Federal authority gathered steam in constitutional battle over centralization

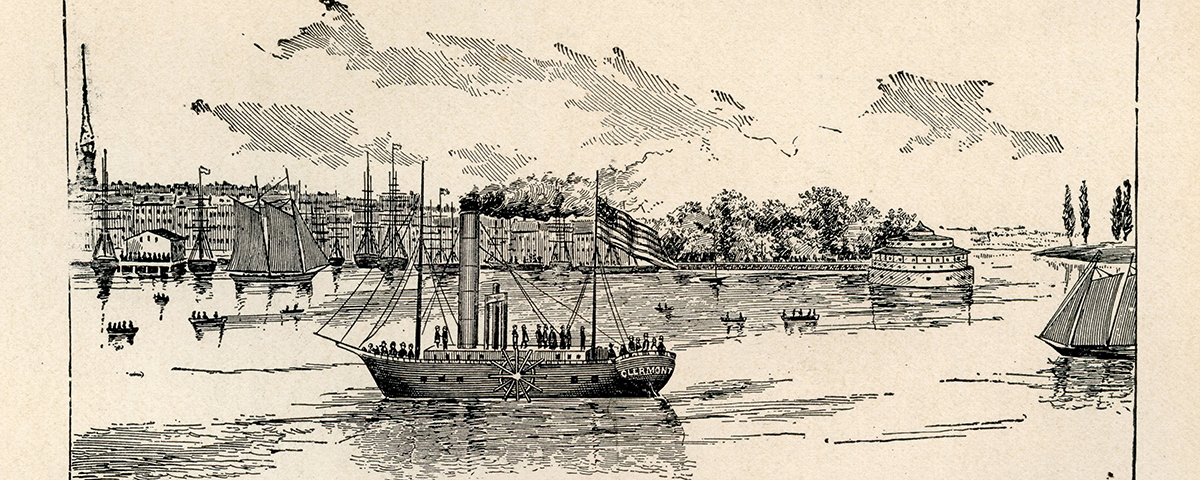

At 1 p.m. on August 17, 1807, a 150-foot vessel’s crew cast off from a dock near Greenwich Village on Manhattan Island, changing the course of American history. Two 15-foot steam-driven side wheels powered the ship to and from Albany on the Hudson River. The steamship’s introduction made feasible rapid, reliable transport of raw materials and finished goods, ushering in the industrial revolution.

States saw in the North River Steamboat of Clermont and its maiden voyage a path to prosperity if they could offer steamship routes on

waters within their borders. Some states were encouraging private road building by granting exclusive franchises empowering holders to charge regulated tolls. Doing so for shipping, states promised investors exclusive access to rivers between given ports—until conflicts between franchise-holders led to a revolution in jurisprudence shifting significant economic regulatory power from the states to the federal government, thanks to an 1824 U.S. Supreme Court case, Gibbons v. Ogden.

Engineer and inventor Robert Fulton designed the Clermont, run by a company he organized in partnership with his wife’s uncle, Robert Livingston. In 1798, with steam power still theoretical, Livingston got an exclusive to sail steamships on rivers across New York. Livingston and the state extended that license in 1803—coincidentally, the year that Livingston, as President Thomas Jefferson’s emissary to France, negotiated the Louisiana Purchase. New York renewed his license in 1808, when company ships met a state demand to achieve at least five miles per hour under power. The shipping company grew. Within five years Fulton and Livingston had ships working six major rivers and Chesapeake Bay. Rivals were locking up franchises elsewhere.

In 1815, under its New York license, the Livingston-Fulton company subcontracted with Aaron Ogden. A former governor of New Jersey, Ogden had partnered with Georgia planter Thomas Gibbons on a shipping company. That scheme collapsed when, on his own, Gibbons began running between Elizabethtown, New Jersey, and New York City a competing steamship, Bellona. Gibbons had registered Bellona under the federal Coasting Act of 1793, which required licenses of all commercial vessels plying the country’s coasts. Ogden, citing his license under the monopoly awarded the Livingston-Fulton company, asked New York State courts to shut down Gibbons and Bellona. Both the Court of Chancery and the appeals court, then called the Court of Errors, agreed with Ogden that his sublicense gave him exclusive rights to call at New York ports, and that Gibbons had to stop sailing to those ports from New Jersey.

That precipitated a U.S. Supreme Court confrontation anyone who followed politics saw reaching well beyond shipping. With the American frontier pushing west and commerce between settlements there and the East becoming a national priority, an infrastructural frenzy had begun. Developers were digging canals. The federal government was paying to construct a 150-mile National Road between Cumberland, Maryland, and Wheeling, West Virginia. The ruling in the argument between Gibbons and Ogden would define the future not only of steamboat routes but interstate roads, canals, and technologies still gestating. As early as 1808 Jonathan Grout unsuccessfully asked Congress to give him a contract to establish a telegraph system; in 1815, Livingston’s brother-in-law, John Stevens, had gotten a license from New Jersey to run a railroad there, though it was 10 years before he had a line operating.

Technology aside, Gibbons v. Ogden was integral to the struggle, dating to the republic’s infancy, to define the extent to which states, in ratifying the Constitution, had yielded autonomy they had had under the Articles of Confederation. That debate’s nature was evident in the petitioners’ legal teams. Ogden had hired former New York State Attorneys General Thomas Emmet and Thomas Oakley. Gibbons was represented by Daniel Webster, chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, and sitting U.S. Attorney General William Wirt.

Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution authorizes Congress “to regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with Indian Tribes.” But until the high court took on the Gibbons/Ogden dispute, the justices never had been asked to define that authority.

In three days of oral argument, Ogden’s lawyers insisted that, as the New York courts had found, “commerce” meant little more than “trade,” and that the Constitution merely empowered Congress to set some rules about sale of goods by parties in one state to parties in another, with the proviso that the states had concurrent power with Washington. Webster and Wirt insisted the commerce clause meant much more, applying, by their lights, to all business contacts between parties in different states and, moreover, that only the federal government had the power to regulate such contacts.

The Webster-Wirt argument on behalf of Gibbons carried the day with flying colors. “Commerce, undoubtedly, is traffic, but it is something more: it is intercourse,” Chief Justice John Marshall wrote. “It describes the commercial intercourse between nations, and parts of nations, in all its branches, and is regulated by prescribing rules for carrying on that intercourse.” No single state could regulate a steamship plying between two states. Four of the five other Justices signed on to Marshall’s opinion. William Johnson did not, but he did agree with colleagues that New York could not stop Gibbons from running his steamboat from New Jersey to New York.

Marshall’s opinion went far further than handing Gibbons a win. Five years before, in McCulloch v. Maryland, Marshall had established that the federal government was meant to be very powerful (“Banking on Centralization,” August 2018), ruling that it had powers beyond those outlined in the Constitution if it needed those other powers to do its job. Now Marshall gave Washington something like a blank check to regulate broadly in the name of controlling interstate commerce. Congress could regulate not only commerce between states, he wrote, but also activities within a state “connected with” interstate commerce. Moreover, the chief justice decreed, that power “may be exercised to its utmost extent, and acknowledges no limitations, other than are prescribed in the Constitution.”

Congress listened. Gibbons v. Ogden paved the way for federal regulation of navigation and transportation and, in 1890, for the Sherman Act, written to bust trusts that dominating American industries ranging from oil to whiskey. In 1905 the justices upheld a federal attack on price fixing among Chicago meatpackers, reasoning that though the activity was all local, participants were links in an interstate chain connecting cattle farmers to the dinner table. The principle of federal power over interstate commerce eventually allowed Congress to ban child labor, to set minimum wages and other working conditions, and, in the Civil Rights Act of 1964, to outlaw race-based bias against customers even by small local businesses, on the rationale that they sold goods made out of state. Gibbons v. Ogden resonated nearly everywhere except in the litigants’ lives. By the time the court took the case in 1824, trencherman Gibbons was bedridden with the diabetes and obesity that killed him in 1826, and by 1829 business reversals had driven Ogden into debtor’s prison, languishing until the New Jersey legislature passed a law freeing him.