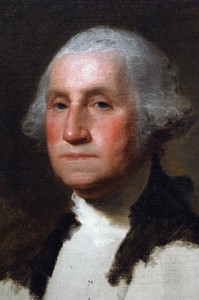

Along with the look of leadership, Washington possessed a leader’s physique and personality. He was profoundly ambitious, eager not only for honor but for history’s most elusive prize, fame that persisted through the ages, which he achieved by passing through the temple of virtue. (Jon Helgason/dreamstime.com)

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]s a student of George Washington for over 25 years, I find one of American history’s more puzzling aspects to be the existence of serious debate about who among American statesmen deserves the premier position. Although I do not think the matter debatable, I would argue for George Washington, who was truly our “Indispensable Man,” essential not only in winning America’s independence, but also in the successful drafting and ratification of our Constitution and Bill of Rights. He was the indispensable man keeping the country united and at peace during its vulnerable early years, guiding a disparate group of states toward nationhood. We forget how close the American experiment came to extinction and how critical Washington was to preventing that endeavor’s collapse. He was the Atlas of our Revolution, the man who made America possible. Without Washington, there would have been no Union for Abraham Lincoln to save, or for today’s Americans to joust and squabble over. His record is without parallel in our history.

How did Washington become such a remarkable leader?

Certainly not by chance, though great good fortune did figure in his personal evolution. Time and again, almost uncannily, he was the right man in the right place at the right time, not only in matters of statecraft but also on the battlefield, where he survived a significant number of close calls, unscathed as bullets whizzed around him.

George Washington succeeded as a leader because he looked the part, he had the necessary personality and requisite character, and he was an unblinking realist, rich with talents.

Washington was a superb physical specimen. Roughly 6’2”—today’s 6’5”—he was powerfully built, a figure of prodigious strength, yet with a graceful carriage and majestic walk. A superb athlete, he was widely acknowledged as Virginia’s best horseman.

Countless contemporaries testified to his charisma. Washington, James Monroe said, possessed “a deportment so firm, so dignified, but yet so modest and composed I have never seen in any other person.” Another acquaintance recollected, “There was in his whole appearance an unusual dignity and gracefulness, which at once secured him profound respect, and cordial esteem. He seemed born to command his fellow men.”

“No man could approach him but with respect,” Gouverneur Morris wrote. “None was great in his presence.” Henry Knox noted that an aide to British General William Howe appeared “awestruck” upon being presented to General Washington. Another man, who had been presented to the Kings of England and France, said neither monarch induced the feeling he experienced meeting Washington. French officer upon French officer spoke similarly after interchanges with the man they and many others called His Excellency. Benjamin Rush declared one “could distinguish him to be a general from among 10,000 people,” adding that there was not a European ruler who, alongside Washington, would not look like a servant.

Along with the look of leadership, Washington possessed a leader’s personality. He was profoundly ambitious, eager not only for honor but for history’s most elusive prize, fame across the ages. In Paul Longmore’s telling words, “Throughout his life, the ambition for distinction spun inside George Washington like a dynamo, generating the astounding energy with which he produced his greatest historical achievement—himself.” Washington hungered for secular immortality.

In adversity and in disappointment, he persevered, developing the ability to prevail amid a host of troubles.

Early in the French and Indian War, he risked arrest and having his brains blown out as he attempted to gather supplies crucial for the coming campaign.

Through the Revolution, he amassed a record of defeats and near-defeats that he salvaged by deft responses. The Revolution’s financier, Robert Morris, said Washington “feeds and thrives on misfortune by finding resources to get the better of them,” whereas lesser leaders “sink under their weight, thinking it impossible to succeed.” Morris saw in Washington a “firmness of mind” and a “patience in suffering” that gave him an “infinite advantage over other men.”

Washington’s ambition and determination had their match in his passions. We forget that he was a man of profound intensity.

“Those who have seen him strongly moved will bear witness that his wrath was terrible,” Gouverneur Morris wrote. “They have seen boiling in his bosom, passion almost too mighty for man.”

Those passions were clear to artist Gilbert Stuart. Studying Washington, Stuart said, he discovered a face “totally different from what I had observed in any other human being. The sockets of the eyes, for instance, were larger than what I had ever met before, and the upper part of the nose broader…All his features were indicative of the strongest passions…Had he been born in the forests…he would have been the fiercest man among the savage tribes.” He exuded the dignity of a tribal sachem and possessed the courage of a ferocious warrior. His heart-stopping bravery leading the Continental Army worried, even unnerved, his aides but inspired his men as well as onlookers. In Jefferson’s words, Washington “seemed incapable of fear.”

He practiced what today’s statesmen call Realpolitik. In Joe Ellis’s phrase, Washington was a “rock-ribbed realist.” Viewing humanity darkly, Washington operated from a visceral understanding of the world’s caprice.

“What, gracious God, is man!” he wrote.“That there should be such inconsistency and perfidiousness in his conduct?”

Washington knew how to get things done. His modesty and self-deprecation masked and still mask his skill as a politician and effectiveness as an executive. (Stanley Massey Arthurs/Virginia Historical Society/Bridgeman Images)

Repeatedly, he argued that since men as well as nations are driven by their interests—“The motives which predominate most in human affairs [are] self-love and self-interest,” he wrote—any form of government failing to account truly for human nature would itself fail. “We must take the passions of men as nature has given them,” he wrote. “A small knowledge of human nature will convince us that, with far the greatest part of mankind, interest is the governing principle and that almost every man is more or less under its influence.”

While not discounting the power of patriotism, Washington argued, “a great and lasting war can never be supported on this principle alone. It must be aided by a prospect of interest or some reward.” He believed utterly in and often acted upon the imperative to marry ideals to interest with open eyes. “We must make the best of mankind as they are, since we cannot have them as we wish them to be.”

Washington was able to “make the best of mankind as they are” because, as Richard Norton Smith observed, he was “awash in talents.” Foremost among his gifts were a keen intelligence, a phenomenal memory, remarkably astute judgment, and deep understanding of power and how to exercise it. Almost every Washington biographer recognizes his good heart, but most give short shrift to his good head, and it was the combination of those two that made possible Washington’s success as a general and later as a president. He was a master executive who knew how to get things done. Jefferson described his compatriot’s talents in this realm as “superior, I believe, of any man in the world.”

In The Genius of George Washington, a little 1980 book worth reading, Edmund Morgan argues that Washington’s genius lay in his dual understanding of military and political power. Washington’s modesty and self-deprecation masked and still mask his skill as a politician and effectiveness as an executive. He was a better politician than a general, in many ways a political genius, as well as a keen judge of character and ability.

Washington had few peers in his capacity to identify talent and in his willingness to engage “minds far abler than mine.” He was comfortable enough in his own skin to enlist young geniuses and to inspire them to

great deeds.

An elitist by temperament and upbringing, Washington believed that “to support a proper command” a leader had to maintain a certain separation, and he did so as a matter of course. However, his bearing combined with that reserve to form a persona that, leavened by native amiability, was extremely appealing. Abigail Adams described Washington as having “a dignity that forbids familiarity, mixed with an easy affability that creates love and reverence.”

Few men had a finer sense of what constitutes proper public conduct. Sharply self-critical, he knew his strengths and his weaknesses and strove constantly to enhance the former and correct or minimize the latter. Washington was not one to write reflectively, but that does not mean he led an unexamined life.

Though he lacked great oratorical skill, he was capable of eloquence in act, if not always in language. A lifelong theatergoer, Washington had a magnificent sense of stagecraft and gesture that he consciously employed in such instances as when, appearing in 1775 at the Continental Congress, then on the verge of declaring war, he took care to wear his brand-new military uniform; when, after the battles at Trenton and Princeton, he urged soldiers to reenlist; when he rallied his men at the Battle of Monmouth; when, in a stunning moment at Newburgh, he unmanned mutinous officers with only reading glasses as a prop; when moving his officer corps to tears in their farewell encounter at Fraunces Tavern; when he emotionally returned his commission to Congress at Annapolis after successfully concluding the war; and when he insisted, following John Adams’s inauguration, that Jefferson precede him out of the hall, to emphasize that a former president was an ordinary citizen.

George and Martha Washington with her children, John and Martha Custis. The portrait was made after the children had died. (Edward Savage/National Gallery of Art/Bridgeman Images)

These highly charged moments were not accidental. “Through the years not only did Washington perform at an amazing level in public and on the field, but he also meticulously studied his own performance and the public’s view of it,” author Phil Smucker observed. “If he was a consummate actor, he was also an accomplished director of the man in the mirror.”

Washington did not pose for posing’s sake but used his skill at the “politics of self-presentation” to unify support for American independence and republican government. A leading Washington scholar argued for calling him “The Unifier,” a phrase succinctly capturing what Washington sought. A collaborator, he often put aside personal grievances to promote and achieve larger goals. “I have undergone more than most men are aware of, to harmonize so many discordant parts.” He eloquently urged others to do likewise. “How strange it is that Men, engaged in the same Important Service, should be eternally bickering, instead of giving mutual aid! Officers cannot act upon proper principles, who suffer trifles to interpose to create distrust and jealousy.” Or again, “How unfortunate, and how much is it to be regretted then, that whilst we are encompassed on all sides with avowed enemies and insidious friends, that internal dissensions should be harrowing and tearing at our vitals. [Unless corrected] in my opinion the fairest prospect of happiness and prosperity that ever was presented to man will be lost—perhaps forever!”

Washington’s words of praise for a French admiral reflect his own mindset: “A great mind knows how to make personal sacrifices to secure an important general good.”

General Washington showed brilliant talent as a diplomat in resolving difficulties—and there were many—arising early in America’s alliance with France, such as the failure of the French fleet during the 1778 Newport expedition. The fleet’s sudden withdrawal, which left the Americans vulnerable and furious, triggered virulent Francophobia.

Above all, Washington wanted to prevent resentment of France from undermining the new accord, which he saw as crucial to the rebel cause. So he cautioned his generals to be prudent and to avoid “injurious consequences,” even if prudence meant a white lie as to why the French left Newport. “It is our duty to make the best of our misfortunes and not to suffer [allow] passion to interfere with our interest and the public good,” he wrote in a letter to General William Heath.

Ultimately, character is the decisive factor in assessing an individual. The ancient Greeks distilled that nebulous term into four virtues, all of which Washington had in abundance: Fortitude, the strength of mind melded to physical and moral courage that enables its possessor to persevere in adversity; temperance, the self-control to govern passions and appetites; prudence, practical wisdom and the ability to make the right choice in the moment; and justice, the capacity for fairness, honesty, lawfulness, and promise keeping.

In 1786, Washington assured a friend, “I do not recollect that in the course of my life I ever forfeited my word, or broke a promise made to anyone.” To conduct oneself, especially in times of crisis, with integrity, is the fundamental litmus test of character. “It is difficulties that show what men are,” the Stoic Epictetus wrote. “No man is free who is not master of himself.” In his time, Washington learned and lived these truths.

Washington was not only a great man; he was also a good man. He sought not mere notoriety but “honest fame.”

Asked how to achieve that, Socrates replied, “Study to be what you wish to seem.” Washington pursued those studies with remarkable results. He became the man he strove to be—the embodiment of revolutionary virtue. How closely his behavior comported with his ideals!

He desperately wanted to enter the temple of fame but only if he could do so by way of the temple of virtue.

George Washington combined extraordinary charisma and leadership skills so as, in Abigail Adams’s words, to have the potential to be “a very dangerous” man. And yet, because Washington was, in her words, “one of the best intentioned men in the world,” he used his remarkable talents to lead in the “glorious cause” of expanding liberty and republican values—not only for his generation of but also for millions yet unborn.

The gift and opportunity George Washington gave his beloved country were priceless. Only time would show how the country he fathered would use it.✯

This story was originally published in the November/December 2016 issue of American History magazine. Subscribe here.