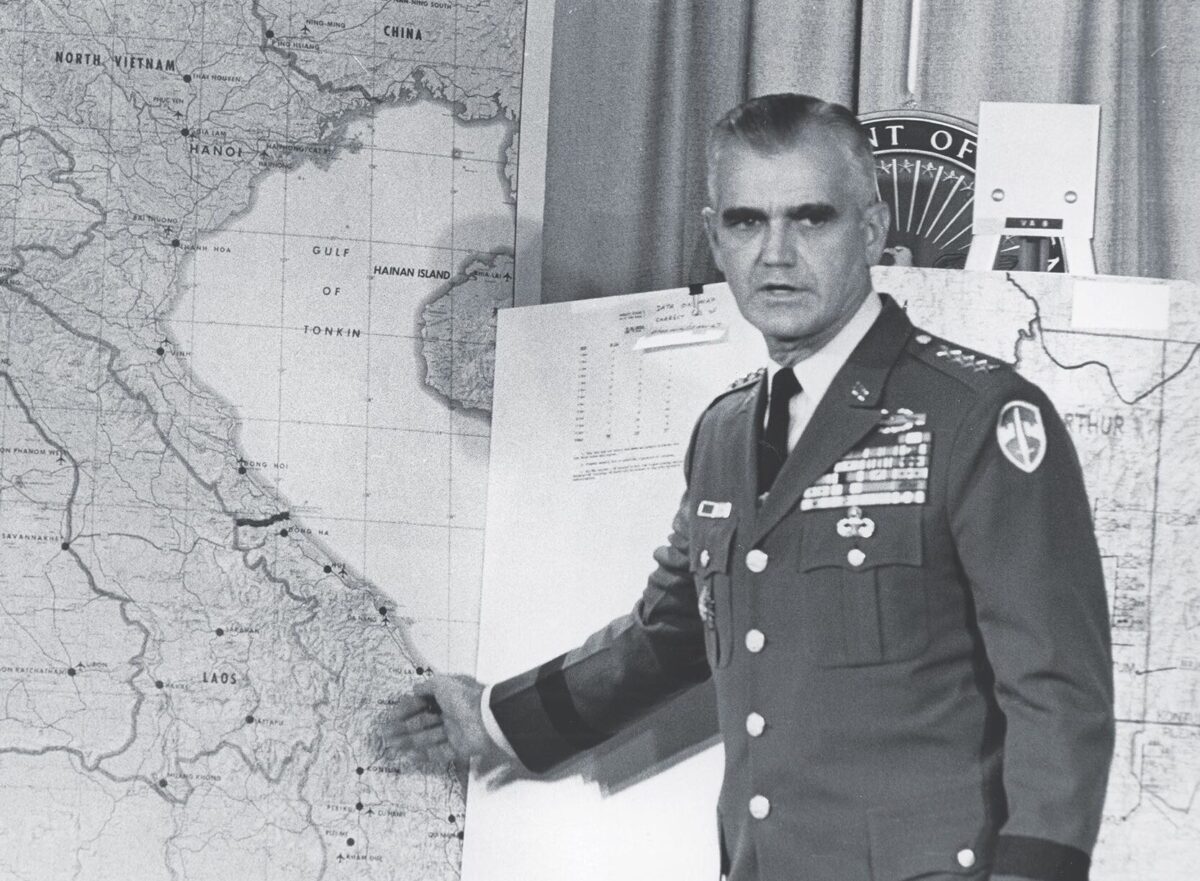

Attrition was an important part of Gen. William Westmoreland’s approach, but never to the exclusion of other methods. Some have portrayed the 1964-68 leader of Military Assistance Command, Vietnam as an unimaginative officer who failed to grasp the complexities of the war. They say Westmoreland fixated on enemy body counts and failed to pursue alternative strategies that would have produced better results. Having researched and written about the Vietnam War for more than 20 years, I am convinced that Westmoreland pursued the most logical and sophisticated strategy that he or any other U.S. commander could follow given the inherent limitations on his authority.

In military affairs, attrition is one of several basic approaches nations or leaders can employ to defeat their enemy. In its most basic form, attrition is the process employed to degrade the enemy’s fighting strength, usually by killing troops or destroying military equipment. Commanders can also maneuver their forces to take key terrain, thereby cutting enemy supply lines, capturing important logistical or political centers, and gaining control over people and natural resources.

A third approach is to use persuasion—such as psychological warfare and propaganda—to lessen the enemy’s resolve, encourage the surrender of opposing troops, and build popular support for one’s own side. Last, combatants can form alliances to secure additional military resources from friendly nations, exert diplomatic pressure on the enemy and obtain new intelligence sources.

During the war, Westmoreland employed all four methods—attrition, maneuver, persuasion and alliances—in varying proportions, based on the resources available and the changing military situation in South Vietnam during his time as MACV commander. Attrition played the dominant role in Westmoreland’s strategy out of necessity.

Before the South Vietnamese government could root out Viet Cong insurgents at the hamlet level, a process known as pacification, Westmoreland had to contain and degrade the communist main force units of full-time fighters that would have overwhelmed the South Vietnamese army. At the same time, the MACV commander maneuvered to disrupt communist supply lines and protect key assets like roads and cities. Had he been given permission, Westmoreland would have cut the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos and invaded communist sanctuaries in Cambodia.

In the propaganda realm, he supported a robust psychological warfare program to induce enemy defections and supported pacification programs to win the “hearts and minds” of villagers. Westmoreland was also a skilled diplomat and alliance builder who maintained excellent relations with the South Vietnamese and the other nations fighting alongside the Americans. He committed significant resources to training, upgrading and expanding the South Vietnamese armed forces as quickly as the Saigon government could handle the growth and as soon as equipment became available.

Given the hand he was dealt, Westmoreland pursued the most appropriate strategy any MACV commander could devise between 1964 and 1968.

This article appeared in the April 2022 issue of Vietnam magazine.