The much-publicized 1883 matches between rival sharpshooters Capt. A.H. Bogardus and William F. “Doc” Carver cemented exhibition shooting as a popular American spectator sport, thus it was only a matter of time before a female counterpart broke into the game. At first a curiosity, Annie Oakley came to outshine all comers in skill and theatrics, outdrawing even the men in ticket sales. Her success occasioned throngs of prospective young female emulators. Unlike most, Freeda Hartzell of Chadron, Neb., held a distinct advantage.

The adopted daughter of James Orlin and Mary (née Boruff) Hartzell, Freeda was born in Omaha on Dec. 20, 1891, and spent her early childhood on the family homestead east of Chadron, the Dawes County seat. A shopkeeper and self-styled cowboy, Jim Hartzell had performed in and managed various Wild West shows, and he brought up his daughter in the entertainment world. Two years after Freeda’s birth he helped organize and promote the Great Cowboy Race from Chadron to Chicago. On the evening of June 13, 1893, Hartzell, in his capacity as a race committee member and chief of the local volunteer fire department, signaled the start of the contest with a shot from the gold-plated, ivory-gripped revolver Colt had put up as a prize. The spent cartridge case became a family heirloom.

From age 5 little Freeda traveled the show circuit with her vagabond parents, receiving private tutoring while on the road. She also benefited from her father’s shooting instruction. With practice and experience, the girl soon made her trick-

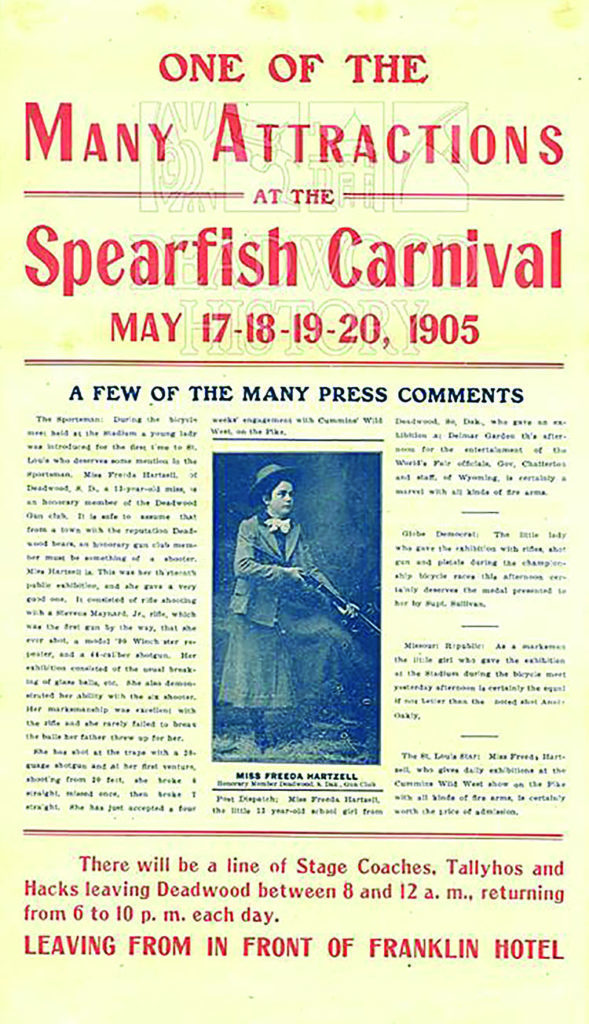

shooting debut, and by age 11 she’d blossomed into a center stage solo act. When the family settled for a time in Deadwood, S.D., the town embraced and promoted Freeda, publishing her show dates in the local papers and later making her an honorary member of the gun club.

Among the performers in Colonel Frederick T. Cummins’ Wild West Indian Congress between 1903 and ’05 was little Miss Hartzell, billed—as were many of her peers—as the “Champion Rifle Shot of the World.” In 1904 she shared the playbill at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis with Will Rogers, who was polishing up the trick roping part of his vaudeville act. The August 6 Minneapolis Journal provided a tease of her routine: “Miss Freeda Hartzell, age 13, a prodigy from South Dakota is astonishing spectators.…She uses .38- and .45-caliber revolvers, five different rifles and two shotguns. She shoots small coins thrown into the air…and performs other interesting and difficult feats in fancy shooting.” When Cummins played Chicago’s White City Amusement Park the following year, the show featured a procession of Indian chiefs from 51 tribes, a re-enactment of Custer’s Last Stand and a trick-shooting exhibition by Miss Hartzell, still the reigning “Champion Rifle Shot of the World.”

Freeda and rivals shared an understandably common and limited bag of tricks. All could pluck from the air three or four wood blocks tossed at once, for example, and a tin can remained airborne long enough for each to riddle it with five rifle shots. Those who couldn’t weeded themselves out in short order. Showmanship, though, varied in degree. Jim Hartzell recognized its importance, as did his daughter.

Freeda and family spent much of the first decade of the 20th century engaged in this nomadic pursuit. The heyday of the Wild West show was on the wane, however. Seeing the handwriting on the wall, the Hartzells returned to their Nebraska farm.

One of Freeda’s final public appearances came in mid-September 1909 at the Dawes County Fair in Chadron. The assembly that year was particularly impressive. Seven hundred traditionally garbed Sioux from the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, just across the border in South Dakota, camped on the fairgrounds and participated in the festivities. Also present were four troops of U.S. cavalrymen and the post band from Fort Robinson, down near Crawford. Many of the county’s 8,200 residents attended the four-day affair, which provided local cowboys and cowgirls a chance to show off. There were bucking contests and other mounted events, and the Chadron Gun Club held a match at their facility. But the greatest attraction proved to be the fancy shooting exhibition Miss Hartzell put on Saturday afternoon the 18th.

The appeal of the Wild West show had about run its course, and with it the demand for female trick shooters. Seeking to remain in the public eye, Freeda sent a publicity image to Outdoor Life, hoping for a kind word or two. Editor John A. McGuire obligingly ran her photo and a blurb in the November 1910 issue. Six months later, on June 26, 1911, 19-year-old Freeda Hartzell married Chicago & North Western Railroad freight conductor Guy Romine. Settling in Chadron, the couple operated a successful car garage/repair shop and soon had a daughter.

But Freeda Hartzell Romine wasn’t done with the spotlight. In 1915 she played the female lead in the silent Western Wild Bill and Calamity Jane in the Days of ’75 and ’76, filmed in Deadwood and the cattle country west of Chadron. Local talent A.L. Johnson played Wild Bill Hickok, while Freeda’s mother wrote the screenplay and played Calamity’s beleaguered mother. Mary Hartzell made no attempt to pen a fact-based narrative. Among other howlers, Wild Bill vies with Jack McCall (Hickok’s real-life assassin) for Jane’s affections. In the climactic scene rifle-toting “red men” chase down a gold-encumbered stagecoach. Riding to the rescue are Fort Robinson troopers in period costume, who play opposite warbonneted Sioux extras from Pine Ridge. The seven-reel, 70-minute movie briefly made the rounds in local theaters before time and disinterest relegated it to the Nebraska state archives in Lincoln.

Freeda and Guy Romine divorced in 1930. Ten years later she moved to Indianapolis to be close to daughter Kathryn, and for the next 24 years she remained in Indiana, sustaining herself as a drugstore clerk. In 1961 Freeda returned to Chadron for a visit, an occasion meriting statewide mention in newspapers under the headline Crack Shot. Freeda Hartzell Romine, among the last of the Wild West show performers, died with her boots off at age 72 on Oct. 30, 1964.

This story was written by Jim Foral, and was published in the April 2020 issue of Wild West.