He was one of those individuals who always seem to be smiling. He always looked as though he was thinking about something humorous or was about to tell you a joke. His name was Henry Harley Arnold, but his friends called him ‘Hap’ because of that ever-pleasant expression. Many of those who served with him in World War II, however, learned that he was impatient, had a temper and could express his displeasure magnificently. As his responsibilities grew, his subordinates found that he would not tolerate incompetence, laziness or poor judgment. But as one staff officer, the victim of one of Arnold’s tirades, said, ‘How can you hate a guy who’s always smiling at you?’

The man who would one day command the mightiest air force ever known was born in Gladwyne, Pa., a suburb of Philadelphia, on June 25, 1886. His father was Dr. Herbert A. Arnold, a physician who served in Puerto Rico during the Spanish-American War. After graduation from high school, Hap decided to enter the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, where he spent an undistinguished four years. He later recalled, ‘I never even made Cadet Corporal.’ He was remembered by his classmates as a leading member of the ‘Black Hand,’ a group devoted to pranks in the middle of the night, for which he walked many punishment tours in full uniform with a rifle.

He graduated in 1907 and was commissioned a second lieutenant in the infantry, although he desperately wanted to be assigned to the cavalry, then considered the most glamorous combat arm of the U.S. Army. In that same year the Army established an aeronautical division of the Signal Corps ‘to take charge of all matters pertaining to military ballooning, air machines, and all kindred subjects.’ But Arnold was unaware of that development at the time, since he was serving two years in the Philippines, much of it on mapping duty.

When his two-year tour was over, Arnold chose to return home by way of Hong Kong, Egypt and Europe. He saw his first airplane in the summer of 1909 in Paris, the fragile monoplane (he described it as a ‘frail, heroic freak’) that Louis Blériot had flown across the English Channel in July 1909. The second plane he saw was at his new post, Governor’s Island, when Wilbur Wright landed there after a flight up the Hudson River. His third encounter with flying machines was at the nation’s first international air meet, held at Belmont Park in 1910, where Wright and Curtiss planes and aircraft from Great Britain and Brazil were competing.

But flying did not make much of an impression on the young infantry officer until he was ‘invited’ to apply for flight training with the Wright brothers at Dayton, Ohio, in April 1911. It wasn’t an order, and he could have turned it down, but his adventurous spirit was stimulated. He accepted the challenge and began flying with instructor Albert L. Welsh that spring. Before their first flight, Welsh pointed out a man in a black derby sitting on a wagon on the other side of the pasture. ‘That’s the local undertaker,’ Welsh said. ‘He comes out every day and drives back empty. Let’s keep it that way.’

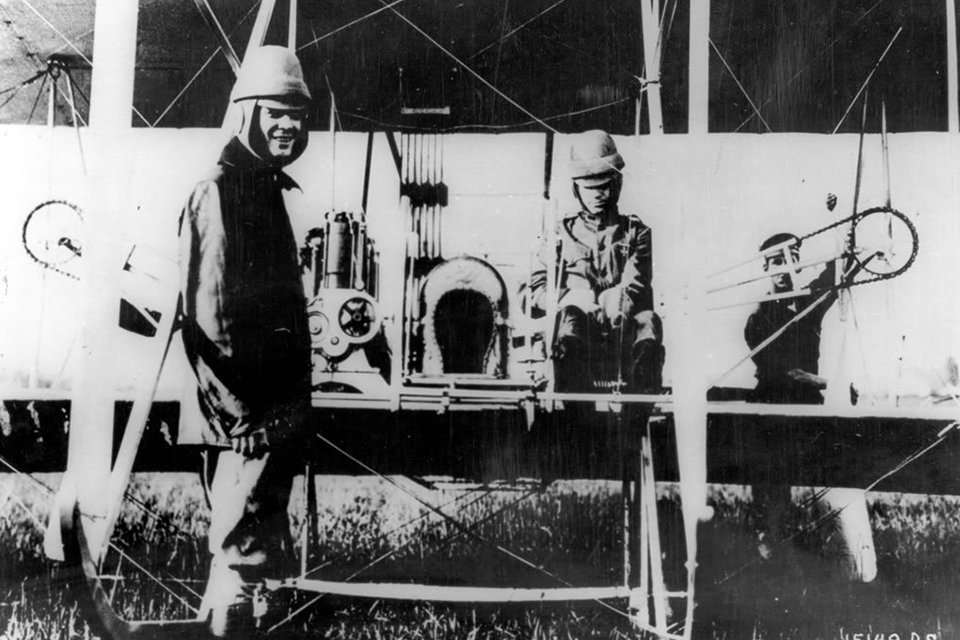

Another officer sent to the Wrights for training was Lieutenant Thomas DeWitt Milling, and the two took their training together. Arnold soloed in 10 days, after 3 hours and 48 minutes of instruction in 28 flights. The lieutenants then reported to College Park, Md., the country’s first military airfield, where they became instructors. At that time, there were only three qualified Army pilots: Arnold, Milling and Lieutenant Benjamin D. Foulois, a Signal Corps officer. Two others — Lieutenants Frank P. Lahm, a cavalry officer, and Frederic E. Humphries of the Corps of Engineers — had also taken training from the Wright brothers as a condition of the contract for the Army’s first aircraft, but they had wrecked the plane and had been ordered to go back to their respective ground units. Lahm returned to flying later. Foulois was ordered to take the wreckage to San Antonio, repair it and teach himself to fly. He did so, with advice by correspondence with the Wrights.

During the early days of military aviation, almost anything a flier did was an aviation first. Lieutenant Jake Fickel hit a target on the ground with a rifle from 100 feet altitude while Milling was piloting their plane. Lieutenant Myron T. Crissy dropped a small bomb on a target during an air meet in California. In June 1912 Arnold laboriously climbed a Burgess-Wright biplane to the unprecedented altitude of 6,540 feet. He also made a reconnaissance flight under simulated combat conditions that took him from College Park to the Army barracks in Washington, D.C., then to Fort Myer, Va., to locate a troop of cavalry, then back to the starting point — all within a 45-minute period. For proving the airplane’s usefulness as a reconnaissance vehicle under operational conditions, Arnold became the first flier to win the coveted Mackay Trophy for outstanding aerial accomplishments, subsequently awarded annually in the name of Clarence H. Mackay, publisher of Collier’s magazine.

During the latter part of 1912, Arnold went to Fort Riley, Kan., where he served as the first military aviator to use a radio to report his observations so artillery batteries could adjust their fire. He had a nearly fatal experience later on when his Wright Model C plane went into an uncontrolled spin. Although he brought the plane out of it, he didn’t know why the spin had happened, and the incident so traumatized him that he developed a fear of flying. In a report to his commanding officer, he admitted, ‘I cannot even look at a machine in the air without feeling that some accident is going to happen to it.’

Accidents and fatalities became such a common occurrence among the 30 or so Army fliers that Congress passed a bill in March 1913 establishing flight pay (35 percent above base pay, later increased to 50 percent) for military aviators. Arnold, however, thought even the infantry might be preferable to continuing to test his luck in the air. He requested a return to an infantry post and was transferred back to the Philippines in late 1913.

In May 1916, now a captain, he returned to the States. At Major William ‘Billy’ Mitchell’s insistence, he reported for duty as a supply officer at a new flying school at San Diego, Calif. He made a 20-minute flight as a passenger in a Curtiss JN-4 Jenny in October 1916 and found it exhilarating. After seven more short dual flights, he conquered his phobia and soloed again.

A brief assignment to Panama as a squadron commander followed, and then it was on to Washington, D.C., when the United States entered World War I in April 1917. Initially promoted to temporary major, he was suddenly jumped to temporary colonel as executive officer of the Signal Corps Aviation Division and later as assistant director of military aeronautics, and he remained in Washington as the senior officer there with wings. The total strength of the Air Division was 52 officers, 1,100 enlisted men and 200 civilians.

There were 55 obsolete aircraft in the inventory, none of them combat planes. Arnold became involved with building up an air arm, from the development and production of aircraft and construction of flying fields to the recruitment and training of flying personnel. The experience was to prove valuable, but Arnold never forgot the frustration he felt because the United States failed to send more than a minimal air force to Europe.

Wartime ranks were temporary, and Arnold reverted to the permanent rank of major in 1920. Meanwhile, he was made commanding officer of Rockwell Field in San Diego. He testified on behalf of Brig. Gen. Billy Mitchell during Mitchell’s 1925 court-martial. As a result, he was ‘exiled’ to Fort Riley, Kan., as the commanding officer of an observation squadron, working with the infantry and cavalry units in seven nearby states. That assignment was followed by a stint in charge of an air depot at Fairfield, Ohio, and another as commanding officer of March Field, Calif., in the grade of lieutenant colonel in 1931.

Arnold’s role at March Field was to convert a primary flying school into two operational groups — one a bomber and the other a fighter unit. There he led in the development of a strategic and tactical air defense doctrine — which was constantly modified but never abandoned through World War II. Concepts of air power were developed during this period that would feature long-range bombers and massed air-striking power. Maneuvers and exercises with bombers and fighters were held in various parts of the country to gain experience in supply, operations and command.

Although the Great Depression had begun, significant aviation technological developments continued to take place in the early 1930s. Monoplanes with retractable landing gear and all-metal construction were the wave of the future for military aircraft. More powerful engines and more efficient propellers were being manufactured, and cockpits were being enclosed. Looking ahead, Arnold undertook the development of new fighter tactics, strategic bombing and cargo airlift. A test of the latter came in the winter of 1932-33, when blizzards of unprecedented intensity swept across the southwestern states, threatening the lives of thousands of Indians in scattered villages throughout the area. Arnold marshaled an assortment of Curtiss B-2s and Keystone B-4s, B-5s and B-6s, and had them loaded with food. Using Indian spotters as guides, the planes ‘bombed’ the snow-buried villages with the life-saving food. The operation continued for several weeks and provided experience that would prove invaluable later on.

The winter of 1934 was a dark period in the development of what had become the Army Air Corps. President Franklin D. Roosevelt canceled all airmail contracts with private operators and directed Maj. Gen. Foulois, chief of the Army Air Corps, to take over the airmail operations. Foulois divided the country into three zones and assigned Arnold to head the western zone, headquartered at Salt Lake City. In his memoirs, Foulois wrote that Arnold and the rest of his men involved knew it would be a difficult assignment. ‘The reason was a simple one, no equipment,’ he said. ‘We did not have the latest instruments, and not very many of our planes had landing, navigation, or cockpit lights. The techniques of flying the newly-developed radio beams were devised by the airline pilots, and our pilots were not very adept at using them.Without instruments and radios, there wasn’t any way for them to practice.’

When the operation was about to begin, Foulois cautioned Arnold and the other two zone commanders not to let their men take chances with the weather, even at the sacrifice of airmail service. Sadly, Arnold had to report three fatalities on training missions because of snow and fog. There were additional fatal accidents because of the lack of training and inadequate equipment. In May 1934, the Post Office Department reissued mail contracts to private operators. The Air Corps was out of the airmail business. And the public learned it could no longer ignore the sad state of its air arm.

While congressional leaders sought to increase the Army Air Corps budget, Arnold organized and led a flight of 10 Martin B-10 bombers from Washington, D.C., to Fairbanks, Alaska, in an 18,000-mile round-trip record formation flight, for which he earned a second Mackay Trophy. The purpose of the Alaskan Flight was the aerial mapping of 35,000 square miles — a project that provided much useful information. It was a dangerous operation, but Arnold completed it without loss of personnel or equipment, demonstrating untiring energy, professional flying skill and fearless leadership. The flight showed that a bomber force could be flown in mass formation over great distances. It also served to restore public confidence in the Air Corps.

In February 1935 Arnold was jumped two grades to brigadier general and put in charge of the 1st Wing of General Headquarters Command at March Field. He commanded three fighter squadrons and three bomber groups and conducted intensive simulated combat exercises. That experience led to his encouraging the development of the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress and Consolidated B-24 Liberator, along with crew training for precision bombing. In January 1936 he became assistant chief of the Army Air Corps in Washington, D.C., and two years later was promoted to major general and appointed chief of the Army Air Corps.

From that point on, Arnold made speeches and wrote articles calling for an adequate air force to counter the growth of German air power that was threatening Europe. He called for the expansion of the Army Air Corps, but it proved to be an unpopular idea. In the mid-1930s, there were no funds for new combat aircraft. But things changed in the fall of 1938, when President Roosevelt called for the production of 10,000 planes in 1940, 20,000 the year after, and later 50,000. Arnold, who had been present when the president made his announcement, later commented: ‘A battle was won in the White House on that day which took its place with — or at least led to — the victories in combat later.’ This directive was Arnold’s license to expand the Army Air Corps. Only 300 pilots were being trained annually prior to 1939. But Adolf Hitler plunged Europe into war that September, and the training figure increased to 3,000 a year in early 1941, and 33,000 after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7. A week later, Arnold was promoted to lieutenant general. Thereafter, he was included in all military meetings in the White House.

Major General Ira C. Eaker, Arnold’s close friend and the leader of the Eighth Air Force during World War II, summarized Arnold’s early war efforts: ‘He began building the French and British planes, incorporating the techniques that they had discovered in the early days of the war, that the Germans and the Russians had developed in Spain. And he used that money for research and development to be sure that we would at the earliest possible time have prototypes of proper bombers and fighters. Without his judgment and wisdom, often complete disregard for regulations and authority, realizing the urgencies, realizing fully that we would be ultimately drawn into the war; this lack of preparedness which was very prominent in 1939 and 1940 could have continued indefinitely. The wisdom of Arnold and the methods he employed closed that gap very quickly.’

ut the road to building a fighting air force was not easy. There was keen opposition from the other services, politicians and industry leaders. Arnold sometimes engaged in verbal brawls with those who could not accept his concepts of air power. The Air Corps was still under the Army at that point, but a reorganization helped the expansion when the Army Air Forces was established as one of three elements within the Army, the other two being the Ground Forces and the Services of Supply.

Arnold called on his friends and anyone he had ever met, looking for competent individuals who could be placed in leadership positions. He also called on the automotive industry for its wholehearted cooperation in converting to aircraft production, and directed the buildup of a huge force of large bombers — Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses and Consolidated B-24 Liberators. Before America entered the war, he also ordered aeronautical engineers to sketch a design for large super bombers and ‘make them the biggest, gun them the heaviest, and fly them the farthest.’ The result was the Boeing B-29, which eventually delivered the atomic weapon that ended the war.

A few days after the Japanese struck Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt called on his top leaders to find some way to retaliate. A plan to fly Army North American B-25 medium bombers from a Navy carrier to bomb Japan was developed, and he called on Lt. Col. James H. ‘Jimmy’ Doolittle to carry it out. Doolittle launched his famed surprise raid on five Japanese cities from the aircraft carrier Hornet on April 18, 1942. Although the raid was successful and no planes were shot down over Japan, 15 of the aircraft were lost when they could not find landing fields in China for a nighttime landing in bad weather. One plane, with its five-man crew, landed in Russia and was interned. Although the mission resulted in only minor damage to enemy war industries, its purpose was psychological, and it succeeded in showing the Japanese they were vulnerable to air attack. As a result, they pulled back units to defend the Home Islands and changed their strategy of conquest. They planned to capture Midway Island in order to extend their frontier closer to the United States and put them in a position to invade Hawaii. The Battle of Midway, fought from June 4–6, 1942, was a disastrous loss for the Japanese; four of their carriers, with hundreds of men and planes, were sent to the bottom.

Meanwhile, the force under Arnold’s leadership began to grow exponentially, from 22,000 officers and 3,900 planes to 2,500,000 men and women and 75,000 aircraft, as he directed the air power buildup on a global scale. His style of leadership was unique for the size of such a force. Dissatisfied with second-hand information, he regularly wrote personal letters to his top commanders and encouraged them to tell him about their problems and how they were handling them. According to Doolittle, ‘These letters back and forth with General Arnold greatly lessened the tendency toward lack of understanding between staff and commands, between top headquarters and the operating units in the field.’

While this may seem an informal way to conduct a world air war, it worked. Headquartered in his office in the newly constructed Pentagon, Arnold was a tough taskmaster who had little patience with anyone who was apathetic or who did not try to overcome obstacles. He bullied industrial leaders and expressed his impatience in colorful language. He knew how to use the press and make persuasive extemporaneous speeches to bring attention to his needs. During his service in California he had met many movie stars. Dozens of actors, including Clark Gable, Jimmy Stewart, Ronald Reagan, William Holden, Robert Cummings, Gene Raymond, Jack Webb and Gene Autry, fell under his persuasive spell and either joined the Army Air Forces or acted in training films. Arnold was also instrumental in persuading sports figures, well-known illustrators and cartoonists, band leaders, playwrights and movie directors to lend their talents to the war effort.

Women were not forgotten in Arnold’s scheme to win the war in the air. When there was a growing pilot shortage, he turned to Jacqueline Cochran to head a program that became known as the Women’s Air Service Pilots (WASPs) to ferry aircraft from factories to shipping points, to tow targets and to flight test aircraft. Although the WASP program was disestablished, Women in the Air Force (WAFs) was its nonflying offspring. To secure assistance with coastal defense, Arnold approved the creation of the Civil Air Patrol — still an official Air Force auxiliary today.

There were many developments in administration and organization as the force grew. The Air Training Command was established, with three major training centers. The Air Transport Command and a worldwide weather service were formed. Pioneering efforts were made in air evacuation and rehabilitation of injured airmen. A global network of radio stations was established linking 52 nations and an Office of Management Control founded to analyze operations in the United States and overseas.

In early 1943, Arnold, now a regular member of the Combined and Joint Chiefs of Staff, participated in a high-level conference at Casablanca to make plans for further operations against Germany and Japan. Afterward, never content with second-hand information, Arnold made a 35,000-mile tour to visit units in North Africa, the Middle East, India and China.

Arnold received his fourth star in March 1943. Shortly after that, he had a heart attack, but he recovered quickly. He subsequently made trips to England and participated in the top-level discussions at Teheran, Iran, led by Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Russia’s Joseph Stalin.

When he returned home from that trip, Arnold’s focus turned to the B-29 then being produced. It would not be used in Europe but would begin operations against Japan from China in July 1944 under Maj. Gen. Curtis E. LeMay, a veteran bomber leader in Europe, who later would become the Air Force chief of staff. Meanwhile, the Allies had landed in Normandy on June 6, 1944. Hordes of Allied aircraft pounded the Germans and by the spring of 1945 had done much to destroy their ability to fight any longer. The theories of strategic air warfare had been proved. Meanwhile, Arnold was appointed to the rank of general of the Army.

Arnold suffered another heart attack in May 1944, but was back on duty and traveling again a few weeks later. He was now very concerned about the tremendously expensive B-29, which was plagued with mechanical problems. Although he was determined to use B-29s effectively against Japan, he wasn’t sure that placing the new bombers in the normal chain of command under either Army General Douglas MacArthur or Navy Admiral Chester Nimitz would get the results he wanted.

Arnold finally settled that question by assuming command of the new bomber force himself. With approval from the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the president, he created the Twentieth Air Force, consisting of the 20th and 21st Bomber Commands. He transferred LeMay and the B-29s from the China-Burma-India theater to the Pacific, with bases in Guam and the Mariana Islands.

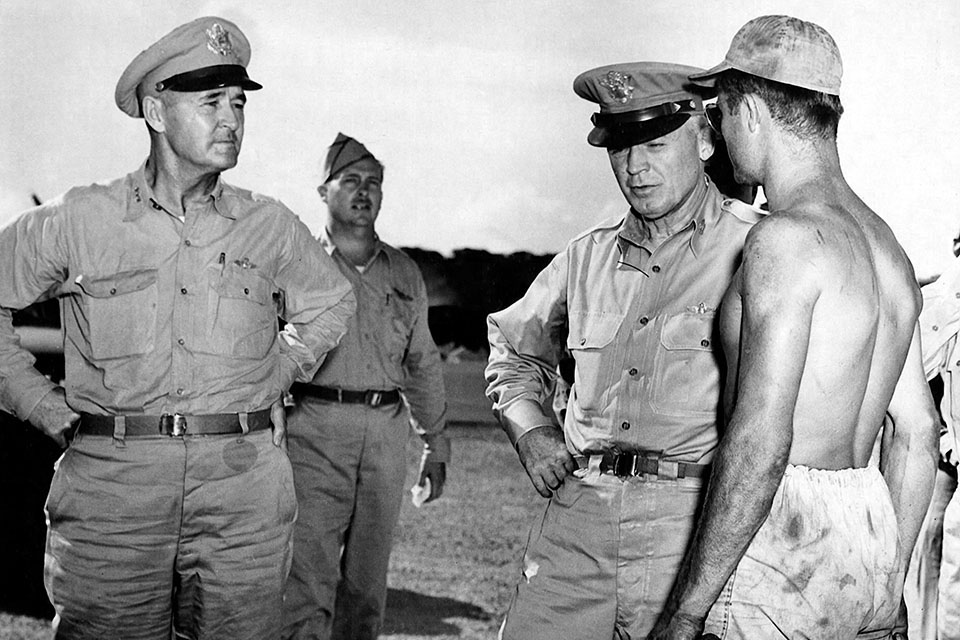

When Arnold made an inspection trip to the Pacific in June 1944, he learned that Admiral Nimitz was resisting the arrival of the Twentieth Air Force in the Pacific theater. On a visit to the Philippines, Arnold found that MacArthur thought he should lead the final drive to Japan. Arnold ignored their claims and complaints and ordered further buildup of the B-29 squadrons. With Arnold’s approval, LeMay converted the operation from high-flying, daylight heavy-demolition bomb attacks to low-level, night fire-bomb attacks.

By August 1, 1945, the major cities of Japan had been devastated, but the Japanese still refused to surrender. On August 6 and 9, the dropping of atomic bombs by two B-29s on Hiroshima and Nagasaki proved the deciding factor. No invasion was necessary, and Japan’s unconditional surrender was accepted on August 14.

Four days later Arnold announced that he intended to retire, but he continued to preside over the Army Air Forces. He wrote an article titled ‘Our Power to Destroy War’ and argued for a continuing national research and development effort on every scientific front, not just aeronautics. ‘What we will need,’ he wrote, ‘is an adequate, well-trained, fully equipped force of whatever kind is necessary to use the new weapons and devices properly.’

Under Arnold’s command, the U.S. air arm had grown from 22,000 officers and enlisted personnel with 3,900 aircraft to nearly 2.5 million men and 75,000 planes. But he had already planned for the future, though he would not be a part of it. He called on Theodor von Karman to head a committee of scientists to set up a plan of research for the next quarter or half century and project how inventions such as the jet engine, radar and rockets could be best used for national defense. Arnold told Karman that he did not want the Army Air Forces ever again to be caught unprepared, as it had been in 1939.

Arnold flew to South America in January 1946, but returned early because of health problems. In February he called his headquarters personnel together in the Pentagon and gave a valedictory talk in which he reviewed the growth of the air forces and then spoke of the promise of the future, including supersonic aircraft and space exploration.

Arnold retired officially on June 30, 1946, having set plans in motion that would eventually lead to an all-jet air force, one equal in status with the Army and the Navy, under a secretary of defense. Just as Billy Mitchell had done so many years before, Arnold had lobbied tirelessly for such a reorganization. It finally came about on September 17, 1947, the birth date of the U. S. Air Force.

Although Arnold had retired from the service three years before, he was appointed the first (and so far only) general of the Air Force, a permanent five-star rank, on May 7, 1949. During his long career he had written several books, including some intended to create interest among youth in flying. His autobiography, Global Mission, an accurate account of his life and Air Force activities, was released in 1949, just as the Berlin Airlift was concluding and before the beginning of the war in Korea. In it, he cautioned: ‘The principles of yesterday no longer apply. Air travel, air power, air transportation of troops and supplies have changed the whole picture. We must think in terms of tomorrow. We must bear in mind that air power itself can become obsolete.’

Arnold survived at least five heart attacks during his adult life. His heart finally gave out on January 15, 1950, at his ranch home near Sonoma, Calif. He was 63 years old and had served his country for 42 of those years. Although he had never fired a gun or dropped a bomb in combat, he had led the development and employment of the largest air force in the world. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery with the full military honors he so richly deserved.

This article was written by C.V. Glines and originally published in the September 2000 issue of Aviation History. For more great articles subscribe to Aviation History magazine today!