As war clouds gathered over America, Israel Washburn, Maine’s newly elected governor, downplayed the danger to the republic in his inaugural address on January 3, 1861. “We are told that the slave States, or a portion of them, will withdraw from the Union,” he said. “No, they will not. They cannot go, and in the end will not want to go…they will not pass the brink of the precipice….”

Washburn, of course, was overly optimistic, and Maine, like the rest of the Union, was unready for the unfortunate conflict. “The bombardment of Fort Sumter at Charleston…found Maine as little prepared to furnish troops for maintaining the integrity of the Union as it is possible to conceive,” reported John Hodsdon, the state’s adjutant general.

Governor Washburn called together a special session of the legislature on April 22 and the lawmakers authorized raising $1 million and enlisting 10,000 men to fill 10 regiments. Four of them would be ready to fight at Bull Run, Va., the first major battle of the war. The 2nd Maine, commanded by Colonel Charles Jameson, became the first regiment to leave the state. West Point graduate Oliver Otis Howard took command of the 3rd Maine. The commander of the 5th Maine was Mark H. Dunnell of Portland, a lawyer and a one-time legislator. When the war began, Dunnell was the U.S. consul in Veracruz, Mexico. His patriotism aroused, he received permission to return home, where he helped raise the regiment and was elected colonel.

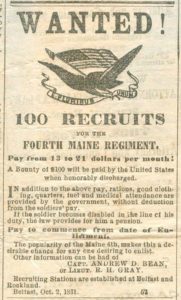

The 4th Maine was commanded by Hiram Berry, from the harbor town of Rockland. At a public meeting to raise men for the 4th on April 23, someone tossed a $20 gold coin on the floor and said it would go to the first man who volunteered. Stephen H. Chapman, a strapping 6-foot-plus tall, picked up the coin. He later became Berry’s sergeant major.

When the 4th Maine left Rockland on Friday, June 17, 1861, enthusiastic throngs of citizens cheered the soldiers as they marched down to the town wharf in their new gray uniforms. Crowds greeted them in Boston and when they reached New York. The troops marched up Broadway and the Sons and Daughters of Maine, natives of the state residing in New York, provided a reception and presented flags.

Then it was on to Philadelphia. “The pretty waiting maids were very attentive to the wants of the boys from Maine, who were ready to affirm that the girls of Philadelphia could not be excelled except by those of the Pine Tree State,” wrote Berry’s biographer.

Baltimore, a hotbed of secessionism, offered a cooler reception. Berry distributed ammunition to his men just in case. The 4th Maine made it peacefully through the city, but Berry noted that “dark and sullen” men lined the streets.

Oliver Otis Howard and the 3rd Maine had a reasonably uneventful trip from Augusta to Washington, D.C. The soldiers disembarked from a steamer in New York City in a pouring rain. Members of the Sons and Daughters of Maine waited at the dock to escort them up Broadway to the armory on White Street, and presented the regiment with a flag. Howard received his first war wound during the ceremony. The surging crowd jostled him off the gun carriage he had been using as a speaking platform and his heavy saber crushed his big toenail when he hit the ground.

Colonel Howard reasoned that his regiment must be drilled and made ready for war

George Rollins enlisted in Company G as a private when he was only 17, and he was having a grand adventure so far. “I had the best time in Boston,” he wrote to his father. “I never saw so many people before. From the depot to the Common the streets were so crowded that the policemen could hardly make way for us….[I]t was a vast sea of faces.” In New York, though, Rollins experienced the differences between the officers and the enlisted men. The officers were taken to dinner at the Astor House, while the enlisted men were left to fend for themselves. “We made ourselves as merry as possible but there were some sour looks,” Rollins said.

Like other regimental commanders who had come before him, Howard had his men load their weapons when they reached Baltimore. He was surprised to find that the people there seemed cheerful as they watched his men march by, although he did notice there were no U.S. flags flying from any of the public buildings.

In Washington, Howard picked up the tab (50 cents apiece) for breakfast for his men at the Willard Hotel, and reported to General Joseph Mansfield, who commanded the Department of Washington. That night, Howard remembered, in their camp on Meridian Hill, one soldier badly injured himself when his own musket discharged.

Corporal Abner Small, however, claimed that Howard had forgotten to have the regiment unload its weapons after leaving Baltimore, and one soldier accidentally shot the man in front of him. When Howard then had his men discharge their weapons into the air, a number of their bullets riddled tents of the nearby 2nd Maine, fortunately without injury. No matter how the incident evolved, it was a sign that the soldiers were green.

Howard also had to get his independent-minded soldiers to submit to military discipline. “One moment we were free men to go and come as we pleased, and the next saw us amenable to all the arbitrary and despotic rules of the war department,” remembered one soldier. After learning that some of his free-spirited men violated their furloughs, Howard stopped issuing passes. “The regiment must be drilled, disciplined, and made ready for war,” he reasoned.

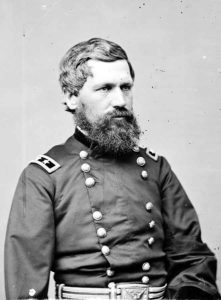

The Rebels weren’t the only enemy these new soldiers had to combat. Disease was an ever-present danger. Fortunately for the 3rd Maine, one of the people traveling with the regiment was Sarah Sampson of Bath, the wife of Charles A.L. Sampson, the captain of Company D. Mrs. Sampson had decided to “devote herself to the welfare of the sick without any assurance of recompense.” At the end of June, Howard fell seriously ill with cholera and for a time lay at death’s door, with Sarah Sampson caring for him. Once he recovered, Howard learned that he would be commanding a brigade made up of the 3rd, 4th, and 5th Maine and the 2nd Vermont. Major Henry Staples of Augusta took command of the regiment.

Howard’s brigade belonged to the division commanded by plain-spoken Colonel Samuel P. Heintzelman. Howard’s soldiers were green, but certainly not the only ones unready for war, as Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell knew only too well. McDowell was the general who would lead the new Union army—christened the Army of Northeastern Virginia—in the first major battle of the war.

Before the war he had never commanded more than eight soldiers in the field; now he had to handle an army of 35,000. In addition, McDowell lacked the necessary equipment and transportation to get his army into the field in a condition necessary for combat. It didn’t matter. There was a growing popular clamor for the Federal army to put an end to the crisis. On July 16, after some delays, the reluctant McDowell began moving forward. That day George Rollins wrote, “I am about to go off on a march, and have a few moments time to write,” he said. “Our Div. (the second) is getting together and are going on to Richmond, that is eventually—but have got to clear the way first.”

McDowell’s target was a force calling itself the Army of the Potomac, under the command of General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard. Its 22,000 men held positions near the impor-tant rail junction of Manassas, about 22 miles from Washington and behind a wandering creek called Bull Run. McDowell’s army set out on a slow progress toward battle in four separate columns. Brigadier General Daniel Tyler’s division, which included the 2nd Maine, was to the north, where it would pass through Vienna; Colonel David Hunter was south of Tyler, aiming straight toward Fairfax Court House; Colonel Dixon Miles’ division turned farther south to follow the Braddock Road toward Centreville. Heintzelman, the farthest south, followed a road that roughly paralleled the Orange & Alexandria Railroad.

One of Howard’s men was mortally wounded when he grasped his loaded musket by the muzzle so he could knock an apple from a tree. The pious Howard also fretted because he thought his men swore too much. “I wish we had men who had more respect for the Lord,” he wrote to his wife on July 18. “We might then expect his blessing.” He had other problems with his men, too. Unaccustomed to long marches in the hot sun with all their heavy equipment, they began to fall out of the ranks and straggle. Some left their formations to pillage the homes they passed.

In addition, the Union forces had to clear obstructions that the retreating Rebels had left in the roads, further slowing things, while the untried commanders feared ambushes and moved “as timidly as old maids eating shad in the dark,” as Abner Small put it. The result was a slow, disorganized approach toward Manassas that gave Beauregard plenty of time to prepare.

In the meantime, General Robert Patterson was supposed to prevent the Confederates in the Shenandoah Valley under Joseph Johnston from reinforcing Beauregard. But Johnston managed to slip away from Patterson, and his men began arriving in Manassas by railroad on July 20. McDowell’s plans were already starting to unravel.

Hiram Berry, commanding the 4th Maine in Howard’s division, scratched out a letter home on July 18. “We are now only eight miles from Manassas Gap, and bound thither, enemy in front all the way, trees across the roads, bridges all burned, etc. Hard labor to clear the way.”

It was still dark the morning of July 21 when the Union forces broke camp for their offensive. The divisions began to get into each other’s way almost immediately, creating gridlock on the roads. Howard’s brigade, in the rear of Heintzelman’s division, did not lurch into motion until long past daybreak. Before long, men were falling out of ranks to sit down by the side of the road and rest. Later that morning, Heintzelman selected Howard’s men to serve as a reserve force. Waiting behind the lines for their first taste of combat, they could hear the sounds of battle growing in volume. “I cannot forget how I was affected by the sounds of the musketry and the roar of the cannon as I stood near my horse ready to mount at the first call from McDowell; for a few moments weakness seemed to overcome me and I felt a sense of shame on account of it,” Howard recalled. “Then I lifted my soul and my heart and cried: ‘O God! enable me to do my duty.’ From that time the singular feeling left me and never returned.”

An aide from McDowell arrived with orders for Howard to advance, and he moved out at the double-quick. “The blankets began to fall, and everything impeding the progress of the men was cast aside as worthless,” remembered George Rollins. More and more soldiers collapsed. “Men seemed to fall in squads by the roadside, some sun-struck, some bleeding at nose, mouth, ears; others wind-broken, while others were exhausted to such a degree, that the threatening muzzle of the officers’ pistol, failed to induce them a step further,” wrote a soldier in the 5th Maine.

“We kept hearing that our men were gaining the day and we would be there just in time to give the Rebels a farewell shot but…as we came upon the field we met our men in retreat,” wrote Rollins. “All this didn’t stop us, but on we went. Shells began to burst about us and cannonballs served to make us dodge a little but not to stop our progress for we hadn’t had a shot at the enemy yet.”

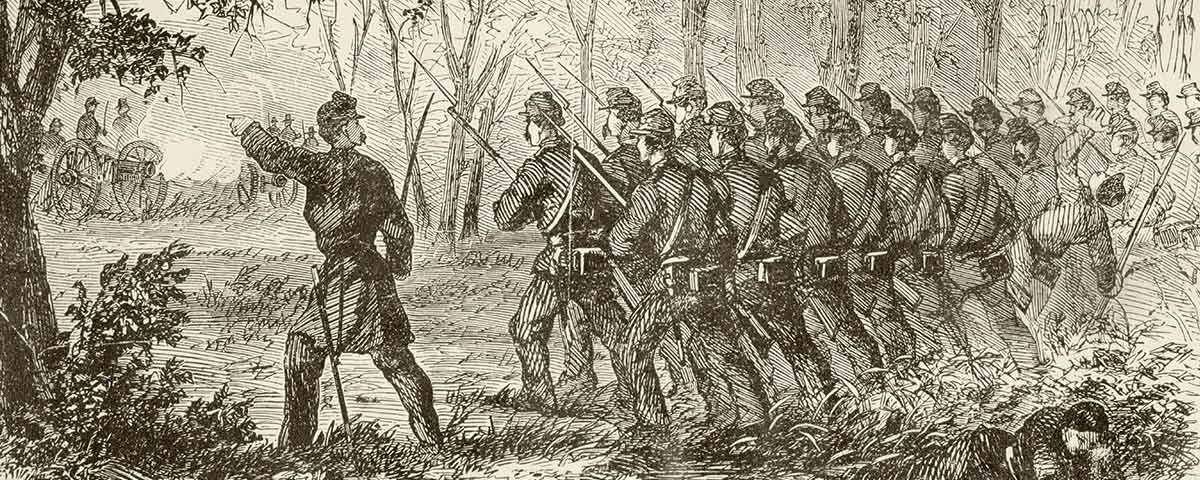

At the far right of the Union lines, on a rise called Chinn Ridge, Howard formed his brigade into two lines, the Vermont regiment and the 4th Maine in front, the 3rd and 5th Maine following. Howard, on horseback, watched his men as they went into battle. “Most were pale and thoughtful,” he recalled. “Many looked up into my face and smiled.”

Untried commanders feared ambushes and moved as ‘timidly as old maids eating shad in the dark’

It was around 2 o’clock on the sweltering July afternoon when Berry received Howard’s order to move the 4th Maine forward. The men who remained after the punishing march formed a line of battle and were immediately raked by enemy fire. The first man to fall was Sgt. Maj. Steven H. Chapman, who had picked up the gold coin at the meeting in Rockland. “Tell my wife I am shot—God bless her,” he murmured. Then he died, leaving five children fatherless.

Berry felt surprisingly calm during his first experience of combat. He did not believe he would be hit, and didn’t worry about it. Even as men fell to his left and right, he remained focused on his command responsibilities. When Chapman dropped, Berry took up the flag and held it. Bullets tore his clothing, and at some point one hit his horse.

Two Brave Brothers

on July 21, 1861, and became one of the Union’s 2,896 First Bull Run casualties.(Collections of Maine Historical Society)

The 5th Maine suffered its initial casualty at the First Battle of Bull Run when a cannonball struck Sergeant Alonzo Stinson, a baby-faced sergeant in Company H. His brother Harry, a private in the same company, remained with the dying Alonzo and was later taken prisoner. Alonzo’s body was never recovered, and the location of his remains is unknown. On July 4, 1908, Alonzo’s hometown of Portland dedicated a monument in Eastern Cemetery to commemorate him as the first soldier from the city killed during the Civil War. The image above is from the monument’s dedication ceremony, which was attended by Maine’s arguably most famous Civil War veteran, Joshua Chamberlain. The monument is in the shape of a hardpack knapsack with a blanket rolled on top, and is decorated with a bronze bas-relief sculpture of Stinson and a bronze tablet explaining his service and sacrifice. The memorial was cleaned and rededicated on June 2, 2001, Alonzo’s 159th birthday.

Harry Stinson was exchanged after Bull Run, and served as Oliver O. Howard’s aide de camp. On May 27, 1864, at the Battle of Pickett’s Mill, Ga., Captain Stinson stepped into the open to observe Confederate movements and was shot through the body. He returned to active duty in a few months, but died from the wound’s effects in 1866. Howard referred to Stinson as “good, true, and faithful and brave,” in an 1863 letter, and in 1869 he named his firstborn son Harry Stinson Howard to honor his former aide and friend.

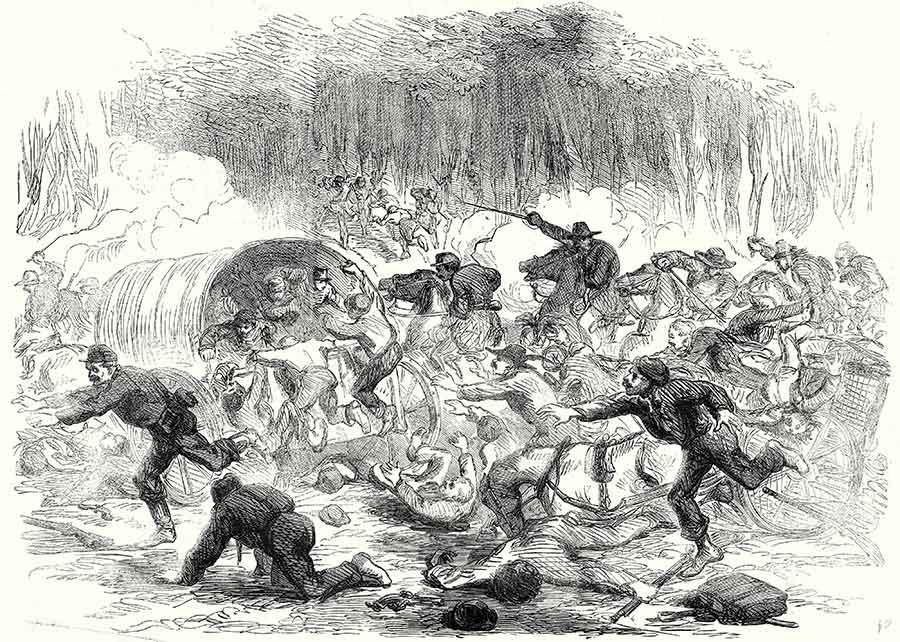

Howard brought up his second line, the 3rd and 5th Maine. “The next thing we knew, we were in the field on the hill and facing the enemy,” wrote Small of the 3rd. “I can only recall that we stood there and blazed away. There was a wild uproar of shouting and firing. The faces near me were inhuman.” Small saw a piece of solid shot kill one of his close friends, David Bates. “It was a hot place,” Howard wrote. “Every hostile battery shot produced confusion, and as a rule our enemy could not be seen.” Remaining on Chinn Ridge was obviously futile, and Howard ordered a retreat.

“We made a stand and fought the best we could with that battery raking us on the right and musketry playing upon us in front,” George Rollins told his parents. “Our men fought well and stood fire like heroes but it was of no use. All the other troops had left, and the Rebels were coming upon us in overpowering numbers so the order to retreat was given and we turned our back to the enemy. I don’t wish to say anything of what I saw on the field. God grant that I may never see the same again. Our retreat was all confusion and turmoil.”

The retreat turned into something just short of a rout. “Confusion, disorder seized us at once,” wrote the 5th Maine’s George Bicknell. “How we traveled! Nobody tired now. Every one for himself, and having a due regard for individuality, each gave special attention to the rapid momentum of his legs.”

Captain William S. Heath of Waterville, captain of the 3rd Maine’s Company H, walked alongside Howard’s horse in tears because his men would not obey his orders. At some point Heintzelman rode by, wearing a sling for a wounded arm, and swore at Howard for not keeping control of his men. Heintzelman must have sworn at many officers that day. Howard, of course, did not swear, and he simply tried to spread word that the brigade should fall back to its old campsite at Centreville. From there they made their way back to Alexandria.

Back on July 12, Private George Rollins of the 3rd Maine had written to his parents that he was “going to visit Jeff D. at his residence” and give the rebels “a stern rebuke.” Instead, the fighting at Bull Run had served Rollins and his fellow soldiers a cold dose of reality. “I don’t hope to get home now til the three years are up,” Rollins wrote to his parents afterward. “I have yet to see many more battles and endure many hardships before this war is brought to a close.”

Adapted from Tom Huntington’s book, Maine Roads to Gettysburg: How Joshua Chamberlain, Oliver Howard, and 4,000 men from the Pine Tree State helped win the Civil War’s Bloodiest Battle (Stackpole Books).