London was still smoldering when France’s King Louis XIV proclaimed his life’s driving force. The year was 1666, and the Great Fire had just reduced the capital of his mortal English enemies to a charred barren.

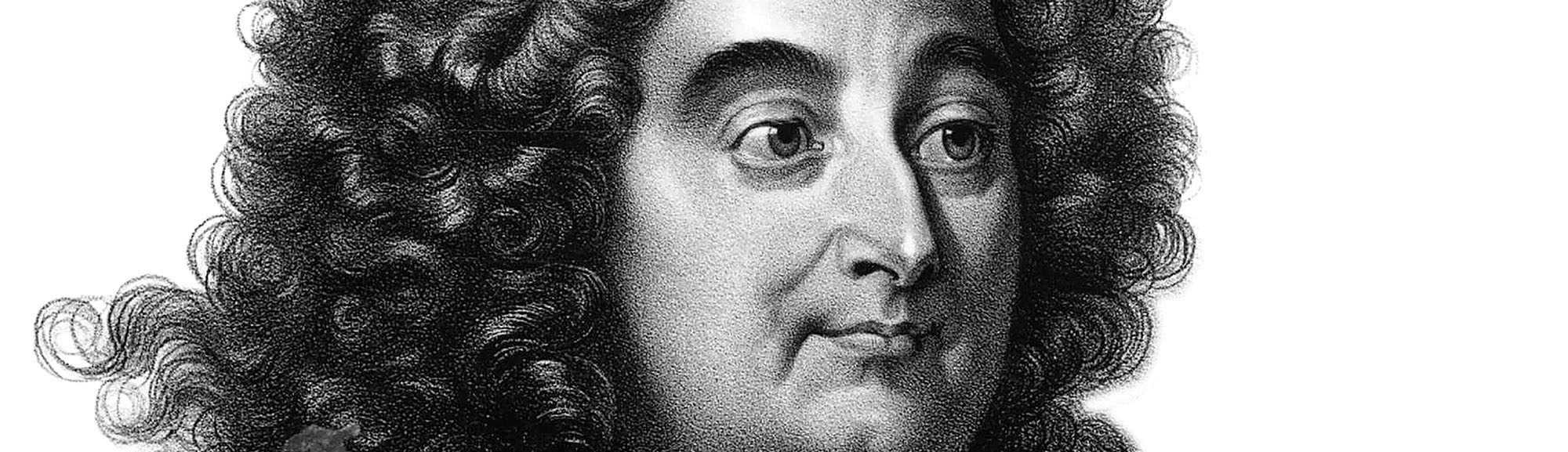

Stirred by an inner flame of his own, Louis proclaimed, “My dominant passion is certainly love of glory.” His thirst for la gloire had already moved him to claim a hefty share of fading Spain’s continental possessions. Yet there was little prestige to be gained from kicking around the bankrupt, overextended Spaniards. The monarch known to history as the “Sun King” cast his gaze elsewhere, and he discerned a quarry with much to offer in his nominal allies the wealthy Dutch.

King Louis’ decision to extend his quest for glory to the Netherlands seemed, to him at least, a logical one. Though the forerunner of the Dutch Republic had been a military ally of France for decades, the Hollanders had become major economic rivals. Having largely replaced the Portuguese as masters of commerce between Europe and the wealthy Far East, the ardently capitalistic Dutch grew steadily richer through their domination of the Molucca Islands (in present-day Indonesia) and stranglehold on the lucrative spice trade.

To justify his decision to go to war, Louis could point to marked political and religious differences. The Dutch had broken with the Spanish monarchy to form their democratic republic, while France remained the domain of an absolute monarch—the Sun King himself. Moreover, the Dutch dared to challenge his authority, in 1668 forming a diplomatic alliance with England and Sweden that forced Louis to end his ongoing war against the Spanish Netherlands and return conquered territory. Though both the Dutch and French were ostensibly Christian, the Protestant Hollanders forbade Catholicism in the Netherlands, while the hard-core Catholic French king ultimately outlawed Protestantism within his domain.

But profit and glory were Louis’ actual motives for wanting to conquer the rich and powerful Hollanders. To humble the men in wooden shoes would not only line Louis’ pockets but also gain him far-reaching acclaim as his nation’s champion in a struggle with a dangerous ideological opponent. Thus in May 1672 he mobilized his armies and launched the Franco-Dutch War.

Seeking a quick victory, Louis had amassed an impressive force with which to conquer the Dutch. Some 120,000 men in two columns first advanced toward Maastricht in the southeast part of the Netherlands (sandwiched between present-day Germany and Belgium), but then bypassed the fortress city and followed the Rhine River northwest toward Amsterdam. As the French closed within two days’ march of the capital, the Dutch opened their dikes, establishing a defensive water line by flooding the surrounding countryside in 4 feet of excruciatingly cold seawater.

But by then the French soldiers were so far inside Holland that the panicked Dutch people revolted, demanding the appointment of William of Orange as stadtholder, or de facto head of state, before lynching the politicians they blamed for leading them to war. The government in waterlocked Amsterdam meanwhile sought a truce to spare both sides a bloodbath in the looming siege of the capital. Louis, however, demanded such harsh concessions that the Dutch rallied around William.

A hotheaded, combat-loving firebrand, William proved a largely inept field commander. Yet in defeat he managed to inflict grievous losses on his opponents, and the fervently Protestant stadtholder hated Louis with a passion. Furthermore, he managed to enlist allies with his energetic anti-French exhortations.

Frustrated by the swamped countryside and William’s fanatical resistance, Louis turned away from Amsterdam to instead invest the bypassed fortress city of Maastricht. Tasked with the siege was Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban, a talented young military engineer with a proven ability to both build and overcome defensive works. Vauban devised an intricate network of trenches that within a few weeks brought about Maastricht’s fall.

Under Vauban’s supervision the French captured every Dutch fortress city they encountered, but William kept coaxing a steady stream of new allies onto the battlefield to fight the French. Louis resorted to subterfuge, dispatching regiments of spies and subversives to nurture disaffection and outright revolt among William’s countrymen and newfound allies. In the end, although opposed by strong and capable enemies, the French king manipulated them into impotence and ultimately prevailed. In the subsequent 1678–79 Nijmegen peace treaties, his demoralized and confused adversaries conceded him vast tracts of Europe.

The Sun King’s adventure in the Netherlands had helped turn France into the undisputed pre-eminent power on the Continent. Louis oversaw a sprawling domain molded to his will, with few voices of dissent from his subjects of various nationalities. Yet his belief in a divine right to absolute power—and, of course, his unquenchable thirst for glory—inevitably drove him from the comforts of peace to lead his nation back to war.

Following his victory in the Franco-Dutch War Louis undertook a series of actions intended to stabilize his nation’s borders and reinforce his various territorial claims. The most momentous of these came in the fall of 1688, when the Sun King crossed the Rhine seeking to coerce Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I into acknowledging France’s hegemony in Western Europe. Louis’ advance did not have the intended result, however, instead driving Leopold to band together with Spain, the Dutch Republic, Savoy, England and other European allies to form the Grand Alliance, which promptly declared war on France.

The resulting Nine Years’ War had Louis fighting on two fronts—in the east, where his forces took numerous cities in the Rhineland, and in the west against the English and Dutch. France also supported the ultimately futile efforts of deposed King James II, a fellow Catholic, to reclaim the English throne from William III—Louis’ old nemesis William of Orange. The war also saw extensive fighting in Italy, as well as in Spain’s Catalonia region. Though France generally did well in the conflict, by 1697 the huge drain on Louis’ treasury convinced him to agree to the Treaty of Ryswick and renounce some of his recent gains.

Louis had been on the throne ostensibly since age 4, and by the time the Nine Years’ War ended, the 59-year-old Sun King was more than ready to retire, at least as much as a ruling monarch of his stature could. His wife, Maria Theresa of Spain, had died in 1683, after which the aging monarch had shed his many mistresses and married 48-year-old Françoise d’Aubigné, pious onetime governess to one of the king’s former mistresses. As the 17th century waned, Louis surrounded himself with family—including his dozen-plus children, both acknowledged and illegitimate—and sought finally to give over the rigors of campaigning.

Louis found it difficult to rest on his considerable laurels, however, for a new generation of enemies was emerging to challenge him. The determined newcomers were confident they could cut down to size the aging monarch who had instilled such fear in their fathers. Yet the Sun King would rouse himself from the comforts of hearth and home to show how powerfully an old lion can bite.

As the 18th century dawned, the tangled political machinations in Europe conspired to make Louis XIV appear to ruling contemporaries a greater-than-ever peril. Spain’s frail and sickly Hapsburg king, Charles II, had no direct heir, although Hapsburg Archduke Charles of Austria was a strong claimant. But in the will he dictated just before his death at age 38 on Nov. 1, 1700, Charles II left the throne to grandnephew Philip, Duke of Anjou, who was also Louis’ grandson. The French king was poised to gain unfettered access to the considerable stores of gold and silver Spain had extracted from its New World colonies. The Sun King’s rivals in turn feared such a huge injection of capital would only fuel Louis’ penchant for territorial expansion and lust for glory. The French king’s actions in the two years following Philip’s ascension did little to dispel their fear, as he declined to remove his grandson from the House of Bourbon line of succession, raising the very real possibility Philip might one day rule over both Spain and France.

The response to Louis’ actions was swift. England, the Dutch Republic, Austria and other states within the Holy Roman Empire allied themselves against the French king and formally supported Archduke Charles’ claim to the Spanish throne. The reconstituted Grand Alliance declared war on France in May 1702, and Louis once again found himself confronting a formidable array of hostile powers.

While the French king remained a political force to be reckoned with, he faced several challenges in the War of the Spanish Succession. Louis’ best field commander in the Franco-Dutch War, Henri de La Tour d’Auvergne, vicomte de Turenne, had died in one of the final battles of that fray, and the brilliant Vauban had quibbled with his king and fallen out of royal favor. Moreover, France’s coffers had never recovered from the expenses of the Nine Years’ War, even with the recent infusion of Spanish money. The confederation squaring off against France, meanwhile, had organized a hardy leadership.

A disillusioned expatriate Frenchman, Prince Eugene of Savoy, was expertly guiding Austria’s imperial forces. Louis’ nemesis William III of England had died, leaving John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough, in charge of that nation’s forces. Churchill, like Eugene, had fought as a young soldier in the previous war with France, and his courage and meticulous study of warfare made him one of his nation’s greatest warriors.

Nevertheless, at the Sept. 20, 1703, Battle of Höchstädt, in Bavaria, the French under Marshal Claude-Louis-Hector de Villars managed to trounce the opposing Austrians, inflicting more than 10,000 casualties for the loss of 1,000 men. The situation appeared dire for the coalition. But in 1704 Churchill, after massing a sizable force in Flanders, struck out southwest on a route that made it impossible for the French to ascertain his destination and concentrate their troops accordingly. He finally dug into the French and their Bavarian allies on July 2 at Donauwörth, cutting them to pieces.

Churchill shared William III’s love of combat, but was a far more competent field commander known for uncompromising tactics. When assaulting a fortification, for example, he skipped the formality of offering its commander a chance to surrender, instead sending waves of men against the enemy defenses. Churchill also refused to parole enemy soldiers, thus denying the rank and file an opportunity to bear arms against him a second time.

In the wake of his victory at Donauwörth Churchill linked up with Eugene, and on August 13 they destroyed a numerically superior French-Bavarian army on the banks of the Danube near Blenheim, a decisive victory that essentially knocked Bavaria out of the war. The Grand Alliance further rocked the French back on their heels in Italy and the Mediterranean, where the British seized Gibraltar. The victories also crushed Louis’ hopes for a quick war.

Things went from bad to worse for the French. In 1706 Churchill trounced Louis’ elderly favorite marshal, François de Neufville, duc de Villeroi, at Ramillies; allied forces drove the French from the Netherlands; Eugene upended Louis’ southern forces outside Turin, Italy; and an allied army reached Madrid, threatening Louis’ grandson. In 1708 Churchill and Eugene again teamed up to defeat the French in Flanders and occupy northern France. Meanwhile, the combined fleets of the newly declared United Kingdom and Holland established firm control of the Mediterranean and North Atlantic, blockading French ports. Imported goods became a rarity, and prices soared. Then nature itself delivered a severe blow.

The winter of 1708–09 was the harshest in recorded history. France’s just-planted wheat crop died in the rock-hard soil, while the numbing cold killed half the nation’s livestock. Famine was widespread. Louis’ pious wife told him God was punishing him for inciting the Dutch war. The Sun King believed her and sought peace from his enemies.

In the spring of 1709, when French Foreign Minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert, marquis de Torcy, traveled to Holland for negotiations, the allies hurled a set of brutally humiliating terms at him. Among the 40 articles were demands that the French surrender all their conquests and that Louis not only desist all aid to his grandson in Spain but also force Philip to abdicate in favor of Archduke Charles. Although broken in spirit and sick of the misery constant war was visiting on his country and people, the proud old monarch could not bring himself to bow so low to his foes. “If I must make war,” he replied to the demands, “I would rather fight my enemies than my children.”

Backed into a corner with his loved ones behind him, Louis XIV decided on a wholly uncharacteristic course of action—the absolute monarch turned to his people for help.

In June 1709 the French king distributed an open letter to his military governors, provincial authorities and bishops, outlining the impossibility of the allied requirements and appealing directly to the citizens to come to their country’s aid:

I can say that I have done violence to my character… to procure promptly a peace for my subjects even at the expense of my personal satisfaction, and perhaps even to my honor.…I can no longer see any alternative to take other than to prepare to defend ourselves. To make them see that a united France is greater than all the powers assembled by force and artifice to overwhelm it, at this hour I have put into effect the most extraordinary measures that we have used on similar occasions to procure the money indispensable for the glory and security of the state.…I have come to ask…your aid in this encounter that involves your safety. By the efforts that we shall make together, our foes will understand that we are not to be put upon.

Louis’ plea struck a resounding chord with his subjects, who immediately rallied around king and country. Gold cascaded into the coffers, while malnourished men from 16 to 60 rushed to enlist in an army the allies did not notice growing. Fed by little more than patriotism, recruits toiled on fortifications and drilled ceaselessly under the direction of Marshal Villars, who knew the only real advantage they would have over the battle-tested, numerically superior Grand Alliance troops was desperation.

Meanwhile, Churchill besieged the fortress city of Tournai, in Flanders, which finally fell in early September, then moved east toward Mons, threatening to outflank the French lines. Recognizing the threat, Louis sent Villars to intercept the allies. Correctly assuming Churchill would never pass up a shot at what appeared an easy victory, Villars conspicuously massed his troops outside the nondescript town of Malplaquet. Sure enough, the pugnacious British commander made straight for them.

Villars’ choice of location was a stroke of genius. Dense forests protected his flanks. From their bristling defensive positions the French employed cannons and muskets with greater accuracy than Churchill had anticipated, repulsing successive waves of brightly clad allied attackers. Using enfilading tactics Villars had seen before and was expecting, Churchill wasted thousands of men in advances shattered by withering fire from a far larger French force than he had dreamed of encountering.

As Villars and his men were first to leave the field at Malplaquet, Churchill brazenly claimed success, but it was a cripplingly expensive Pyrrhic victory. While the French had sustained some 10,000 casualties, allied losses were nearly double that number. “If it please God to give your majesty’s enemies another such victory,” Villars reported to his sovereign, “they are undone.”

The British Parliament, shocked by the bloodbath and impelled by a war-weary public, gradually pulled back from its hawkish stance and sought a separate peace with France, and the Grand Alliance ultimately crumbled. In a series of treaties signed in the Dutch city of Utrecht in 1713 the allies recognized Philip’s claim to the Spanish throne in exchange for his renunciation of any future claim to the French throne. Despite concessions to the British in North America, Louis had consolidated his realm—and just in time. The 76-year-old sovereign died of gangrene on Sept. 1, 1715, after a reign of 72 years—still the longest in European history. Yet the Sun King’s triumph would ultimately prove fatal to the French absolute monarchy.

Though Louis XIV had no way of knowing it, the brilliant manner in which he had saved his kingdom—namely, his self-abasing appeal to his subjects—had sown the seeds of an idea that by the end of the century would transform the French system of government. No longer in awe of its ruling elite, the citoyens began to wonder why they should continue to pay obeisance to a throne with life-and-death authority over millions.

In 1789 Gallic royal absolutism would die in the French Revolution, as some of the great-great-grandchildren of those who had sacrificially preserved the realm of Louis XIV rose against the House of Bourbon. In rallying his countrymen to topple his foes at Malplaquet, the Sun King had both saved and doomed his way of life.

Kelly Bell has written for World War II, Vietnam and other magazines. For further reading he recommends The Great Marlborough and His Duchess, by Virginia Cowles; War and Rural Life in the Early Modern Low Countries, by Myron P. Gutmann; and Europe in the Age of Louis XIV, by Ragnhild M. Hatton.