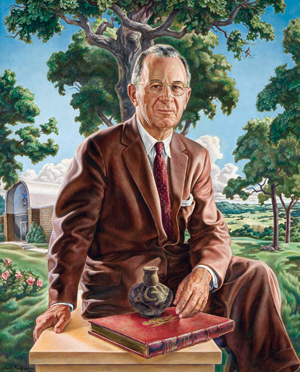

Thomas Gilcrease got the idea to collect art while touring Europe. He got the funds in Oklahoma, where he was raised and made his fortune.

Gilcrease was born in 1890 in Louisiana, but his growing family soon moved to his one-fourth Creek mother’s homeland in Oklahoma Territory, where his father ran a cotton gin. When the government split reservation land into privately owned parcels, Gilcrease’s Creek heritage entitled him to a 160-acre allotment that turned out to be rich with oil. Wildcatters discovered the Glenn Pool reserve in 1905, and by 1917 more than 30 producing oil wells dotted Gilcrease’s land. In 1922 he started his own Gilcrease Oil Co.

Fast forward two decades. Gilcrease had established his company headquarters in San Antonio, Texas, and an office in Paris. His extensive European travels in turn led him to start collecting art, while his Indian heritage and Western roots made those the focus of his collection. In 1943 he opened the Gilcrease Museum at the oil company headquarters in San Antonio, and when the company moved to Tulsa, he opened a public gallery on his estate there.

Over the next several years oil prices dropped, and Gilcrease faced debts galore. As he mulled selling off his art, Tulsa organized a 1954 bond election to pay his debts, and Gilcrease deeded his massive collection, buildings and all, to the city.

That’s the history of the museum in a nutshell, but it doesn’t begin to tell the story. The collection—comprising nearly a half-million artworks, artifacts, books and other materials—does that. Suffice it to say only 6 percent of the collection is on display at any given time.

“Gilcrease wanted to put together a collection that would do for the United States what European museums had done for Europe,” says Laura Fry, senior curator at the Gilcrease since leaving the prestigious Tacoma (Wash.) Art Museum in 2015. “It’s just as significant and carries the same historic weight.”

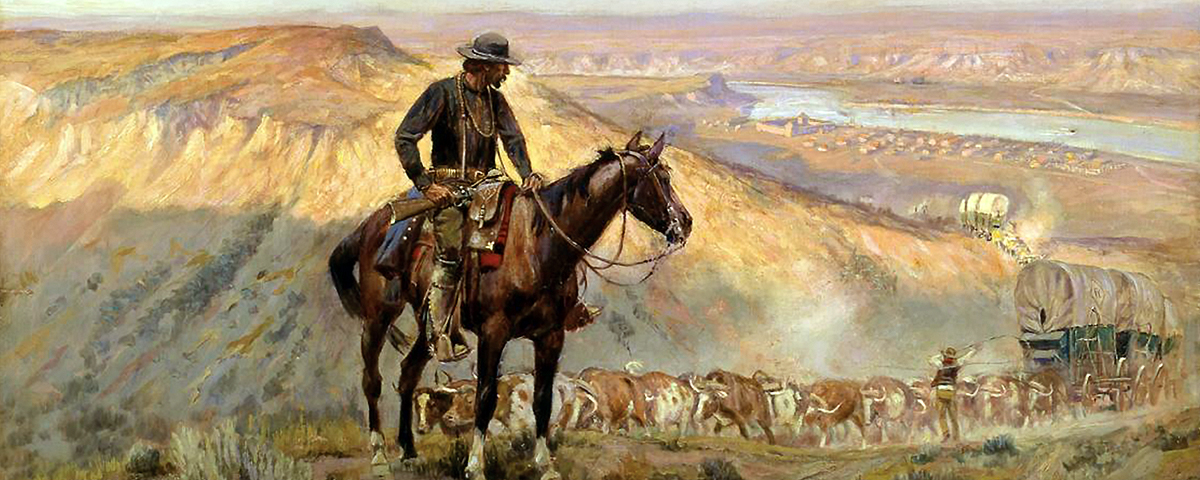

At the heart of the collection are more than 12,000 works of fine art, featuring standouts by such Western icons as Frederic Remington, including 18 of his 22 bronzes, as well as his thought-provoking 1908 oil on canvas With the Eye of the Mind. Also well represented is Charles M. Russell, from his iconic 1909 oil on canvas Wagon Boss to preparatory sketches, illustrated letters and some 13,000 other personal items, objects and images. Gilcrease was also an admirer of Joseph Henry Sharp, a founding member of New Mexico’s Taos Society of Artists. The museum founder purchased almost 350 of Sharp’s works, 200 from the artist personally.

“Gilcrease far outpaced his contemporaries, not only in sheer number of acquisitions but also in the breadth and elasticity of his collecting vision,” Byron Price writes in his introduction to Treasures of Gilcrease: Selections From the Permanent Collection. “Besides securing stunning artworks, the Oklahoman bought thousands of rare books, manuscripts and documents, including certified copies of the U.S. Declaration of Independence and of the Articles of Confederation.”

Visitors also find works by George Catlin, Albert Bierstadt, Thomas Moran, Alfred Jacob Miller, Olaf Seltzer and many others. Chiricahua Apache sculptor Allan Houser’s outdoor bronze Sacred Rain Arrow graces the museum entrance. Gilcrease also supported young Indian artists, collecting and even commissioning works from Woody Crumbo, Willard Stone and Acee Blue Eagle.

Gilcrease became fascinated with archaeology and ethnology and financed field excavations of Mississippi Valley Indian mounds. Reflecting his interest, the museum’s anthropology collection features hundreds of thousands of objects.

But the Gilcrease isn’t just about the past. Through August 27 the museum presents “Textured Portraits,” featuring Ken Blackbird’s photos of reservation life in present-day Montana and Wyoming, while through December it hosts “The Essence of Place,” an exhibition of photographer David Halpern’s black-and-white Western scenics.

Nor is the Gilcrease solely focused on Western art and history. You’ll also find works by Thomas Eakins, Charles Willson Peale, John Singleton Copley, Winslow Homer, John James Audubon and William Merritt Chase. The archival collection, housed at the Gilcrease’s Helmerich Center for American Research, includes more than 100,000 items.

Gilcrease died on May 6, 1962, and is interred on the museum grounds. “Every man must leave a track, and it might as well be a good one,” was his personal philosophy. His art collection and the museum that bears his name have certainly left a good track, and their future appears secure. In 2008 the city of Tulsa partnered with the University of Tulsa to preserve and advance the Gilcrease. WW