When it comes to creating extreme aircraft—both good and bad—it’s difficult to outdo Nazi Germany. The Reichsluftfahrtministerium (Ministry of Aviation, or RLM) was apparently willing to invest in any aeronautical idea, regardless of how bizarre. For their part, German engineers happily obliged by coming up with some of the most outlandish aircraft ever conceived. Arado’s little Ar-231 floatplane, designed to be transported and launched from a submarine, has to come near the top of the list.

The concept behind the design, meant to fulfill a very stringent navy requirement for a spotter plane, could in itself be characterized as extreme. Aircraft operating from warships generally have to be compact, but in this case the airplane was to operate from a submarine that hadn’t even been built yet, the Type XI Unterseekreuzer. Designed in 1939, the 377-foot-long U-cruiser would have been the second largest sub in the world, after the Japanese floatplane-carrying I-400 class.

Unlike its Japanese counterparts, however, the Type XI would have lacked launching catapults. In addition, the Japanese subs had horizontal hangars, allowing their aircraft to move directly onto the catapult for launching. The U-cruiser, in contrast, was designed to store its aircraft in a vertical tube just forward of the conning tower. The floatplane was to be stowed in a nose-down attitude to protect the airframe from dripping oil and fuel. When needed, it would be hoisted onto the deck with a crane, assembled, lowered over the side and then flown off the water.

As with several of Germany’s other ambitious naval programs, construction of the Type XI U-cruisers was cancelled at the beginning of World War II in order to conserve raw materials for more vital weapons production. For unknown reasons, though, Ar-231 development continued. The first prototype of Arado’s little scout made its maiden flight on July 25, 1940, nearly a year after construction of the vessels from which it was meant to operate ceased.

In most respects the Ar-231’s design was fairly conventional for a single-engine, single-seat, twin-float parasol monoplane. The tail fin was unusually low and the elevator stuck out behind the rudder, both features dictated by the sub’s limited stowage space. What set it jarringly apart from the crowd, however, was its wing configuration. In an effort to facilitate folding, the designers mounted the center section at an 11.5-degree angle, with the left wing higher than the right. In addition, the left wing was rigged with a noticeable dihedral angle, whereas the right wing was almost flat. The wings were deliberately designed that way in order to allow one to fold beneath the other to save space.

Arado’s engineers went out of their way to produce an airplane that would be easy to assemble. In fact, the Ar-231 reportedly could be deployed in as little as six minutes. The resulting floatplane, however, looked as though it had been assembled incorrectly or had been involved in a nasty accident.

Powered by a 160-hp Hirth engine, the Ar-231 had a wingspan of 33 feet, was 25 feet long and weighed only 2,200 pounds. Maximum speed was listed as 106 mph and range as 311 miles. Since the floatplane had a hard time getting airborne with a full fuel load in normal sea conditions, range under actual operational conditions would undoubtedly have been far less.

Flight testing continued through 1941, and six prototypes were produced. As might be expected, the floatplane’s handling characteristics, both in the air and on the water, were less than stellar. The Ar-231 proved to be unstable, underpowered and flimsy. It was incapable of taking off in anything rougher than the smoothest sea conditions unless a few weighty items were removed…such as the radio and much of the fuel!

In spite of its shortcomings, the Ar-231 got a reprieve from oblivion in May 1942, when two of the six prototypes went to sea in the new surface raider Stier. The proven and much-preferred Arado Ar-196 floatplane was too large to fit into the converted cargo ship’s hatches, leaving the Ar-231 as the only available alternative. They proved so useless, however, that Stier’s captain, Horst Gerlach, regretted taking them along. When Stier fell victim to its last prey, the Liberty ship Stephen Hopkins, on September 27, 1942, both Arados went down with it.

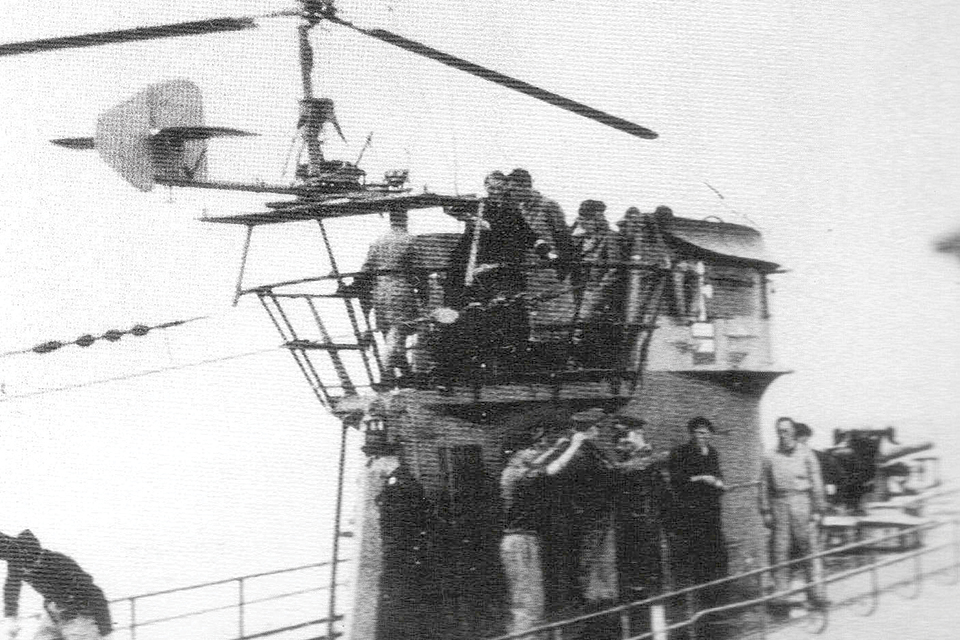

No U-boat ever took an Ar-231 to sea. Undeterred, the RLM came up with an even more improbable alternative to serve as the submariner’s aerial observation platform: the Focke-Achgelis Fa-330. The tiny 150-pound gyrocopter was designed to be towed behind a surfaced submarine at the end of a 500-foot tether, like a rotary-wing kite. The idea was that one of the crew would go up in the little helicopter to scan the horizon for potential victims. If he spotted an enemy ship or aircraft, the tether would be immediately cut and the sub would crash-dive. In a scene reminiscent of the fate of the Zeppelin observer in Howard Hughes’ famous film Hell’s Angels, the hapless U-boat lookout would be left to auto-rotate into the sea, to be picked up later by his comrades, or not, as fortune decreed.

Not surprisingly, the U-boat crews exhibited no more enthusiasm for the Fa-330 than they had for the Ar-231. Fortunately for them, new developments in air and surface search radar made all those aerial observation posts redundant.

This article originally appeared in the November 2018 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe here!