In addition to different versions of Dahl’s children’s book, Warner Bros. Studios—home of Bugs Bunny and Merrie Melodies—produced a number of colorful cartoon stories featuring gremlins.

A FEW “LONGHAIRS” AS PILOTS CALLED INTELLECTUALS, ALSO FELT COMPELLED TO WEIGH IN. In February 1944, at what appears to have been the high-water mark of gremlin activity, an article in The Journal of Educational Sociology asked: “What are some of the circumstances that have led so large a body of men to believe so vividly in the existence of…vicious little creatures that they are consciously aware of their actual presence under certain conditions?” Its author, Charles Massinger, went on to conclude there was little doubt that the gremlin phenomenon “can be considered pathological in its origin.…Both illusion and hallucination come under the general category of false-sense impressions [sic].”

Massinger was oblivious to the fact that pilots dearly love to “rag” the uninitiated. How sweet it must have been, after realizing a mark was vulnerable, to engage in a tall tale told in such earnestness that it seemed only to confirm the teller’s veracity. “Why that engine just up and quit on me and down we went!” a pilot might report. “Ol’ Tex—he’s my rear gunner, you know—why he yelled, ‘Skipper, say right now you believe in them Sparkplug Gremlins; say it out loud!’ Well, I did so and just before we hit the water, that big beautiful Allison fired right up and purred like a kitten all the way home.” The aviators became caught up in their own game and, without really realizing it, piled more wood on the gremlin fire.

By the end of the war, gremlins had become firmly entrenched in Western flying lore. In the years to come, their mystique would spread well beyond the military. Charles Lindbergh’s experience during his epic 1927 New York-to-Paris flight is a classic example. In his autobiography, The Spirit of St. Louis, Lindbergh related what happened to him during the most critical period of the crossing—the 21st and 22nd hour just before dawn, when he had been without sleep for nearly 48 hours. “The fuselage behind me becomes filled with ghostly presences…transparent, moving, riding weightless in the plane,” Lindbergh wrote. “I feel no surprise.…Without turning my head, I see them…clearly.”

He goes on: “These phantoms speak with human voices—friendly, vapor-like shapes, able to vanish or appear at will, to pass in and out through the walls of the fuselage as though no walls were there.”

Gremlins have also figured in many print, motion picture, and television treatments. In 1947 Dahl published Sometime Never: A Fable for Supermen, a serious, adult novel about a race of nature-loving gremlins trying to escape the human world of continuous warfare. A 1963 television episode of The Twilight Zone, “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet,” starring William Shatner, featured an evil gremlin attempting to rip an engine from the wing of the airliner in which Shatner is flying. The 1980s and 1990s saw a spate of gremlin-oriented films, including Steven Spielberg’s 1984 hit film Gremlins.

In 2006 a new generation was introduced to the gremlin mythos when Dark Horse Comics published The Gremlins: The Lost Walt Disney Production, a restored and updated print version of the never-realized World War II film, featuring an introduction by film historian Leonard Maltin. Dark Horse subsequently published a comic-book miniseries starring gremlin characters.

A special edition of Dahl’s original book was produced in 2007 to mark the 60th anniversary of the U.S. Air Force. Distributed exclusively through the Army and Air Force Exchange Service, it included a brief history of the book, and its dust jacket featured the air force commemorative anniversary seal. The initial print run sold out at all participating exchange service locations on the first day.

A final aspect that deserves consideration is an idea first advanced by Ernest K. Gann, the famed aviator and author. Gann suggested the possibility of an unseen, often capricious hand whose self-appointed purpose was to balance the yin and yang in human life—one man’s good fortune to be offset by his own or another’s grim fate. Why was he spared, Gann wondered, when his DC-4’s tail did not break off, while on the same day another pilot in an identical airplane, with the identical structural fault, suffered a fiery death? In his classic book Fate Is the Hunter, Gann labeled it as such—fate—for indeed, as he pondered, what else could it be? He was not fully satisfied with that conclusion, though he was never able to offer a better explanation.

Is it really so remarkable that early pilots, confronted with the poorly understood science of flying and themselves subject to sudden, unexplainable events, would feel the need to offer something tangible to account for why a friend suddenly perished and they were still happily flying? Would airmen not do what all humans have done for millennia when confronted with similar dilemmas—snatch the inexplicable away from the cosmos and give it form back here on Earth? After all, isn’t that why humans conjured fairies, goblins, gnomes, leprechauns, and their ilk in the first place?

Why not, then, add gremlins to the list? Gremlins offer one way, no matter how outrageous or weakly reasoned, to explain why a camera toggle switch suddenly freezes or one aircraft’s tail falls off and another’s doesn’t. In the end, it all comes down to taking a timid peek at the transcendent—a grasping, very human attempt to put a face on the Great Unknown. MHQ

Robert O. Harder flew 145 combat missions during the Vietnam War as a B-52 navigator-bombardier. A former commercial pilot and certificated flight instructor, he is the author of The Three Musketeers of the Army Air Forces: From Hitler’s Fortress Europa to Hiroshima and Nagasaki (Naval Institute Press, 2015).

[hr]

This article appears in the Autumn 2019 issue (Vol. 32, No. 1) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Gremlins!

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!