The Empire State inherited a huge hunk of its soul from the Netherlands

On Tuesday, August 27, 1664, New Amsterdam, a harborside settlement at the southern tip of Manhattan Island, was bustling. Carpenters were hammering. Coopers were assembling barrels out of staves and metal hoops. Tavernkeepers were sweeping floors. The town was a miniature Babel, home to speakers of more than 15 languages. Africans, enslaved and free, were everywhere. In multiple Dutch Reformed churches, “dominies,” as the sect called ministers, were preparing sermons. Butcher Asser Levy was serving fellow Jews and anyone else wanting a nice piece of kosher meat.

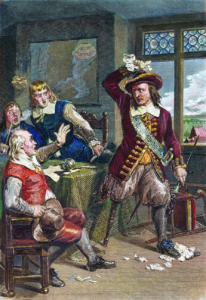

The sight of four warships in the harbor electrified all who saw the vessels, which were flying the English colors. Lately the Netherlands, which owned the colony of New Netherland, had been at odds with England. King Charles II had granted John Winthrop, governor of the English colony Connecticut, a charter assigning Winthrop claim to all territory between Narragansett Bay and the Pacific. That grant included much of New Netherland. English residents of Dutch-ruled towns in Long Island had been chafing under Dutch control, complaining to Peter Stuyvesant, New Netherland’s autocratic director-general. When Winthrop, sent by the British as an emissary, debarked from one of the ships and handed Stuyvesant what the English called “Articles of Capitulation,” Stuyvesant tore the papers to shreds. Piecing together the tatters, other Dutchmen thought the articles’ terms generous—Dutch colonists could keep their property, come and go as they pleased, worship freely, trade as always, and keep their inheritance rules. Local officials would serve out their terms.

The tetchy Stuyvesant wanted to fight. So did the 150 or so Dutch soldiers at Fort Amsterdam at the island’s edge, despite being far outnumbered by the English troops aboard the ships. Most residents feared that if the soldiers got their way they would lose everything. “Those lousy dogs want to fight because they have nothing to lose,” a woman said. “Whereas we have our property here, which we should have to give up.” Other eyes were watching from across the river in Breukelen on Long Island—Englishmen who began forming militias, ready for combat and plunder.

Stuyvesant holed up in the fort. A gunner awaited his order to fire on the invaders. Leading citizens canvassed New Amsterdamers with a petition endorsing capitulation. Tension reigned as August gave way to September; the petition had 93 signatures, including that of Stuyvesant’s son Balthazar, 17. Confronted with the petition, Stuyvesant relented, declaring, “I would much rather be carried out dead.” On September 6, he sent a delegation to work out the details with the English. Two days later, at his 62-acre “Bouwerie,” or estate, north of the town limits, Stuyvesant joined Admiral Richard Nicolls and their deputies in signing the Articles of Capitulation.

Thus ended Dutch rule and New Netherland’s 40-year history, but not Netherlanders’ presence. New York, both city and state, abound with traces of their colonial beginnings. In the city are Dyckman Street, Van Cortlandt Park, Flatbush Avenue, New Utrecht High School, Lefferts Historic House, Harlem, and the Knickerbockers. The colony stretched from the harbor at Manhattan’s foot north through to what became Albany and Schenectady, east across Long Island and west into New Jersey. The Dutch settled along the Delaware River, where they tangled with and eventually drove off the Swedes; and the valley of the Connecticut River, where a tide of English colonists did to the Dutch as the Dutch had done to the Swedes. However, the Dutch left a broad, deep cultural imprint that lasted for more than 250 years.

In 1609, representing the Dutch East India Company, a publicly held entity organized by the government to trade on the far side of the world, Captain Henry Hudson sailed into a North American estuary giving onto the Atlantic. The Englishman’s bosses had the backing of one of Europe’s newest and most powerful nation states, the Netherlands. A watery region on the shoulder of the Continent between German-speaking territory and Belgium, the Netherlands had been breeding sailors for centuries. Having cast off Spanish control and declared independence, the Dutch set up their East India Company in 1602, quickly generating profits from trade in cotton, textiles, porcelain, and especially spices.

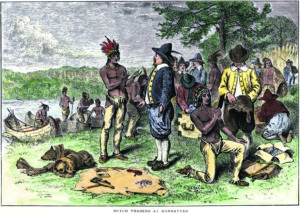

Henry Hudson’s reports about arable soil and many beaver and other fur-bearing animals on what he called the North River led to commerce with native tribes and, in 1624, the arrival of a first wave of colonists. The Dutch West India Company, successor to its easterly predecessor, intended to have the newcomers lock down the Hudson Valley fur trade.

Beaver was the big attraction. “If you lived in Europe in the 17th century, you had to have a hat,” said Dr. Charles Gehring, director of the New Netherland Research Center, “And you needed fur to make those big black hats.” Demand for fur encouraged a relaxed attitude toward Native Americans, who did the trapping, skinning, and curing of pelts, trading the fruits of their labor to the colonists.

The earliest Dutch settlement was in the harbor, on Nut—now Governor’s—Island. A Dutch party traveled 150 miles upriver to establish a bastion at Fort Orange, named for a band on the Dutch flag. Outgrowing Nut Island, colonists claimed the southern tip of a larger island they called Manhattan, a corruption of its Indian place name. Peter Minuit, a Belgian businessman, arrived in 1625, and within the year was the colony’s director, or governor. Minuit offered to buy Manhattan from its historic occupants, the Lenape. Indians saw humans not as owners of land but its stewards. According to Russell Shorto in his book The Island at the Center of the World, the Lenape, seeking an ally to defend them against rival tribes, thought that in accepting Minuit’s offer they were granting the Dutch temporary use of their territory in exchange for taking their side. Between 1624 and 1664, however, about 200 shiploads of immigrants arrived, taking up permanent residence. Not all were Dutch. “It was hard to get the Dutch to immigrate here because the Netherlands’ standard of living was much higher than the rest of Europe,” said David Voorhees of the New Netherland Society. “So they also allowed people to come from other regions.”

To lure investors willing to develop parcels in the wilderness beyond Manhattan, the Dutch West India Company in 1629 introduced the patroon system, an update on feudalism. A lord-like patroon, who need not necessarily come to his holding himself, could send 50 people to the colony and, out of his pocket, stake out land on which to undertake an independent enterprise; his other main expense was the cost of passage for his people and a 5 percent duty on goods they brought, excluding farm tools and cattle. On his turf, the equivalent of a land grant, a patroon could appoint government officials, administer justice and provide security, buy more land from Indians, and have a monopoly over the products of hunting, trapping, and fishing. The patroon could trade in all products of the land except furs, which custom the Company reserved for itself. The patroon’s people had to pay him rent and swear fealty to him.

The patroon system generally was a bust. Under-capitalized and beset by Indian trouble, most patroons went broke. The system’s one success was Rensselaerwijck—or Rensselaerwyck—which stretched along 24 miles of both Hudson banks near Fort Orange. Gem merchant Kiliaen van Rensselaer ruled his namesake fief from Amsterdam, never visiting but underwriting his enterprise into profitability.

New Netherland stood apart from North American colonies under English dominion—especially in regard to trade, religious tolerance, and cultural variation. In 1609, Dutch lawyer Hugo Grotius delineated the doctrine of Freedom of the Seas. Grotius stipulated the oceans to be open to use for trade by all nations, a rebuke to the closed English system, under which that nation’s commercial fleet served and profited from its colonies. The Dutch, who under the Spanish thumb and after had evolved an open-minded approach to trade, religion, and skin color, were free traders in commerce and in thought. The Netherlands in 1579 established the right to be free of persecution for practicing one’s faith. In New Netherland, only the Dutch Reformed Church had the right to establish congregations. However, in the colony as at home, religious dissenters encountered less oppression. New Amsterdam’s Lutherans, for example, had leave to worship in their homes. Besides ethnic Netherlanders, New Amsterdam’s populace came to include not only French-speaking Walloons, Scandinavians, Germans, English—often arriving from neighboring colonies—but Scots, Italians, Sephardic Jews, Native Americans, and Africans.

From the start, New Netherland benefited from enslavement. African bondsmen helped clear land and build structures, doing the heavy lifting and living in cramped quarters. Still, Black slaves in New Netherland had more rights than their counterparts in English colonies—those held in bondage by the Dutch could learn to read, marry, be baptized, testify in court, bring suit, and hire themselves out for wages on days off, a phenomenon that regularly increased the ranks of Blacks in the colony who had purchased their freedom.

The Company recalled Minuit to Amsterdam in the early 1630s, briefly replacing him as director Sebastiaen Krol, then Wouter Van Twiller. Van Twiller, who served 1632-37, increased fur trade with Native Americans and trade with neighboring English colonies, but was recalled for enriching himself extravagantly. His successor, Willem Kieft, arrived in 1638.

Kieft oversaw many changes, beneficent and harsh. In 1639-40, the Company dissolved its fur monopoly, opening the trade to all. According to Dutch New York, edited by Roger Panetta, this led to the subsequent economic boom and population growth in towns like New Utrecht, Midwout—”Midwood,” also known as Flatbush—and Amersfoort in today’s Brooklyn; Vlissingen—Flushing—in what is now Queens; Haarlem on the upper reaches of Manhattan Island; and Wiltwijck—Kingston—in the Hudson Valley. He also appointed the colony’s first advisory body, the Council of Twelve, with whose members he frequently found cause to quarrel.

Kieft undid decades of amity with Native Americans. Against colonists’ advice, he sought to tax local Indians since, he reasoned, Dutch soldiers and sailors were protecting them from other tribes. Resentment toward the levy brought violence and retribution.

In February 1643, Dutch soldiers invaded a Lenape encampment where Jersey City stands, slaughtering more than 80 men, women, and children at the start of “Kieft’s War.” That fall, about 1,500 Native Americans invaded New Netherland, destroying villages and burning farms. Amid mutual brutality, groups of settlers and individual tribes began to negotiate separate peace treaties until, in 1645, Kieft and representatives of key tribes signed a general accord.

Shortly before peace returned, Kieft, responding to a petition by 11 enslaved Africans, created “half-freedom.” This status, given only to the 11 and their families but later extended to others whom the colony knew and trusted, such as Black members of the town watch, the volunteer security force, allowed slaves to own land and residences, provided they worked for the colony as needed and paid an annual fee. Children of half-free parents were still slaves. New Amsterdam created a hamlet for these residents called “Land of the Blacks,” centered in today’s Greenwich Village and sited, Kieft hoped, to serve as a buffer against Indians.

The peace treaty did not erase colonists’ rage at Kieft and his disastrous war. Recalled in 1647—he died on the way in a shipwreck—Kieft was replaced by Peter Stuyvesant, who soon faced two challenges. The first came from Adrien van Der Donck, a liberal lawyer serving on Stuyvesant’s advisory Council of Nine, successor to Kieft’s Council of Twelve. Van der Donck and supporters wanted to throw off Dutch West India Company control. In its place, they proposed to have New Netherland governed by a representative body answering to the crown. In Amsterdam, van der Donck argued for the change before the States-General, the national legislature. The States-General approved the plan in 1652. The First Anglo-Dutch War prevented implementation. The Treaty of Westminster ended that conflict in 1654 but van der Donck’s plan remained in limbo. He returned to his large estate north of Manhattan, where he was known as the “Yonk Herr”—“Young Gentleman”—which evolved into “Yonkers.”

Stuyvesant’s second challenge occurred up north. On land adjoining Fort Orange, a freebooting, beaver pelt-trading village took root. The hamlet’s wealth interested both Stuyvesant and Brant van Slichtenhorst, director of Rensselaerwyck. Claiming ultimate authority over Rensselaerwyck, van Slichtenhorst forbade the Dutch West India Company from quarrying stone or cutting wood on its lands. Director van Slichtenhorst began building houses next to Fort Orange; Stuyvesant, for security reasons, then forbade construction within cannon range of the fort. Van Slichtenhorst ignored his orders. The standoff lasted until 1652, when Stuyvesant sailed upriver with troops and declared the settlement to be the Company’s. He named the village Beverwijck—pronounced “bay vurr vake”—from the Dutch for “place of beavers.”

Under Stuyvesant, New Netherland’s habitual religious freedom was severely tested. In 1653, Lutherans there requested permission to bring over a pastor. In response, Stuyvesant forbade even private Lutheran services, fined violators, and forced the baptism of Lutheran children as Dutch Reformed congregants. The crown countermanded his strictures. In 1654, a ship arrived carrying 23 Jewish refugees; they were fleeing Recife, Brazil, a Dutch colony conquered by the Portuguese. Strident Dutch Reformed believer Stuyvesant, calling Jews “such hateful enemies and blasphemers of the name of Christ,” petitioned the Company for permission to expel the newcomers. The Company, whose stockholders included Jewish investors, ruled that Jews had freedom to worship in New Netherland. Stuyvesant also took out after Quakers. In 1662, Vlissingen resident John Bowne, an English immigrant, allowed a Quaker meeting in his house. Stuyvesant had Bowne arrested. Assessed a fine, Bowne refused to pay. He was sent to Holland for a Company trial. The Company ordered Stuyvesant to leave Quakers be.

Stuyvesant was more kindly toward Native Americans. The one major Indian/Dutch conflict on his watch, the “Peach Tree War,” did not involve peaches or land but fury on the part of the Susquehannock nation, close trading partners of Swedes settled along the Delaware River. In September 1655, the Susquehannocks attacked New Amsterdam and settlements in the Hudson Valley in retaliation for Stuyvesant’s conquest of New Sweden. Afterwards, Stuyvesant bought back land the tribe had taken west of the Hudson.

The Treaty of Westminster had been keeping the peace between England and the Netherlands for 10 years when that August 1664 English display of arms at New Amsterdam surprised residents. However, the preceding March England’s King Charles II had promised his brother James, Duke of York and Albany—York was an English city, Albany a Scots city—that he could have New Netherland, and now James had sent a force to make that be so. When New Netherland became New York, New Amsterdam became New York City and Beverwyck became Albany. One of the Dutch government’s last acts was to emancipate “half-free” Africans, lest the English enslave them anew. A second Anglo-Dutch War in 1665-67 had no effect on New York. In 1673, during a third Anglo-Dutch War, the Netherlands took back its colony. New York City became “New Orange.” Within the year the combatants came to terms with the second Treaty of Westminster. Britain got New York back while the Dutch got Surinam, on the northeastern coast of South America, with its valuable sugar plantations.

In the late 1600s came a new stream of immigrants. French Protestants, or Huguenots, founded the town of New Paltz in the Hudson Valley. Huguenots, like the Dutch, were Calvinists, and the groups formed a bond. Dutch settlers soon started moving into the town. Many Huguenots learned Dutch, married Dutch spouses, and attended Dutch Reformed services. Distance from cosmopolitan New York City reduced the Hudson Valley’s exposure to influences other than the Netherlands. No matter who controlled New York, Dutch residents there maintained their language and customs into the early 1800s, and longer in some locales.

The Dutch Reformed Church helped maintain use of the Dutch language in New York. For decades after the British takeover, congregations’ dominies came directly from Holland; naturally, they conducted services in Dutch. In 1754, American congregants founded their own governing body, or “classis.” As more Dutch Reformed clergymen trained in the colony and later the state, an interregnum began in which most churches offered services in both Dutch and English. Brooklyn’s Old First Reformed Church “was bilingual from 1737 to 1824,” said the Reverend Daniel Meeter, that congregation’s current minister. “By that time, many people spoke a Dutch dialect [with many English words], but church services were always in ‘good Dutch’ or ‘book Dutch.’ Many people who spoke vernacular Dutch found it easier to understand English than ‘book Dutch.’” The church’s Dutch character, Meeter added, “slipped away” as congregants intermarried with other ethnic groups.

Dutch practices lived on from enslaved enclaves to the upper crust. Isabella Baumfree, an African American who later became an anti-slavery crusader and renamed herself Sojourner Truth, grew up in the Hudson Valley and until age nine spoke only Dutch. One highlight of Afro-Dutch life was the annual spring “Pinkster” (Pentecost) festival. The book Dutch New York Histories describes Pinkster in the Albany of the early 1800s. Slaves got time off to participate. Festivities included a parade, games, music, drinking, and dancing to the fiddle and African drum. An Angola-born man known as King Charles, dressed in British military costume, presided over the merriment. Albany outlawed the festival in 1811, possibly out of fear that the event could promote a slave uprising. New York State abolished slavery in 1827.

In the early 1800s, writer Washington Irving popularized Dutch New York culture, first with his History of New York under the pseudonym “Diedrich Knickerbocker,” then with “Rip Van Winkle,” “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” and other short stories rooted in Dutch Hudson Valley folklore (“What’s in a Name?” August 2017). These tales traded in nostalgia for a bygone era when life presumably was more rural and less hurried.

Spoken Dutch hung on. “Women in the countryside held onto Dutch the longest,” said Gehring. “The men had to go out into the world and speak English, but rural women still spoke Dutch at home and taught it to their children.” As late as 1910, researchers counted 200 older residents of nearby Bergen County, New Jersey, speaking “Jersey Dutch.” However, compulsory schooling in English, mass media, and waves of English-speaking suburbanites doomed the old language. When Dutch withered, so did Dutch handicrafts. Collectors prize them. “We had several kasts [elaborately carved wooden cabinets] that were handed down in our family,” said Voorhees. “When they went out of fashion, they were used as chicken coops.”

Assimilated Dutch Americans became conspicuous in New York’s political and financial elite. Three American presidents—Martin Van Buren—who spoke only Dutch until he started school—Theodore Roosevelt, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt had Dutch ancestry. The wealthy Schermerhorns were used by Martin Scorsese to symbolize Manhattan’s Civil War-era upper class in his film The Gangs of New York. During the Gilded Age, Cornelius Vanderbilt rose from ferryboat operator to steamship and railroad magnate. Still, Voorhees said, it’s “a great myth” that the Dutch as a whole became wealthy and powerful. “A handful became prominent,” he said. “The rest were farmers, or whatever.”

_____

Dutch Traces

Americans of Dutch ancestry have continued to distinguish themselves: New York City Mayor John. V. Lindsay, actors Henry Fonda and Humphrey Bogart, and rock star Bruce Springsteen, whose father’s family is part-Jersey Dutch. Dutch houses, barns and churches dot the former New Netherland. Most date to the English and early American periods, built by Dutch families in a Dutch style. —Raanan Geberer

On Huguenot Street in New Paltz, New York (left top), seven 18th century stone houses, some in the vintage gable-roofed Dutch style, are open to the public.

Senate House in Kingston, New York, (left bottom) was built in 1676 by Wessel Ten Broeck. After independence, Kingston was New York State’s capital, and in 1777 the Ten Broeck resident hosted the state Senate’s first meeting. Furnishings include many paintings by John Vanderlyn, a Kingston-born Dutch American artist renowned in the early 1800s

The Old Stone House in Park Slope, Brooklyn, began as a farmhouse built in 1699 by Dutch immigrant Claes Vechte and son Hendrick. In 1776, the dwelling played a pivotal part in the Battle of Brooklyn. In the 1880s, it served as a clubhouse for the team that later became the Brooklyn Dodgers. Destroyed in 1897, in the 1930s it was reconstructed using many original stones. Today, it’s a museum.

The Schenck House was built by Jan Martense Schenck in Flatlands—then a rural town, now a Brooklyn neighborhood—in 1675. In the 1950s, the Brooklyn Museum moved the house inside its building, renovated it and furnished it with colonial furniture.

Lefferts Historic House in Prospect Park, Brooklyn, was built by Continental Army Lieutenant Pieter Lefferts in 1783. The Lefferts family held onto the wooden Dutch-style gabled farmhouse through much of the 19th century. Visitors are invited to participate in candle-making, butter-churning, and sewing and take part in seasonal celebrations, including Pinkster.

Dyckman Farmhouse in Inwood, in Upper Manhattan, was built in 1784-85 to replace a house destroyed in the Revolution. The Dyckmans owned the property until the 1860s. Let out to tenant farmers and allowed to deteriorate, the house was bought back by the Dyckmans in 1915. The family restored the house and grounds and presented the parcel to New York City as a museum. In the HBO series “Mad Men,” the character Pete Campbell is a Dyckman descendant.

Van Cortlandt House Museum in the Bronx was built in 1748 by Frederick Van Cortlandt on land where he grew and milled grain using slave labor. The English manor style house has a front stoop, carvings of grotesque faces above the front windows to ward off the “evil eye” and other Dutch features. In 1888, the family sold the property to the city, which converted the plantation into a park. The house became a museum in 1897.

During the 1680s and 1690s, Dutch-born Frederick Phillipse, a merchant, farmer and slave trader, built elegant Phillipse Manor Hall in Yonkers, the smaller Phillipsburg Manor House further north in Sleepy Hollow, and the Old Dutch Church of Sleepy Hollow. The loyalist Phillipses fled to England after the Revolution. The church, invoked throughout “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” especially when Ichabod Crane thinks he can escape doom by reaching the church bridge, still is a place of worship. The manor houses are museums.

New Netherland may be history, but its presence persists in everyday speech. The Dutch Sinterklass evolved into “Santa Claus.” “Boss” derives from baes. Cookie comes from koekje, cole slaw from coolsa, and the Dutch brought donuts, which they called oylkoek.