Grumman’s F6F Hellcat was perfectly suited to young American naval aviators battling Zeros in the Pacific.

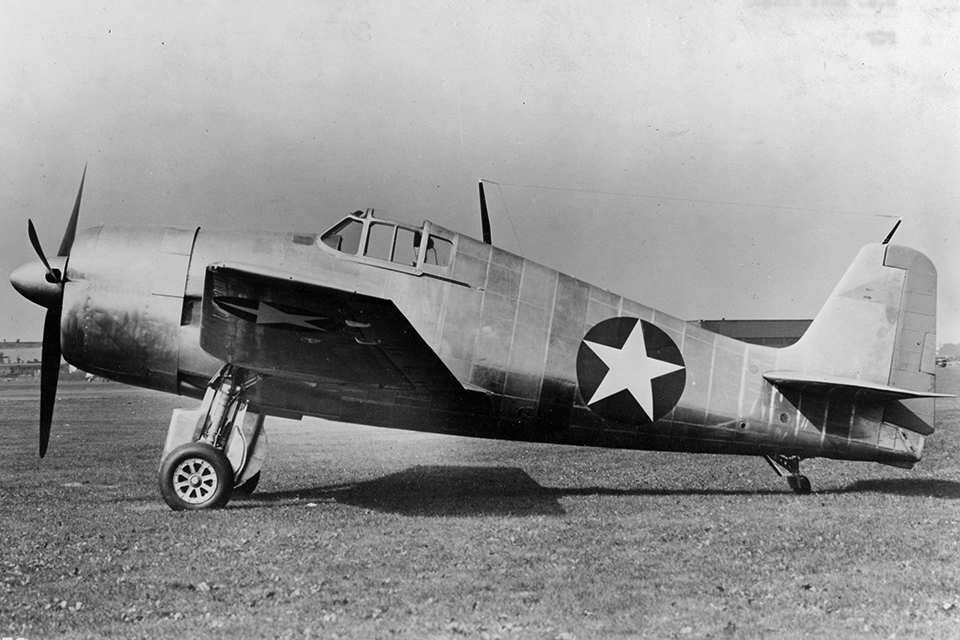

Rarely has there been a combat aircraft so perfect for its time and place as the Hellcat. “No more outstanding example of skill and luck joining forces to produce just the right aeroplane is to be found than that provided by the Grumman Hellcat,” wrote legendary British test pilot Eric “Winkle” Brown in his book Wings of the Navy. This bluff, sensible, utterly workmanlike shipboard fighter arrived in the Pacific theater in August 1943 and went to work straight out of the box. The Hellcat immediately challenged what had been the most powerful naval air arm on the planet and beat it like a bongo, racking up by far the highest kill-versus-loss ratio of any airplane in American service during World War II (19-to-1, based on claimed shootdowns). It resoundingly won the most one-sided, humiliating air battle of any war—the Marianas Turkey Shoot. Unlike other fighters that went through lengthy series of engine, airframe and armament changes, the F6F was hardly modified or updated thereafter, and there were only two basic versions of the airplane during its entire lifetime: the F6F-3 and -5.

The Hellcat’s initial development proceeded virtually without incident. The fighter proved to be as tough, reliable and durable as a Peterbilt. It was viceless and turned out to be the ideal airplane for young, inexperienced ensigns to operate from aircraft carriers. Grumman claimed it had been “designed to be flown by 200-hour farmboys.” In combat for just under two years, the Hellcat was as unbeatable on the day it stood down as it had been when it arrived for its very first mission.

Yet despite—or perhaps because of—such a straightforward, matter-of-fact career, the F6F got far less respect and fandom than did its more stylish rival, the Vought F4U Corsair. The Corsair was an arrogant, long-nosed Shelby Cobra; the Hellcat was a looming Ford F350 dualie pickup. The Hellcat flew in combat for 24 months and then essentially disappeared, never to fight again (other than an odd Korean War experiment and a few minor missions for the French over Indochina). The name of the top Hellcat ace, David McCampbell, is far less familiar than those of Dick Bong, Gabby Gabreski, Pappy Boyington and other pilots of more glamorous fighter types. No Hellcat ever Reno-raced or starred in a TV series. No Hellcat ever had the panache of a Sea Fury, a Hose-Nose, a Tigercat or Bearcat. Three Hellcats (with a fourth as spare) lasted just two months as the first Blue Angels team aircraft before being tossed aside in favor of Bearcats. Oh, the ignominy…

The Hellcat began life as a proposal that Grumman build a “Wilder Wildcat.” Clean up the dumpy F4F airframe, add some firepower, get rid of the hand-cranked 1930s landing gear and slap on a bigger engine. Then came reports first from actual air combat over France and Britain, and then input from U.S. Navy and Marine pilots who had flown against the Japanese. Grumman engineer Jake Swirbul flew to Hawaii in 1942, soon after the Battle of Midway, and had a sit-down with Commander John S. “Jimmy” Thach, the Wildcat ace who developed the famous Thach Weave defensive maneuver.

Grumman had already decided that the need for armor plate, additional guns, greater range and a big ammo and fuel load meant they had to deliver more than just a Super Wildcat; after all, the F4F was a mid-1930s design that came close to being built as a biplane. Thach and other pilots told Swirbul they needed a more powerful engine than the 1,700-hp Wright R-2600 with which the prototype XF6F-1 had been fitted. The obvious answer was Pratt & Whitney’s magnificent new 2,000-hp R-2800. A turbocharged R-2800 was mounted on the prototype, which became the XF6F-2, followed by the XF6F-3 with a two-stage supercharged version, and Grumman never looked back.

The myth persists that the move to the R-2800 resulted from flight tests of the famous “Akutan Zero,” the intact Mitsubishi A6M2 salvaged from the Aleutians, but it’s not true. The first flight of the production version of the F6F, in October 1942, took place just two weeks after flight-testing of the Akutan Zero began in San Diego. It’s laughable to think that the Navy flew the Zero and instantly decided the F6F needed a bigger engine, acquired the still-rare Pratt & Whitney, had Grumman rework the Hellcat airframe to carry it and then created a production version all within two weeks. The Akutan Zero affected Hellcat air combat tactics, but had nothing to do with its development.

More than a thousand F6Fs had been built before the airplane got a name. It was generally referred to in Bethpage during that time as the Super Wildcat. “Tomcat” had been considered, but in the mid-1940s that was considered a bit too risqué. It would take a couple of generations before the concept of a randy animal was considered appropriate. Roy Grumman himself chose the name Hellcat, so profanity trumped sexuality.

The Hellcat’s strength, literally, was its simple and straightforward design. In those days, Grumman’s credo was “Make it strong, make it work and make it simple.” The prototype XF6F-3 became the production F6F-3 nearly untouched, and the only other Hellcat upgrade, the F6F-5, mounted an R-2800-10W that had an additional 200 hp. There were night-fighter, photoreconnaissance and export variants, but the basic airframe and engine remained untouched throughout the Hellcat’s combat career.

A Hellcat can be drawn with a ruler. Its big wings are simple geometry-class trapezoids, and its fuselage and empennage are all straight lines. The Hellcat’s wings are the largest of any WWII single-engine fighter, Allied or Axis, and it’s often overlooked that the F6F was a huge airplane. The P-47 was larger, but only by inches. The substantial wing area and consequent low wing loading made comparatively slow carrier approach speeds possible—5 mph slower than a Wildcat, in fact—and rendered the Hellcat at least adequately maneuverable for such a big airplane.

Armchair aviators often make too much of the importance of maneuverability for a fighter during WWII. Royal Navy test pilot Winkle Brown rates the important elements of a fighter, in descending order, as speed, climb rate, firepower, armor protection, pilot visibility and—last of all—maneuverability. What he means is that if you have the speed and rate of climb to choose when and where to initiate or break off combat, maneuverability can be nullified by two words: “Don’t dogfight.”

In fact, if the Hellcat had a flaw, it was excessive longitudinal stability, at least initially. The big bird didn’t want to turn. The F6F-3’s ailerons were unpleasantly heavy and ineffectual at high speeds, though the addition of aileron spring tabs to the F6F-5 cured this affliction. (Spring tabs are a kind of automatic trim tab. As an aileron is deflected down, a small control surface on that aileron’s trailing edge is deflected up, and that movement into the relative wind boosts the aileron’s downward movement. The reverse happens on the up aileron.)

The big wing’s ample wetted area also kept the Hellcat comparatively slow. The 386-mph maximum speed of even the late-model F6F-5 was far below the F4U-4 Corsair’s 452 mph, and the P-38L, P-47D and P-51D all had top speeds well into the mid-400s. But the Hellcat’s main opponent was the 331-mph Zero, so this wasn’t much of a problem.

It’s worth noting, however, that while the F6F’s claimed shoot-down ratio over the Zero was 13-to-1, it scored a less impressive 3.7-to-1 against the Zero’s successor, the 1,820-hp Mitsubishi J2M Raiden. Flown by pilots of equal skill, the two would have been closely matched.

Many aren’t aware that Hellcats also served in the European theater. Both U.S. Navy and British Fleet Air Arm Hellcats flew ground-attack missions during the August 1944 invasion of southern France, a campaign largely forgotten because all eyes were on the far more spectacular breakout from the Normandy beachhead. Carrier-launched FAA Hellcats also flew top cover for a major bombing mission against the battleship Tirpitz on April 3, 1944, when the German supership was preparing to venture out of its Norwegian fjord. British Hellcats supposedly tangled with Luftwaffe Me-109Gs and Fw-190As on May 5, 1944, but after-action reports were typically confused. The Luftwaffe claimed three Hellcats downed for the loss of three Messerschmitts, while the British claimed two F6Fs lost in what might have been a midair collision. The combats were brief and inconsequential, though Hellcats did shoot down several German bombers over France.

A Messerschmitt or Focke-Wulf versus Grumman air battle would have been an unfair fight in any case. A WWII carrier-based airplane was a collection of compromises. It was designed to live and be serviced aboard a ship and to use an 800-foot runway—or 500 feet in the case of escort carriers. With folding wings, a tailhook, heavy landing gear and design features optimized for survival over vast ocean distances, an F6F probably would have been no match for a well-flown Fw-190.

The Navy’s carrier-borne fighter was the Hellcat, and that was it. In June 1944, Task Force 58, in the Philippine Sea, had 450 fighters, all Hellcats. At the October 1944 Battle of Leyte Gulf, Task Force 38 had nearly 550 fighters, and every last one was a Hellcat. Such complete standardization made servicing, arming, maintaining and flying the airplane as easy and seamless as possible.

Corsair enthusiasts will of course protest that their favorite Navy fighter was demonstrably the better airplane. Judging by sheer performance numbers, that’s true. The F4U was substantially faster and had a better rate of climb, range and ceiling than the F6F, and of course it went on to do yeoman work in the Korean War while the only Hellcats still flying were advanced trainers and drones. But the Corsair went through a lengthy and troubled development period and ultimately turned out to be a difficult-to-manage carrier plane with some unfortunate stall characteristics (the reason the original Blue Angels chose the F6F over the F4U).

In truth, the two airplanes represented two quite different approaches to the challenge of developing a Navy fighter. The Corsair sacrificed cost and certain handling qualities—notably the ability to approach and land successfully on a carrier—in exchange for maximum performance, while the Hellcat was designed to provide economy and manufacturability plus good performance and competent carrier-deck handling. The Corsair was unforgiving to fly, the Hellcat was easy. This was not a trivial consideration at a time when the Navy was welcoming aboard thousands of new young ensigns.

Grumman cranked out so many F6Fs that the Navy had to ask the company to slow down. At one point a rumor circulated that Grumman was going to lay off workers because they didn’t need to build so many Hellcats. So the entire factory crew worked harder than ever, each employee trying to prove that he or she didn’t deserve to be cut, and the awkward result was another new monthly production record.

Grumman built 12,275 Hellcats in just 30 months. That’s better than 16 airplanes a day for a six-day workweek. At the height of production, Grumman was turning out a Hellcat every hour, a record that has never been equaled. Hellcats were also a bit of a bargain: Despite their near-identical engines, the Navy could buy five F6Fs for the price of three F4Us. In 1944 and ’45, the Japanese faced 14 enormous Essex-class carriers plus 70 light and escort carriers, all of them packed tight from hangar deck to flight deck with Hellcats, endless Hellcats, flown by superbly trained, combat-experienced…well, maybe they were farmboys, but they’d grown up handling John Deere combines and driving Dad’s ’36 Ford.

Grumman had no media-star designer, no Kelly Johnson, Ed Heinemann or Alexander de Seversky. Leroy Grumman himself, an ex-Navy pilot and MIT graduate, did the brilliant conceptual work on the Hellcat. His partner William Schwendler refined it, and much of the real engineering was done by Richard Hutton, widely admired in the industry but hardly a household name. The third founding partner of the company, Leon “Jake” Swirbul, was a manufacturing and production specialist with a remarkable ability to keep the workforce so devoted that Grumman had the lowest personnel turnover rate of any WWII airframer.

Unlike many other aeronautical engineers, Roy Grumman was a Pensacola-trained pilot, and he stayed current by flying the company hack, a civil version of Grumman’s short-coupled and demanding F3F biplane fighter. During the Hellcat’s heyday Grumman, then 50, showed up at the production test pilots’ ready room one day and announced that the Old Man wanted to fly an F6F. Nobody was about to say no to the boss, so chief test pilot Connie Converse gave him a thorough cockpit checkout and then sent Roy out to terrorize the skies over Long Island.

He returned an hour later, proudly taxied up to the flight line and swung his Hellcat into its parking slot…with the flaps still full down, in their approach and landing position. Careful pilots consider this to be a no-no, because drooping flaps are vulnerable to damage from prop blast or stones thrown back by the wheels while taxiing. Grumman company pilots who committed this minor sin were required to stuff a dollar bill into a petty-cash jar. Somebody pointed out that this applied to the boss as well. Roy Grumman gave the jar $5, saying that should also cover the cock-ups nobody saw him commit while he was flying.

Apparently, no Republic or Chance Vought pilots, Grumman’s next-door and across-the-Sound neighbors, spotted Leroy during his F6F joyride. Grumman test pilots often had such a hard time getting their work done while being bounced by Thunderbolts and Corsairs over Long Island that the company took to painting TEST in large letters on the fuselage of F6Fs that were involved in serious flight-test programs. The four letters meant, “Go bother somebody else, we have work to do.”

Roy Grumman’s best-known contribution, originally designed for the F4F Wildcat but used nearly unchanged in the F6F, was the patented Sto-Wing folding system. Grumman came up with the concept of the skewed-axis pivoting joint that is at the heart of the wing-folding system by using two partially straightened paperclips stuck like wings into a rubber eraser “fuselage,” which is easier said than done. Grumman’s original eraser and paperclips survives to this day, embedded in a cube of Lucite atop a marble plinth in the main lobby of the Bethpage facility of what is now the Northrop Grumman Corporation.

It’s far easier to imitate an F6F’s folding wings by sticking your arms straight out to the sides. When the locking pins are hydraulically retracted, a Hellcat’s wings—your arms—fall down and arc back, nearly brushing the flight deck in their smooth swing. None of their motion is upward like conventional carrier airplane folding wings, and the weight of the wings provides nearly all the momentum needed to complete the fold. This meant two deck crewmen could handle the swing of a Hellcat wing and secure it in place.

Early in the design process, Grumman heard from Navy pilots how important good over-the-nose visibility was—one of the Corsair’s failings—so they simply jacked up the Hellcat’s cockpit and carried the forward fuselage and engine cowling up to it at an angle. This was a benefit during any kind of turning fight, when a pursuer might actually be shooting at a target that was slipping below his nose. If a tail-chasing pilot was pulling 5 or 6 Gs and trying to light up a hard-turning target, his machine-gun rounds were actually following a downward parabola. Not being able to see what they might or might not be hitting was a serious disadvantage.

Having been a naval aviator, Roy Grumman specified that the absolute last thing to fail on a Hellcat should be the cockpit. He and his engineers protected an F6F pilot with 212 pounds of armor plating plus two more big sheets bracketing the oil tank just ahead of the instrument panel. Typical quotes from pilots who’d brought home battle-damaged Hellcats were: “Mostly holes where the airplane used to be,” and “More air going through it than around it.” One F6F landed with 200 bullet holes.

After the war, most F6Fs were quickly relegated to training and Reserve squadrons, though radar-equipped F6F-5Ns were retained as night fighters. The Hellcat’s combat swan song for the U.S. came over Korea, when six radio-controlled F6F drones, each carrying a finless one-ton bomb, were sent one at a time against a North Korean bridge and a railway tunnel in August and September 1952, flown by a controller in an accompanying two-seat AD-2Q Skyraider. These missions were really proof-of-concept tests, demonstrations rather than serious raids, and they did little damage to anything other than the Hellcats.

The Navy had substantial experience with remote-control Hellcat drones, having converted a number of the readily available, expendable and dependable fighters soon after the war ended. Most were painted a vivid red or orange, occasionally yellow. Four pilotless F6F-5Ks, as the variant was designated, were used during the first Bikini A-bomb test, in July 1946. They were flown through the blast cloud after the explosion’s shock waves dispersed. One went out of control and crashed, and control airplanes picked up two of the three survivors after they emerged from the roiling column of smoke, dust and superheated air. The third Grumman was eventually spotted by radar cruising happily along some 55 miles from Bikini. It too was intercepted and led back to nearby Roi Island, where the three drones were safely landed.

Even today, the contribution of Hellcat drones is felt in air combat: The very first AIM-9 Sidewinder air-to-air missiles were shot at F6F-5Ks flying above the China Lake Naval Ordnance Test Station during 1952 and ’53. The first 12 Sidewinders scored clean misses, but in September 1953 the 13th came within 2 feet of its Hellcat target, which would have destroyed the airplane had the inert test missile been fitted with its proximity fuze and warhead. Sidewinders remain the air combat weapon of choice for every air force that can get their hands on them, and thanks to the Navy, it’s predicted they will stay in the U.S. inventory through most of the 21st century.

Today, five F6F Hellcats are still flying, in the hands of Tom Friedkin, the Commemorative Air Force’s Southern California Wing, Paul Allen’s Flying Heritage Collection, the UK’s Fighter Collection and the Yanks Air Museum. Compared to all the Mustangs, P-40s, Wildcats and Corsairs that show up for airshows and local fly-ins, Hellcats are among the hen’s teeth of U.S. warbirds. They’re rare in part because they had no foreign operators who might have preserved them, beyond the Royal Navy and the French and Uruguayan navies, and because they had no civilian utility as firebombers, aerial sprayers, air racers or executive transports—applications that have saved everything from Bearcats and Tigercats to B-17s and B-26s. Let’s admit it, too, Hellcats just aren’t as colorful and sexy as more frequently restored types.

This may change, however. Three more F6Fs are undergoing restoration to flight status (the Yanks Air Museum’s second Hellcat plus airplanes owned by collector Jack Croul and the Collings Foundation). With the flying fleet eventually to grow by more than half, we could be on the cusp of a Hellcat renaissance. For the airplane that won the Pacific air war and was crucial to securing the islands from which B-29s could fly, it’s about time.

On a sunny August day in 1956, an F6F-5K Hellcat took off from Naval Air Station Point Mugu, northwest of Los Angeles. A pilotless drone, painted bright red with big yellow camera pods on the wingtips, the Hellcat was on its way to the test range to be targeted by air-to-air missiles—probably AIM-7 Sparrows, which were then under development. A pilot on the ground controlled it, much as present-day UAVs are flown. The tired old Grumman made a straight-out departure from Runway 21 and climbed out over the Pacific, which lapped nearly at the departure end of 21.

It soon became apparent that controller and drone were not communicating. The red Hellcat made a stately turn to the left—southeast—as it continued to climb, despite the controller’s constant turn-right command. To the southeast lay the sprawling LA metropolis, hundreds of square miles of cityscape that now lay directly in the path of a runaway 6-ton pilotless fighter filled with more than 200 gallons of aviation fuel.

The Navy needed help, and it lay close at hand. Just five miles north of NAS Point Mugu was Oxnard Air Force Base, home of the “Fighting 437th” Fighter-Interceptor Squadron. The 437th’s rocket-equipped Northrop F-89D all-weather interceptors were tasked with pulverizing any Soviet bombers that might approach the California coast, and they were ready to do it day or night, good weather or bad, anytime, anywhere. Bring it.

A 12-year-old piston-engine fighter cruising at probably 200 mph, unable to even make evasive maneuvers on a California summer day, should be good for a few minutes of live-fire practice, so the Air Force scrambled two F-89Ds loaded with a total of 208 2.75-inch Mighty Mouse air-to-air rockets. The radar-equipped Scorpions caught up with the Hellcat at 30,000 feet, over the fringes of populated LA. The Grumman was maneuvering mindlessly, first turning toward the city, then away, then going deeper into outlying suburban areas. The two F-89D pilots and their back-seat radar operators needed to destroy the Hellcat before it decided to head for Hollywood, and they couldn’t wait too long to do it.

Now the Hellcat was veering toward the western end of Antelope Valley, an area as sparsely populated in 1956 as its name suggests. But then it turned southeast toward downtown LA again. Time to lock and load. First one jet and then the other got the Grumman in their windscreens—they had no gunsights, since the Scorpions supposedly had some sort of “automatic fire control” for their unguided rockets—and then the Fighting 437th ripple-fired, loosing intermittent salvos of Mighty Mice.

Was ever a weapon so appropriately named? Every rocket missed, though they did set a 150-acre brushfire on the ground. A second firing run did no better, although it too set a string of fires, one between an oil field and an explosives factory. A third try emptied the Scorpions’ big wingtip rocket pods: 208 rockets, zippo hits. The last group of salvos, however, became the talk of Palmdale, Calif., where they riddled houses and cars. There were no injuries, fortunately, but the blazes they set took 500 firefighters two days to extinguish.

Meanwhile, the Hellcat declared itself done with this game. Its big R-2800 whickered to a stop, out of fuel, and the old warrior crashed into the empty Mojave Desert east of Palmdale, taking out some power lines as it went down.

Frequent contributor Stephan Wilkinson recommends for further reading: The Grumman Story, by Richard Thruelsen; F6F Hellcat at War, by Cory Graff; Grumman F6F Hellcat, by Corwin Meyer and Steve Ginter; and Grumman F6F Hellcat, by David Anderton.

This feature was originally published in the July 2014 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.