By November 1943, the residents of Mexia, a town in the Texas hill country, had been putting up with war for nearly two years. They had endured the hardships of rationing, meat and gasoline shortages, and heartache for loved ones fighting overseas. Then one November day trains arrived from the East Coast, and suddenly hordes of enemy soldiers were marching into their very midst.

That afternoon, townspeople lined up along Railroad Street to stare awestruck at the seemingly endless stream of German soldiers. These 3,250 sunburned, battle-hardened veterans of the fighting in North Africa wore the khaki desert-style uni-forms, large billed cloth caps, and goggles that symbolized Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s infamous Afrika Korps. Their ranks soon stretched three miles down Tehuacana Highway as the soldiers walked to the newly constructed prisoner of war camp intended to house them for the duration. “We were a town of only 6,000 people,” recalled a longtime Mexia resident, “and we had just seen our population increased by 50 percent—and they were foreigners on top of it!”

That afternoon, townspeople lined up along Railroad Street to stare awestruck at the seemingly endless stream of German soldiers. These 3,250 sunburned, battle-hardened veterans of the fighting in North Africa wore the khaki desert-style uni-forms, large billed cloth caps, and goggles that symbolized Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s infamous Afrika Korps. Their ranks soon stretched three miles down Tehuacana Highway as the soldiers walked to the newly constructed prisoner of war camp intended to house them for the duration. “We were a town of only 6,000 people,” recalled a longtime Mexia resident, “and we had just seen our population increased by 50 percent—and they were foreigners on top of it!”

Similar scenes occurred that year in dozens of small communities throughout the American South and Southwest. In Concordia, Kansas, the train arrived after dark and the POWs disembarked under bright lights installed by the army that lit up curious throngs of onlookers like a “circus day,” as a newspaper reporter observed. At Crossville, Tennessee, noted Beverly Smith of American Magazine, the new arrivals “glance about with a puzzled expression. For them, the Axis glory trail has led to Main Street, U.S.A, opposite the ‘Last Chance Café,’ the filling station, Cole’s Cash Store, and ‘New and Used Shoe Repairs while U Wait.’”

Enemy POWs would eventually fill more than 900 camps in 46 states, plus Alaska. By official count, these installations would house no fewer than 435,788 men who had fought the Allies—the vast majority from the German military. There were also 51,455 Italians and 5,435 Japanese held in the United States, but the Americans and British confronted and thus captured far more Germans on the battlefields of North Africa, Italy, and Western Europe. As a result, the camps would bring 378,898 of these men into everyday contact—and sometimes conflict—with millions of Americans on the home front.

It was the first time that substantial numbers of foreign POWs were held on American soil. During World War I, only 1,346 German POWs—mostly sailors—had been interned here. As of August 1942, only 65 German prisoners were being held in the United States. Britain, however, was bulging with 273,000 Germans and Italians. Unable to meet food and housing requirements set by the 1929 Geneva Convention and with an eye on the looming North Africa invasion, Britain convinced the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff to begin taking prisoners off its hands—150,000 to start. So great was the influx by mid-1943 that when Prime Minister Winston Churchill headed to Washington to discuss the Italian Campaign, he shared the Queen Mary with several thousand Axis POWs.

It was the first time that substantial numbers of foreign POWs were held on American soil. During World War I, only 1,346 German POWs—mostly sailors—had been interned here. As of August 1942, only 65 German prisoners were being held in the United States. Britain, however, was bulging with 273,000 Germans and Italians. Unable to meet food and housing requirements set by the 1929 Geneva Convention and with an eye on the looming North Africa invasion, Britain convinced the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff to begin taking prisoners off its hands—150,000 to start. So great was the influx by mid-1943 that when Prime Minister Winston Churchill headed to Washington to discuss the Italian Campaign, he shared the Queen Mary with several thousand Axis POWs.

The United States was completely unprepared to deal with POWs on this scale. As the nation was gearing up its war industry and training troops, officials had to figure out how to house, feed, and secure incoming POWs. Under a crash program launched by the army’s Prisoner of War Division in September 1942, parts of existing army installations were converted, enemy alien internment camps appropriated, Depression-era Civilian Conservation Corps camps rehabilitated, and new facilities built from scratch. By 1943, housing was ready at 33 camps for some 78,000 prisoners.

Camp construction and operation adhered strictly to Geneva Convention specifications. The first of the 155 main camps, each typically housing 3,000 or so prisoners, were established in the South and Southwest—dry, mild climates where the prisoners would be comfortable while the War Department saved on heating costs. Comparable to the space alloted to U.S. Army troops, each captive non-commissioned officer and private soldier received 40 square feet of lodging, and officers received 125 square feet. If POWs had to be temporarily housed in tents, so did their American guards—even if barracks sat empty nearby. Meals also equaled those fed to American troops stateside. The policies were both principled and pragmatic: the Joint Chiefs hoped the Germans would follow suit in the treatment of their 94,000 American POWs.

In addition to getting the camps ready, the army had to prepare nearby communities for the arrival of thousands of enemy prisoners. Army officials often met ahead of time with local officials, reporters, and civic groups to reassure them of security safeguards, with promises of a boost to the local economy to help overcome reluctance. Construction of prisoner compounds would bring in government money for local builders. Army personnel would spend money on Main Street, and POWs could provide labor on farms and in factories. These benefits proved attractive; a few towns, such as Hearne, Texas, even campaigned to have a camp built nearby.

Still, opposition persisted throughout the war. Many communities rankled at having Germans in close proximity while sons and husbands were fighting fascism overseas. The director of the Prisoner of War Division, Colonel Francis E. Howard, told one magazine reporter that out of hundreds of letters he received each week, “about half echo the thoughts of one man who advised: ‘Put them in Death Valley, chuck in a side of beef, and let them starve to death.’”

Still, opposition persisted throughout the war. Many communities rankled at having Germans in close proximity while sons and husbands were fighting fascism overseas. The director of the Prisoner of War Division, Colonel Francis E. Howard, told one magazine reporter that out of hundreds of letters he received each week, “about half echo the thoughts of one man who advised: ‘Put them in Death Valley, chuck in a side of beef, and let them starve to death.’”

On occasion, GIs assigned to camps took the brunt of frustrations. First Lieutenant William A. Ward, a medical supply officer at Camp Brady, Texas, recalled “an unnerving experience” while escorting a group of about 30 POWs to Camp Polk, Louisiana: “While waiting for our military bus, I bought Cokes for all the guards and POWs. To my shock, the woman behind the counter at the general store went wild; she yelled and cursed, accused me of sympathy for the enemy, and damn near physically hit me.”

Resentment was heightened by the perception that the government treated POWs too well. Since they ate as well as their American guards—including fresh fruit and ample animal protein—prisoners sometimes ate better than American civilians, whose meat was rationed. The typical POW gained weight, and wrote home to discourage family members from sending their own sorely needed food.

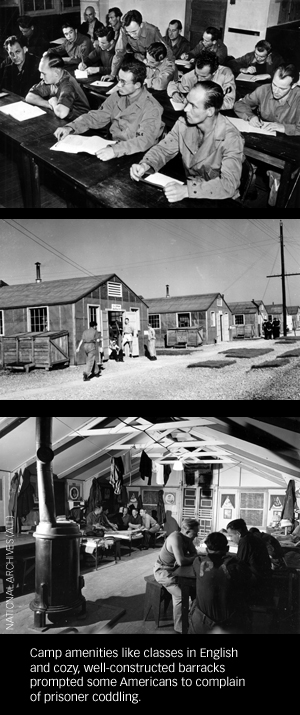

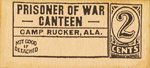

Though hastily constructed and roughly finished, prisoner barracks were contemptuously referred to as the Fritz Ritz by some Americans. In truth, POWs could enjoy canteens that sold beer for a dime a bottle, concerts by camp orchestras and glee clubs, soccer fields and other recreational facilities, libraries, and even college courses accredited by Germany’s education ministry. One prisoner wrote home that after the rigors of combat, imprisonment “was like a rest-cure.”

As the war ground on, charges of “coddling” erupted in Congress and the press, where headlines such as “Our Pampered War Prisoners” were not uncommon. The army cited the need to set an example for German captors of American servicemen, and insisted that word of “the good life” behind the wire in the U.S. actually reached German soldiers still on the battlefield, leading ever-larger numbers to surrender.

Comfortable camp life also discouraged attempts at escape. As Josef Krumbachner, a Wehrmacht artillery officer captured during the 1944 Allied invasion of Europe, wrote of his experience at Camp Como, Mississippi, “Some of us thought it foolish to escape from a place where we were enjoying relative freedom and good care to return to a Germany where death, hunger, and other dangers were still the rule of the day.” The rate of escape attempts proved no higher than that at federal penitentiaries; the army recorded 2,222 attempts, less than one percent. The POWs who did try to break out typically had mundane reasons: boredom, depression, or a Dear John letter. No acts of sabotage were recorded; the worst crime committed by escapees was car theft.

The most sensational mass break-out occurred in December 1944, when 25 U-boat officers and crewmen scrambled out of Papago Park, Arizona, through a 178-foot tunnel. They were all recaptured within five weeks. (See “The Not-So-Great Escape,” December 2007, available online.) Infantry Sergeant Reinhold Pabel was far more successful after he slipped out of Camp Grant, Illinois, in 1945. He took with him a magazine article by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover on tracking escaped POWs, and used it as a handbook to avoid mistakes. Calling himself Phillip Brick, he lost himself in Chicago and worked at a number of odd jobs. When the FBI finally caught up with him in 1953, he was married, expecting his second child, and running a secondhand bookstore. Pabel was deported to Germany, but allowed back a year later to rejoin his family in the life he had made for himself.

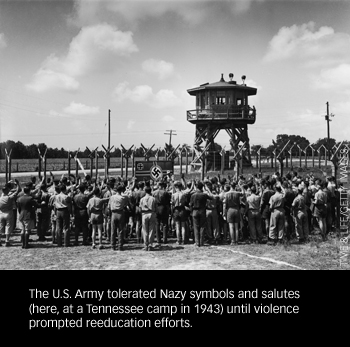

As concern over prisoner escape ebbed, camp officials and nearby communities were increasingly mindful of Nazi domination in many compounds. Anyone in German uniform was classified as a German POW upon capture, so most camps comprised a volatile political, religious, national, and ethnic mix that reflected the polyglot nature of the German army. There were common criminals and political dissidents along with Poles, Czechs, Dutch, Russians, and other nationalities conscripted from occupied regions. Less than 20 percent of POWs were hardcore Nazis, but the most hardcore Hitlerites—captured in North Africa—were the first to arrive stateside, and possessed the discipline and organization to establish their insidious brand of order within the camps.

As concern over prisoner escape ebbed, camp officials and nearby communities were increasingly mindful of Nazi domination in many compounds. Anyone in German uniform was classified as a German POW upon capture, so most camps comprised a volatile political, religious, national, and ethnic mix that reflected the polyglot nature of the German army. There were common criminals and political dissidents along with Poles, Czechs, Dutch, Russians, and other nationalities conscripted from occupied regions. Less than 20 percent of POWs were hardcore Nazis, but the most hardcore Hitlerites—captured in North Africa—were the first to arrive stateside, and possessed the discipline and organization to establish their insidious brand of order within the camps.

With the army’s approval for much of the war, German officers ran the typical camp’s internal affairs. They appointed the prisoner spokesmen, and controlled library and educational program content. Books banned by Hitler were quietly removed from library shelves; news of German defeats was silenced as enemy propaganda. As long as a camp ran with the Germans’ vaunted efficiency, many American commandants were happy to look the other way—at least until violence erupted. Though prisoners could declare themselves anti-Nazis and be sent to one of three segregated camps, most mouths were kept shut by rumors that spies sent lists back to the Gestapo for reprisals against traitors’ families. Any POW whispering anti-Nazi views or suspected of cooperating with the Americans risked trial by a kangaroo court. A common sentence was a visit by the “Holy Ghost,” a euphemism for a severe beating. At least seven POWs were murdered, and scores were prompted to commit suicide.

In 1944, American officials belatedly began moving known Nazis into separate facilities. In hopes of stemming violence and preparing POWs for a democratic postwar Germany, officials also launched a secret and controversial attempt at reeducation. Though in violation of the Geneva Convention, the Intellectual Diversion Program sought to indoctrinate German POWs with lessons in democracy through printed materials, films, and classes.

In 1944, American officials belatedly began moving known Nazis into separate facilities. In hopes of stemming violence and preparing POWs for a democratic postwar Germany, officials also launched a secret and controversial attempt at reeducation. Though in violation of the Geneva Convention, the Intellectual Diversion Program sought to indoctrinate German POWs with lessons in democracy through printed materials, films, and classes.

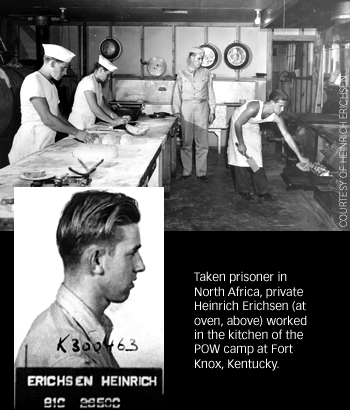

But the most effective and popular policy put the POWs to work, far outdoing classroom efforts as an introduction to the American way of life. Prisoners were responsible for camp upkeep and maintenance, and under the Geneva Convention enlisted men could also be required to work—as long as conditions were safe and the work had “no direct relation with war operations.” In addition to the 10-cent daily allowance prisoners received for personal needs, the War Department paid workers 80 cents a day from the wages collected from employers—roughly equal to an American enlisted man’s starting monthly pay. The War Department used the rest of the wages to defray the cost of transporting, housing, securing, and feeding the prisoners. Some camps even turned a profit; the prisoners at Pine Camp, New York, earned an additional $120,708.67 after covering the government’s facility costs.

At first, POWs were assigned to conservation projects, road maintenance, and utility work at military installations or hospitals. During the summer of 1943, private employers were invited to contract prisoner labor. Germans were soon cutting timber, laboring in foundries and open pit mines, and working in food-processing plants. Before word spread of the mass killing of Jews in Europe, some POWs even packed meat at a kosher plant in New Jersey. But more than half provided sorely needed agricultural manpower, augmenting a workforce drained by the armed forces and higher-paying war industries. POWs dug peanuts in Georgia and potatoes in Maine, picked tomatoes in Indiana and cotton in Texas, gathered corn in Illinois, and harvested sugar cane in Louisiana.

Behind the scenes, bureaucrats in Washington, D.C., worked through troublesome policy issues raised by the program. Unions objected to prisoner labor contracts that under-cut ; this prompted the government to verify that American workers were unavailable, and to charge employers the prevailing labor wage in each locality. But the government balked when some unions demanded 25 cent in dues from each POW’s weekly wages. Perhaps the most vexing problem was how to interpret the Geneva Convention ban on prisoners laboring directly for the war effort. Washington eventually approved putting POWs on a Jeep assembly line, with the rationale that the vehicles were not destined for combat.

There were no Geneva Convention articles to give the government pause when camp leaders tried to hinder the work program with strikes or slowdowns. The War Department cracked down with a “no work, no eat” policy. Malingerers received a daily diet of 18 ounces of bread plus unlimited water, and were usually back on the job in short order. A new pay system instituted in the spring of 1944 permitted the War Department to pay slackers less and reward hard workers with up to $1.20 a day.

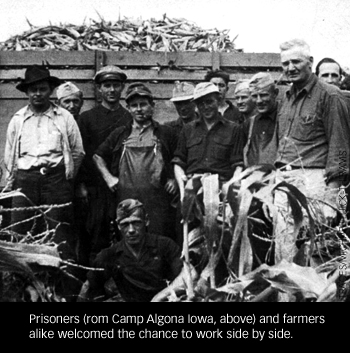

Most prisoners, however, were eager to get out of camp, earn a bit of money, and interact with Americans. By the end of the war, nearly 96 percent of enlisted men were participating in the labor program, along with 45 percent of non-commissioned officers and 7 percent of commissioned officers. Their labor proved invaluable to numerous ranchers and farmers who could not have stayed in business otherwise. A rancher near McAlester, Oklahoma, contracted 40 prisoners to work his 3,000 acres after all his employees quit for better-paying war industry jobs. “They’ve been our salvation,” he said.

Most prisoners, however, were eager to get out of camp, earn a bit of money, and interact with Americans. By the end of the war, nearly 96 percent of enlisted men were participating in the labor program, along with 45 percent of non-commissioned officers and 7 percent of commissioned officers. Their labor proved invaluable to numerous ranchers and farmers who could not have stayed in business otherwise. A rancher near McAlester, Oklahoma, contracted 40 prisoners to work his 3,000 acres after all his employees quit for better-paying war industry jobs. “They’ve been our salvation,” he said.

Luftwaffe lieutenant Guenther Oswald was one of the few officers at Camp Trinidad, Colorado, that volunteered for work. He remembered harvesting sugar beets for a farmer who promised to take the POWs to his home if they would sing for his German-born grandmother. “We sang,” Oswald recalled, “the old lady cried, and we got lots of food and cigarettes.”

To make prisoner labor available where it was most needed, the army began by adding 511 satellites to the 155 main camps, each temporarily housing 250 to 750 POWs in all manner of improvised facilities—hotels, schools, courthouses, fairgrounds, even circus tents and an abandoned insane asylum. Branch camps also brought POWs into much closer contact with civilians, vividly illustrated in Wisconsin’s 38 branch camps. A third of the state’s residents were of German ancestry, many recent enough to have relatives fighting on both sides in Europe. Robert Lawrenz recalled his father answering the door of their Sheboygan home and finding his brother standing there in a POW uniform.

The army’s main concern about the work program was fraternization between POWs and female civilians, and with good reason. Illicit romances—or rumors of them—were common at factories, where German prisoners and American women often worked side by side. At Camp Cooke, California, one German took advantage of his bus driving assignment by parking in a remote area to canoodle with a fellow employee. Perhaps the most extreme instance was a Wisconsin branch camp where local teenage girls slipped past lax security to cavort with the prisoners.

Even so, security was far from rigorous at branch camps and work sites. Army regulations initially called for one guard for every ten POWs on the job, and the requirement loosened further as the war in Europe neared an end. It became common to find one guard—or none at all—supervising a field full of prisoners picking cotton or harvesting sugar beets. Stories were legion of guards sleeping on the job, or asking prisoners to retrieve weapons left in the field. “Since many of the GIs enjoyed an active night life,” recalled Paul Lohmann, a POW working out of Fort Dix, New Jersey, “they were always tired during the day. We hid them, so that they could sleep during the day. We warned them when the sergeant of the guard was approaching to check on them.”

An extraordinary level of trust marked some relationships between POWs and their employers as well. A Kansas family likened the Germans to their “local farm boys,” trusting them around their children and even sending one out on a pony to pick up their first-grade daughter from school. Another farmer went so far as to let one of his workers go off hunting unattended with a shotgun in the pasture. His trust was rewarded when the POW brought back 10 rabbits for the stew pot. Despite official warnings about fraternization, Germans were frequently invited to the dining room table for a meal. An army representative in Peabody, Kansas, felt compelled to personally caution farm wives about mending clothes for POW workers and baking them cakes and cookies.

An extraordinary level of trust marked some relationships between POWs and their employers as well. A Kansas family likened the Germans to their “local farm boys,” trusting them around their children and even sending one out on a pony to pick up their first-grade daughter from school. Another farmer went so far as to let one of his workers go off hunting unattended with a shotgun in the pasture. His trust was rewarded when the POW brought back 10 rabbits for the stew pot. Despite official warnings about fraternization, Germans were frequently invited to the dining room table for a meal. An army representative in Peabody, Kansas, felt compelled to personally caution farm wives about mending clothes for POW workers and baking them cakes and cookies.

Many POWs developed friendships with their farm employers, some of which persisted into peacetime. John Hauser recalls how his father Dawson, an apple grower in Bayfield, Wisconsin, befriended a POW worker named Joseph Ruelick. After the war, Dawson Hauser sent money to Ruelick to help him and his family recover from the war. In the 1970s, Ruelick brought his family to meet his former employer and benefactor, but sadly found him confined to a nursing home by Alzheimer’s, unable to remember their unusual friendship.

By the end of the war, German prisoners had been housed at more than 900 facilities scattered across the nation, leaving an indelible mark on the home front. The labor program, in addition to keeping POWs mostly out of trouble, provided an infusion of some 200,000 workers that helped alleviate the severe labor shortage in the United States and helped free thousands of Americans to serve in the the armed forces and work in the war industries. The prisoners became so essential to agriculture that for the 1945 harvest, President Harry S. Truman gave in to pressure from growers and delayed the repatriation of Germans who had been contracted out in sugar beets, cotton, and pulpwood.

By the end of the war, German prisoners had been housed at more than 900 facilities scattered across the nation, leaving an indelible mark on the home front. The labor program, in addition to keeping POWs mostly out of trouble, provided an infusion of some 200,000 workers that helped alleviate the severe labor shortage in the United States and helped free thousands of Americans to serve in the the armed forces and work in the war industries. The prisoners became so essential to agriculture that for the 1945 harvest, President Harry S. Truman gave in to pressure from growers and delayed the repatriation of Germans who had been contracted out in sugar beets, cotton, and pulpwood.

The process of repatriating POWs and shutting down the camps was done for the most part by the end of 1946, leaving something of a void in the neighboring communities. One such town was Kaufman, Texas, a satellite of the main camp near Mexia, where battle-hardened Afrika Korps POWs had arrived to an audience of awestruck locals just two years before. The local newspaper reported in November 1945 that the women’s clubs had decided to stage a farewell dance for the departing American guards at the nearby camp. They had the sense of history to also invite the Germans, whose presence had been the cause of it all.

Ronald H. Bailey has written four books on World War II, including Prisoners of War. He remembers sleeping at Camp Perry, Ohio, as a 16-year-old attending Buckeye Boys State—the American Legion’s mock state government—and having no idea that six years earlier those same rundown barracks had housed German prisoners of war.