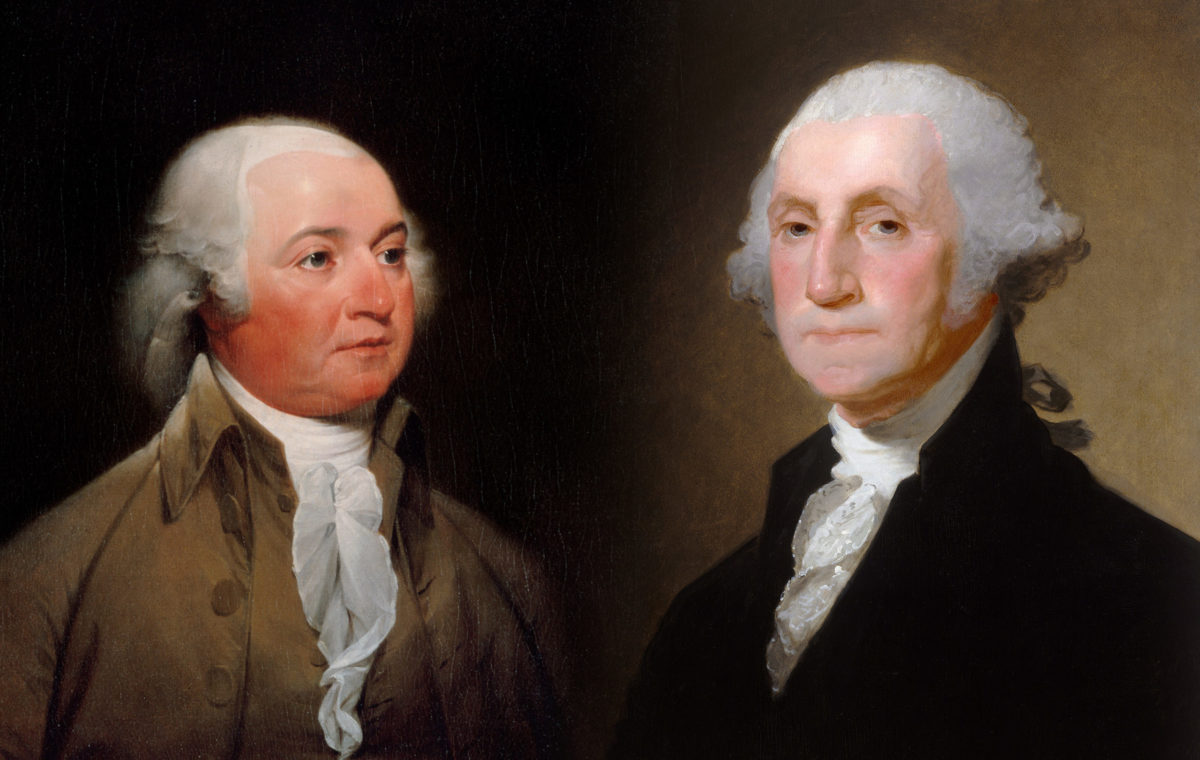

George Washington’s unexpected death on Dec. 14, 1799, shocked the country and its current president. In his official message of mourning to the Senate, John Adams struck a personal note, saying, “I feel myself alone, bereaved by my lost brother.”

The story of those titans’ relationship is more complicated than his statement suggests, but surely Adams did see Washington fraternally, struggling as they had for a common cause. Both exceptional men of their generation — Adams was three years Washington’s junior — they hungered for fame across the ages. Devout patriots, they laid their lives on the line for independence. Each was a paragon of integrity animated by a strong sense of honor and possessed of similar political outlooks. Each believed in a strong Union and an energetic national government, and both doubted humanity’s beneficence, reflexively distrusting philosophies that presumed man’s natural goodness. These commonalities set Adams and Washington up for decades of association and fruitful, if sometimes conflicted, interaction.

John Adams’ American Idol

Certainly, the plump, vertically challenged Adams felt respect, loyalty and awe for the towering, muscular Virginian who was able to command a room in a way that Adams never could. He and Washington seem to have first directly engaged one another in Philadelphia as participants in the First Continental Congress, on Sept. 28, 1774.

Adams had recently recorded in his journal, “Coll. Washington made the most eloquent Speech at the Virginia Convention that ever was made. Says he, ‘I will raise 1000 Men, subsist them at my own Expence, and march myself at their Head for the Relief of Boston.’”

No such thing ever happened, but in embracing the rumor Adams betrayed a disposition to hold Washington in high regard.

At the Second Continental Congress in 1775, Adams nominated Washington to be commander in chief of the nascent Continental Army, thrusting the other man into a spotlight whose glare would follow him for the rest of his life. By this time, Washington clearly had impressed Adams. Wearing a brand-new military uniform, Washington chaired four congressional committees, including one preparing rules and regulations governing the army.

Of the military man’s performance, Adams wrote, “by his great experience and ability in military matters, [Washington] is of much service to us …. A gentleman of one of the first fortunes on the continent, leaving his delicious retirement, his family and friends, sacrificing his ease, and hazarding all in the cause of his country.”

Saving George Washington

After the Conway Cabal of 1777-78, a short-lived attempt by some congressmen and high-ranking officers to replace Washington as commander in chief with Gen. Horatio Gates, critics questioned Adams’s loyalty to Washington because of some of his comments and connections to Dr. Benjamin Rush and others who were involved in the cabal.

Gen. Henry Knox, a Washington man to the bone, called on Adams at home in Braintree, Massachusetts. Adams was about to sail to France on a diplomatic mission. Knox wanted assurance that Adams would not be bad-mouthing Washington to Europeans. Adams told Knox he held the general to be “a perfectly honest Man, with an amiable and excellent heart, and the most important Character at that time among Us, for he was the Center of our Union.” Adams declared that out of principle and affection, public and private, he would do “his utmost to support his character at all times and in all places.”

Elected Washington’s vice president, Adams sought to be a perfectly loyal No. 2.

“Were I blessed with powers to do justice to his character, it would be impossible to increase the confidence or affection of his country, or make the smallest addition to his glory,” he told newly elected members of the Senate. “Where shall we find one, whose commanding talents and virtues … have so completely united all hearts and voices in his favor?”

As presiding officer of that body Adams cast 31 tie-breaking votes, always supporting the administration position.

When Adams became president and war with France threatened, he nominated — and the Senate unanimously confirmed — Washington to be “Lieutenant General and Commander in Chief of all the Armies raised or to be raised for the service of the United States.”

Adams wrote Washington: “If it had been in my power to nominate you to be the president of the United States, I should have done it with less hesitation and more pleasure.”

After Washington’s death, Adams acknowledged to his dear friend Rush that he both “revered” and “loved” Washington.

John Adams’ Green-Eyed Monster

But for all his admiration and affection, Adams felt a complicated knot of emotions, including envy and resentment, toward Washington. That knot is as much a part of the story of these two men as Adams’s respect, loyalty and awe. Adams was self-reflective enough to acknowledge his raging vanity. He confessed as a young man, “Vanity is my cardinal vice and cardinal folly.”

Alexander Hamilton diagnosed Adams as suffering from the grip of “disgusting egotism,” and Adams never did succeed in throttling that egotism or in finding a spot in his heart for any in his circle who outshone him. Forever feeling underappreciated, Adams lamented to Rush about “the eternal puffing and trumpeting of Washington and Franklin and the incessant abuse of the real Fathers of the Country,” in whose ranks he of course included himself.

Resentment and envy of Washington were a leitmotif for Adams. Almost immediately upon seeing Washington made commander in chief, Adams seemed to mope about the glamour that enveloped the new hero. When pomp and ceremony marked Washington’s departure from Philadelphia for Boston to take command, Adams wrote to wife Abigail, “Such is the Pride and Pomp of War. I, poor Creature, worn out with scribbling, for my Bread and my Liberty, low in Spirits and weak in Health, must leave others to wear the Lawrells which I have sown; others, to eat the Bread which I have earned.”

Washington’s victories at Trenton and Princeton kindled yet more adulation — and more envy on Adams’s part. Some in Congress were “disposed to idolize an image which their own hands have molded,” he declared. “I speak here of the superstitious veneration that is sometimes paid to General Washington. Although I honor him for his good qualities, yet in this house I feel myself his superior. In private life I shall always acknowledge that he is mine.”

After the Battle of Saratoga, Adams rejoiced that Gates and not Washington had whipped Gen. John Burgoyne’s redcoats.

“If it had been [Washington], idolatry and adulation would have been unbounded; so excessive as to endanger our liberties,” Adams seethed. “We can allow a certain citizen to be wise, virtuous and good without thinking him a deity or a savior.”

Correspondingly, Washington’s failure to keep the British from taking Philadelphia brought further fulmination.

“Oh, Heaven! grant Us one great Soul! One leading Mind would extricate the best Cause, from that Ruin which seems to await it, for the Want of it,” Adams wrote. “One active masterly Capacity would bring order out of this Confusion and save this Country.”

Puffers and Politics

Envy inevitably scarred Adams’ view of Washington. From Adams’ perspective, fawning courtiers — he called them “puffers” — had polished a flawed figure into one credited with characteristics “ascribed in Scripture only to God, and to Jesus Christ.”

The “history of our Revolution will be one continued lie,” Adams predicted. “The essence of the whole will be that Dr. Franklin’s electrical rod smote the earth and out sprung General Washington. That Franklin electrized him with his rod – and henceforth these two conducted all the policy, negotiations, legislatures and War.”

Adams profligately and unpleasantly gave vent to his jealousy and resentment of praises sung to Washington. Backhandedly denigrating the general’s lack of formal education even as he praised other attributes, Adams declared the other man insufficiently literate for the station he occupied: “You see I have made out the talents without saying a word about reading, thinking, or writing.”

He mused as to whether Washington would ever have achieved his position had he not wed the very wealthy widow Custis. He painted Washington as a “Successful Swindler of other Mens Laurells,” and claimed the other man benefitted greatly by working to move the capital to the banks of the Potomac, “raising the Value of his Property and that of his Family a thousand per Cent.”

Adams pooh-poohed celebrations of Washington’s birthday. Tellingly, when his firstborn and favorite son, John Quincy Adams, named his firstborn son George Washington Adams, the senior Adams expressed bitter disappointment.

Vitriol, which Adams did not reserve for Washington, played badly with the other man. Adams’ erudition, wit and fierce jealousy of whoever was in the spotlight when he was not grated on Washington, who forever felt the pain of his inadequate schooling and possessed a chronic fear of failure. Those elements combined to inspire a great hunger for loyalty from subordinates as well as an extreme sensitivity to criticism from individuals, including Adams, whom he regarded as right-minded.

Comrades to Cold Shoulder

Consequently, the pair’s initially close relationship was short-lived. Adams presided over the Board of War, in effect functioning as the rebel secretary of defense; he also was a pillar of the Continental Congress. Washington, contemplating a winter attack on Boston, clearly desired to cultivate Adams as an ally. He invited him to potluck dinners and war councils and introduced him as a prominent guest at ceremonial feasts with Indian chiefs. Reciprocity ensued. When in March 1776 Washington ran the British out of Boston, Adams proposed that Congress strike a gold medal, a touch Washington appreciated.

During that first year of the revolution, the two were closely aligned, as gauged by their epistolary exchanges. Washington writing to Adams in April 1776 employed the salutation “my dear sir” — a phrase the general reserved for intimates, otherwise using “Sir” or “Dear Sir” with those with whom he was on more familiar terms. This appears to have been the only time Washington referred to Adams in that fashion. Significantly, when he wrote to the other man after triumphing at Yorktown, Washington began his letter with a simple “Sir.” Clearly the tenor of their ties had changed, almost certainly owing to Washington’s perceptions regarding Adams’s ostensible hand in the Conway Cabal.

While Washington left no written commentary on what he believed may have been Adams’ role in the supposed coup attempt, evidence indicates that His Excellency came to view Adams with suspicion. Washington had a long memory for critics and knew of Adams’s choleric tendencies.

Washington’s concerns about Adams no doubt traced in part to his beloved Lafayette, who in February 1778 wrote to his friend and mentor, “I understood that John Adams Spoke very disrespectfully of your excellency in Boston.”

Adams’ service as vice president was shadowed by the Conway affair. In a confidential letter, James Madison, Washington’s most trusted advisor from 1787 to 1790, took a suspicious look at Adams prior to the election.

“J. Adams has made himself obnoxious to many particularly in the Southern states by his political principles,” Madison told the recipient. “Others recollecting his cabal during the war against General Washington, knowing his extravagant self-importance … conclude that he would not be a very cordial second to the general.”

Title Bout

To whatever degree the Conway matter drove the two men apart while they were leading the country, an incident known as the Titles Controversy exacerbated the situation. Washington, whose overarching goal was to strengthen the Union, always strove to steer around crises. No sooner had he and Adams taken office than one arose over how to address the new president, with Vice President John Adams at its center.

The Senate assigned the matter to a committee. Adams, quick to take up cudgels in causes he embraced, stridently maintained that without a fancy official title the nation’s leader would be considered a lightweight abroad. Foreigners, the veep claimed, would despise Washington “to all eternity” if he were simply labeled “President of the United States.” This would have devastating consequences, Adams claimed.

“It would not be extravagant prophecy that the want of titles may cost the country fifty thousand lives and twenty millions of money within twenty years,” he wrote, suggesting the official moniker be “His Majesty” or “His Benign Highness.”

The Senate committee recommended “His Highness the President of the United States of America and Protector of the Rights of the Same.” Critics joked that the Vice President should be called “His Rotundity.”

Adams’s proselytizing on nomenclature lit up critics of the new Constitution. To many, Adams’ yen for fancy titles seemed to validate Patrick Henry’s warning that the Constitution “squints toward monarchy.” By letter, Washington’s friend David Stuart warned the president to mind the tempest.

“Nothing could equal the ferment and disquietude, occasioned by the proposition respecting titles,” Stuart wrote, adding that the position Adams had staked out was making him “not only unpopular to an extreme, but highly odious.”

In reply, Washington lamented that Adams and his “high toned” protestations had “stirred a question which has given rise to so much animadversion; and which I confess, has given me much uneasiness,” especially if it made Americans think he endorsed Adams’s stance. Washington told Stuart he opposed adopting or using a high-falutin’ title lest adversaries of the new government use it as a weapon — which they did. Adams’ vigorous bleating in the Title Controversy soured Washington’s view of Adams as a politician and consensus builder, straining their professional relationship.

Though never estranged, the men did move in different orbits. Despite Adams’s express fealty, Washington only occasionally asked his opinion, and Adams exerted minimal influence. Now and again Washington did seek his vice president’s counsel and see him on social occasions formal and casual. Martha Washington and Abigail Adams became friends. The couples double-dated to the theater, and George and Martha, in a rare exception to his rule of accepting no invitations, went to Abigail’s and John’s rented Philadelphia estate, Bush Hill, for dinner. One suspects Martha orchestrated these gatherings.

Second Thoughts on No. 2

George Washington only reluctantly accepted the presidency. Persuaded to serve a second term, he never explicitly told Adams he wished to keep him as vice president. Only when Washington decided against seeking a third term did he spend more time with his No. 2 and likely successor, inviting Adams to the theater on March 9, 1796, while Abigail was home in Braintree.

This shift surprised Adams. Later that month, he wrote Abigail that at the end of a large state dinner, he had found himself alone with the president in close conversation.

“He detained me there till Nine o Clock and was never more frank and open upon Politicks,” John told Abigail. “I find his Opinions and sentiments are more exactly like mine than I ever knew before, respecting England and France and our American Parties.”

Adams’ startlement shows the habitual distance that had grown between the men. Washington clearly preferred that Adams and not Jefferson succeed him, but Adams later told Abigail he knew that fact with certainty only because Martha Washington so informed him.

Washington and Adams’ Final Faceoff

The final interaction between the two presidents was their most highly charged. After defeating Thomas Jefferson for the office by three votes in 1796, President John Adams faced the daunting prospect of war with France over the Jay Treaty, which seemed to ally America with Great Britain. The dispute had begun while Washington was still in office. By the time of Adams’s inauguration, France had seized over 300 American ships.

The crisis made it unlikely that Washington, a staunch critic of French actions, would remain placidly retired under his own “vine and fig tree.” Who better to command the new army and save the country from France than the man who had saved the country from Great Britain?

Washington’s willingness, if not eagerness, to serve may be seen in his decision at mid-June 1798 to write President Adams a “Dear Sir” letter, his first communique to Adams since retiring. The former president praised his successor’s tough stance toward France and in a telling gesture cordially invited Adams to visit and stay at Mount Vernon.

“We must have your name, if you, in any case, will permit us to use it,” a pleased Adams replied, requesting that Washington return to head the military. “There will be more efficacy in it, than in many an army.”

Confident Washington would lead the army, the president acted before receiving Washington’s agreement to accept a commission.

Hamilton’s Shot

Trouble soon arrived. Adams had only a loose grasp of Washington’s conditions for taking command. The sticking point was simple. Washington desired Alexander Hamilton to be his second in command. Adams did not. He despised Hamilton — labeling him “that bastard brat of a Scottish peddler” — and wanted Hamilton nowhere near to being de facto commander of the American army.

By conditioning his acceptance on that point and insisting on naming his general officers, Gen. Washington was undermining the commander in chief, something President Washington would not have tolerated. Washington had Adams over a barrel. If he could make Washington president, he would do so, Adams declared, “but I never said I would hold the office & be responsible for its exercise, while he should execute it.”

Adams reluctantly assented to Hamilton’s appointment, later explaining to Rush, “I was no more at Liberty than a Man in a Prison, chained to the floor and bound hand and foot.”

Daring diplomacy on Adams’ part extinguished the quasi-war, but not in time to influence the 1800 election in his favor. Fearing a Jefferson presidency, many Federalists had wanted Washington to run again. Adams believed Washington would have run and would have won, but his sudden death in December 1799 removed that possibility. Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson defeated Federalist Adams for the presidency.

Post-Mortem

Adams’ reference to his predecessor as his “lost brother” is intriguing. Brothers may battle together in common cause but also descend into intense rivalry. In the Bible, the first brothers are Cain and Abel, sons of Adam and Eve. Each made a sacrifice to the Lord, who accepted Abel’s offering but rejected Cain’s, leading to his murderous rage and the death of Abel.

While Adams clearly never wished Washington harm, it is instructive to think of George Washington as Abel, the favorite son, and John Adams as Cain, the envious son. These American “brothers” performed heroic sacrifices on the altar of fame in hopes of winning glory across the ages. Washington’s sacrifices earned him immortality as the father of his country, “first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.” Adams, for all his sacrificial revolutionary efforts, acknowledged that “Mausoleums, Statues, Monuments will never be erected to me.”

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.