In service to the British empire in Canada and South Africa, American machine gunner Arthur ‘Gat’ Howard lived up to his rat-a-tat nickname

Subordinates may have regarded portly British Maj. Gen. Frederick Middleton as pompous and plodding. But the 59-year-old commander of the Canadian Militia—who had been recommended for the Victoria Cross during the 1857 Indian Rebellion and honorably mentioned in dispatches in New Zealand—was no fool. As he surveyed the western Canadian village of Batoche through his binoculars on May 9, 1885, the old soldier knew he was in trouble.

In late March, when the Métis people (of mixed-blood European and North American Indian ancestry) allied with disaffected Crees and Assiniboines of the First Nations to overthrow the government of the District of Saskatchewan, Middleton had hastily raised a force of some 900 Canadian militiamen to put down the uprising. Although the Métis were undisciplined fighters, they were skilled at irregular warfare and expert marksmen armed with Winchester repeating rifles.

Other than a few squads of scouts and constables of the North-West Mounted Police, Middleton’s force largely comprised citizen soldier units from cities and towns back East. Armed mostly with old breechloading, single-shot Snider-Enfield rifles, the militia was better suited to the parade ground than warfare against a resourceful, mobile enemy fighting on his own turf. “I went down the ranks,” the general himself recalled of one training drill, “and found that many of [the men] had never fired a rifle; some even had never fired any weapon at all.”

On April 24, en route to the Métis stronghold at Batoche, Middleton’s force had stumbled into an expertly laid ambush at Fish Creek. During the sporadic firefight the Canadians had lost 10 killed and 40 wounded, and Middleton took a bullet through his fur service cap. A week later the general had received word that First Nations warriors at nearby Cut Knife Hill had defeated an attacking force under his subordinate, Lt. Col. William Dillon Otter, with similar losses.

Now, as Middleton cautiously marched his men toward the high ground overlooking Batoche, he likely hoped for some advantage to tilt the momentum in his direction. Suddenly, puffs of smoke and the whistle of incoming rounds alerted him to enemy snipers firing from two wood-frame houses in the distance. Middleton called for artillery to shell the houses. As his men wheeled one of the column’s 9-pounder field guns into position, a lanky, bearded man in an unfamiliar blue uniform directed another gun carriage forward. Fixed atop it was a bundle of brass tubes that looked like some sort of plumbing fixture. Middleton’s advantage had arrived.

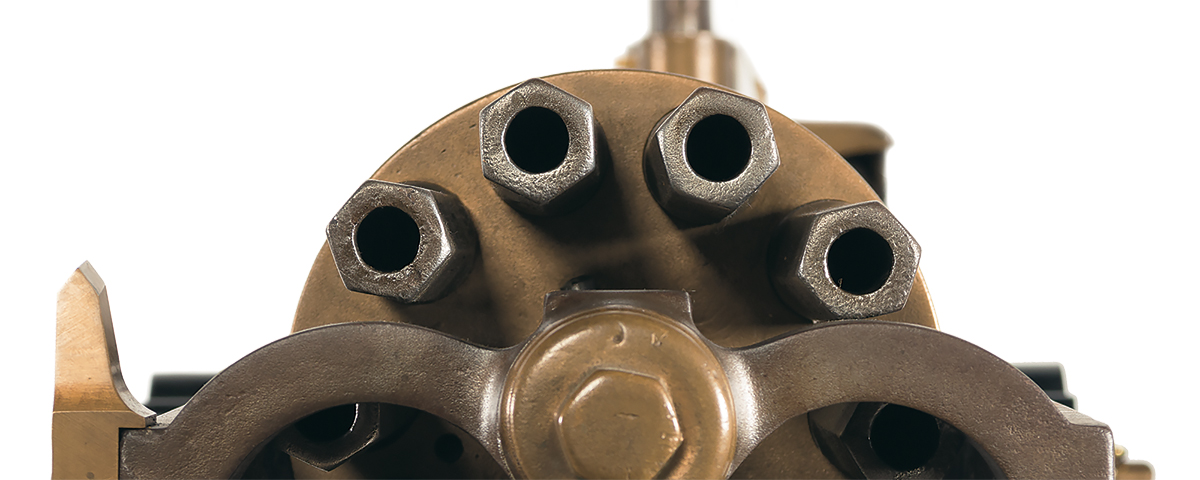

Lieutenant Arthur Howard of the Connecticut National Guard squinted down the gleaming topmost brass barrel and front sight of the new Gatling gun at his target, a cluster of two-story white houses beside a Catholic church a little over a half-mile away. Locking in the barrel, he cranked the breech handle, and the gun belched out fire and smoke, sending dozens of rounds ripping through the wooden structures. One caught fire, scattering its defenders. Seconds later from a window of the other house poked a white flag, waved frantically by its occupants—a huddle of priests, nuns and terrified Métis women and children. Though the target was somewhat questionable, the power and speed of Howard’s weapon had impressed Middleton and struck fear into the enemy snipers, who scrambled to find better fighting positions.

As Canadian forces resumed their advance on the fortified village, the Métis, firing from well-concealed rifle pits, halted the militia. The defenders also managed to thwart a prearranged flanking assault by the steamboat Northcote by lowering the town’s ferry cable across the river, which sheared off the ship’s masts and smokestacks, knocking it out of the fight. The Métis then mounted a determined counterattack to seize a battery of field guns, but Howard quickly positioned his Gatling gun to repel the assault. Major Charles Boulton recalled the episode in a postwar memoir:

‘Howard on this occasion showed his gun off to the best advantage and very pluckily worked it with great coolness’

The Gatling, which was being worked for the second time and was just getting into action, with…Howard at the crank, turned its fire on the concealed foe and for the moment silenced them.…Howard on this occasion showed his gun off to the best advantage and very pluckily worked it with great coolness, although the fire from the enemy was very hot for a time.

Middleton then directed Howard and his weapon to spearhead a flanking attack against the Métis. But even the superior firepower of the Gatling, which could send downrange some 400 rounds per minute, couldn’t dislodge the Métis from their stoutly constructed rifle pits. Neither side could gain an advantage as the day wore on. Finally, in the evening Middleton fell farther back to high ground and constructed a zareba, or improvised stockade, using the wagons and other barriers.

The next day, May 10, the Canadian force hardened the zareba’s fortifications and bombarded Batoche with the 9-pounders. On the morning of the 11th the general brought Howard and his Gatling with a squad of scouts on a reconnaissance in force to probe the Métis left flank. The Métis met each burst from the machine gun with steady return fire, ultimately forcing the party to withdraw to the zareba. But the general had gathered valuable intelligence on the enemy positions, thanks in part to the Yankee and his machine gun.

Middleton’s plan for the final assault was to employ Howard’s gun and one of the 9-pounders in a diversionary attack on the Métis left flank. On hearing the cannon’s initial rounds, Lt. Col. Bowen Van Straubenzie, commanding the bulk of the infantry forces, would lead the main attack on the Métis right flank.

At midmorning on May 11 the cannon and the Gatling gun opened up, which drew heavy fire from the Métis left flank as expected. However, due to strong winds Van Straubenzie never heard the cannon fire and failed to assault the right flank. When Middleton realized his plan had gone awry, he retreated to his tent in a blind rage, later admitting, “I am afraid on that occasion I lost both my temper and my head.”

What happened next is unclear. Either Van Straubenzie or Lt. Col. Arthur Williams or both then led an all-out infantry assault on Batoche, successfully dislodging the Métis, whose supply of ammunition was nearly exhausted. Three days later the Canadians captured Métis leader Louis Riel, whom they tried for treason and hanged. The Northwest Rebellion, as it came to be known, was over.

Canadian and British newspapers heralded the empire’s victory, and Queen Victoria herself knighted Middleton. Also lionized for his exploits, Howard earned the nickname “Gat,” which stuck to him for the rest of his life. But who was this Yankee soldier of fortune?

Arthur Lockhart Howard was born on Feb. 16, 1846, in Hinsdale, N.H., and attended school in Chicopee, Mass. At age 21 he enlisted in the U.S. Army at Carlisle Barracks, Pa. His enlistment form records his occupation as “machinist,” thus it’s conceivable the young New Englander was fleeing a life of industrial drudgery for the adventure of soldiering.

Howard served with the 1st U.S. Cavalry Regiment from 1866 to 1871. Existing records don’t refer to him by name, but the unit history indicates that regimental detachments engaged hostile Indian bands in Oregon, Idaho Territory, California, Nevada, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Arizona, including pursuit of the legendary Apache war chief Cochise.

Returning to New England, the young machinist worked for vaunted arms manufacturer Winchester in New Haven, Conn., even registering a few of his own patents. In 1881 he ventured out on his own and established the cartridge-making firm A.L. Howard & Co. Unfortunately, a fire destroyed the budding enterprise, though Howard soon found work with another cartridge manufacturer.

In the meantime, Howard returned to military service, joining the Connecticut National Guard in 1880 as a sergeant in the Governor’s Horse Guard. In 1884 he was promoted to lieutenant and given command of his regiment’s newly formed machine gun platoon. Around that time Howard came to the attention of Richard Jordan Gatling, inventor of the automatic weapon that bears his name.

When the Métis rebelled in 1885, the Canadian government sent Gatling an urgent request for his machine guns. Likely to ensure his innovation would be properly deployed, Gatling sought out Howard to accompany two guns to Canada. The Connecticut National Guard granted the lieutenant one month’s leave, though it stopped short of sanctioning his adventure in the Great White North. Gatling undoubtedly arranged some form of payment, as by then Howard had a wife and five children. In all associated paperwork the inventor refers to Howard only as “a friend of the gun.” The lieutenant had already earned himself a place of honor in Canadian military history for his stalwart actions at Batoche in May 1885. But his swashbuckling military career was far from over.

Following his exploits in the Northwest Rebellion, Gat Howard traveled repeatedly between Canada and the United States, eventually spending the bulk of his time in Canada. In 1886 he founded the Dominion Cartridge Co. in Brownsburg, Quebec, which manufactured ammunition for the Canadian government. Apparently, the travel put a strain on his personal life. After giving birth to their sixth child—a son named Van Straubenzie—wife Sarah refused to join Arthur in Quebec. In November 1888 a lurid article in the New Haven Evening Register described one tempestuous public encounter between Arthur and Sarah, reporting, “He had a very stormy interview with his wife and put into practice some of the tactics he learned while fighting Riel’s rebels.” By month’s end the couple had finalized their divorce.

Remaining in Canada, Howard became a prosperous businessman. In addition to the rapidly growing cartridge factory, he invested in various other business ventures, including a failed lobster processing plant in Labrador. He married farmer’s daughter Margaret Green in 1895 and built an impressive mansion in Brownsburg.

Another period newspaper account offers a glimpse into Howard’s fiery disposition. In the encounter it describes, he apparently accused the U.S. Customs officer in Halifax, Nova Scotia, of turning a blind eye to smuggling. After a “hot exchange of words,” the two men came to blows.

In 1899 Canada dutifully answered the call of the British empire to provide troops for the brewing fight against the Boers in South Africa. The 1st Canadian Contingent comprised 1,039 troops under Lt. Col. Otter of Cut Knife Hill notoriety. But the force proved insufficient to bolster the beleaguered British army, and Canada was asked to provide a second contingent.

At a time in life when many men look forward to retirement, Howard was willingly off to combat

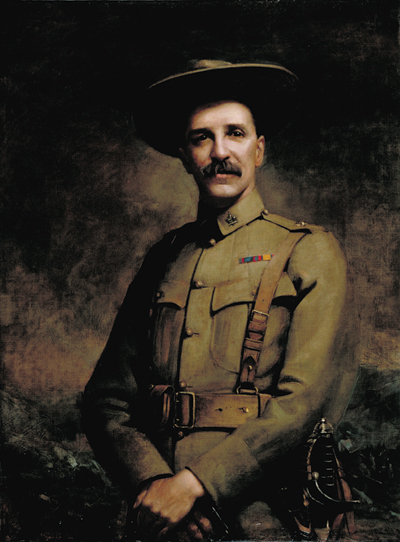

By late 1899 Gat Howard was a wealthy 54-year-old widower, second wife Margaret having died during childbirth in 1897. Howard’s business concerns were quite profitable, he was a 32nd degree Mason and a leading citizen of Brownsburg. But there was a war on in South Africa, and Howard wanted in on the action. At a time in life when many men look forward to retirement, Howard was willingly off to combat.

He reportedly offered to raise, equip and command a machine gun section for the 2nd Contingent, but the government declined his offer. Instead, it commissioned him a lieutenant and gave him a rather open assignment. A newspaper of the time summed it up: “Howard is not to be attached…to any particular division or company but is to be something of a freelance…in charge of the Maxim machine guns.”

Howard set sail for South Africa from Halifax in January 1900. On arrival he commanded the machine gun section of the Royal Canadian Dragoons, which was equipped with one Model 1898 .30-caliber belt-fed Colt machine gun and one bulky, unreliable Maxim.

Joining a large British force in its advance on the Boer capital of Pretoria, the Canadian dragoons busied themselves with reconnaissance, flank protection, intelligence gathering and other scouting duties. Many in the column believed the Boers’ will to fight would crumble when Pretoria fell on June 5, but the Afrikaners were determined to continue their guerrilla war against British forces.

After the fall of the Boer capital, the dragoons manned outposts, protected rail lines and battled enemy commandos into early autumn. During one seek-and-destroy operation Howard deployed far forward with the Colt machine gun, risking capture or death. Bearing the hot-barreled weapon in his arms, he narrowly escaped encirclement by the retreating Boers, earning a stiff reprimand—and likely grudging respect—from the regimental commander for his bravado.

In his memoir With the Guns in South Africa Sir Edward W.B. Morrison, who during the war was a lieutenant in the regimental horse artillery, offered the following description of Howard:

“Gat” Howard has become almost as conspicuous a figure in the British army of South Africa as he was in the Northwest field force. He deservedly bears the reputation of being one of the bravest men in the army and, his critics add, one of the most reckless. Yet there would appear to be a method in his madness, because though he has been in many tight places, he has not lost many men.…He is blessed with a positive optimism that makes him think he is always right.…For a man of his years and physique he is a marvel of energy and endurance, and everybody likes “Gat.”

On Nov. 7, 1900, while Howard was on leave in Pretoria, Sergeant Edward J.G. Holland of his section earned the Victoria Cross for using the Colt machine gun to repel a Boer attack on an artillery battery. Morrison, an eyewitness to the action, noted, “It is a good thing that ‘Gat’ Howard was not out with it, or there likely would have been one more casualty on our side.”

At year’s end the Royal Canadian Dragoons prepared to return home, but Howard wasn’t going with them. British army commander Lt. Gen. Lord Herbert Kitchener hoped to raise irregular mounted units to defeat the Boers using their own unconventional tactics, and newly promoted Major Howard was authorized to recruit a 125-man force.

In January 1901 the Canadian Scouts (aka “Howard’s Scouts”) mustered for duty. Most of the troopers were Canadians who had served in mounted units, like Howard’s second-in-command Captain Charlie Ross, who was also a U.S. Cavalry veteran. Although all 114 of the original members of the Canadian Scouts were given the rank of sergeant, not all recruits were suited to be noncommissioned officers, particularly those who had signed on from the docks of Cape Town.

The scouts were organized into two troops of 30 men each and one 24-man machine gun section. Howard asserted his influence and expertise, equipping the unit with six Colt machine guns—three times the firepower allocated to a typical regiment.

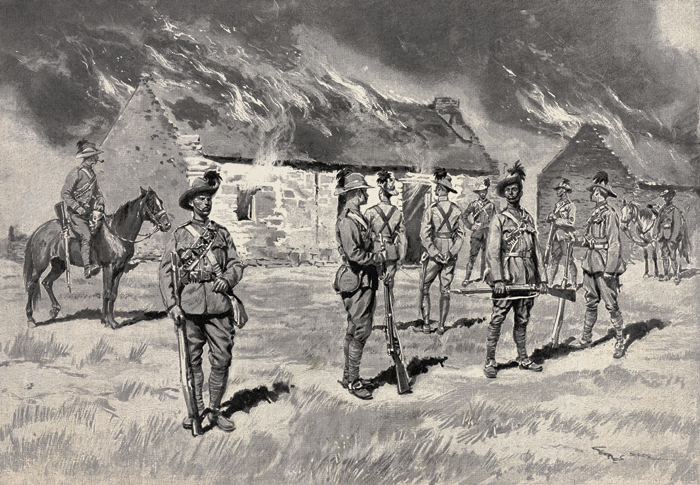

Shortly after mustering into service the scouts were assigned to a large British force charged with Kitchener’s “scorched earth” mission to eliminate Boer resistance. Two scouts were killed and one of the machine guns fell into Boer hands on Jan. 27, 1901. Although the scouts did engage in firefights with Boer commandos, most of their time was spent evicting families and burning farms in the effort to deprive Boer forces of logistical support. “We get so many sheep,” Ross reported, “that we have to kill hundreds every day and burn every wagon, buggy, saddle, etc., we don’t require for our own use. We are leaving an awful trail of smoke and ruin wherever we go.”

Unsubstantiated reports claimed the Canadian Scouts adhered to an unofficial policy of executing Boer prisoners, which would certainly not be unusual given the brutal nature of that phase of the war. It is also probable the Boer commandoes held Howard’s scouts in particular contempt, given their operations to destroy farms and displace civilians.

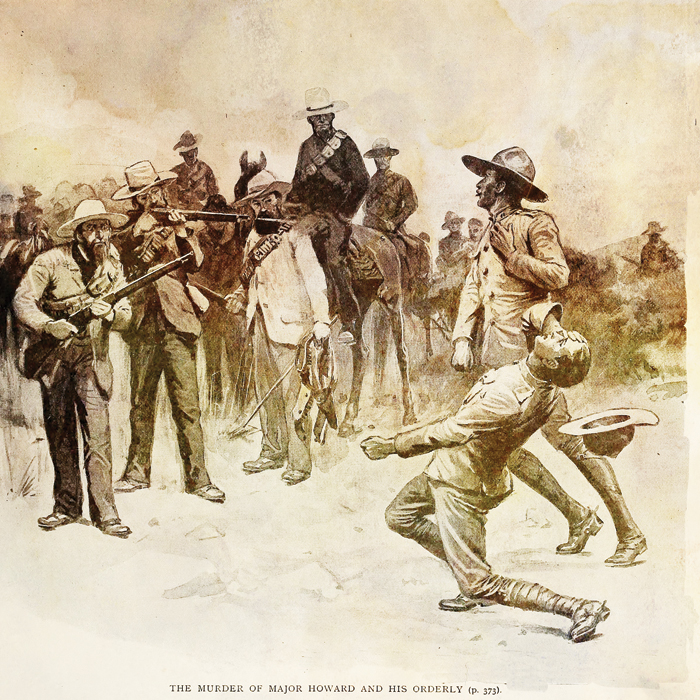

On Feb. 17, 1901, while patrolling for Boer commandos, Howard, Sergeant Richard Northway and a native scout spotted a cluster of wagons in a valley. Riding to investigate, the party came under fire from concealed Boers. The trio sought cover amid the wagons, but the Boers closed in, cutting them off. On hearing the distant gunfire, the remaining scouts charged in to rescue their commander. They arrived in the valley to find Howard’s lifeless body, with the other two men lying beside him severely wounded.

‘Major A.L. Howard (killed) has been repeatedly brought to my notice for acts of gallantry,’ Lord Kitchener noted

Reports vary regarding the specifics of Howard’s death. All concur he was shot in the arm, jaw and stomach. Some allege Howard had handed over his weapons and surrendered to the Boers, who had then executed the commander of the hated Canadian Scouts. Other reports suggest Howard fell during the initial firefight with the Boers. Still another claims the Boers shot Howard after he’d refused to hand over his Masonic ring.

Lord Kitchener noted in his March 8 dispatch, “Major A.L. Howard (killed) has been repeatedly brought to my notice for acts of gallantry.” The American-born major was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Order for his heroic service in South Africa.

So ended the remarkable life and career of Major Arthur “Gat” Howard, DSO—U.S. cavalry trooper, Connecticut National Guardsman, Royal Canadian Dragoon and commander of the Canadian Scouts. Born in a small New England village, he became a valiant warrior and Canadian patriot who gave his life for the British empire.

P.G. Smith is a retired U.S. Army brigadier general who has written several articles for Military History. He is a visiting instructor at the U.S. Army War College and teaches counterterrorism strategy at Nichols College. For further reading he recommends Knowing No Fear: The Canadian Scouts in South Africa, 1900–1902, by Jim Wallace with Captain Michael Dorosz, and The Battle of Batoche: British Small Warfare and the Entrenched Métis, by Walter Hildebrandt.