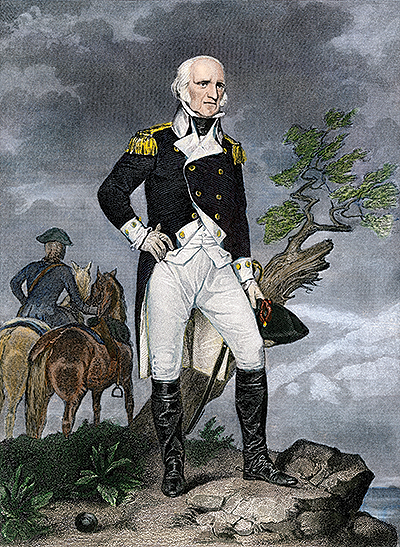

Benedict Arnold and John Stark were among the greatest fighting men of the American Revolution, yet both were passed over by Congress for promotion when less worthy warriors received the ranks they sought. The rancor of the insult turned Benedict Arnold from the hero of Saratoga into the traitor who tried to sell West Point to the British. John Stark may have remained angry, but he never strayed from the Patriot cause. Indeed, he may have saved the members of the Second Continental Congress from traitors’ deaths on the gallows had Britain won the war.

Stark, the second-born son of Scotch-Irish immigrants in New Hampshire, seems to have come into the world with a warrior spirit and a deep sense of clan loyalty. Hunting and trapping along the Baker River in the White Mountains in late April 1752 as a young man of 23, he was captured along with friend Amos Eastman by an Abenaki war party. Stark was able to warn older brother William, who escaped, but their friend David Stinson was killed. (Would-be rescuers later found his body stripped and scalped.)

When the Abenakis got Stark and Eastman back to their village in Quebec, they forced the two “Yengeese” to run the gauntlet between two lines of club-wielding warriors, each while holding a ceremonial pole adorned with the skin and feathers of a loon. Eastman held his pole aloft and endured the beating, falling exhausted at the far end. Stark followed. But as he made his way down the line, he kept his attackers largely at bay with wide sweeps of the pole. The bemused elders were so impressed they welcomed both young men into the tribe. Adopted into Abenaki families, they were taught the language and the Indian mode of warfare. Within weeks officials from the Province of Massachusetts Bay ransomed Stark and Eastman—for 103 Spanish dollars and 60 Spanish dollars, respectively—but John and his Abenaki family exchanged visits for years after the border fighting ended.

Stark’s toughness and knowledge of Indians landed him stints as a British military scout, followed by commission as a second lieutenant in Rogers’ Rangers, the famed reconnaissance and special operations unit raised in New Hampshire by Capt. Robert Rogers at the 1754 outset of the French and Indian War. Stark fought well and was promoted to captain. (Between engagements he even found time to marry local girl Elizabeth “Molly” Page.) But when told in 1759 the Rangers were to raid the Abenaki village at St. Francis, Quebec—the very home of his Indian foster family—he refused to join the expedition. Stark may have been prescient: The vaunted Rangers killed 30 Indians (two-thirds of whom were women and children, according to Indian sources), and on the return march Rogers lost nearly 50 men killed or captured by vengeful Abenakis. At the end of the campaign Stark returned to the quiet life of a New England farmer and sawmill operator.

When the American Revolutionary War broke out in earnest around Boston in 1775, Stark, according to his memoir, “mounted a horse and proceeded toward the theater of action.” Appointed colonel of a militia regiment by fellow New Hampshiremen, Stark led the unit to Bunker Hill, where he helped defend the left flank of the Patriot line. His men repulsed three charges by the Royal Welch Fusiliers, handing huge losses to the Redcoats, who never took Stark’s sector. The New Hampshiremen then covered their fellow Americans’ retreat. In the wake of that action Gen. George Washington informally attached Stark’s volunteers to the Continental Army. Returning stateside from an abortive invasion of Quebec, Stark fought in New Jersey at Trenton in 1776—the battle that saved Washington’s army—and at Princeton in the new year.

Stark resigned his commission, effective March 22, 1777, though he stood ready to defend his native New Hampshire. His chance came later that year

At the end of that campaign Stark again returned to New Hampshire, this time to recruit more men to the Patriot cause. In his absence Congress appointed Enoch Poor a brigadier general of Continentals. Stark had a low opinion of Poor, as the former New Hampshire assemblyman and junior colonel had refused to march to the support of the Massachusetts men at Bunker Hill. Taking Poor’s promotion over his own head as a studied insult, Stark resigned his commission, effective March 22, 1777, though he stood ready to defend his native New Hampshire. His chance came later that year.

The British had devised a strategic plan to divide the rebellious New England colonies from the less antagonistic Middle Colonies, like heavily Dutch New Jersey and German pacifist Pennsylvania, by marching down from Canada and up from New York City to close the Hudson River to commerce and communication. The principal British and German mercenary army was that of Maj. Gen. John Burgoyne, a playwright and bon vivant who brought along his portable wine cellar and elegant mistress on campaign. Burgoyne’s Germans—mostly Brunswickers—were led by Maj. Gen. Friedrich Adolf Riedesel, who thought his commander a poor disciplinarian. Yet Burgoyne managed to recapture Fort Ticonderoga on July 6 without a fight, earning a promotion to lieutenant general. In the aftermath he instructed the Germans to drive off the abandoned cattle of “those acting in the service of the Rebels,” though he was merciful enough to spare the Patriot families their milk cows. But allied Indians under Riedesel’s nominal command cut the throats of the cattle to loot their bells. Few cattle reached the British camp.

The third and smallest prong of Burgoyne’s invasion broke down on August 6. Surprised in a bloody ambush, Brig. Gen. Nicholas Herkimer’s New York militiamen and allied Oneidas fought the attacking British and Mohawks under brevet Brig. Gen. Barry St. Leger to a grisly stalemate at Oriskany. While the Americans lost more than half their force—upward of 450 men killed, wounded or captured—St. Leger failed to take his objective, Fort Stanwix. Suspecting the war was a plot by whites to have Indians kill each other off, the Mohawks melted away.

Following the fight at Oriskany, Burgoyne let himself be talked into a march against a Patriot supply depot at Bennington in the New Hampshire Grants (present-day Vermont). His local Tory adviser, former British officer Philip Skene, convinced him that four out of five settler families remained loyal to the Crown. In woeful retrospect Burgoyne later wrote of that folly:

The great bulk of the country is undoubtedly with the Congress, in principle and in zeal; and their measures are executed with a secrecy and dispatch that are not to be equaled. Wherever the king’s forces point, militia, to the amount of three of four thousand, assemble in 24 hours; they bring with them their subsistence, etc., and, the alarm over, they return to their farms. The Hampshire Grants in particular, a country unpeopled and almost unknown in the last war, now abounds in the most active and most rebellious race of the continent.

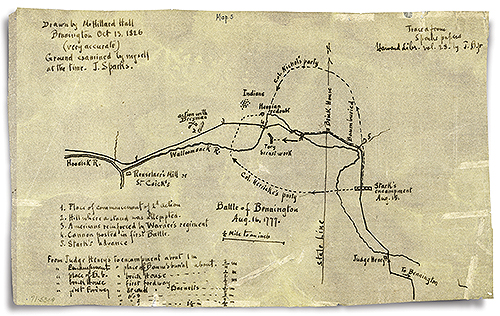

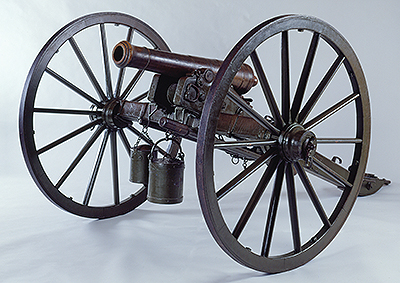

On August 11 Burgoyne sent out Lt. Col. Friedrich Baum, a Brunswicker who spoke no English, at the head a foraging party to collect cattle, horses, carts and wagons for the army. The Baum detachment comprised 434 German infantrymen and dismounted dragoons, 200 Tories, 60 Canadian Loyalists, 50 British marksmen and 14 artillerymen with two 3-pounder cannons. Sent ahead as scouts were some 150 dubious Indians, who only served to alarm the countryside.

The dragoons in their heavy boots clumped along for three days, giving the Americans plenty of time to concentrate their militia and send for reinforcements. On an invitation from provincial authorities, Stark had accepted a commission as brigadier general and assumed overall command of the New Hampshire militia, which included regulars, short-term volunteers and draftees. The draft was not inexorable—those picked could hire a substitute without being defamed. Many were eager to serve under Stark. “I enlisted at Francestown, N.H., as soon as I learned [he] would accept command of the state troops,” militiaman Thomas Mellon noted. “Six or seven others from the same town joined the army at the same time.”

Having mustered some 1,500 militiamen, Stark marched from Manchester to Bennington with Lt. Col. Seth Warner of Green Mountain Boys fame as his guide

On August 8, having mustered some 1,500 militiamen, Stark marched from Manchester to Bennington with Lt. Col. Seth Warner of Green Mountain Boys fame as his guide. “We heard that the Hessians were on their way to invade Vermont,” Mellon recalled. “Late in the afternoon of [a] rainy Friday we were ordered off for Bennington, in spite of rain, mud and darkness. We pushed on all night, each making the best progress he could.”

The rain and mud had also slowed Baum’s expedition. Plagued by Americans who had felled trees across the road to slow the baggage train and artillery, his mixed force never actually reached Bennington. On August 14 they fought with skirmishers from Stark’s forces, who withdrew, but not before destroying a bridge on the approach to the Walloomsac River. Baum’s Brunswickers and Tories fell back on high ground just inside New York and erected two makeshift redoubts of felled trees while awaiting reinforcements. Men on either side of the river struggled to keep their powder dry amid the continuing downpour.

The next morning Burgoyne dispatched Lt. Col. Heinrich von Breymann with 642 Brunswick grenadiers, who ran into similar difficulties with the muddy roads and felled trees. Stark had also sent for reinforcements. Among those answering the call were Massachusetts militiamen under the Rev. Thomas “Fighting Parson” Allen and Warner’s Green Mountain Boys, borderlands tax resisters who’d become rough-and-tumble militiamen. On the morning of August 16, emboldened by the presence of more than 2,000 fighting men under his command, Stark decided to stir the hornet’s nest across the river.

“Stark and Warner rode up near the enemy to reconnoiter, were fired at with the cannon and came galloping back,” Mellon wrote. “Stark rode with shoulders bent forward and cried out to his men: ‘Those rascals know that I am an officer; don’t you see they honor me with a big gun as a salute?’ We were marched round and round a circular hill till we were tired. Stark said it was to amuse the Germans. All the while a cannonade was kept on us from their breastwork. It hurt nobody, and it lessened our fear of the great guns.”

Stark had ordered the circular march in hopes of duping Baum into believing he had men enough to overwhelm the Brunswicker’s trained troops. Afterward, Mellon and a dozen other militiamen were sent to ambush any local latecomers trying to join the Tories. They captured six such stragglers and sent them back to camp under guard. Around 3 p.m. they heard shots and watched the opening engagement from concealment.

“The Germans fired by platoons and were soon hidden by smoke,” Mellon recalled. “Our men fired each on his own hook, aiming whenever they saw a flash. Few on our side had either bayonets or cartridges. At last I stole away from my post and ran down to the battle. The first time I fired, I put three balls into my gun.”

“There, my boys, are your enemies!” Stark cried out, rallying his men to the attack. “They are ours, or this night Molly Stark sleeps a widow!” The precise wording remains in dispute, but the effect was galvanizing.

“We pressed forward,” militiaman Jesse Field recalled, “and as the Hessians rose above their works, we discharged our pieces at them. We kept advancing, and about the second fire they left their works and ran down the hill to the south or southeast. We followed on over their works and pursued them down the hill.” Baum’s feckless Indians beat a hasty retreat, their purloined cowbells jangling into the distance.

The first man to vault Baum’s redoubt was Samuel Safford Jr.—all of 16 years old—whose father was the second-in-command of the Green Mountain Boys and who also had three uncles in the fight that day. Close on Safford’s heels was John Meriam Jr., 20, who took several musket balls through his clothes.

Joseph Rudd, 37, aimed his musket at a stoutly built German, but the weapon misfired. As the German raised his own musket to fire, Rudd knocked the muzzle aside, and the two men grappled. When Rudd managed to draw the German’s sword, the panicked man broke and ran. He didn’t get far. Another American clubbed him dead with a musket butt. Rudd regretted the outcome, as he’d wanted a prisoner, not a corpse.

“After we passed the redoubt, there was no organized battle,” Field recalled. “All was confusion. A party of our men would attack and kill or take prisoners another party of Hessians.…The pursuit was continued until they were all or nearly all killed or taken.”

With the German redoubt subdued, the Americans under Warner turned to the Tory redoubt. Massachusetts militia Col. Joab Stafford noticed a slender old man with white hair in the ranks and asked him to stand sentinel rather than take part in the assault.

“The old man stepped forward with an unexpected spring,” Stafford’s son recalled. “His face was lighted with a smile, and, pulling off his hat in the excitement of his spirit, half affecting the gaiety of a youth, whilst his loose hair shone as white as silver, he briskly replied, ‘Not until I’ve had a shot at them first, Captain, if you please.’”

Inspired by the old man’s gallantry, Stafford personally led his men down a ravine toward the enemy redoubt. To his shock, the ravine emerged within spitting distance of the Tories, one of whom got off a quick shot, hitting Stafford in the foot and dropping him to the ground. Fearing his fall might take the fight out of his men, the wounded colonel sprang to his feet and charged the redoubt. “Clambering to the top of the fort while the enemy were hurrying their powder into the pans and the muzzles of their pieces,” Stafford’s son said, “his men rushed on, shouting and firing, and jumping over the breastworks, and pushing upon the defenders so closely that they threw themselves over the opposite wall and ran down the hill as fast as their legs would carry them.”

Breymann arrived within the hour to find the victorious Americans atop the redoubts, stacking the captured arms and rifling through the supplies. Though Baum had been mortally wounded and the Brunswickers and Tories thoroughly routed, Breymann pressed the attack.

“I have always thought the second to be much the longest and hardest fought action,” Field recalled of the renewed battle. Outnumbered about 4-to-1, the Brunswickers under Breymann felt the pressure.

“Soon the Germans ran,” Mellon recalled. “Many of them threw down their guns on the ground or offered them to us or kneeled, some in puddles of water. One said to me ‘Wir sind ein, Bruder’ [‘We are one, brother’].” The Brunswicker drummers beat a cadence indicating they sought a parley, but Mellon said the Americans didn’t understand. Stark finally called off the pursuit as darkness set in. By then Breymann had been shot in the leg and lost a third of his command dead or wounded. (Faced with another humiliating defeat atop Bemis Heights at Saratoga that October, Breymann resorted to sabering his reluctant men, one of whom shot the obstinate colonel.)

Over five hours of stiff fighting Patriot militiamen had killed 207 enemy soldiers and captured another 700 (including 30 officers) for the loss of about 30 killed and 40 wounded. They’d also seized four cannons and a heap of arms and supplies. The enemy survivors limped back to Burgoyne with news of the catastrophic defeat.

After serving honorably through war’s end and attaining the rank of major general in the Continental Army, John Stark, the hero of Bennington, slipped back into retirement as a simple farmer. Had Benedict Arnold done likewise after securing another upset victory with his headstrong courage at Saratoga, both he and Stark would be remembered as American heroes. MH

John Koster is the author of Hermann Ehrhardt and Operation Snow. For further reading he recommends Memoir and Official Correspondence of Gen. John Stark, as well as The Battle of Bennington, by Michael P. Gabriel, and Battles of the American Revolution, by Curt Johnson.