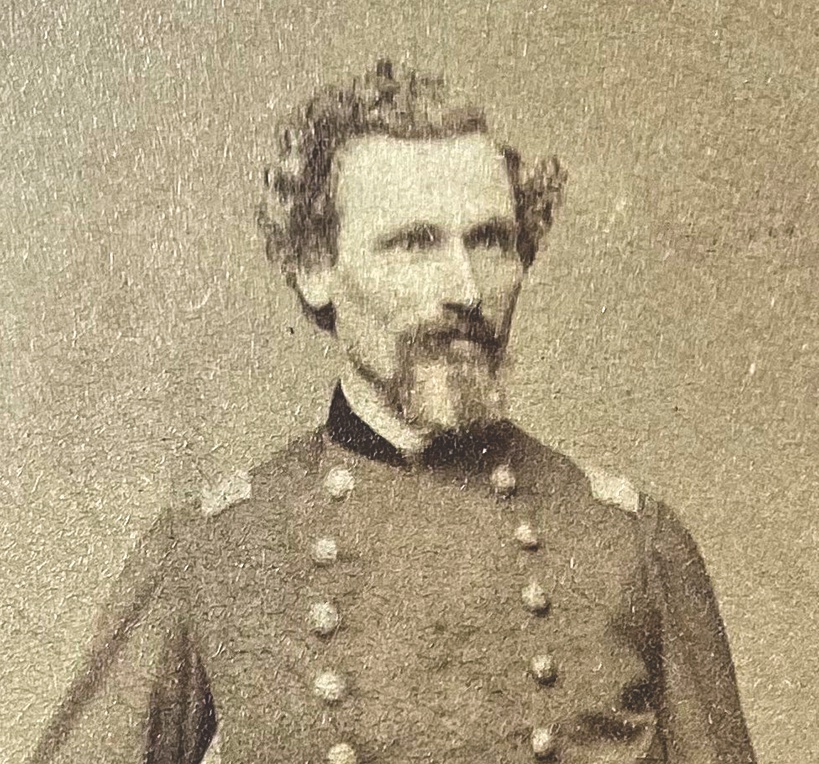

Sometimes a man is judged entirely by a single act or rash of poor choices over a certain period, but it is often necessary to examine an entire life to gauge one’s true character. That was the case for Colonel Alfred Warren Taylor, who was cashiered for drunkenness in 1862 and, nearly two years later, attempted suicide. For the citizens of Memphis, Taylor fortunately didn’t succeed. In 1873, the once-disgraced colonel turned hero by single-handedly saving a neighbor’s home engulfed in flames, likely preventing a fire from spreading throughout the city. Five years later, during the city’s devastating yellow fever epidemic, he was “conspicuous” in providing relief to his sick and dying fellow citizens, even at risk to his own health and livelihood. Indeed, his selflessness during the crisis ultimately killed him in October 1878 when he contracted the deadly disease.

A Mexican War veteran, Taylor had a promising start in the Civil War, appointed a captain in the 4th New York Infantry (1st Scott Life Guards) on April 24, 1861. A little more than two weeks later, he was promoted to colonel. That August, however, he was reportedly so drunk during a parade in Baltimore that he was unable to drill his regiment or communicate with his superior, Maj. Gen. John Dix. Some of Taylor’s fellow officers came to his defense and testified during his court-martial that he hadn’t been as inebriated as the reports suggested. But reports of earlier drunken escapades in New York City helped seal his fate. The court recommended that Taylor be cashiered out of the Army.

Taylor’s lawyer successfully appealed to President Abraham Lincoln to have the colonel reinstated, recalling,

“I was with Colonel Taylor when he was restored to his regiment. His men cheered him as he entered camp. When he left for New York on business, the whole 800 men ranged along the road and gave him three cheers.”

Nevertheless, less than three months later, on July 7, 1862, Taylor resigned his commission, apparently because of friction among his officers. He relocated to Memphis and opened a shop selling military goods.

On the evening of May 24, 1864—days after informing his friends that he intended to commit suicide—Taylor shot himself in the left breast. He was found lying senseless in his home, the pistol at his side. Despite a serious wound to his left lung, he recovered.

Taylor took advantage of the second chance at life. On May 13, 1873, when a fire broke out at his neighbor’s home, he single-handedly began to douse the flames with buckets of water and subdued the conflagration before fire engines arrived.

When yellow fever ravaged Memphis in 1878, Taylor’s friends urged him to leave the city. In September, roughly 200 people were dying per day. Taylor joined the Citizens’ Relief Committee, which distributed food, soap, candles, bedding, etc., to those in need. “He was conspicuous as a member of the…committee, and was zealous and punctual in the discharge of [his] duties,” declared The Memphis Daily Appeal. “To the last he did his duty and stood by his fated fellow-citizens of Memphis so long as he had health and life.”

Taylor became sick and succumbed on October 5. He was buried along with other yellow fever victims in Memphis’ Elmwood Cemetery.