“Wild Bill” and “Buffalo Bill,” each dressed in gray, had a snack while chasing Confederates under Sterling Price

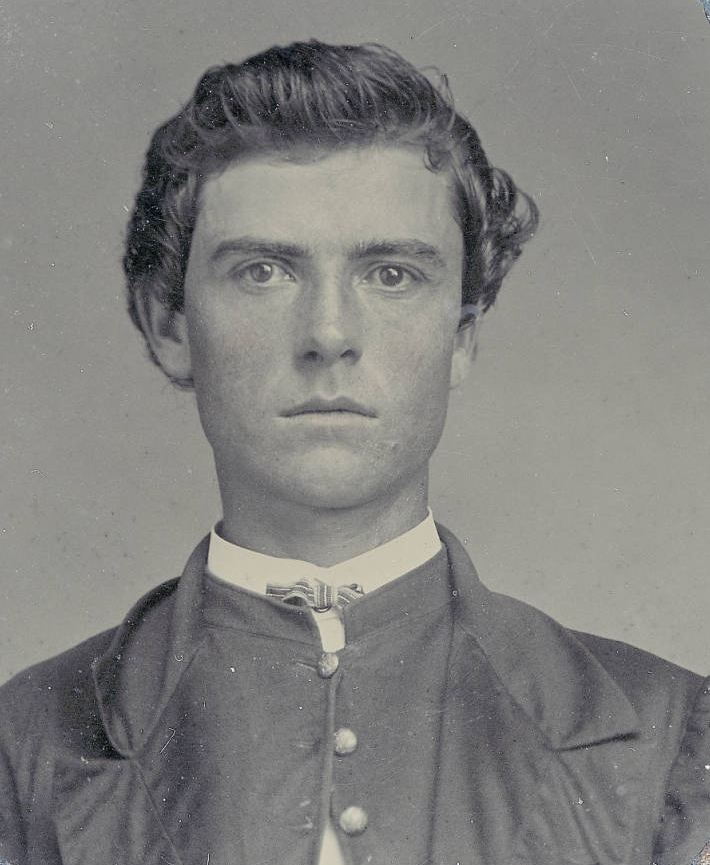

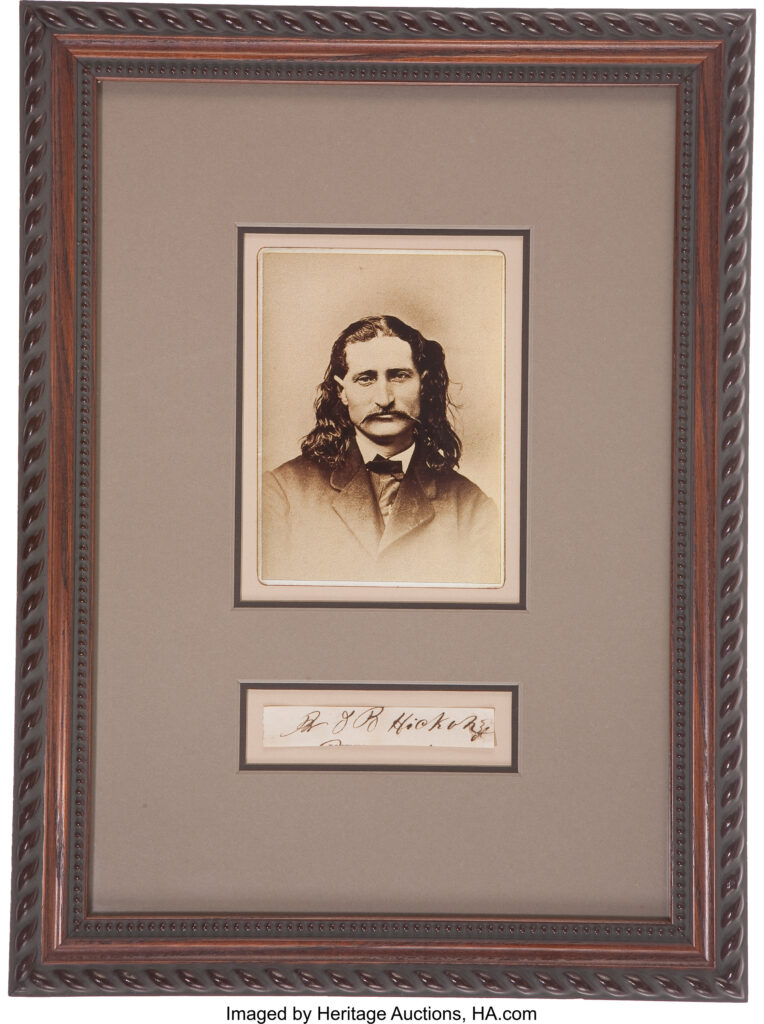

In early October 1864, two budding Wild West luminaries happened to meet in the middle of Confederate Maj. Gen. Sterling Price’s invasion of Missouri, what became known as “Price’s Lost Campaign.” William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody was a trooper with the 7th Kansas Cavalry that fall; James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok was a scout working for either Union Brig. Gen. John McNeil or Brig. Gen. John Sandborn (depending on the account you read). Cody related the incident in his autobiography The Life and Adventures of Buffalo Bill:

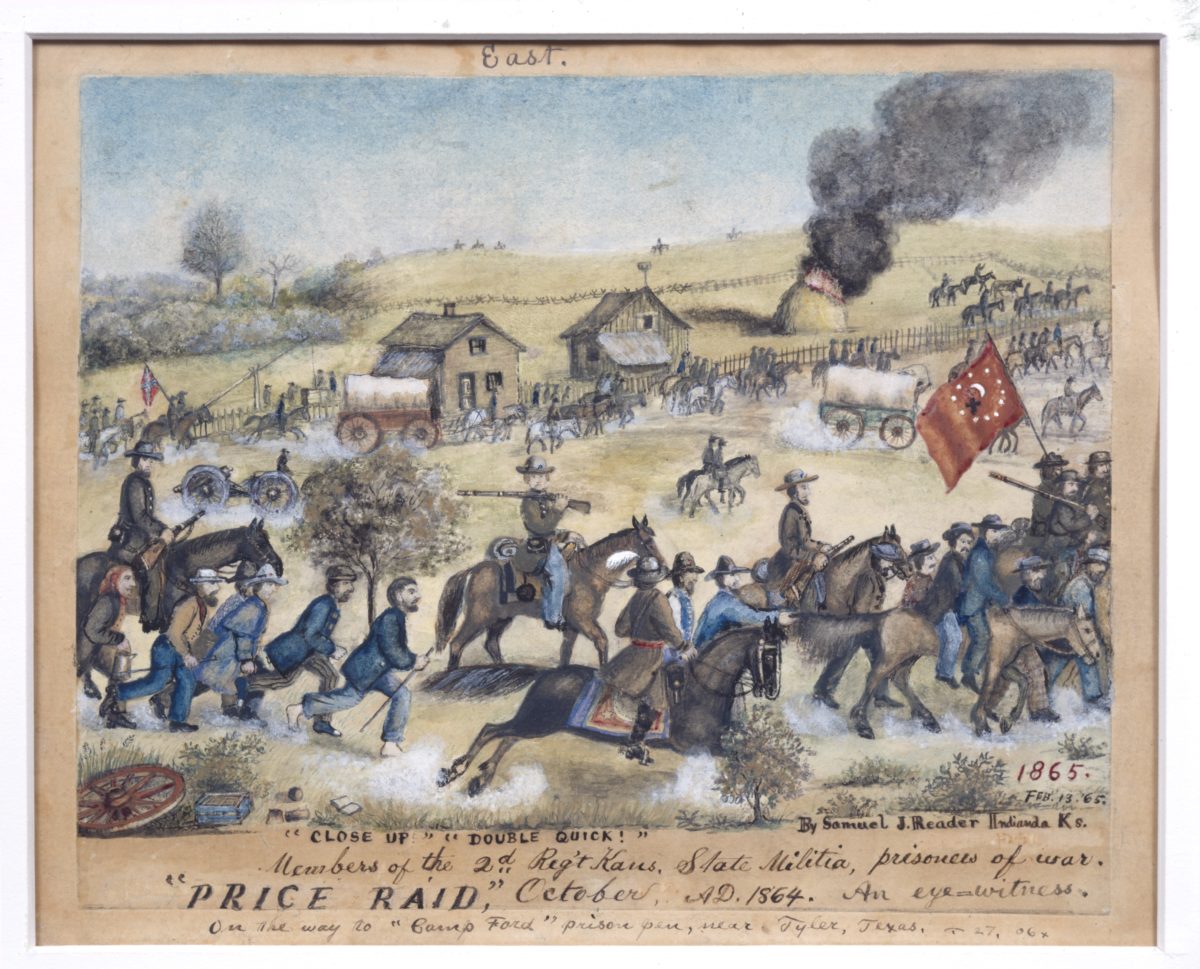

After skirmishing around the country with the rest of the army for some little time, our regiment returned to Memphis, but was immediately ordered to Cape Girardeau, in Missouri, as a confederate force under General Price was then raiding that state. The command of which my regiment was a part hurried to the front to intercept Price, and our first fight with him occurred at Pilot Knob. From that time for nearly six weeks we fought or skirmished every day.

I was still acting as a scout, when one day I rode ahead of the command, some considerable distance, to pick up all possible information concerning Price’s movements. I was dressed in gray clothes, or Missouri jeans, and on riding up to a farm-house and entering, I saw a man, also dressed in gray costume, sitting at a table eating bread and milk. He looked up as I entered, and startled me by saying:

“You little rascal, what are you doing in those ‘secesh’ clothes?” Judge of my surprise when I recognized in the stranger my old friend and partner, Wild Bill, disguised as a Confederate officer.

“I ask you the same question, sir,” said I without the least hesitation.

“Hush! sit down and have some bread and milk, and we’ll talk it all over afterwards,” said he.

I accepted the invitation and partook of the refreshments. Wild Bill paid the woman of the house, and we went out to the gate where my horse was standing.

“Billy, my boy,” said he, “I am mighty glad to see you. I haven’t seen or heard of you since we got busted on that St. Louis’ horse-race.”

“What are you doing out here?” I asked.

“I am a scout under General McNeil. For the last few days I have been with General Marmaduke’s division of Price’s army, in disguise as a southern officer from Texas, as you see me now.”

“That’s exactly the kind of business that I am out on today,” said I; “and I want to get some information concerning Price’s movements.”

“I’ll give you all that I have,” and he then went on and told me all…he knew regarding Price’s intentions, and the number and condition of his men. He then asked about my mother, and when he learned that she was dead he was greatly surprised and grieved; he thought a great deal of her, for she had treated him almost as one of her own children. He finally took out a package, which he had concealed about his person, and handing it to me said:

“Here are some letters which I want you to give to General McNeil.”

“All right,” said I as I took them, “but where will I meet you again?”

“Never mind that,” he replied, “I am getting so much valuable information that I propose to stay a little while longer in this disguise.” Thereupon we shook hands and parted.

The sort of stuff that gets worked into a movie, don’t you think?

Historian Mark Lause argues in Price’s Lost Campaign that this exchange likely took place on October 4 or 5, 1864, east of the Gasconade River. Regardless of the exact time and place (or even if it happened at all), it’s a telling example of the legend and lore that forever binds the Civil War and postwar expansion of the West.

This post, adapted for print, originally appeared on Craig Swain’s blog “To the Sound of the Guns.” It appeared in the May 2020 issue of America’s Civil War.