Abner Doble spent his life trying to turn boiling water into speed—and success

IN 1923, A CALIFORNIA-BORN, MIT-educated engineer introduced an automobile that surpassed Henry Ford’s market-leading gasoline-powered Model T by every mechanical measure—and without an internal combustion engine. Abner Doble’s Model E, which ran on steam, could travel hundreds of miles on a 17-gallon tank of water plus 26 gallons of kerosene to heat the car’s boiler. In contrast, a Model T could go only 200 miles on 10 gallons of gasoline. A Ford needed 40 seconds to accelerate to its top speed of 40 mph. Once a Model E had steam up, it could hit 60 in less than 10 seconds.

Steam had been powering American automobiles since the early 1900s. As the 20th century unfolded, Stanley Motor Carriage Company of Newton, Massachusetts, was producing one of the best-selling American cars, the Stanley Steamer. In 1906, a Stanley reached a record-setting 127 mph.

A steam power plant may appear complicated, but it operates on a very simple principle: boil water to make steam that propels the vehicle (see “Doble Talk With Jay Leno,” below). Water, fed from a tank, fills a boiler like a kettle or a steam generator arranged as a seamless, circular tube. To heat the boiler, a spark plug sets afire a mixture of air and fuel in the carburetor that ignites the firebox. The firebox brings the boiler’s contents to at least 500° Fahrenheit, generating enough steam pressure to drive a set of pistons. Gears connect the pistons to the rear axle, making the wheels turn.

Initially the challenge was how to light the boiler—a complex, dangerous manual task. A boiler could need half an hour to generate a head of steam. Early steamers vented spent steam as water vapor, quickly emptying their water tanks. A steamer could get 100 miles to a tank but more often at the 50-mile mark a driver had to find a creek or horse-watering trough from which to siphon water using a garden hose and—what else—a steam-powered pump. Few drivers carried containers of spare water.

However, a steam engine ran more simply and efficiently than its internal combustion counterpart. Doble’s car had only 22 moving parts—11 in the engine, compared to a Stanley Steamer’s 32, and a Model T’s many hundreds of pieces. A steamer needed neither clutch nor transmission, simplifying the power train. The kerosene a Model E used to boil water burned so cleanly as to be virtually non-polluting—the only effluent was water vapor. Even today a Doble can pass California’s strict emissions test, the toughest in the nation.

The story of how Abner Doble and his brothers brought out an innovative vehicle most people have never heard of is a remarkable tale of genius and determination—as well as a cautionary saga of managerial incompetence, blind ambition, and criminal guile.

Born in San Francisco on March 26, 1890, Abner Doble grew up in a mechanically minded family. His grandfather and namesake had made a fortune during the California Gold Rush manufacturing tools for miners. His father, William Ashton Doble, made a second fortune perfecting and patenting the power-generating Pelton-Doble waterwheel. Raised in prosperity, Abner and younger brothers William, Jr., John, and Warren grew up in the age of steam, when boiling water not only powered most factories but trains, ships, and a newfangled invention called the automobile. In addition to market leader Stanley, White Motor Company and Locomobile sold steamers priced as low as $650 in the early 1900s, rising to as much as $3,950 in 1924. Of 4,200 autos manufactured in the United States in 1900, only 22 percent were gas-powered; 37 percent were electric. The majority of vehicles—40 percent—ran on steam.

Abner began his mechanical apprenticeship at eight, working after school for a nickel an hour in his grandfather’s San Francisco machine shop. In 1906, as a high school freshman, the oldest Doble boy collaborated with his brothers to begin constructing a steam-powered automobile in their parents’ basement. Assembling a chassis and engine of their own design, the boys cannibalized a wrecked White steamer. The jalopy’s engine ran on the rough side but the project hooked the Doble brothers on steam.

In 1910, Abner enrolled at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. A classic example of a certain technocratic type, Abner Doble was driven, stubborn, and excessively confident, but also sufficiently self-aware to be able to recognize his own most regrettable qualities: “high-strung and sensitive…impulsive though reasonably well controlled…(and) difficulty hiding impatience with…hypocrisy or shallow reasoning.”

One of the MIT freshman’s extracurricular activities was a visit to Stanley Motor Carriage, a few miles west in Newton, to lobby for a concept of his: a condenser designed to capture and recirculate steam that Stanley cars now expelled into the atmosphere. This would dramatically increase a steamer’s range. Company executives brushed the lad off, but, confident in his idea, Abner dropped out of MIT after a semester—he later claimed to have put in two years—and with his folks’ financial support partnered with brother John to open a machine shop in Waltham, Massachusetts. Intent on surpassing the Stanley standard, the two rethought every aspect of automotive steam technology.

The result, completed in 1912, was a prototype, the Model A, which incorporated an early version of that innovative condenser and led to the Model B, known as the Doble Steam Carriage. Even discounting for ballyhoo—and Abner Doble was big on that—the Model B was a step up among steamers, surpassing even the leading-edge Stanley that held the speed record. But to put the Doble Steam Carriage into production, Abner needed capital.

In 1912 it wasn’t clear whether steam or internal combustion would prevail as the ranking automotive power source. The internal combustion engine had hardly been a success when it debuted. Americans considered early gas-guzzlers noisy, noxious, and difficult to operate. Drivers had trouble mastering a new contraption, the clutch, for changing gears, and a vehicle’s crank starter could break a careless man’s arm—drawbacks that, along with many others, convinced the Doble brothers they could outdo Ford.

Gas-powered vehicles acquired an important new advantage in 1912, when General Motors introduced a key-operated electric starter, rendering the crank obsolete. This cast in sharp relief the classic steamer problem: the long wait between ignition and having enough steam to hit the road.

First John, then Warren and William arrived. The brothers focused on shortening their machine’s time to steam. John had the breakthrough insight—a steam generator that could heat water in its tubes to 750° F in less than 90 seconds. Sales materials claimed the car could travel 1,200 miles on 25 gallons of water and 25 gallons of kerosene.

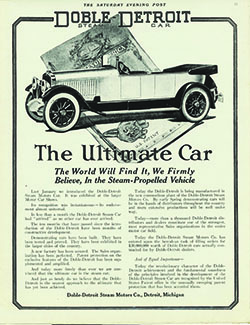

Abner, that master of ballyhoo, soon had the automotive press raving about the Doble-Detroit for offering the convenience of petroleum power with simpler mechanics and superior speed and range. In fall 1916, The Automobile called the Doble-Detroit “strictly up to date.” Scientific American featured a detailed cutaway of the mechanics.

Abner formally introduced the Doble-Detroit at the January 1917 National Automobile Show in New York City. Organizers relegated the Doble, the 100-vehicle event’s only steamer, to a remote fourth-floor location.

Still, the car greatly impressed onlookers. In addition to a big, sleek body, spoke wheels, and spacious interior, the auto had only four controls: steering wheel, brake pedal, reverse pedal, and a small manual throttle nestled inside the steering wheel. The Doble-Detroit came configured as a roadster and also

as a four- or seven-seat sedan, with each buyer able to select bodywork, trim, paint, and interior. Abner hesitated to fix a price, which varied by order, but the Doble-Detroit was not a bargain-basement flivver.

Nevertheless, commercial interest ballooned. A Fort Worth, Texas, car dealer said he wanted 500 Doble-Detroits; a San Francisco outfit, 1,000. By April 1917, General Engineering had orders for 11,000 cars and more than 5,000 cash deposits. The company planned to start delivering cars in early 1918—until President Woodrow Wilson declared war against Germany, and America rearranged its industrial might to support an army fighting in Europe.

War or no war, by that September General Engineering had leased a 52,000-square-foot factory in Detroit and engaged an advertising agency to promote its brand. However, the brothers quickly found that they had little grasp of mass production, especially in a wartime economy.

Abner blamed the government for redirecting steel to military uses, but the Doble-Detroit had other woes. The 11 vehicles that Doble-Detroit Steam Motors did deliver proved sluggish and unreliable. Doble-Detroits tended to pop unexpectedly into reverse. Finicky boilers caused breakdowns.

And Abner was a publicity hog, glossing over his brothers’ contributions. His self-aggrandizement wore on John, the most mechanically gifted Doble. John sued Abner for patent infringement. Their father sided with John, giving interviews and taking out ads on his younger son’s behalf. Amid growing enmity, Abner sold his General Engineering shares in 1919 and returned to San Francisco. Later that year Doble-Detroit closed its doors.

His company bankrupt, the Doble-Detroit discredited, and snarled in a fraternal patent dispute, Abner quit the car business. But when John, 28, died of lymphatic cancer in 1921 the surviving brothers reconciled and formed Doble Steam Motors Corporation of San Francisco. The brothers broke ground on May 26, 1923, at 4053 Harlan Street in Emeryville, California.

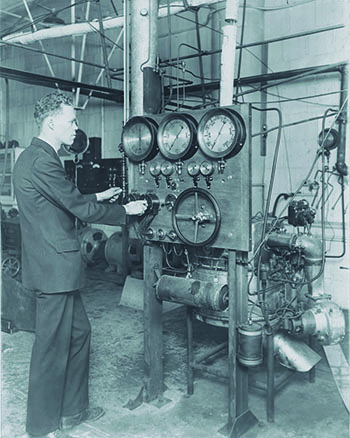

The factory building, which still stands —expanded to three stories and now converted into artists’ lofts—devoted the ground floor to parts and service and the second story to a machine shop, assembly area, and “Experimental Department.”

The brothers’ Model E aimed for the luxury market. Priced at about $18,000—$9,000 for the chassis plus $9,000 for a custom body—an E cost the equivalent of $250,000 in today’s dollars. Swells, especially Hollywood high-rollers, swore by the car. Boasting a compound four-cylinder engine driven by a steam generator, the Model E boasted a 100,000-mile engine warranty. With alcohol keeping its water supply liquid, the E reliably started even in freezing weather—a challenge for a Model T—and a new electric starter had steam up in 90 seconds. An E could accelerate smoothly from 0 to 75 mph in 10 seconds, pressing occupants into their seats with 1,000 lbs. of torque and outrunning any Packard, Cadillac, or Lincoln.

In addition to speed, the Model E boasted craftsmanship. An E rolled off the Emeryville line as a chassis fitted with drive train and mechanical components. Workers added a makeshift seat and instrumentation. Company drivers steered the bare-bones assemblages 500 miles south to the Walter M. Murphy Coach Works in Pasadena. Murphy’s technicians installed English-made Rudge Whitworth wire wheels, a Bosch electrical system, nickel-silver headlights with Bausch & Lomb lenses, and Zeiss reflectors, then custom-tailored body, trim, and upholstery to each buyer’s wishes.

The Los Angeles Evening Express called the Model E “a motorcar that has shattered all conception of automobile performance,” and the Emeryville factory was poised to produce 300 vehicles a year, with annual sales forecast at 1,000. A year after the Dobles broke ground for their factory, America’s last major steam-powered auto manufacturer, Stanley, closed. The brothers had the steamer market to themselves, yet once more mass production eluded them. Building cars one at a time, Doble Steam Motors made Model Es for seven years, selling to such celebrities as actors Buster Keaton and Wallace Beery and Hollywood mogul Joseph Schneck, who purchased one for actress-wife Norma Talmadge. A maharajah bought a Model E for tiger hunting in India. He had Murphy install taps for beer and ice water. In Texas, 19-year-old tool-and-die heir Howard Hughes was clocked doing 132 mph in the desert at the wheel of his 1925 Model E.

The brothers planned a $15 million expansion to accommodate a $2,500 “economy” model, the Simplex. But again the Dobles bobbled the basics. The Simplex, meant to broaden their brand’s appeal and generate much-needed income, never got past the prototype stage.

And the company’s main model had chronic problems. The 5,600-lb. Model E proved heavy, hard to steer, and difficult to stop since, like most cars of the day, it lacked front brakes. Then there was Abner’s perfectionism. He not only insisted on the finest, most expensive components—he couldn’t stop tinkering. No two Model Es were identical. Every time they sold a Doble, the brothers lost money.

Abner also ran into legal trouble. In 1923’s bull market, Doble Motors had had no difficulty selling $1 million in shares. But the California state commissioner of corporations barred the company from issuing additional stock until 50 cars had reached the road and were still running six months after being sold. The court’s examiner had concerns about the Dobles’ production plans, but expressed unreserved approval of their vehicle.

Desperate for money, Abner oversaw or ignored company agents who illegally sold an additional $400,000 worth of stock. Before the New Year, California authorities indicted Abner and three associates on five counts of securities violations. In 1926, Superior Judge Michael J. Roche ruled Abner personally liable for ensuring the company paid 30 cents on the dollar to stockholders who had bought shares sold fraudulently. Though his codefendants pleaded guilty and testified against him, and though during the trial the company books went missing, Abner clearly made a positive impression on jurors, who asked that Judge Roche show the defendant “extreme mercy.” The judge sentenced Abner to

one to five years in San Quentin. Appeals kept him free until the California Supreme Court reversed Judge Roche’s decision on grounds that he had improperly instructed the jurors. Bad publicity, legal costs, and the crash of 1929 prevented Doble Motors from issuing more stock, the start of a fatal decline punctuated by tragedy. In 1930, while his father was in New Zealand promoting steamers, Abner Doble Jr., 10, died in a fall. The following year, Doble Motors, which had built and sold 42 Model Es, was forced to liquidate its assets.

Even so, Abner Doble remained committed to steam. He devoted the rest of his life to evangelizing on behalf of steam and consulting in the United States and Europe.

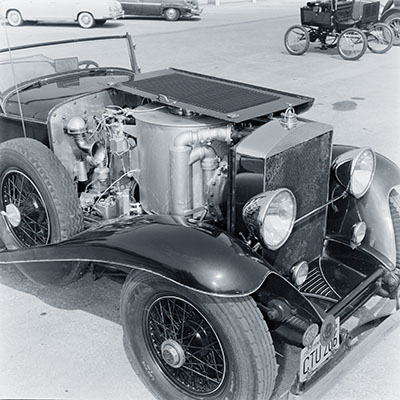

In 1951, chainsaw mogul Robert Paxton McCulloch hired Doble to develop an engine for his newest project—a steamer called the Paxton Phoenix. McCulloch even bought Doble’s personal car, the Model E-24, to analyze its workings. McCulloch got as far as transplanting Abner’s engine into a 1953 Ford before scrapping the experiment.

Abner, 70, was living in Santa Rosa, California, when he died of a heart attack on July 16, 1961. The Doble company’s high standards and minuscule output has paid off—on the rare occasion that a Model E comes up for sale, well-heeled auction bidders push the price to seven or eight figures.✯

Doble Talk With Jay Leno

Steamers like the Doble are great show-off cars. Your friends might know a little about cars and engines but chances are good they have no idea how a steamer works, so you get to be the expert. And people aren’t amazed at how fast you got there—they’re amazed that you got there at all. They used to call steam “the hand of God” because it generates such tremendous torque, the force that turns a wheel. Steam ruled from 1803 until around 1910, and the Doble came out in the 1920s, so it is something of a throwback, although a very refined throwback. The Doble is the only steamer that starts at the turn of a key. A steamer creates and stores power in the form of steam. Stanleys and other steamers use 212o steam. Their boilers heat all the water at once, like giant teakettles. With a Stanley, you light the pilot and have a cup of coffee or two, by which time you have steam up. Dobles are ready to go right away because they superheat water to 750o or 850o with a steam generator, which is like a tankless water heater. Imagine a long, red-hot tube. You put water in one end and instantly steam comes out the other end. The Doble steam generator has 600 feet of tubing in a coil, from ¾ of an inch in diameter down to half an inch. The fire generating that steam burns at 3,000o. At that temperature, all the fuel burns, so few unburned emissions go into the air. A drop of water superheated under pressure expands 2,500 times. It explodes. That’s where a steam engine gets its power. It’s the opposite of an internal combustion engine, which burns fuel to generate power in four strokes: intake, compression, combustion, and exhaust. To move a vehicle, you have to multiply the torque those four strokes produce, and for that you need a clutch and a transmission. A steam engine has no clutch or transmission. It simply pushes pistons up and down, and the pistons are connected to the wheels. The power is right there. It’s pure. There’s no neutral, no need to change gears—like one of today’s electric cars. The acceleration is constant. As Marlon Brando says in The Wild One, you just go. A Doble is interesting to drive. Like all cars of its era, it’s maintenance-intensive. I have a 1918 Cadillac whose manual lists things to be done, like turning the grease caps to lubricate the chassis, every 125 miles. And manufacturers of these cars presumed buyers were wealthy. The Doble owner’s manual is always referring to “your man,” as in “…Have your man do this…” and “…Have your man do that…” Also like most cars of the period, the Doble is big and heavy. When I’m out in one, the phrase “road-hugging weight” comes to mind—a Doble weighs about 5,600 lb. Originally they didn’t have front brakes. That was not a problem in the `20s and `30s, when the speed limit was 45 or so, but to be able to stop I installed Corvette front disk brakes on mine. Driving a Doble might not impress someone today, since modern cars are so quiet. But old time cars backfired and had leaky mufflers. Their engines were noisy, and had exhaust cutouts that you opened for acceleration, which made even more noise. In the early days, you started a car with a crank that could break your arm. The Doble and other steamers have none of those drawbacks—although they do have drawbacks of their own. To operate one you need three fluids: water for steam, fuel to make steam, and steam oil, a thick lubricant added to the water in the steam generator. . Driving a Doble feels about like driving one of today’s electric cars. You just open it up and move. It’s effortless. Among my cars, it feels most similar to the Tesla P90D, which interestingly, with its batteries, weighs about 5,000 lb. As you’re driving, you’re watching the gauges. They show steam pressure and temperature, which both should be in the 750-850 range—that is, 750 to 850 pounds per square inch of steam pressure and 750o to 850o Fahrenheit. You control your speed with the throttle, a small wheel set inside the steering wheel. The Doble throttle is like the spigot on the side of your house, which is a screw valve. You turn one way to open, the other way to close. That little wheel controls the steam and the acceleration. There’s no shifting. In many ways, my Doble feels like a modern car—quiet, solid, and I can go 70 mph with no problem, whereas with any other car from 1925 40 or 45 mph is the end of the world. —Jay Leno, a comedian and car collector, hosts Jay Leno’s Garage on CNBC and YouTube. For more on Dobles, click here