At the peak of her long career, diminutive powerhouse Martha Matilda Harper was overseeing some 500 hair salons around the country, in Canada, and across Europe that promoted her Harper hair care method.

An impoverished child indentured in Ontario, Canada, she matured into a pioneering businesswoman in Rochester, New York. Though not the first American woman to make her fortune in hair care, Harper created one of the earliest business franchises in the United States, along the way enlarging opportunities for women to take charge of their economic lives.

She built an empire that blossomed, then languished forgotten until 2000, when Rochester resident Jane Plitt published Martha Matilda Harper and the American Dream: How One Woman Changed the Face of Modern Business. In her book, Plitt chronicled in detail how Harper founded one of the first commercial hair salons for women, created the reclining salon chair, managed a thriving business for decades, and found inspiration in the new religion of Christian Science.

Born in 1857, Harper was the fourth child of a self-centered tailor in a village outside Oakville, Ontario. She was seven when her father hired her out to relatives living 60 miles away, and at 12 she went to work for a local doctor who had his own line of hair tonic. The girl spent nearly a decade in his household and in 1882, not long after his death, left Canada for Rochester, New York, taking along her late employer’s hair tonic formula.

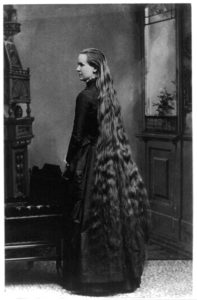

In Rochester she worked in the home of an elderly couple. In 1887 she began producing and marketing the tonic. Encouraged by the couple, who remained her support system for decades, Harper in 1888 opened a salon specializing in women’s hair and skin care, the front window bearing a picture of Harper and her floor-length tresses. As a logo she trademarked the horn of plenty. She patented her product, Mascaro Hair Tonique.

Sickened by exhaustion and pressure, Harper recovered thanks to treatment by a Christian Science practitioner. She never forgot those curative ministrations.

Prior to Harper’s innovations, most women had their hair done at home. Harper cultivated affluent customers, opening her first shop in a grand building that was owned by Rochester bigwig Daniel Powers. Persistence won her a month-to-month lease and access to well-heeled clients.

Fortune favored her location when a music studio opened next door; she offered her lobby as a waiting room for women accompanying children taking music lessons.

She made cleanliness and exemplary service Harper hallmarks. Noting the annoyance customers experienced when wash water ran down their necks, she devised a salon chair that reclined to suspend an occupant’s head over a complementarily shaped marble sink.

To polish her affect and make up for a lack of schooling she took night classes at the nearby University of Rochester. Her motto reflects her servant’s background: “Be equal to any problem that arises. Never give up. Be the master.”

Harper had forebears and role models. Madame C.J. Walker, a famous contemporary, was born enslaved as Sarah Breedlove. Walker over the years outlasted several husbands as she was establishing a hair care product line—and sales force—so successful that her operation came to include banking and insurance. In 1919 Walker was recognized as the first Black female millionaire.

Other women managed businesses ranging from steel mills to almond orchards. Some inherited enterprises or wealth, such as department store founders I. Magnin and Lane Bryant. Some ran taverns, mills, millinery shops, and other concerns with their husbands, the couples working jointly.

However, Harper, Walker, and a few others fit a different category: women who founded, expanded, and oversaw enterprises without significant involvement by a male partner or relative. These female entrepreneurs may have stood tall but their achievements stand overshadowed by the record of women as paid and unpaid workers and attention paid the lives of prominent women activists and writers.

Diverging from other business pioneers’ paths, Harper reached beyond goods and services. She created not only a public commercial institution for women, but economic opportunities for Harperites—female salon owners and operators the founder trained to establish their own Harper Method salons, adopt and replicate her techniques, and sell her products.

Unlike subsequent cosmetics magnates such as Helena Rubenstein and Elizabeth Arden, Harper promoted health and well-being, not cosmetics and beauty. Her salons did not offer permanents or hair dyes, but hair and skin care, including scalp, facial, and shoulder massage.

She offered evening hours, flexible work schedules, and childcare. Harper was in the business of serving and promoting women. She granted the first 100 salon franchises she licensed to working-class women.

Harper carved her particular niche. The pioneer of franchising in America is said to have been Benjamin Franklin, who licensed franchisees to reproduce his popular Poor Richard’s Almanac. Other franchisers were sewing machine inventor Isaac Singer and mechanical reaper inventor Cyrus McCormick, who had deals with salesmen to distribute their products.

Harper’s model stood apart from antecedents: she not only closely supervised the operation of Harper Method salons, but her contracts incorporated such niceties for franchise holders as group insurance, intense and ongoing training, a regular newsletter, and annual meetings.

The first woman to be inducted into the Rochester Chamber of Commerce, she was still running her franchise business in her 80s. Her husband, whom she married at 63, took over the business after her death in 1950.

He failed to sustain the sense of personal mission Harper instilled in franchisees. Ultimately the business was bought. It folded in the 1970s.

In explaining how a woman less than five feet tall from unremarkable origins developed an innovative business model, biographer Plitt highlights the role of place: Rochester, a boomtown home to women of means and a hotbed of activism, provided a strong customer base.

Suffragist and local Susan B. Anthony was a patron and friend. More fundamental inspiration likely came courtesy of Christian Science. Founded in 1879 by Mary Baker Eddy in Boston, Massachusetts, the sect not only stressed the power of belief and prayer as a means of managing life and its setbacks, but also promoted equality of the sexes as an aspect of the deity.

As Harper had, Eddy overcame illness and many obstacles, and her credo stressed health of both mind and body. Besides a key to well-being, Christian Science offered a horizontal organizing principle that may have influenced Harper’s vision for her far-flung salon network.

Eddy’s writings were the religion’s mainstay, but satellite churches had no clerical leaders. Instead, congregants delivered Eddy’s readings. In effect, these satellites functioned as branch offices, and may have provided a blueprint for Harper’s salon franchise arrangement.

Eddy did not pronounce herself a feminist or suffragist, and neither did Harper. But each affirmed her autonomy in the institutions they founded and managed over the courses of their lives. According to Plitt, Harper’s manual stated: “[W]e are helping women attain the best that life has to offer—self expression.”