The full moon cast long shadows across the 3,000 dead and wounded sprawled in grotesque piles throughout the meadow. Moans disturbed the night’s stillness as the dying lingered for moments before falling into death’s painless darkness. Through the moonlight came a solitary figure, a lame, drunken old soldier stumbling over the corpses, come to inspect his work. He stopped where the center of the battle line had been and drank deeply from a wine jug. A smile crossed his lips. Then Philip II of Macedon, Greece’s greatest general, began to dance upon the bodies littering the battlefield at Chaeronea.

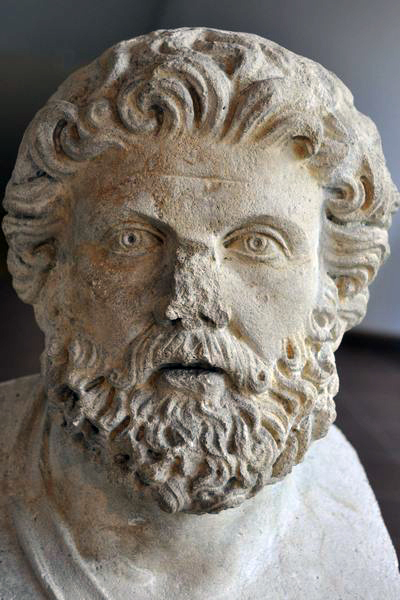

Philip II was many things—father of Alexander the Great; unifier of Greece; founder of the first territorial state in Europe with a centralized administration; author of that nation’s first federal constitution; the West’s first national king; creator of the first Western national army; the first great general of the Greek imperial age; strategic and tactical genius; military reformer; and dreamer of bold dreams. Philip’s military and political brilliance shaped both his own age and the future of Western military history. Had there been no Philip to assemble the resources and create the strategic vision to bring into being the first modern, tactically sophisticated army in Western military history, Alexander’s achievements would not have been possible.

Born in 382 BC, Philip was the youngest of three sons of Macedonian king Amyntas II. At 15 he was sent as a hostage to Thebes to help ameliorate the dynastic crisis then engulfing the Macedonian royal house. While in Thebes, Philip lived with Pammenes, a skilled general and friend of the great Epaminondas, the best military tactician in all Greece. Philip was an eager student of war and was particularly impressed with Pelopidas, the great Theban general and commander of the Sacred Band, an elite force of some 300 handpicked hoplites. It was while watching the Theban army train that Philip learned the importance of infantry maneuver and using cavalry in concert with infantry. When Philip’s brother, Perdiccas III, regained the Macedonian throne and recalled Philip from Thebes, Philip was made a provincial governor and given a free hand to raise and train troops. For the next five years he experimented with new infantry formations and tactical doctrines.

In 359 BC Perdiccas marched against the Illyrians in another of the interminable border wars that plagued Macedonian kings for centuries. He left Philip behind to govern as regent. Perdiccas was killed in a defeat that also cost the lives of 4,000 Macedonian soldiers. So, at the age of 23, Philip became king of Macedonia and immediately moved against the five wouldbe usurpers who challenged him for the throne. Within a year three of them were dead, the others driven into exile later to be captured and killed. Macedonian politics was not for the weak or squeamish.

Philip quickly had to deal with powerful enemies. The Illyrians and Paeonians were preparing to reinvade Macedonia. The young king gathered up every available man, first attacking and defeating the Paeonians. Then, with 10,000 infantry and 600 cavalry, he turned on the Illyrians, crushing them in a pitched battle near Monastir and killing 7,000 of the enemy during a ruthless cavalry pursuit. Within a year, Philip had neutralized the enemies on Macedonia’s northern and western frontiers. He then turned to the task of rebuilding the army into an instrument with which to forge an empire.

Over the course of his campaigns, Philip designed and tested a new army radically different in structure, tactics and operational capabilities from those elsewhere in Greece. And behind the redesign of the new army lay a clear strategic vision: Philip intended to conquer all of Greece and unite it under Macedonian suzerainty. With that accomplished, he intended to use the manpower and resources of a united Greece to attack Persia. To manage this, he needed a military machine that could succeed against both Greek and Persian methods of war. To defeat the Greeks, Philip had to find a way to deal with the heavy hoplite infantry phalanx. Defeating the Persians, however, was a more complex problem and required the development of several military capabilities, all of which were new to the Macedonian army.

First, if his army was to deploy over great distances for long periods, Philip needed an effective logistics system. Second, an army operating far from its home base required more rapid means of reducing cities than the usual Greek method of blockade and starvation. Third, because Persian cavalry was so strong, Philip’s heavy infantry had to be able to blunt the cavalry’s shock power. Fourth, mobility on the battlefield needed improvement, and his cavalry had to develop tactics to counter the excellent Persian light infantry. And fifth, new tactical doctrines were required if these combat arms were to be utilized in concert. Philip found solutions to all these problems.

His first move was to require one in every 10 able-bodied men to serve in the army under a system of regular pay and training, which transformed the Macedonian military from a hodgepodge militia into a standing regular army. He reconstituted the Macedonian infantry into a stronger phalanx of 4,096 men, comprising four regiments of 1,024 men each. Each regiment had four 256- man battalions. Unlike earlier Greek infantry formations, the new Macedonian phalanx was a self-contained fighting unit augmented by its own light infantry and cavalry units. Once deployed, these units were completely self-sustaining and could maneuver independently, permitting much greater flexibility than had previously been possible. By the time of Philip’s death, the Macedonian field army comprised 24,000 infantry and 3,400 cavalry.

In addition to restructuring his army, Philip invented a completely new tactical infantry formation. The original Macedonian phalanx deployed in 10 files, each 10 men deep, a simple square that made it possible to train troops quickly in simple tactical formations and maneuvers. As the infantry gained experience, the phalanx deployed 16 men deep—twice the depth of the Greek hoplite phalanx—and was capable of a number of sophisticated battle drills and tactical formations, including the hollow wedge to drive through Greek hoplite infantry lines. The Macedonian infantryman carried a new weapon, the sarissa, a 13- to 21-foot-long pike made of cornel wood with a blade at one end and a butt plate on the other to lend it balance. The sarissa weighed about 12 pounds and provided much greater reach than the traditional doru, a 7-foot hoplite infantry spear, permitting the phalanx to hold hoplite formations at bay and affording Macedonian infantry the advantage of always landing the first blow. The sarissa could be disassembled and carried with a strap across the soldier’s back.

Macedonian infantrymen wore the standard Greek hoplite helmet and leg greaves, but no body armor. Each carried an aspis, a 3-foot diameter, round, bronze-covered wood shield, secured to the body by a shoulder strap. This freed both hands to wield the sarissa, thus enabling Macedonian infantrymen to easily pierce the armor and shields of Greek hoplites. Philip called his infantry the pezhetairoi (“foot companions”), endowing it with prestige traditionally reserved for the Companions, cavalry warriors of the Macedonian king.

Philip’s new infantry formations were based on radically new concepts of tactical employment. Unlike in traditional Greek armies, the Macedonian infantry was not intended to be the primary killing arm. Its purpose was to anchor the line and act as a platform for the maneuver and striking power of the heavy cavalry. By holding the hoplite phalanx at bay with its mass and longer spears, the Macedonian phalanx immobilized the hoplite formation until cavalry could strike it in the flank or rear. But the new phalanx could also be used offensively. When formed as either a solid or hollow wedge, the weight and force of the phalanx could easily drive through a hoplite infantry line, opening a gap through which the cavalry could strike the enemy rear.

The Macedonian phalanx did not usually deploy at the leading edge of the line, but was held back obliquely. The cavalry deployed in strength on the flank, connected to the infantry center by a “hinge” of heavy elite infantry called hypaspists, armed either in traditional hoplite fashion or with the sarissa, depending upon circumstances. The new concept was to engage the enemy not at the front, but from the flank or at an oblique angle, forcing him to turn toward the attack. As the cavalry pressed the flank, the slower infantry, held back obliquely, advanced toward the enemy center in hedgehog fashion—sharp spears bristling outward. If the enemy flank broke, the cavalry could either envelop or press the attack as the infantry closed, using the phalanx as an anvil against which to hammer the hoplites. If the enemy flank held, it still had to deal with the impact of the massive phalanx falling upon its front. Philip’s innovative new formations, and their new methods of tactical employment, produced the most powerful and tactically sophisticated infantry force ever known to Greece.

The cavalry was the Macedonian army’s decisive arm. Philip’s cavalrymen were each equipped with a sword and a 9-foot javelin, the xyston, used to spike opponents through the face in close combat. Macedonian cavalry were also adept at employing the sarissa. Organized into squadrons of 120, 200 or 300 horse depending upon the mission, Macedonian cavalry attacked with xyston or sarissa held overhand and resting on the shoulder to execute a downward thrust. Once the victim was impaled, a horseman would abandon his spear and fight on with sword. Philip’s cavalry typically attacked in wedge formation, the narrow end forward, a tactic he copied from the Thracians and Scythians. The ratio of cavalry to infantry in Philip’s new army was one to six, twice that of the Persians and the largest cavalry-to-infantry force ratio of any army in antiquity. Philip’s cavalry was particularly deadly in the pursuit, where the sarissa’s long reach gave the Macedonians a significant advantage in riding down and skewering fleeing enemy cavalry and infantry.

Macedonia boasted a long tradition of cavalry warfare, and Philip’s cavalry was the best. Macedonian horses were larger and stronger, descended from Persian and Scythian stock bred on the plains of Media and the Danube. If we are to believe Arrian, the Roman cavalry officer and sole contemporary source with military experience, it seems likely that when attacking in wedge formation and employing the longer reach of the sarissa against infantry, Macedonian cavalry could do what no other cavalry of the day could—break through an infantry line. Diodorus says that is exactly what Alexander’s cavalry did at the Battle of Chaeronea.

Within four years of taking the throne, Philip had forged an army superior to any in Greece. As remarkable as this was, however, the new army was insufficient for creating the empire Philip had in mind. His army still lacked the logistical capability to sustain itself in the field over long distances and initially had no siege ability with which to force a strategic decision by rapidly subduing cities. Philip’s solutions to these problems set the example for all future Western armies. He prohibited the traditional Greek practice of allowing each soldier to bring an attendant on military campaigns, allowing just one attendant for every 10 infantrymen and one for every four cavalrymen. This transformed the attendants into a logistics corps that served the whole army. He also forbade soldiers from bringing wives and other women, reducing the size of the noncombatant contingent. Philip outlawed the use of drawn carts except for those few designated as ambulances and transport for siege machinery. Horses and mules replaced oxen as pack animals. The effect on speed and mobility was remarkable, increasing the army’s rate of movement to 13 miles a day, with cavalry units covering 40 miles from sunrise to sunset. Absent carts, the Macedonian soldier became a beast of burden, carrying 10 days’ rations, 30 pounds of grain and another 40 pounds of equipment and weapons. This enabled Philip to reduce the number of pack animals in his army by 6,000, creating the fastest, lightest, most mobile army the West had ever seen. Taken together, these logistical reforms made it possible for the first time in Greek history for an army to achieve strategic surprise, allowing Philip to choose the battlefields on which he fought.

But even a mobile army risked ruin in enemy territory if it could not quickly subdue walled garrisons and cities. Philip was the first Greek general to create a department of military engineering in his army and make siege operations an integral part of his tactical repertoire. It was likely Macedonian engineers who developed the prototype of the torsion catapult. Philip could now control the tempo and direction of warfare on a strategic and tactical level. These innovations spelled the end of the city-state as the dominant actor on the Greek military stage. The future belonged to the national territorial state Philip had created in Macedonia.

By 356 BC Philip was in a position to begin his wars of conquest against the Greek city-states. For the next 20 years he engaged in war, diplomacy, intrigue, treachery, bribery and assassination. He conducted 29 military operations and 11 sieges and captured 44 cities during this career, in the process losing an eye and sustaining injuries that left him lame. By 339 BC it was clear that despite his infirmities, Philip intended to master all of Greece. In September of that year he occupied Elateia, a key junction on the main road running through Thebes to Athens. Thebes, though a traditional enemy of Athens and technically Philip’s ally, recognized that the only way to avoid incorporation into his Macedonian empire was to form a military alliance with Athens. The Athenian army marched into Boeotia, linked up with the Theban army and took up positions in the northwest passes. Their disposition effectively blocked both of Philip’s routes of advance—the first along the road from Elateia to Athens, the second across the Corinthian Gulf at Naupactus, its narrowest point. For almost nine months Philip’s route south was blocked. Then then came the decisive Battle of Chaeronea.

Following his victory over the Greeks, in October 338 BC Philip summoned the Greek city-states to a peace conference at Corinth, presiding over what arguably would be his greatest achievement—legalizing Macedonia’s hegemony over Greece. He proposed the League of Corinth, a defensive alliance in perpetuity among the Greek city-states and Macedonia. Philip was to be appointed hegemon of the league’s joint military forces, whose mission was to ensure the security of Greece. Philip was also to be the strategos autokrator, or supreme commander in chief, of all Macedonian and league forces in the field. One by one the citystates ratified the agreement. Thus Philip united Greece in a single federation for the first time in its history.

In the summer of 337 BC, Philip placed before the league’s council his plan for war on Persia. The proposal was carried, and in the spring of 336 BC Philip sent 10,000 men across the Hellespont to establish a beachhead in Ionia and provoke secession of the Asiatic Greek states from Persian control. Philip was to follow with the main body in the fall, but before he could embark, he was assassinated by Pausanias, one of his own bodyguards.

Philip was the strongest of the few strong men who had appeared on the stage of Greek history since the end of the Peloponnesian War, and his death marked the passing of the classical age of Greek history and warfare and the beginning of the imperial age. Although the latter is marked by the victories of Alexander and rule of the three empires that followed his early death, the debt owed Philip is very great indeed. It was Philip, after all, who dared to dream of a united Greece despite four centuries of failed efforts by Athens, Thebes and Sparta. To Philip belongs the title of first great general in the new age of Western warfare, an age he fathered by introducing a new instrument of war and the tactical doctrines to make it succeed. As a statesman, he had no equal in his time—even Alexander’s achievements did not outlive his death. Philip’s accomplishments survived long enough to provide Alexander the strategic foundation and means for his war of Persian conquest. As a practitioner of the political art, Philip had no equal—even Nicollò Machiavelli might have smiled at Philip’s ability to gain his ends by diplomacy as well as by force. There were few minds more facile than Philip’s in the art of realpolitik. In all these things, he was greater than Alexander. The son became a romantic hero, but the father was the great national king.

For further reading, Richard A. Gabriel recommends: Philip of Macedon, by N.G.L. Hammond, and the author’s own Greater Than Alexander: Philip of Macedon, Greece’s Greatest General.

Originally published in the March 2009 issue of Military History. To subscribe, click here.