Jesse Owens, the greatest track and field athlete in the history of America and probably the world, had his finest hour when the world needed him most. In 1936, as Adolf Hitler was staging the Olympic Games in Berlin as a testament to Aryan supremacy, Owens won four gold medals, shattered Nazi racial theories, and opened the eyes of millions of his countrymen back in America.

James Cleveland Owens was born in 1913 in Oakville, a town in northern Alabama. He got the nickname “Jesse” when a teacher asking his name misheard the youth’s drawled response, “J.C.”—the name was spelled both Jesse and Jessie in newspaper and magazine accounts of Owens’s exploits. He was nine when his family moved to Cleveland, Ohio, as part of the Great Migration of blacks to northern cities.

As a senior at East Technical High School, he drew headlines at the 1933 National Interscholastic Games in Chicago, Illinois, where he tied the world record of 9.4 seconds for the 100-yard dash. The week before, he had set a broad jump record of 24’-9 ½”.

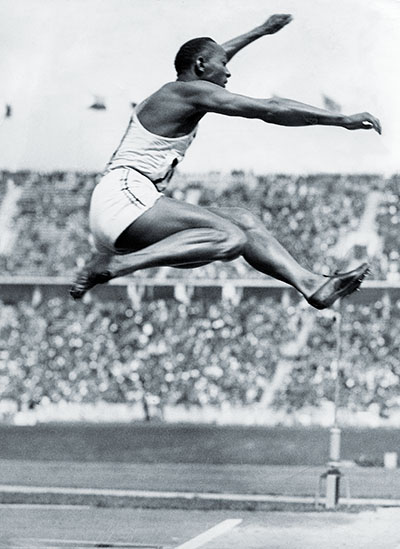

Enrolling at Ohio State as a bona fide star, Owens nonetheless received no scholarship money. He worked his way through school doing odd jobs. On May 24, 1935, at the Big Ten Conference Championships in Ann Arbor, Michigan, Owens put on the most spectacular show ever seen in American college athletics. He set world records in the long jump, 220-yard sprint, and 220-yard hurdles and tied the world record for the 100-yard dash. This extraordinary performance propelled him to Berlin the following summer.

Owens’s glory years were chronicled for the first time in a recent film, Race, from English director Stephen Hopkins and starring Stephan James (John Lewis in Selma).

Race skips Owens’s childhood, introducing him as a high school phenom in Ohio and treating him as saintly. However, in reality Jesse Owens was an immature young man who waited three years before marrying the mother of his daughter—and then only under pressure. James gives us a portrait of Owens far from the cool and assured Jackie Robinson, America’s other great black sports pioneer, played by Chadwick Boseman in 42.

Though he’s cocksure of his talent, Owens is tentative about making his way in a white-dominated world. He needs the guidance, on and off the track, of his college coach, Larry Snyder, played with an unexpectedly abrasive swagger by Jason Sudeikis. A longtime sketch comic on Saturday Night Live, Sudeikis is a revelation. He has played mostly in romantic and screwball comedies, giving no indication that he could carry a dramatic role of this weight. It’s a bold performance, and Sudeikis isn’t afraid to show Snyder as a bigot. He is desperate for a track and field ringer but doesn’t need the aggravation of Owens’s race.

The scenes of the two working toward an understanding—Snyder was a track star whose own immaturity ruined his chances to make the 1924 Olympics in Paris—ring true. Another real-life relationship that works on screen is Owens’s brief association with Carl “Luz” Long, a German athlete who risked Nazi wrath by befriending Owens and offering advice during the games.

The story picks up steam in Berlin, but Race suffers from having too much story to tell, and so simplifies or glosses over certain facts. Jeremy Irons gives a sly performance as the controversial dark lord of American athletics, Avery Brundage, head of the American Olympic Committee in 1936 and later of the International Olympic Committee. Irons’s Brundage is smart enough to play along with Nazi politics, particularly when his company profits by building Berlin’s Olympic facilities. Race, though, makes him seem conflicted when, after Owens humiliates the Nazis by winning three gold medals, Brundage caves to their demands that he pull two Jewish American athletes from the final track competition.

The film equivocates on filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl, played by Carice van Houten (Melisandre in Game of Thrones). Riefenstahl’s 1935 documentary, Triumph of the Will, was the epitome of Nazi propaganda. In 1936, she was commissioned to film the Olympics as a tribute to Hitler’s Third Reich.

We do know that she did not film the long jump event that Owens won, but it’s not clear whether she demurred on orders from Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels. Whatever the reason, she restaged the event, allowing Owens to recreate his triumph.

Was Hitler, as the movie suggests, incensed by this black American athlete’s showing? Race has Owens being escorted to Hitler’s box to find that the dictator, furious at seeing German runners lose to a black man, has stomped off. Certainly Hitler staged the Olympics to hype his master race, but there’s no evidence that he boycotted Owens. Witnesses said Hitler, seeing storm clouds, left the stadium well before Owens’s events, assuming weather would delay them. Owens flatly said, “Hitler didn’t snub me”—though later that year at a Republican Party rally in Kansas City, he told reporters, “It was our president who snubbed me. The president didn’t even send me a telegram.” No one knows why President Franklin Roosevelt failed to acknowledge Owens’s achievement.

Life after the Olympics often disappointed Owens. To earn a living, he resorted to making guest appearances at baseball doubleheaders and competing with horses. “People say that it was degrading for an Olympic champion to run against a horse, but what was I supposed to do?” he wrote in his 1972 memoir, I Have Changed. “I had four gold medals, but you can’t eat four gold medals.”

Owens did make investments, but by the 1960s he was working at a gas station. He filed for bankruptcy; the federal government prosecuted him for tax evasion.

But there was also good news.

Perhaps as reparation for the tax prosecution, the administration of President Lyndon Johnson named the athlete a goodwill ambassador, and Owens toured the world speaking in countries that better remembered his Olympic triumphs than many Americans did. In retirement, Owens took pride in noting that he was well off enough to own racehorses like those he once had competed against.

Official appreciation for the track and field immortal came late. In 1976 President Gerald Ford awarded Owens the Medal of Freedom. A heavy smoker, Owens died of cancer in 1980. In 1990, President George H.W. Bush awarded him a posthumous Congressional Gold Medal.

On June 29, 1996, the Jesse Owens Memorial Park and Museum in Oakville, Alabama, Owens’s birthplace, was dedicated as runners carried the Olympic torch through the grounds en route to that summer’s games in Atlanta.

A bronze, torch-themed plaque at the park carries an inscription composed by Alabama poet Charles Ghigna: May this light shine forever as a symbol to all who run for the freedom of sport, for the spirit of humanity, for the memory of Jesse Owens. ✯

This story was originally published in the July/August 2016 issue of American History magazine. Subscribe here.