The term “ghost town” defines Hawkinsville more aptly than most other abandoned mining settlements. Almost no mention of it appears in the archives of Colorado newspapers, and long ago the old stage road in washed away, effectively sealing off the town from curious sightseers. Unlike other successful mining towns that boasted upward of a thousand residents at their peak, Hawkinsville’s population likely never climbed above 50. As best as can be determined, it never offered traditional town services like as a post office, hotel or saloon. Such were the province of Granite, a onetime county seat and Denver & Rio Grande Railway stop scarcely a mile to the southwest, whose population peaked at around 3,000. Even the first name of Hawkinsville’s founder has been lost to history. Yet, the tiny community reaped the rewards of a profitable gold mine not once, but twice.

In the spring of 1860 news of a rich strike of placer gold, dubbed the Georgia Bar, drew prospectors to this hilly stretch along the east bank of the Arkansas River midway between Leadville and Buena Vista. Initially undisturbed was the narrow gulch threaded by a clear-running stream in which Hawkinsville would pop up. For the time being the Georgia Bar and the brewing war back East absorbed locals’ attention.

In the wake of the Civil War a prospector by the last name of Hawkins staked the first claim along the brushy gulch some 2 miles above the Georgia Bar, defiantly registering it as the Yankee Blade. By 1867 the gulch had been thoroughly staked, and Hawkinsville had sprung into existence. Until flooding put it and neighboring mines out of commission, Hawkins’ own Blade proved the most lucrative claim. In a tally taken two decades later the mine was already credited with having produced ore worth more than $6 million in today’s dollars.

The district lay dormant until the early 1900s, when Hawkinsville recorded a brief revival as miners reworked the tailings, finding ore missed by the first wave of prospectors. This second boom lasted until about 1930 when the mines played out and were abandoned.

Jeff D. Eberle, the author of three overviews of Colorado ghost towns (Abandoned Western Colorado, Abandoned Northern Colorado and Abandoned Southern Colorado and the San Luis Valley), has visited Hawkinsville twice. He discovered it by accident after taking a wrong turn en route to another ghost town. “I realized I was following an old railroad bed when some narrow-gauge tracks actually appeared out of a mine shaft,” he recalls, “and I could see where they joined the road I was on.”

Eberle believes Hawkinsville miners extracted rough ore from the tunnels using small carts towed by mule and/or pushed by hand. From there a narrow-gauge steam engine would haul ore carts the half mile north to the Belle of Granite stamp mill in Low Pass Gulch. That mill processed ore for several area mines.

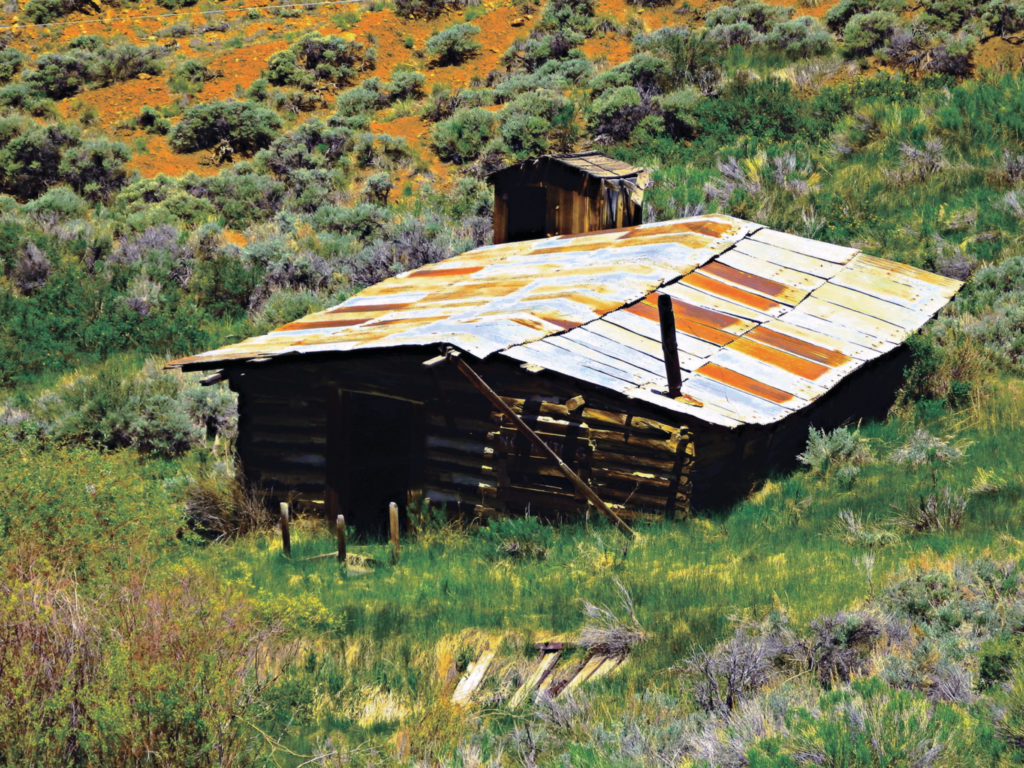

After making his discovery, Eberle spent hours poring over old newspapers only to find a handful of contemporary accounts of Hawkinsville. It is absent from most period maps. The 15 or so surviving structures in town appear very well constructed and remain intact. Eberle credits their longevity to the relatively arid climate in Hawkinsville. “The townsite itself,” he adds, “sits in a narrow canyon, offering additional protection from the elements, and, coupled with its difficult access, has resulted in preservation of the site. The only gold I found was on the glistening flanks of the cutthroat trout that swim in the creek, and the only resident left in town was a beaver lazily paddling across a pond without a care in the world.”