Abraham Lincoln was arguably the most merciful man ever to occupy the White House. In his first year as president, he had already earned a reputation for the liberal use of the power to pardon. And while some saw him as a compassionate, merciful man, others—including members of his own Cabinet—considered him a sentimental meddler who constantly undermined the discipline and sanctity of the courts, both civilian and military. As Attorney General Edward Bates confided to his diary, Lincoln “was unfit to be entrusted with the pardoning power because he was almost certain to be affected by a touching story.”

Lincoln’s generals were constantly flummoxed by his refusal to see boys shot for sleeping on picket duty or running from the terrors of battle. General Joseph Hooker once sent the president a sealed envelope containing the cases of 55 convicted and doomed deserters; Lincoln merely wrote “Pardoned” on the envelope and returned it to Hooker unopened. Lincoln’s mercy extended to the warring South; he declared himself “ready at any time to grant a general amnesty with a remission of all penalties except the loss of property in slaves, if the measure would hasten the return of peace….”

And yet, this kind and forgiving man, whose clemency went beyond all reasonable expectation, was responsible for the largest mass execution in our nation’s history.

The history of our government’s relations with the Indians is disgraceful. In Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, Dee Brown points out that Congress never made a treaty it wasn’t more than willing to break. Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, tribe after tribe was left with no recourse other than rebellion or starvation. And the Dakota Sioux were no exception. Ten years before the Civil War, the United States signed two treaties with the Sioux that resulted in the Indians giving up huge portions of Minnesota. In exchange, they were promised compensation in cash and trade goods and were directed to live on a reservation along the upper Minnesota River.

The thoroughly corrupt Bureau of Indian Affairs was responsible for overseeing the terms of the treaties—something akin to entrusting sheep to a pack of wolves. Not surprisingly, many of the trade goods were substandard and overvalued by several hundred percent, and the promised payments were often stolen by Washington functionaries, never sent, or simply given directly to the crooked traders and Indian agents.

Finally, in 1858—the year Minnesota entered the Union—a party of Sioux led by Chief Little Crow visited Washington to see about proper enforcement of the treaties. But instead of acknowledging the Sioux grievances, the U.S. government took back half their reservation and opened it up to white settlement. The land was cleared, and the hunting and fishing that had in large measure sustained the Sioux virtually ended. With each passing year, the Sioux suffered increasing hunger and hardship. There was nothing to be gained by appealing to the traders; according to tradition, their representative—a clod of a fellow named Andrew Jackson Myrick—responded to the Indians’ appeal for food by saying, “So far as I am concerned, if they are hungry, let them eat grass or their own dung.”

In August 1862, the powder keg exploded. It began almost randomly, when a party of four braves on an egg-stealing foray impulsively killed five white settlers. From there, it escalated rapidly. Under the leadership of a somewhat reluctant Little Crow, and with the support of such chiefs as Shakopee, Mankato and Big Eagle, several bands held a war council and set about attacking the new settlements. They seized the Lower Sioux Agency, killing whites and burning the buildings.

In response, a combined force of militia and a company of the 5th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry was sent to subdue the Indians; the parties met at Redwood Ferry, where the Indians gave the soldiers a thorough drubbing: 24 of the soldiers died and commanding officer John S. Marsh drowned in retreat. Flush with victory, roving bands of Sioux destroyed entire townships, plundering and killing as they went. They attacked stagecoaches, relay stations and couriers as hundreds of panicked settlers fled to army posts. A.J. Myrick was one of the first victims. When his body was discovered, his mouth was stuffed with grass.

A number of desperate appeals for help had gone to Lincoln, but he was preoccupied with Second Bull Run, Robert E. Lee’s invasion of Maryland and the release of the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.

Finally, more than a month after the outbreak of the Sioux uprising, President Lincoln assigned Maj. Gen. John Pope, fresh from his defeat at Second Bull Run, the task of ending the uprising. Pope declared his “purpose to utterly exterminate the Sioux….” He commanded elements of the 3rd and 4th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry; along with troops from the 6th and 7th Minnesota, armed with a 6-pounder and buoyed by companies of “civilian soldiers.” The army finally subdued the Sioux on September 23 in the Battle of Wood Lake. Those who surrendered were promised safety. The butcher’s bill at the end of hostilities totaled some 77 soldiers killed, around 75 to 100 Sioux, and—no one took an accurate count—between 300 and 800 settlers.

Hundreds of Sioux were arrested—some of whom had had nothing to do with the uprising—and summarily tried by a five-man military commission. The trials were perfunctory affairs, some lasting less than five minutes. More than 40 cases were adjudicated in one day alone. If any defendant admitted to so much as firing a gun, he was condemned.

Of the 393 tried for “murder and other outrages,” 323 were convicted, and 303 sentenced to hang—including those who had surrendered with a promise of safety.

The final approval for the executions rested with the president. General Pope pressured Lincoln to sign the orders for all 303 executions. Outraged newspaper editors and congressmen also advocated a speedy hanging. The governor of Minnesota—who had made a fortune cheating the Sioux—threatened that if the president didn’t hang all the condemned, the citizens of his state would.

The Sioux had a rare friend, however, in Minnesota’s Episcopal bishop, Henry Whipple. The clergyman traveled to Washington and met with Lincoln, who was so impressed with Whipple’s account of corruption and abuse that he resolved to reform the Indian situation in government. Sadly, he would fail.

He did, however, order that every case be examined on its own merits. After thorough analysis, only 39 Sioux could be proved to have participated in the uprising. Lincoln immediately approved their execution order, and commuted the sentences of the others. He would eventually spare one more. The president hand-wrote the list of long, difficult, phonetically spelled Sioux names himself and advised the telegrapher on the vital necessity of sending them correctly, lest the wrong men be hanged.

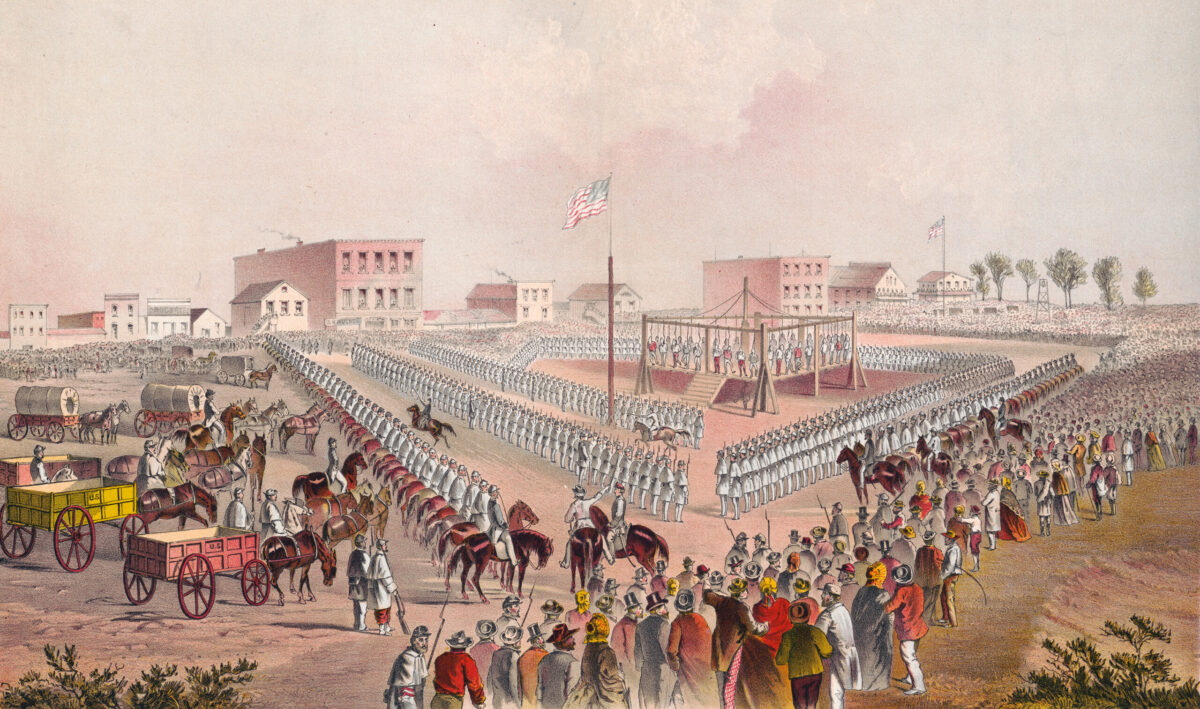

On December 26, 38 Dakota Sioux were led to the scaffold; they sang their death songs as they walked, and when they had mounted the scaffold and the hoods were drawn over their faces, they continued to sing and sway and clasp each others’ manacled hands. At a drum signal, the trap was sprung and the watching crowd of thousands cheered.

The Sioux were buried in a mass grave, but were exhumed shortly thereafter and distributed among a number of doctors for study. Some of the dead were reportedly flayed, and small novelty boxes made from their skin sold in Mankato.

Those whose sentences had been commuted were sent to prison for four years, where a third of them died. Some 1,600 Sioux women, children and old men were placed in an internment camp, where cold, hunger and disease killed more than 300.

The year after the uprising, Congress expunged all Sioux treaties from the record, took back their reservation and ordered the entire tribe expelled from Minnesota; as an incentive, a bounty of $25 was offered for the scalp of any living Sioux found after the edict. The reluctant warrior Little Crow, who had escaped to Canada after the Indian defeat, came back to Minnesota—and was shot from ambush while berry picking with his son on July 3, 1863. His killer was given an additional $500 reward, and the chief’s skull and scalp were sent to St. Paul, where they remained on display until 1971. There was still scattered resistance, but the Dakota War was over. The Sioux would continue to fight until 1890, when the U.S. Army marked paid to their account at Wounded Knee.

Given the mood of the country regarding what were seen as unprovoked savage depredations, what drove Lincoln to spare the lives of so many Sioux? Lincoln was, indeed, a man of mercy; but he was no soft touch. If he perceived that a man needed to be hanged, Lincoln allowed the law to run its course. And kind though he was, he was still very much a product of his time and a firm believer in the right to a westward expansion limited only by the edge of the sea.

Lincoln defended Andrew Jackson’s policy of Indian removal, and in an 1863 address to a delegation of visiting chiefs, Lincoln advised them that the only route to their survival lay in taking up farming and had the temerity to lecture the chiefs on violence: “Although we are now engaged in a great war between one another, we are not, as a race, so much disposed to fight and kill one another as our red brethren.”

The wonder isn’t that Lincoln allowed more than three dozen men to hang; it’s that he took the time away from a war that was going badly to examine one at a time the cases of more than 300 Sioux, and to spare the lives of all but 38. While Lincoln felt the wholesale killing of settlers could neither be condoned nor ignored, he would not allow the law to be used to elicit indiscriminate revenge, despite tremendous pressure. When it was suggested that he would have garnered political support by allowing the original orders to stand, he responded that he “could not hang men for votes.” Selectively allowing the executions of the 38 men was to Lincoln an act of justice, tempered with his characteristic mercy.

Ron Soodalter is the author of Hanging Captain Gordon: The Life and Trial of an American Slave Trader.

Originally published in the July 2009 issue of America’s Civil War.