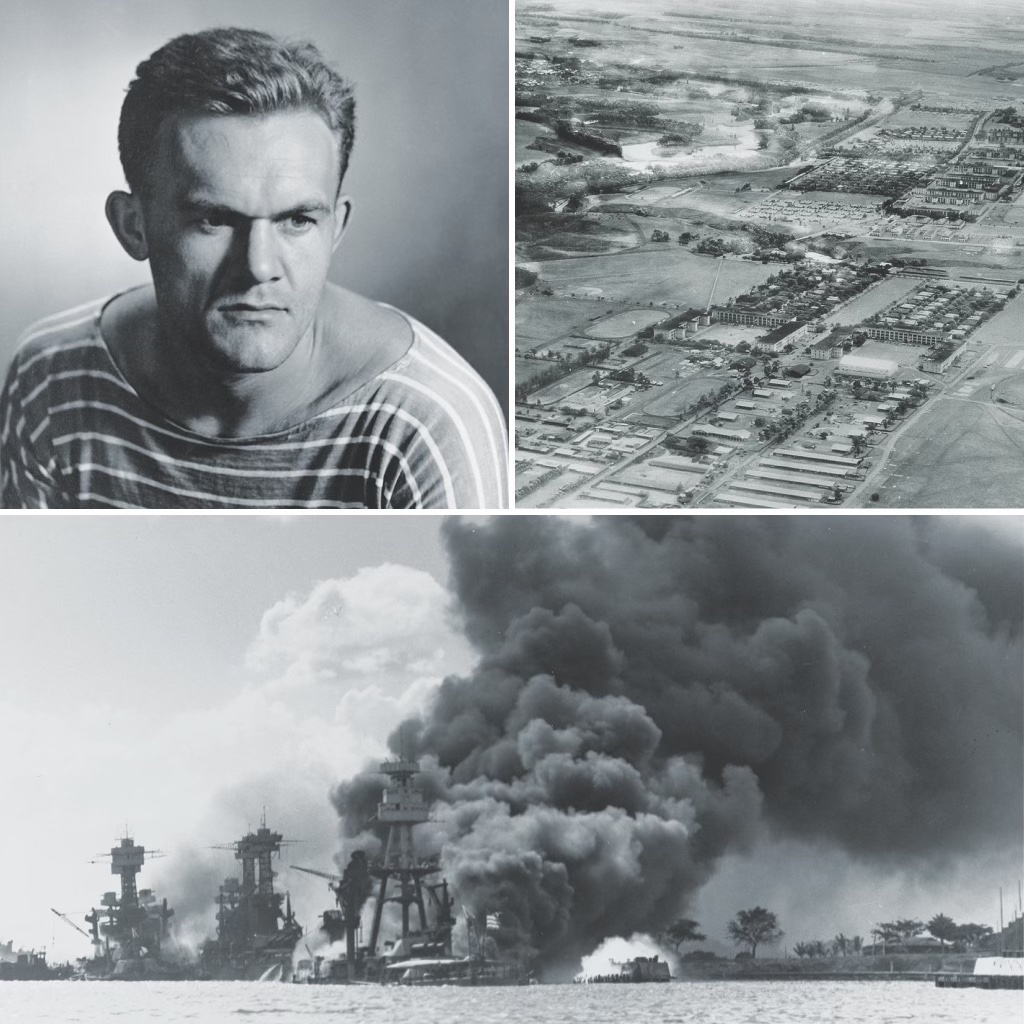

On the morning of December 7, 1941, Private James Jones was enjoying a quiet Sunday breakfast in the mess hall at Schofield Barracks, 25 miles inland from the silvery beaches of Honolulu, Hawaii. Jones had enlisted in the U.S. Army almost exactly two years earlier from his hometown of Robinson, Illinois. Although weak-eyed and undersized, Jones had readily adapted to life in the Regular Army and was now serving as assistant clerk for Company F, 27th Infantry Regiment, 25th Infantry Division. He was on 24-hour guard duty that day, two hours on and four hours off, but his official status as an orderly had permitted him to continue bunking in the company barracks rather than sleep in the cramped, crowded guard house. It would prove to be a lifesaving arrangement.

Jones had just polished off two fried eggs and an extra half-pint of milk when a series of dull explosions resounded from the direction of Wheeler Army Airfield, two miles away. An old-timer at Jones’s table looked up from his pancakes. “They doing some blasting?”

As the explosions intensified, seeming to draw nearer, Jones and others rushed outside to see what was going on. Pressed against a barracks wall and still absentmindedly clutching his bottle of milk, Jones watched in disbelief as a Japanese fighter plane roared by, its machine guns stitching a deadly crossfire down the dusty street. Jones could see the pilot clearly, waving and grinning as he passed. “I shall never forget his face behind the goggles,” Jones remembered decades later. “A white scarf streamed out behind his neck and he wore a white ribbon around his helmet just above the goggles, with a red spot in the center of his forehead.” Three of Jones’s friends were killed in their beds when another Japanese fighter strafed the guardhouse where Jones might have been sleeping as well.

In the developing chaos, Jones rushed to headquarters, where he was put to work running messages between overwrought officers. Later that day the entire contingent at Schofield Barracks headed out for the various beaches on Oahu, where Japanese invaders were expected to attempt a landing at any time. Riding in a convoy of camouflaged trucks from the inland plateau down to where the barracks stood, Jones could see ugly columns of black smoke billowing into the clear blue sky above Pearl Harbor. The bookish history buff, who had just turned 20 and aspired to be a writer someday, struggled to put the onrushing events into perspective. “I remember thinking with a sense of profoundest awe that none of our lives would ever be the same,” he would later write. “A social, even a cultural watershed had been crossed which we could never go back over, and I wondered how many of us would survive to see the end results.”

The caravan wound its way south-southeast, dropping off truckloads of soldiers every 10 miles or so in an arc above and below Waikiki. Jones’s unit established a mobile command post midway between Wailupe and Hanauma Bay on the extreme south end of the island. The men were armed with nothing but their rifles and the machine guns mounted on top of each of their trucks. Behind them lay the smoldering ruins of the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor. In less than two hours, Japanese warplanes had sunk two American battleships—Arizona and Oklahoma—and badly damaged seven others, along with a dozen smaller vessels and 300 airplanes. More than 2,400 soldiers, sailors, and civilians were killed in the attack; another 1,000 were wounded. Fortunately for the United States, all of the Pacific Fleet’s vital aircraft carriers were out to sea at the time. Unaccountably, the Japanese didn’t hit the base’s oil storage depots, repair shops, shipyards, and submarine docks. The navy quickly rebounded from the attack, but more than two years after World War II had begun in Europe, it had arrived without warning on America’s doorstep.

Jones and his fellow soldiers fully expected to be attacked within days, perhaps even hours. Jones’s group bivouacked on the beach at Wailupe beside a weekend home owned by Harry Arnold, a Honolulu physician. Soldiers stretched barbed wire along the beach between machine-gun emplacements. Jones prepared the company’s daily report and roll call and helped the first sergeant distribute food and supplies to troops patrolling the coast. As the days went by, the fear of imminent invasion diminished, and Jones spent much of his off time with Dr. Arnold and his family. One night he gave Mrs. Arnold a handful of poems he had written at Schofield Barracks. “Hang on to these,” he told her. “I’m going to be famous one day.”

It would take Jones a full decade to make good that boast, with the writing and publication of his first novel, From Here to Eternity, in the autumn of 1951. The doorstop of a book drew on Jones’s two years at Schofield Barracks, culminating with the attack on Pearl Harbor. It was a valedictory account of the final days of the Regular Army, before America’s entry into World War II brought millions of draftees and volunteers pouring into the service. Like many first novels, it was partly autobiographical, and Jones also incorporated details about many of his fellow soldiers. Jones wanted it to be a ground-level view of the army—from the perspective of the common soldier, not the great generals or the famous battles. As he would explain to Maxwell Perkins, his renowned editor at Scribner’s, “I have always wanted to do a novel of the peacetime army, something I don’t remember having seen.” It would depict, he said, “the small man standing on the edge of the ocean shaking his fist.”

Jones had done a fair amount of fist shaking himself. As the younger son of an alcoholic dentist and a faded society matron in southeastern Illinois, he had grown up in a poor but genteel family, largely ignored if not indeed unloved by his distracted parents. Except for English, he did badly in school as well as on the athletic fields. He was short and unattractive, with a prominent chin and large ears that stuck out “like a car coming down the street with both doors open,” as his father said unkindly. He nursed plans to run away from home and join the French Foreign Legion. Meanwhile he lashed out, having numerous fistfights at school and once pushing another boy through a plate-glass window. On his father’s advice, he enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps in November 1939, three days after his 18th birthday.

After basic training at Chanute Field, Illinois, and Fort Slocum, New York, Jones sailed with his unit to Hawaii, arriving on the island of Oahu in early February 1940. At Hickam Field, adjacent to the massive naval port at Pearl Harbor, he was part of the 17th Army Air Corps. His weak eyesight disqualified him from pilot training, and he declined to attend mechanics school on the grounds that he was not mechanically inclined. Much to his disgust, he was assigned to clerical school. “I didn’t join the army to be a clerk,” he complained to his brother, Jeff. He soon transferred to the 27th Infantry Regiment at Schofield Barracks, though he would have to undergo basic training again as a foot soldier. He moved into Quad D, the home of F Company, one of eight three-story stone barracks arrayed around the dusty parade ground known as Sills Field. He earned $21 a month.

Army life at Schofield Barracks was literally regimented: reveille at 6 a.m., roll call at 6:30, then breakfast, barracks detail, and uniform inspection, calisthenics at 9, infantry drill, 11:30 mail call, noontime lunch, afternoon work duties, 5 p.m. retreat, and the ceremonial lowering of the flag. Evenings were free, and Jones and his comrades hung around base or went into the neighboring village of Waliwa to drink and roister. They made few trips into Honolulu, since the bars there were too expensive for humble enlisted men. Schofield emphasized intramural sports, with each company fielding football, baseball, basketball, track, boxing, and softball teams. During Jones’s time at Schofield, his company won three regimental championships. Athletic mediocrity notwithstanding, he gamely took part in boxing and football, seriously hurting his ankle playing the latter—an injury that would continue to plague him for several months.

Despite his transfer to the infantry, Jones found himself doing clerical work again as an assistant company clerk. “About all I do,” he told his brother, “is type orders and letters and run messages.” He worked directly under the new company commander, Captain William Blatt, a fellow Illinoisan and Northwestern University graduate who encouraged Jones’s early writing efforts. Jones’s duties also brought him into daily contact with the company’s first sergeant, communications specialist, and bugler, all of whom would appear in From Here to Eternity. He used the office typewriter for his own writing when off duty and carried a small notebook with him to jot down his thoughts, impressions, and observations. One day when he was at lunch, a jokester posted a handmade sign on Jones’s desk: genius at work. Jones took the joke good-naturedly, leaving the sign in place.

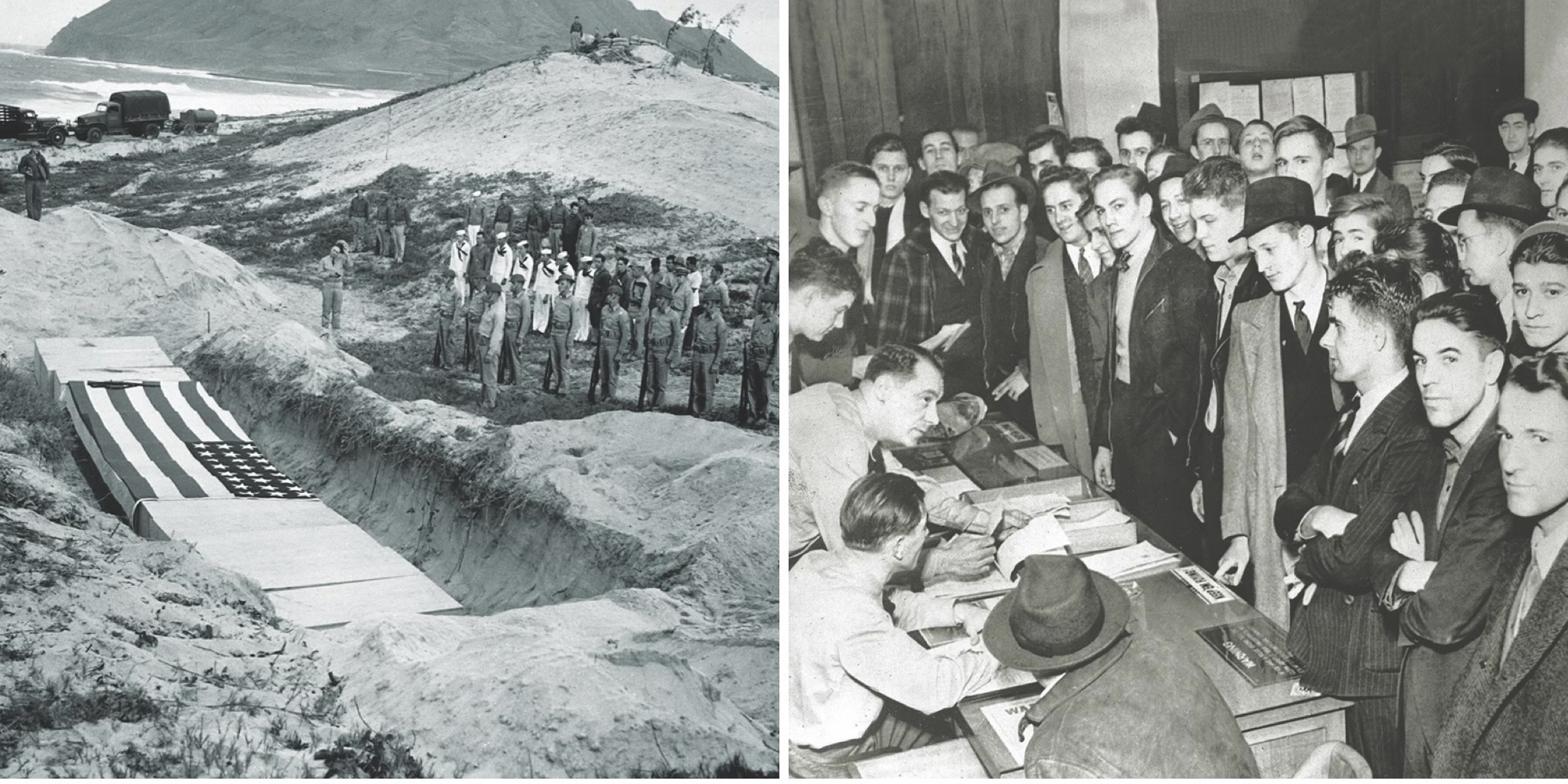

As war worsened in Europe and the Far East in 1940 and 1941, the Regular Army swelled from 300,000 men to more than a million. The dramatic expansion was fueled by the Selective Service Act of 1940, which drafted soldiers into the armed forces with increasing urgency. The U.S. Army’s Hawaiian Division, of which Jones’s 27th Regiment was a part, was expanded to create two units, the 24th and 25th Infantry Divisions. Jones was assigned to the 25th, nicknamed Tropic Lightning, whose members wore a shoulder patch of a Hawaiian taro leaf superimposed with a yellow lightning bolt.

In the spring of 1942 Jones received permission from Blatt to enroll in part-time English classes at the University of Hawaii in the hills above Waikiki. The would-be writer worked hard on his sketches, short stories, and poems. His professors and fellow students encouraged Jones, who divided his time between campus and the base. This idyllic lifestyle, however, came to an end in September 1942, when the 25th Division went on high alert. Jones and his comrades began a crash course in advanced infantry training—jumping off barges, wading ashore, firing antiquated rifles, and crawling through mud and sand while carefully calibrated machine-gun fire zipped above their heads. “Our training was neither intensive nor complete; it was woefully inadequate, and we knew it,” Jones would remember. “But then these were the early days of the war. And perhaps it was really impossible to train a man for combat without putting him actually in it.”

Actual combat would come quickly enough for Jones and his comrades. On December 6, 1942, the 25th Division sailed from Hawaii aboard three naval troop convoys. Three weeks later the ships arrived off the coast of an unimpressive little island in the Solomons chain that none of the men had ever heard of: Guadalcanal. The division hurried inland to join a massive ground attack on the remaining Japanese positions north of Henderson Airfield in the middle of the island. The 1st and 2nd Marine Corps Divisions, supported by army troops from the 161st and 182nd Divisions, had cleared the airfield and driven the enemy steadily northward in five months of brutal, murderous combat. Now it was the 25th Division’s turn.

On his third day of combat, at the base of Sims Ridge near Hill 53, Jones was struck in the head by a piece of shrapnel. As he later recalled:

I thought I could vaguely remember somebody yelling. I blacked out for several seconds, and had a dim impression of someone stumbling to his feet with his hands to his face. It wasn’t me. Then I came to myself several yards down the slope, bleeding like a stuck pig and blood running all over my face.

Luckily for Jones, it was only a flesh wound. “As soon as I found I wasn’t dead or dying, I was pleased to get out of there as fast as I could,” he wrote. “It really wasn’t so bad, and hadn’t hurt at all.” He went to the rear to be treated, glad to escape further combat that day.

Jones rejoined his unit 10 days later, a bandage wrapped around his head and covering an eye. He was put to work disinterring and reburying American corpses from temporary graves. It was horrific work. Another day he went into the jungle to relieve himself and was attacked by a maddened, bayonet-wielding Japanese soldier who suddenly appeared out of nowhere. Jones managed to tackle the man, beat him unconscious with his fists, and stab him in the chest with the man’s own bayonet before smashing in his head with a rifle butt. The deadly hand-to-hand combat literally sickened Jones, who bent over and vomited. Searching the dead man’s pockets, he discovered a wallet containing two snapshots of the soldier posing with his wife and child. He vowed never to kill again.

Jones’s lingering ankle injury proved to be his golden ticket out of the war. Although he always wrapped the ankle tightly in yards of elastic bandages, it continued to pop out of place. Finally, after he collapsed abruptly while walking alongside his first sergeant, Frank Wendson, the noncom sent him to the rear. A surgeon examined Jones at the divisional hospital and declared him physically unfit for further infantry duty. “He looked at me and grinned,” Jones recalled. “I grinned back. If he could only have known how I was hanging on his every word and expression. But perhaps he did.”

Jones was evacuated to Auckland, New Zealand, where he endured a grueling three-hour operation, the last 20 minutes spent in agony after the anesthetics wore off early. He returned to the States in May 1943 and was sent to Kennedy General Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, to recuperate. For Jones, living among hundreds of grievously damaged men, including many multiple amputees, paralyzed and blinded soldiers, and psychologically traumatized shock victims, was emotionally grueling. “Men there did not laugh and smile about their wounds,” he wrote, “as they always seemed to do in the pictures in Yank and the civilian magazines.” Jones would unflinchingly recount his hospital experiences in Whistle, the third novel of his World War II trilogy, published a year after his death in 1977. (The Thin Red Line, about his combat experiences at Guadalcanal, was published in 1962.)

Jones would enjoy a long and lucrative writing career, but it is his first novel, From Here to Eternity, detailing his prewar experiences in the Regular Army in Hawaii, for which he is best remembered today. Such real-life comrades as Private Robert Stewart, First Sergeant Frank Wendson, Sergeant William “Chubby” Curran, Private Joseph A. Maggio, and Captains Thomas Griffin and William Blatt appeared in the novel, thinly disguised as Private Robert E. Lee Prewitt, First Sergeant Milton Warden, Sergeant James “Fatso” Judson, Private Angelo Maggio, and Captain Dana “Dynamite” Holmes. From Here to Eternity, both as a number-one best-selling novel and a multiple Academy Award–winning motion picture, endures as one of the frankest depictions of American life on the cusp of World War II, when, as Jones himself realized that smoke-blackened morning at Pearl Harbor, “none of our lives would ever be the same.” MHQ

Roy Morris Jr., a regular contributor to MHQ, is the author of nine books, including, most recently, Gertrude Stein Has Arrived: The Homecoming of a Literary Legend (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019). He received a 2020 Army Historical Foundation Distinguished Writing Award for his profile of World War II correspondent Ernie Pyle in the Autumn 2020 issue of MHQ.