The sea and its creatures were of course familiar subjects for most Rhode Island soldiers.

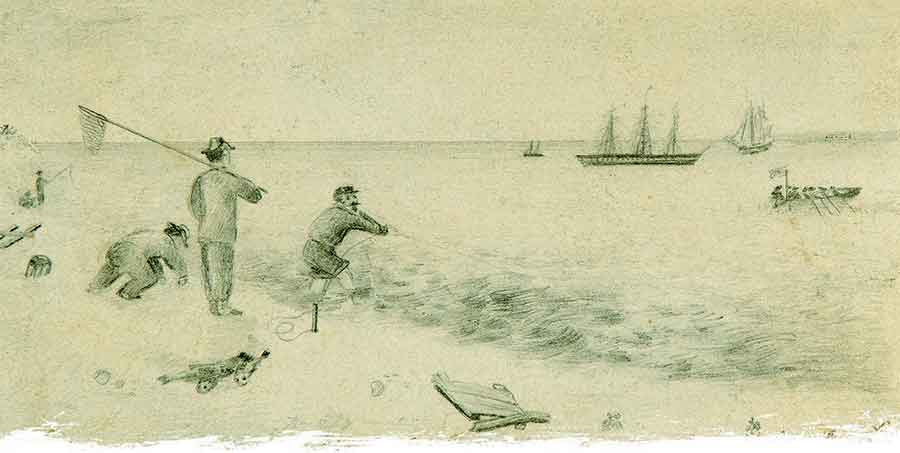

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]t wasn’t surprising, therefore, that the Ocean State boys of the 2nd Rhode Island Cavalry chose to pass the time with a little “fishing” as they sailed through the Gulf of Mexico to New Orleans in the summer of 1863. Captain William Stevens, of Company C, recalled that his fellow troopers decided to alleviate their boredom during the voyage by tying chunks of meat to strings and throwing the lines over the side of their transport ship, hoping to entice sharks to bite and perhaps grab on for a ride. For the accidental sport fisherman, the pastime would prove unsuccessful. Stevens, however, couldn’t help lament that several of the regiment’s horses had died during the voyage and were thrown overboard. The unfortunate beasts, he noted, provided a veritable “feast” for the finned predators who then had little appetite for the offered bait.

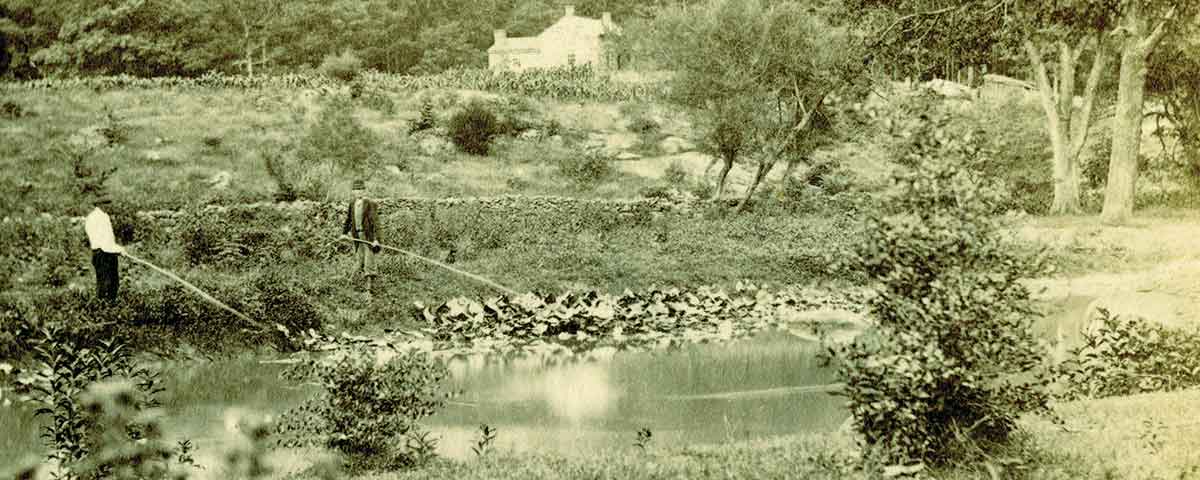

While Stevens and his comrades, attached to the 19th Corps in the Department of the Gulf, tempted fate with sharks to break the boredom, other soldiers during the war would fish to supplement sometimes meager and unappetizing rations, and it was a common activity among troops in both armies. They did so in camp and on the march by using a variety of ad hoc fishing devices. One soldier advocated the

use of a “light tapered pole” or stick on which the line would be tied. Another improvised and used a thin piece of wood shaped like an “hour glass,” about 4- by 1½-inches in size, to make a handfishing tool. A slight concave at both ends allowed the hook and line to be wrapped for carrying. If one of these could not be had, a small stick made a suitable substitute. All the soldier had to do was obtain a hook, some kind of fishing line and bait, and the battle for a wily trout, catfish, or other edible species would begin.

Hooks came in various sizes depending on the type or size of fish desired. Small hooks about a half-inch long were used for trout and other small fish, with larger hooks up to 3 inches long for large freshwater game fish and those of the saltwater variety. Made from a piece of curved stiff wire, one end would be flattened or stamped into a “spade” shape, where the line was tied, and the other end contained a barbed sharpened tip.

Confederate Lieutenant Frank Robertson of Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart’s staff would write home to his wife requesting fishing hooks and lines, if she could find them. In one letter, he drew the specific sizes of hooks he needed that could be used for trout, sunfish, and small catfish. On the Gettysburg battlefield, along Willoughby Run, one enterprising soldier left behind a bent sewing needle used for a hook along with other angling items.

Store-bought fishing lines of the era varied. Typical manufactured lines were made from braided horsehair, braided silk, or a combination of both, which was preferable and more durable. Soldiers in the field would sometimes substitute heavy thread or small cord in case regular line was not available. Commercial floats or “bobbers,” were also available and could be made from any piece of wood, cork, or even sections of dried corncob. The float was then tied on the line above the hook, the distance depending on the depth of the water. Sinkers or weights to send the bait to the bottom and for ease of casting into a stream or body of water were sometimes fashioned by splitting open Minié balls or other lead bullets. Once the bullet was separated, it could be crimped around the line at the desired spot.

Northern soldiers in the field had better access to manufactured fishing items than their Southern counterparts. Newspapers published in the North between 1862 and 1865 ran numerous fishing advertisements, while Southern newspaper ads for fishing tackle during that period were virtually nonexistent. Southern papers, in fact, would not have advertisements for tackle again until after the war.

Bait mostly came in the form of worms or sometimes, according to Lieutenant John Blue of the 17th Virginia Cavalry, “crickets and bugs” were used to tempt fish. Blue had been part of a mountain company near his home of Romney in western Virginia early in the war and described how he and fellow soldiers fished in mountain streams to supplement their rations. Later in the war, they would cast lines into the headwaters of the Gauley River in Greenbrier County for “trout of which the mountain streams seemed to be alive.”

Other soldiers would substitute whatever was readily available to them. In The National Tribune, a newspaper dedicated to soldier submissions after the war, a story featured fictional Private Si Klegg of Company Q, 97th Illinois, who participated in William T. Sherman’s 1864 March to the Sea. Klegg described how he saw a member of his company using “just a hook and line and a piece of pork for bait” to go after catfish. Even though this was a fictional account, Klegg’s adventures were based on actual events.

Fishing in Wartime

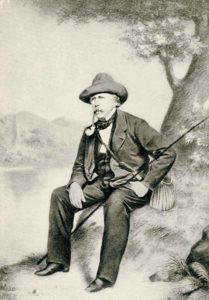

Thaddeus Norris published The American Anglers Book in 1864. Though the book was probably not part of a typical Northern or Southern soldier’s reading material, Anglers Book was an indication of how fishing was taking hold as a recreational pursuit for a larger segment of the American population, even as the Civil War continued to grind on. Norris offered advice on how to build and use fishing tackle as well as what techniques were needed to catch both fresh- and saltwater fish. The work even explained the art of fish breeding to the common angler. Norris would further explain that the everyday angler needed a rod, preferably 12 feet in length, the handle made from ash with a hickory, bamboo, or lancewood rod tapered to a metal ring tip with loose ring “eyelets” spaced along its length. Fitted with a metal reel, produced by William Billinghurst or several other American and foreign makers, the rod could be broken down into two pieces. –B.E.S.

Other soldiers also wrote about their attempts and successes while fishing and eating what they caught. While encamped near Beverly, W.Va., along Seneca Creek—known for its abundant population of trout—the 10th West Virginia’s 13-year-old drummer Ransom T. Powell described how he and his comrades did their “best towards depopulating it.” While stationed in Alexandria, Va., J.E. Cutler of the 29th Maine Infantry would write of a huge catfish caught by one of his comrades in the Potomac River that had to be “shared with a friend from the 29th Wisconsin.” The Maine boys, however, were ordered on picket duty, so Cutler and his messmates were unable to sample the fresh catch.

On February 5, 1863, Private Edward O. Austin of the 171st Pennsylvania Militia, writing from the New Bern, N.C., area to his hometown newspaper the Potter Journal, cited the “warm weather” and how “The men are occasionally fishing in the river catching eels and catfish.”

Catfish, trout, and eels were not the only types of fish soldiers would catch. Other species of fish and water-dwelling creatures would be sought after for both sport and food. E.B. Lufkin of the 13th Maine wrote after the war of being stationed near Lake Pontchartrain in New Orleans and watching fellow company member Jerry Osgood catching a “garfish” more than 5 feet long. Lufkin described the fish as being shaped “much like a pickerel and mottled in the same way but of a different color.” He went on to explain that he and his cohorts were afraid to bathe in the lake as the gar were said to grow 10–12 feet in length, making them more feared than even the local alligators. Corporal Charles Wasage of the 47th New York Infantry recalled that when his unit was stationed on Ossabaw Island at the mouth of the Ogeechee River in Georgia, the men would catch and eat sea turtles that “answered us for fresh beef.”

Alfred Wilson and Mark Wood of the 21st Ohio, two of the raiders who hijacked the Confederate locomotive General during the Great Locomotive Chase in April 1862, experienced similar good fortune. The two were captured in the raid and sent to a Rebel prison near Chattanooga, Tenn. They were able to escape and commandeer a small boat, however, and set out along the Chattahoochee River, intending to follow it to Columbus, Ga., where Union ships would hopefully be waiting.

After several weeks of subsisting on pumpkin, roots, and raw corn, they came upon some fishing hooks and lines in an empty cabin. Soon they were eating raw catfish, which Wilson described as “palatable.” The escapees eventually reached Columbus where they met up with the Union fleet, but the experience had left both unfit for service. Wilson later said that the acquisition of the fishing paraphernalia had saved his and his partner’s lives.

But fishing for pure survival was the exception to the rule. Most of the soldiers, blue and gray, who baited a hook did so as a way to pass spare time and add variety to their diets. And, as they intently watched their bobbers, fishing helped them take their mind off war’s hardships and kindle memories of quieter days at the town pond or along the stream that ran through their family farm.

Fly Reels and Rapid Fire

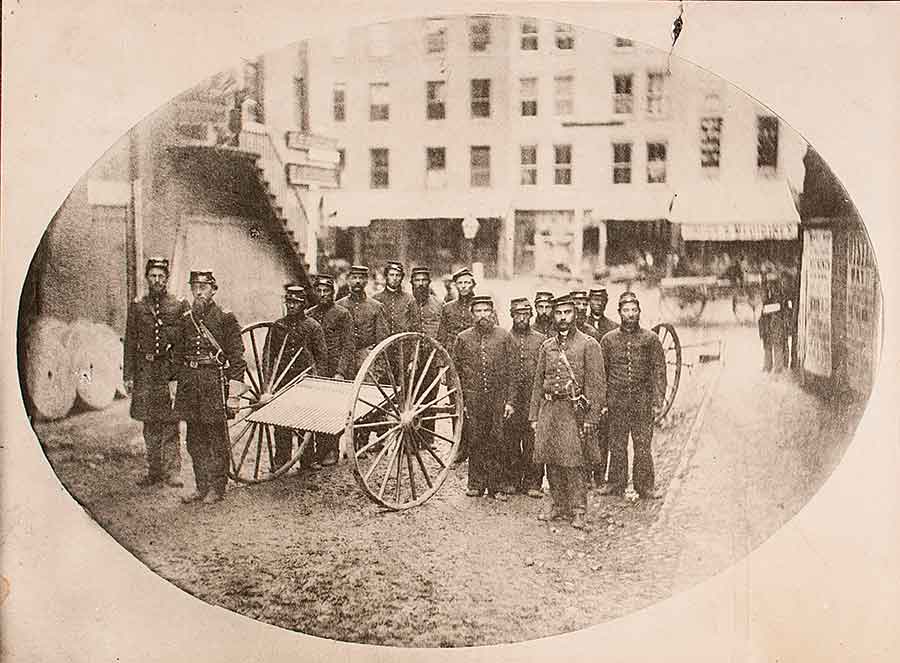

In 1859, William Billinghurst manufactured what many to consider to be the first American-patented flyfishing reel. The brass reels were designed to mount on the sides of their rods and were delicate and light to provide the balance needed when precisely casting a small fly lure into a quick-moving trout stream. The Rochester, N.Y., native’s main talent, however, was gunsmithing, and he was particularly adept at producing repeating rifles.

In 1861, he teamed with former apprentice Josephus Requa to make one of the first practical machine guns, the Billinghurst-Requa Volley Gun. The weapon consisted of 25 breechloading barrels, which used specialized brass cartridges that could be fired by a single percussion cap. The inventors claimed the .52-caliber barrels, mounted side by side, could spew out up to 175 shots per minute. Billinghurst demonstrated the gun for President Lincoln and was granted a patent for the weapon on September 16, 1862. He was unable, however, to reel in a coveted federal contract during the Civil War for his invention.

Approximately 50 volley guns were still produced for about $500 each, and some were deployed by Federal troops against Fort Wagner during the siege of Charleston, S.C. A few Army of the James’ batteries used them in the trenches outside of Richmond and Petersburg in 1864. –D.B.S.

Brian E. Stamm, a retired corrections officer based in Bellefonte, Pa., is currently researching the 2nd Pennsylvania Cavalry.