By the close of 1914, the French, British and German armies on the Western Front had gone to ground along a 400-mile front from the North Sea to the Swiss border. The possibility of mobile operations, such as turning movements, ceased to exist. A static siege-like contest dominated by the machine gun and the crushing power of big-gun artillery set in. As a result, breaking the enemy lines by direct infantry assault presented the only path to victory.

In order to make this possible, the “King of Battle”—field artillery—had to be liberally employed beforehand to weaken enemy defensive positions. As the conflict ground on, reliance upon the big guns increased. Artillery became the mainstay of French combat power, rising from 20 percent of the army in 1914 to 38 percent by war’s end. British artillery improvements were central to the assault techniques that proved so successful in 1918. Through sophisticated coordination of its artillery assets, Germany proved time after time that its guns could frustrate Allied attacks.

To counter the devastating effects of artillery, scout airplanes conducted aerial reconnaissance to locate enemy gun positions and troop concentrations so that cannon fire could be employed against them. By 1915, a second element was added to the air war: denying the enemy’s scout planes unfettered observation over the front lines. To achieve this goal, purpose-built pursuit aircraft (i.e., fighters), designed to shoot down enemy reconnaissance machines, entered the aerial arena. In 1917 the last part of the airpower equation was put in place: unit organizations, doctrine and weapons specifically designed to accommodate close air ground support needs.

The term close air support (CAS) encompasses bombing strikes, gunships delivering direct fire support to their footslogging compatriots and passive, but no less vital, reconnaissance for friendly ground units. Through 1915 the combatants still viewed the airplane’s primary function as a means of transmitting information to their infantry and artillery commands. As a result, the opposing air forces were organized into small units of six to 12 machines attached to corps and army headquarters to act in a reconnaissance role. That year saw the advent of machinegun-armed pursuit planes used to protect friendly scout aircraft and attack enemy reconnaissance planes. This rapid reorientation meant that the opportunity to develop CAS practices by any party was deferred to later in the war. After a full reordering of its air force, Germany seized upon the concept in 1917 and made it a viable battle tool.

The birth of Germany’s close air ground support came about with the demise of its original aerial philosophy, practiced from 1914 through most of 1916, of Sperre (blockade) patrols. This concept required that the German Fliegertruppe (air troops) create a continuous aerial barrier to Allied aircraft via constant patrols over German front lines. Not surprisingly, this “trench line in the sky” was doomed to fail due to the ease with which enemy aircraft could skirt over, below or around any German sky cordon. Use of this policy contributed to the forfeiture of aerial supremacy to the French and British over the battlefields of Verdun and the Somme, respectively, during 1916. That alarming situation drove the German high command to reorganize its air service on October 8, with the air force becoming the Luftstreitkräfte (army air service), led by Lt. Gen. Ernst von Hoeppner. Part of his brief was to assure more tactical cooperation between his command and the ground forces.

When Hoeppner took charge, the German air force had two components: Feldflieger Abteilungen (field flying detachments) and Artillerieflieger Abteilungen (artillery flying detachments). The former held six two-seater airplanes each—usually a mixture of different aircraft models—and was assigned to army and corps headquarters. Its purpose was to scout enemy positions, shoot down enemy reconnaissance planes and carry out bombing runs. The latter component consisted of four to six two-seater aircraft of different types, and was attached to army and corps headquarters or local artillery commands.

Achieving the conditions for proper close air support operations proved difficult. It was initially hoped that the new Jagdstaffeln (single-seat pursuit squadrons), first formed in August 1916, would supply the answer. More and more they were called upon to strafe enemy positions, communications and logistical points behind enemy lines in support of their own soldiers. But such duties were never popular among fighter pilots, since they brought the planes low to the ground, exposing them to every enemy soldier holding a gun, with pilot, fuel tank and radiator presenting vulnerable targets. As CAS went from casual adjunct in 1914-16 to regular requirement by 1917, new aircraft and tactics had to be developed.

The first concrete step the Germans took in implementing a permanent and cohesive close air support program occurred in early January 1917 when the air force disbanded three Kampfgeschwader (bomber wings) and designated their squadrons as Schutzstaffeln (Schusta)—“protection flights,” or escort squadrons. Each unit included one officer, 79 enlisted men, pilots and machine-gunners manning the six aircraft.

The new Schusta outfits were tasked with escorting the flying-detachment aircraft, protecting them from enemy interceptors. For training and better coordination purposes, these squadrons were posted at the same airfields where their wards were stationed. If attacked, the German reconnaissance plane would hightail it back to German lines while the two-seater escorts fought off the enemy and covered its retreat.

The original escort squadrons were equipped with Albatros DDK, Rumpler 4A13, Gotha Taube and Fokker M8 aircraft, all of which possessed performance characteristics and fighting abilities similar to the airplanes they were assigned to protect. But these C-type two-seaters were found to be insufficiently robust for ground-attack work. The army air service then turned to G-types, which boasted twin engines and multiple machine guns, but they proved too slow, heavy and unwieldy to adequately perform escort missions. After some experimentation, the Germans picked the Halberstadt CL.II and IV and the Hannover CL.II and III as their standard ground-support aircraft.

Designed to the new CL (light C-type) specification in 1917 to equip the escort squadrons, the Halberstadt CL.II was manufactured in considerable numbers. When it first came into use in the summer of 1917, it was primarily employed as a two-seat escort to accompany C-type reconnaissance and photographic planes. After May of that year, the CL.II’s mission changed to allow it to concentrate on direct close air support. Two events brought this about: the decimation of the Royal Flying Corps during “Bloody April”— wherein the British lost 245 aircraft for just 66 German losses—and the successful ground-support work of Captain Eduard W. Zorer’s Schusta 7 during the April 9–May 16 Battle of Arras.

With its distinctive communal cockpit occupied by both pilot and observer, the CL.II facilitated cooperation between the twoman crew and was admirably suited to its newfound CAS duty. The pilot had a first-class field of view, and the observer’s elevated gun ring enabled him to fire upward and forward. Armament consisted of a single machine gun plus anti-personnel grenades dropped by the observer from trays fitted outside the fuselage. These fast, nimble machines enjoyed much success in late summer 1917.

Although lightly built, the CL.II was sturdy due to its compact design. This small plane (for a two-seater) was driven by the ubiquitous 160-hp Mercedes D.III engine, which gave it a top speed of 112 mph, a maximum ceiling over 16,400 feet and a flight duration of three hours. Most of the fuselage was constructed of wood overlaid with thin plywood paneling. The wooden wings were fabric-covered, and the upper wing, with its pronounced sweep, gave the aircraft a rakish appearance.

The Halberstadt CL.IV, intended as a replacement for the CL.II, was very much like its predecessor and offered little improvement other than somewhat better maneuverability. Although it could be fitted with two fixed forward-firing machine guns, normally only one was employed.

Along with the Halberstadts, escort units also fielded Hannover CL.IIs and IIIas. With a span of only 40 feet, both were powered by an Argus As.III 180-hp engine. These two-seaters were unique in having a biplane tail, previously used only on multiengine aircraft. Its purpose was to reduce the tailplane/elevator span, giving the observer a wider field of fire. Compact and maneuverable, the Hannover CL.IIs and IIIs had good lateral control due to large balanced ailerons. More than 1,000 were built during the war.

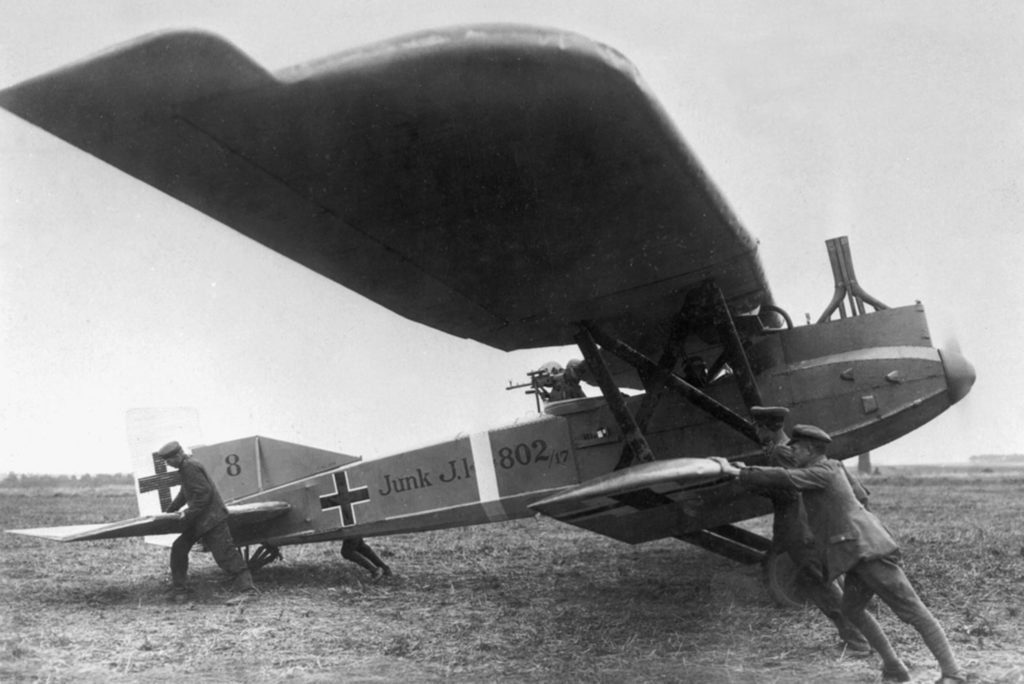

While the Halberstadt and Hannover light two-seaters relied primarily on their maneuverability to dodge groundfire, in 1917 the Germans introduced the J-type two-seaters, which protected their engines and crewmen with armor. The first such plane, the AEG J.I, was essentially an armor-plated AEG C.IV. Later that year, however, a more advanced close air support aircraft debuted: the Junkers J.I sesquiplane. Much of its fuselage was covered with corrugated alloy sheets rather than plain sheet metal. The 200-hp Benz engine and crew compartment were completely enclosed by 5mm chrome-nickel sheet steel, terminating in a solid bulkhead that protected the crew from astern. The only wooden part was a sturdy tailskid. With a speed of 95 mph, maximum altitude of 6,550 feet and two-hour flight duration, it proved to be the best CAS airplane of the war.

Flight controls were operated by direct linkage through a system of cranks and control push rods enclosed in the armored airframe, making the aircraft less vulnerable to groundfire. Although overweight and cumbersome on takeoff and landing, the J.I was immensely strong and well suited to its mission. All work was done at low altitude, with the observer reporting his findings via radio or message bag. Armament consisted of two synchronized, forward-firing Spandau machine guns and a Parabellum machine gun operated by the observer. The J.I’s late entry into the war and low production rate—only 227 were built—would prevent it from exerting a greater influence on the battlefield.

On April 24, 1917, Captain Zorer, commander of Schusta 7, was the first to use his escort plane in direct support of German infantry. As ground troops counterattacked British trenches along the Gavrelle-Roeux road near Arras, Zorer’s plane approached the battlefield at 1,300 feet, the turbulence from intense shellfire making it “dance back and forth, hanging first on one and then the other wing,” as he put it. Dropping to 60 feet, it was fired on by hundreds of British rifles as well as machine guns. Zorer, in the observer’s pit with his ring-mounted machine gun, and his pilot, using the forward-firing armament, sprayed the enemy trenches with 500 rounds before they were forced to retire when their engine was hit.

German ground-attack aircraft next did yeoman’s work during the Battle of Passchendaele in August 1917, when Schusta 18 supported the defending German Fourth Army in Flanders. Escorted by fighters, the CAS planes swooped in at 200 to 300 feet every day to attack British infantry and artillery positions with grenades and machine-gun fire.

During the fighting at Passchendaele, German aircrews developed and perfected the close air support tactics they would use for the rest of the war. German aircraft flew into the battle zone in groups of four or six in line-astern or line-abreast formation. (The former allowed them to better concentrate their fire and presented a smaller target to defenders. The latter helped fend off enemy pursuit planes attempting to engage at low altitudes.) The best height for attacking small targets such as trench systems, machine-gun posts and small bodies of infantry proved to be around 150 feet, while for larger targets—reserve infantry concentrations and artillery batteries—it was 1,200 to 1,500 feet.

As the German ground-support aircraft entered the battle zone, the flight leader used a flare pistol—firing different colored flares— to direct his command’s activities or warn of danger from the ground or the air. The formation looked for the signal lights or colored strips of cloth used by friendly troops to mark their positions. Once over enemy lines, the leading planes would seek out artillery sites, troop concentrations and machine-gun nests. After dropping their bombs, the flight would turn back to the German lines to reassemble, then return—in extended order—back over the enemy front to strafe and drop grenades on hostile infantry positions. When all the ammunition had been expended, the flight would rendezvous at a prearranged point and return to base.

During the last months of 1917, the German air service became the first to recognize that ground-support missions required a different pilot skill set than air-to-air combat or reconnaissance work. Accordingly, the Germans were the first to establish a subsidiary training program for their pilots.

The Battle of Cambrai brought home to the Germans the need for an effective, permanent ground-support air element. By the time the British offensive ground to a halt on December 7, 1917, 10 German ground-attack squadrons had entered the fray to aid their struggling infantry. The concentration of so many German CAS aircraft was an important factor in halting the British advance.

The ground-support formations were so successful that the British army convened an inquiry in January 1918 to examine the German success at Cambrai. It found that the significant number of German close air support aircraft strafing troops materially affected British morale to such an extent that the Tommies felt helpless, and that this was a significant factor in the success of the enemy counter attack.

Cambrai had shown what close air support could do when used en masse. For the German offensives of 1918, these aerial assets would be placed front and center.

Operation Michael was designed to smash the Allied armies and win the war. Thirty-eight CAS squadrons supported this massive offensive, which kicked off on March 21. According to a February 20 German high command memorandum governing the employment and duties of these units, they were tasked with “flying ahead of and carrying the [German] infantry along with them, keeping down the fire of the enemy’s infantry and barrage batteries.” The memo went on to declare that they could also immeasurably affect the assaulting forces, since the appearance of battle airplanes “affords visible proof to heavily engaged troops that the Higher Command is in close touch with the front, and is employing every means to support the fighting troops.” The objective of the ground-support formations was to shatter the enemy’s nerves and morale by constant attacks, and thus “dislocate traffic and inflict appreciable loss on the [enemy] reinforcements hastening up to the battlefield.” Used in great numbers, and at the decisive points of attack, the CAS units machine-gunned and bombed enemy frontline and rear areas, preventing the orderly movement of men, guns and supplies to and from the main fighting zones.

By 1918, the weapons employed by the German close air support branch had been standardized. The main machine gun for observers was the 7.92mm Parabellum Model 14, with a rate of fire of 700 rounds per minute. The Maxim Model 08 and 08/15 were also widely used. For bombing missions, a 100-pound bomb or four 25-pound bombs were carried in an internal rack in the gunner’s cockpit. In 1917 Halberstadt and Hannover crews began using the stick hand grenade, commonly called the “potato masher.” Later they began to bundle six of these together into the Teufel Faust (devil’s fist). These were very effective, but had to be tossed from the plane at 140 feet or less due to the short 5½-second fuse delay. They could inflict serious damage within an 80-foot radius.

Due to their achievements in Operation Michael, the ground support squadrons were renamed Schlachtstaffeln (attack squadrons) on March 27. From April through July, the German army launched four more large-scale offensives. During each assault the attack squadrons formed the spearhead in ever larger formations: Schlachtgruppen (a group of two or more attack flights) and Schlachtgeschwader (an air wing composed of four-plus attack flights). But as the year entered its third quarter, the German air service found itself outnumbered, short on fuel and spare parts and unable to make good the losses of experienced aircrews suffered daily over the front.

The brutal battles that took place in late 1918—Amiens, St. Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne—saw the attack squadrons in the thick of the fight. Some notable victories, such as the one on September 29 in the Argonne Forest against the Americans, were achieved. With German ground units about to be overrun by masses of U.S. troops, Schlachtgruppe 3 came to the rescue and caused the attackers to, in the words of a German army officer present, scatter “in wild flight” under the hail of the diving and swooping planes.

With the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 and the peace that followed, the belligerent nations all but ignored the doctrine and tactics of close air support. However, a few, like former German naval aviator Gotthard Sachsenberg, who flew combat missions in the Baltic states with the Freikorps in 1919, worked to perfect the ground-support techniques established during World War I. Sachsenberg’s writings on the subject would be used by those who 20 years later plunged humanity into a new global conflict.

Baltimore-based attorney Arnold Blumberg regularly contributes to a number of journals and magazines on military history topics. He recommends for further reading: Schlachtflieger! Germany and the Origins of Air/Ground Support 1916-1918, by Rick Duiven and Dan-San Abbott; The First Air War, by Lee Kennett; and German Aircraft of the First World War, by Peter Gray and Owen Thetford.

Originally published in the November 2014 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.