Inexperienced 126th New York mustered in three weeks before it surrendered on eve of Antietam

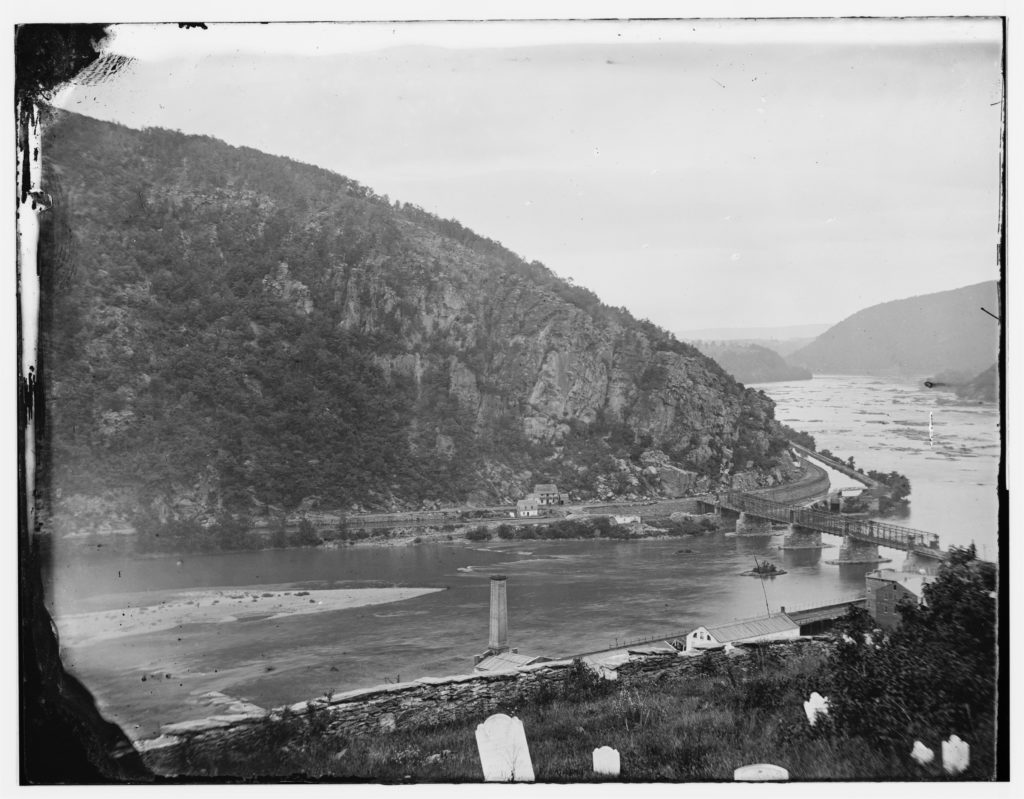

In its November 1862 report on the disastrous surrender of the U.S. garrison at Harpers Ferry, Va., two days before the Battle of Antietam, the Army commission investigating singled out the performance of one regiment as worthy of special condemnation, calling attention “to the disgraceful behavior of the One hundred and twenty-sixth New York Infantry.”

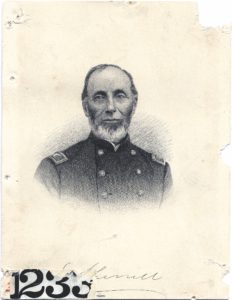

Recruited from the state’s Finger Lakes region, the 126th New York had been in service for barely three weeks when it was surrendered at Harpers Ferry on September 15, 1862. The 126th had been ordered to Harpers Ferry only a week after mustering in, along with the equally green 111th and 115th New York. In reality, the regiment consisted of uniformed and equipped civilians, with no training in marching, maneuvering, or in firing their weapons. Harpers Ferry seemed a relatively safe location for these regiments to gain some experience and train for field service. The 126th’s colonel was 49-year-old Eliakim Sherrill, a Geneva, N.Y., farmer and former U.S. congressman and state senator. Sherrill had dabbled in the state militia but admitted when his regiment was ordered to the defense of Maryland Heights on September 12 “that he knew nothing about military; that he made no pretensions to military; that he was just in the field and green, but if there was to be fighting he was ready to go.”

Sherrill’s unit drew the unlucky assignment of providing reinforcements to Maryland Heights, key to the defense of Harpers Ferry and currently threatened by an advance of two brigades of Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws’ Division. The march to the summit was grueling for the green soldiers. As Company E Private Marcus Andrus wrote his sister: “The distance from our camp on Bolivar Heights to Maryland Heights is about four miles, and over one of the worst roads to travel that ever lay out doors. We were nearly three hours in reaching there, and a more tired, hungry and thirsty set of mortals you never heard of in your life.” Sherrill was missing some 200 of his men, who were on picket and could not be recalled before the regiment marched. This left him about 800 effectives.

The commanding officer on Maryland Heights was 32nd Ohio Colonel Thomas H. Ford. Because Ford was physically immobilized due to recent surgery, he delegated tactical command of the troops facing McLaws’ advance to his major, Sylvester M. Hewitt. Neither man was a gifted leader. Ford and Hewitt had a large area to defend, but they compounded their problems with a ruinous system of detaching individual companies for various duties. That wasn’t a serious problem for veteran troops but was a recipe for disaster for a raw unit such as the 126th. Individual companies and their officers had no experience in deploying skirmishers or other elemental operational duties. Hewitt took two of Sherrill’s companies for one mission and three others for another, halving the 126th’s strength.

The balance of the regiment marched north to where Union skirmishers were sparring with Confederates of Brig. Gen. Joseph Kershaw’s South Carolina brigade. Hewitt led the 126th to a position in rear of the skirmish line and for the first time the regiment formed a line of battle. This was not a drill field but a dense wood with gunfire exploding a short distance away. The enemy could be heard but not seen. Bullets clipped through the trees. Sherrill thought the situation worrisome enough he recalled two of his companies that Hewitt had detached.

The skirmishing ended at nightfall, but resumed about 7 the next morning. Utterly unprepared for combat, the 126th greatly exaggerated the strength of the enemy in its front—15,000, Private Andrus would write—and performed poorly. “All we could do was ‘skedaddle’ for our own breastwork,” about a mile in the rear, Andrus wrote. In reality, Kershaw had only about 1,200 men, but they were experienced veterans.

herrill and his adjutant, Lieutenant Samuel Barras, beat their stampeding regiment in the race to the breastwork, a log work that stretched across the summit of the mountain. The path along the mountain spine passed through an opening in the works. Sherrill and Barras positioned themselves here and managed to rally most of the regiment as it arrived behind the works. This was the best possible circumstance for the New York rookies. They had good cover and did not need to maneuver. They were also buttressed by parts of more experienced regiments, such as the 32nd Ohio and 39th New York.

The battle renewed and, according to Andrus, “we had a pretty lively time of it.” Sherrill proved exceptionally—and rashly—brave, climbing up on the log works to shout encouragement to his men. When someone warned him he was exposing himself too much, he thundered, “G_d d__m the exposure: no rebel ball can hit me.” But they could. A bullet struck him in the lower jaw; a bloody, frightening wound. His fall further shook the confidence of his men, though they fought on. Minutes later it was learned that another Confederate brigade, Brig. Gen. William Barksdale’s Mississippians, was threatening the right flank of the barricade defenders. Shaken by the news, Major Hewitt fatefully sent orders for the men to fall back. Confusion reigned at the barricade, where some officers, knowing the strength of their cover, tried to keep the men at the works. Eventually though, the defense collapsed and everyone, rookies and veterans, streamed to the rear.

Andrus was furious when he later read in a New York newspaper that his regiment was the first to run from the barricade and the cause of the Union defeat on Maryland Heights, writing, “All I have to say about this is that it is a downright lie!” The first ones to run were the famous Garibaldi Guards and the next were the Ohio boys. This I know to be a fact, as I was there and saw the whole of it.” The truth was that any of the new regiments in the Harpers Ferry garrison placed in the position the 126th found itself would have suffered the same outcome. The commission’s censure of their performance deflected responsibility from the real culprit of the debacle: a system that placed them in harm’s way before they were trained.

Over the next nine months, the 126th would hone itself into a well-trained fighting unit and redeem its reputation at Gettysburg.

Scott Hartwig writes from the crossroads of Gettysburg.

This story appeared in the May 2020 issue of America’s Civil War.